I’d like to try taking this absolutely seriously. If I attempt to do that, I find myself asking, “What questions do I ask myself about my work and my life, and about the lives and behaviors of others?” Here are some of those questions; I often don’t have definitive answers.

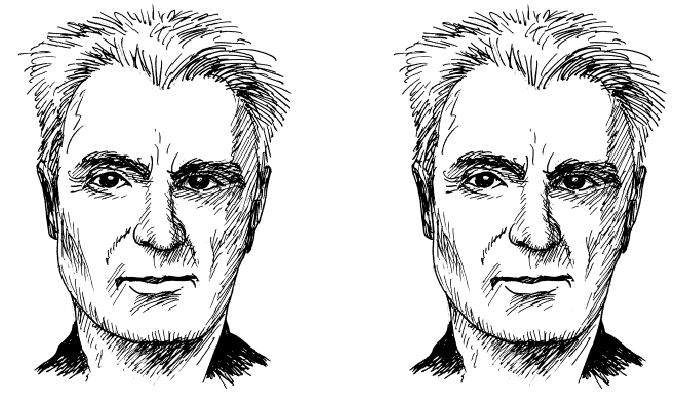

—David Byrne

DAVID BYRNE: David, do you think there are bad people? Do people knowingly do bad things?

DAVID BYRNE: It’s very hard for me to believe that people can knowingly do evil, be bad. I’d prefer to think that somehow people who do bad things honestly believe they are doing them for some greater good. Ends justify the means, in other words. Our capacity for self-deception is boundless, so this belief of mine has some basis in reality and experience. People—people I know and respect—believed strongly that invading Iraq was a good and necessary thing. These people were not Bush supporters, but somehow they convinced themselves this had to be done. They believed this even though there was no proof for any of the justifications being held up for invasion—there were no weapons of mass destruction, for example. I believe these people are essentially good people who let their emotions determine their decision-making as a consequence of 9/11. Many of these people have since recanted and admitted they were mistaken. So that experience agrees with my assumption.

Then, not too long ago, it came out that Nixon and Kissinger knew that the Vietnam War—the American War, as the Vietnamese call it—was unwinnable. They knew this, and yet they chose to continue the war, killing thousands more—many of them innocent civilians—so that Nixon might get reelected. According to my assumption, they must have convinced themselves that reelection, by any means necessary, would justify the lives lost. But this pushed my assumption a little too far; when I read that, it became hard to continue to believe that people are not knowingly evil. I would like to think that these men and others like them are the exception; that most of us, though we often deceive ourselves and others, or justify deceit if we think the ends are good enough, would not go as far as they did. Most of us, I believe, could not commit atrocities with no valid justification.

DB: David, you seem like a generally happy person. Where does happiness come from?

DB: I ask myself this fairly regularly. This morning on the way to the dentist of all places! Money can’t buy happiness, but without the basic necessities, it is indeed harder to be happy. But if we assume everyone could have enough to eat, a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in