“I Never Cared About Normalcy.”

Three Things To Enjoy in Relation to This Book:

A large cup of Tim Hortons coffee

Hostess Donettes

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine, by Gail Honeyman

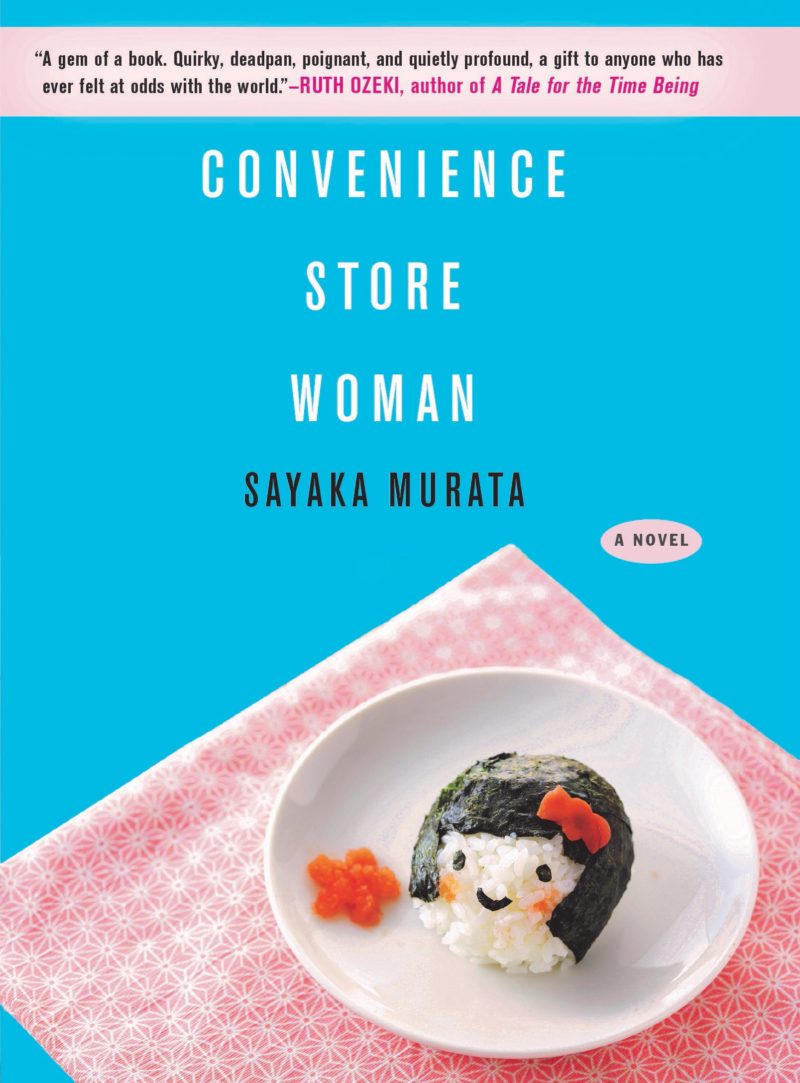

For this series, I ask writers I admire to recommend a book. I read it, then we talk about it. For this installment, Lauren Wilkinson recommended Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata.

Lauren Wilkinson’s novel American Spy is a gripping, heart-felt debut that, yes, is about a spy, and, yes, did make me cry. Aside from the pitch-perfect writing, what impressed me most was Wilkinson’s ability to combine a completely entertaining genre yarn with an unflinching examination of race, gender, motherhood, the walls we must build to protect ourselves, and how those effect the ways in which we’re able to love.

Convenience Store Woman is a very different kind of story. It’s a short novel about a woman who feels most at home while at work, and in our discussion of it, Wilkinson and I touched on questions of normalcy, routine, John Cusack, and the underlying violence in human nature.

—Colin Winnette

THE BELIEVER: Do you mind providing a brief description of Convenience Store Woman, to ground those unfamiliar with it?

LAUREN WILKINSON: Convenience Store Woman is a Japanese novella in translation about Keiko Furukura, a woman who feels like the only place she fits in is the convenience store in which she works. I’d say that the book has a playful tone that is occasionally undercut by something a bit darker.

BLVR: What brought this book into your life? What caused you to pick it up for the first time, and what was that experience like?

LW: The author, Sayaka Murata, gave a reading at the McNally Jackson bookstore in Brooklyn, which was organized by her publisher and the Japan Society. I hadn’t even heard of the book until I showed up to the event, so it was all one big lucky coincidence. I read it in one sitting, on a plane coming back from Paris. This was around the holidays, so before Paris I’d been in London visiting family.

