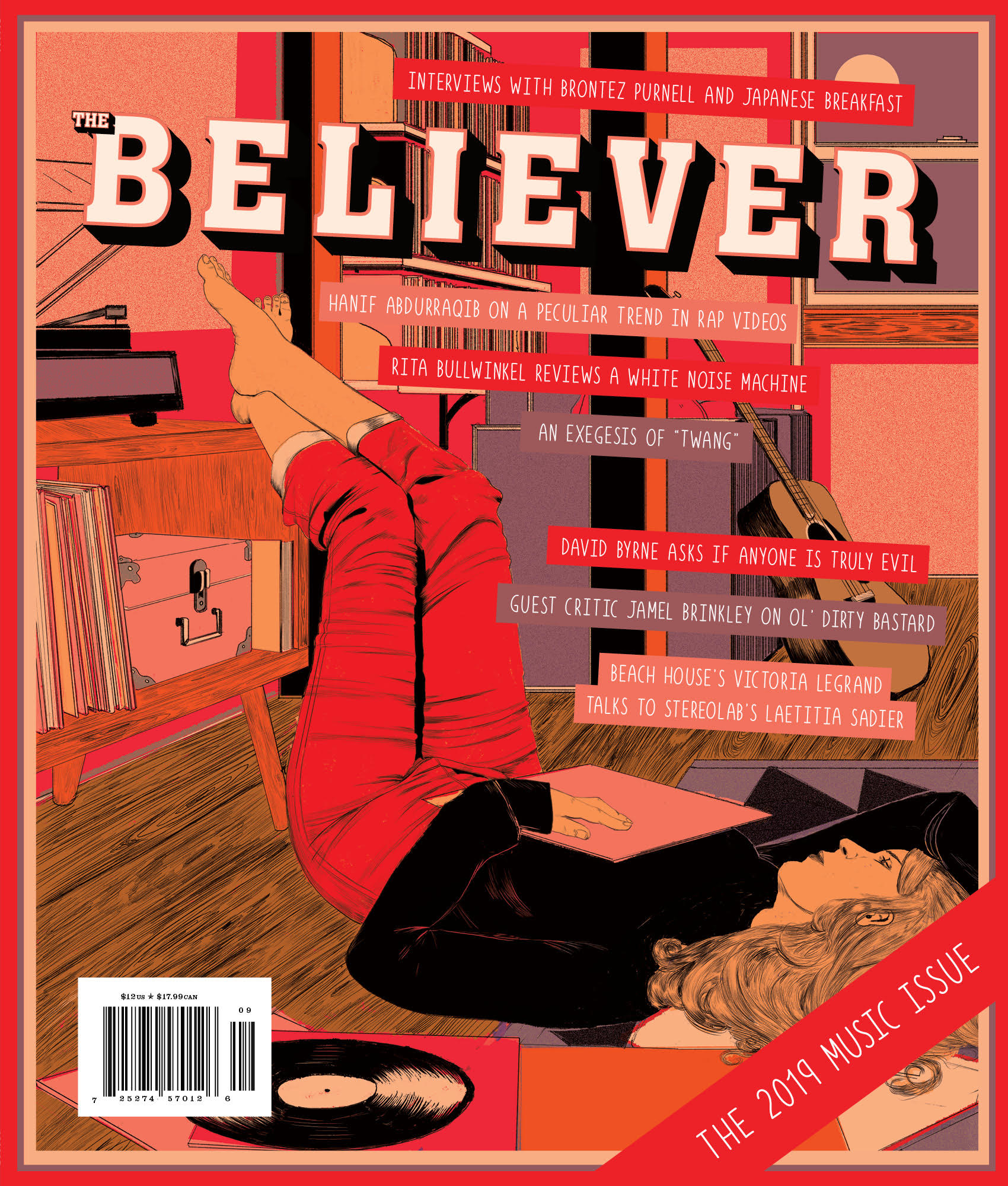

To celebrate the brand new redesign of The Believer, we offer to you conversations with contributors and artists from inside our 2019 music issue.

A few words with our cover artist, Nicole Rifkin:

Who: I’m an illustrator and cartoonist living in Brooklyn.

What: This illustration depicts what I would call a “perfect music moment,” when you play your favorite band and just let it soak in.

When: I worked on sketches in stages, and then finished it by staying up all night at the end of the process. I nearly failed color theory in college and was only passed because the professor did not want me in her class again, so I spent a really long time trying to get the right mood from the palette.

Where: I work in my home studio, which is essentially just our living room. I watched The Dirt while drawing it and that has to be one of the funniest things Netflix has ever produced. I demand a sequel.

Why: I believe so much in the bands I love and they help me stay creative, so I wanted to draw a picture for people like me.

Regarding the incidental illustrations:

“Music is so often a part of our identities and a way in which we set ourselves apart from others. This series applies that attitude to animals behaving uncharacteristically while listening to music. While the scenes I’ve drawn probably aren’t things you’d normally see, perhaps it’s not too far of a stretch of the imagination… I mean, I can definitely imagine a universe where vultures are into Pink Floyd.”

—Katherine Shapiro

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in