This book stayed with me because it a strange and slightly unruly little book. And yet, not only is it allowed to be that, it seems like it’s loved for all its weirdness. Apparently, it’s a bestseller in Japan. It won the Akutagawa Prize. I have not taught it, but I do recommend it to friends because it’s short and insightful. And fun.

BLVR: The novel opens and closes with moments describing the “sounds of the convenience store,” not the sights or smells of the place. In fact, smell felt conspicuously absent to me. What sets sound apart from the other senses here?

LW: The book’s translator, Ginny Tapley Takemori also spoke at the reading, and she pointed to this passage when the conversation turned to some of the difficulties that came up while translating it. The Japanese convenience store is apparently so ubiquitous and such a fundamental part of daily life that even with a very limited description, a Japanese reader could immediately picture the space in a way that an American reader would not be able to do. So that idea is what stood out for me most: what I might take for granted as a writer because I assume the reader and I share a cultural context. My own book was just translated into Italian and I was surprised by the things that the translator (who is excellent) bumped up against. They were almost always things that I thought of as throwaways. Things that were mundane, turns of phrase that I didn’t even really think about as I reached for them when I was writing.

BLVR: What’s an example of something your translator bumped up against?

LW: She bumped against the phrase “the fall.” I meant autumn and she thought so, but checked in to make sure that I didn’t mean something more grandiose and metaphorical. She’s an amazingly thorough translator. She also pointed out a few of the factual errors I made.

BLVR: The narrator describes guidelines for being a “normal person,” as provided her by life at the convenience store. More specifically, she reads the store’s employee manual in this way. I related, and it got me thinking about the arbitrary objects or experiences one can fixate on because on they seem to reveal to us some lesson about how to live. Did you have a “manual” like this at some point in your life? I remember being in middle school and feeling like certain John Cusack movies could teach me how to be a good man.

LW: I never really experienced that particular anxiety—wanting to be a normal person. If I wanted anything when I was a kid it was to be cool. And I think I’m more inclined to turn to the people in my life for instruction rather than books or movies, so it’s hard for me to think of a manual. That said, I did love Harriet the Spy and Ramona Quimby and the Blossom kids from The Not-Just-Anybody Family by Betsy Byars—all of them being smart, plucky outsiders. So those must’ve been characteristics that admired when I was a child.

BLVR: The narrator often talks about how different she is from everyone else. She describes herself as, “needing to be cured.” I fluctuated between thinking this was self-imposed, something only she could see, and feeling like it was reinforced, or even asserted, by external forces. Maybe it’s both, or maybe it’s neither. But I was curious, in your reading, what sets the narrator apart from everyone else, if anything?

LW: I think it’s a question of self-perception, which is why she’s so relatable. Everyone has wondered if they’re normal or not because that’s how normalcy is set-up. It’s not some objective characteristic that can be measured—normalcy is a slippery idea that shifts around all the time because it’s predicated on different social contexts. I mean, isn’t it? I’ve probably always thought that on some level even if I wouldn’t have articulated it in precisely this way. But that’s what I said that I don’t really remember being hung up on normalcy as a kid/teenager. I liked rules, I was occasionally prim (the rules of etiquette spoke to me), and I generally responded well to authority figures, but I never cared about normalcy. It has always struck me as being an unattainable standard.

BLVR: I totally agree. Unattainable, and yet so frequently referenced. I’m not sure I ever wanted to be normal, but I wanted to understand what it meant when people would ask me, “Why can’t you be normal?” I wanted to be cool too, but “cool” always struck me as a byproduct of a certain kind of commitment, not an accident. I felt like I couldn’t be “cool” if I didn’t know what I was committing to, or committing to rejecting. Which is another way I related to the narrator here. It’s like she’s doing research on normal. Rather than being normal, she’s building a life that signals “normalcy,” or addresses it in some way. A big of part of her ability to accomplish that comes from structured behavior. Doing her best to understand, and respond to, societal expectations.

LW: I think Murata is getting at something important about the relationship between routine and normalcy: that routine is really what we think of when we think of “normalcy.” Which is part of the reason that in the darkest periods of human history, people aren’t always so quick to revolt. If a power structure can offer a sense of routine alongside brutal oppression, people seem unnervingly quick to forgive the latter if they feel soothed by the former.

BLVR: There’s a dark charm to the book. Especially in the opening, reading about the strange acts of violence perpetrated by the narrator. That violence disappears toward the end of the novel, once those routines are governing her daily life. Is there some implication here that beneath those basic guidelines toward civility or “normal” behavior, there are seething violent impulses? Or at the very least, the capacity for either exists in us, and therefore non-violence is a consciously performed act?

LW: Yes, I think that’s an excellent interpretation! Which is quite a chilling idea when you examine it.