“Americans are people too, Jim.”

Challenges presented in adapting Beckett and Melville for the stage:

Who speaks?

Who is speaking?

Moby Dick is a long book.

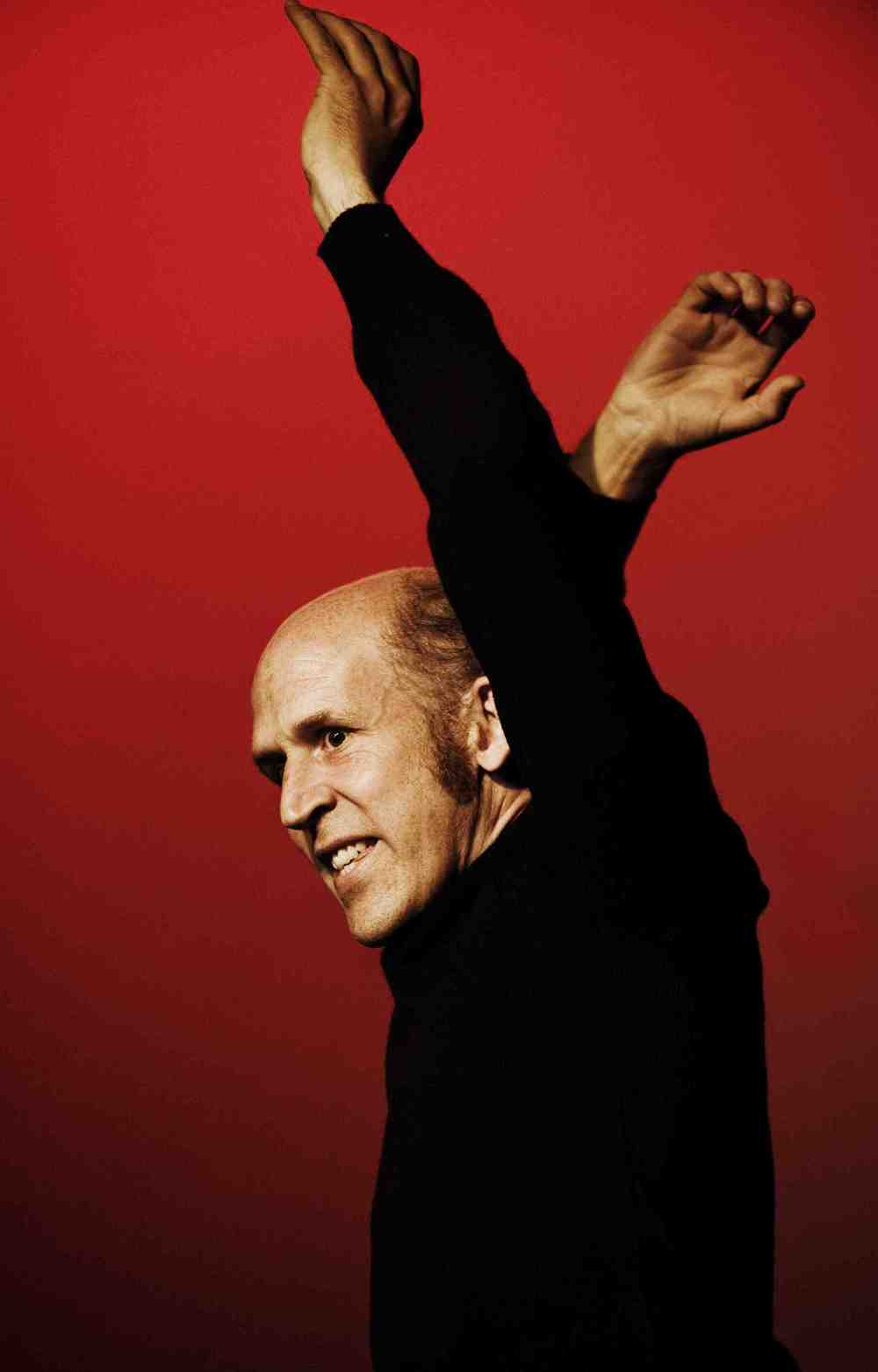

Husband and wife Conor Lovett and Judy Hegarty Lovett are the co-founders and co-artistic directors of the Gare St. Lazare Ireland theater troupe. Both were raised in Cork, Ireland, but settled in Paris twenty years ago. The repatriation may have been a sheer coincidence but makes perfect sense, as over those same two decades, Gare St. Lazare Ireland, with Judy as director and Conor principal actor, has earned an international reputation as our foremost interpreters of the work of fellow Parisian transplant Samuel Beckett. While their repertoire, not surprisingly, includes Waiting for Godot and other pieces Beckett wrote for the stage, it goes far beyond that.The New York Times dubbed the troupe“the unparalleled Beckett champions” for their adaptations of Beckett’s novels and short prose, from a three-hour production of his trilogy of novels (Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable) to their most recent project, a staged version of Beckett’s final novel, How It Is—a three-part novel, it’s worth noting, which was published with no punctuation.

In what might seem an unlikely turn amid all that Beckett, for the past ten years they’ve also been touring the world with a two-hour one-man adaptation of Moby Dick. During their annual visit to the States this autumn, with stops in Hudson, NY, Middlebury, VT and the University of Florida at Gainesville, Gare St. Lazare Ireland will be presenting Moby Dick, The Beckett Trilogy, and another new adaptation of one of Beckett’s later prose works, ill seen ill said, featuring actor Deb Gwinn, founder of the Vermont Coffee Company playhouse.

I spoke with the Lovetts via phone at their home in Paris, as they were preparing to head back to their home theater in Cork for the premiere of How It is (Part 2). We talked about the troupe’s origins, what it takes to transform Beckett’s novels into theater pieces, and just how the hell you make that mighty leap from Beckett to Melville.

—Jim Knipfel

I. “This is just the actor.”

THE BELIEVER: When was the troupe founded?

CONOR LOVETT: Our troupe, Gare St. Lazare Ireland, dates from approximately 1996, 1997.

BLVR: So you’ve been around about twenty-three years or so.

CL: That’s right, but we came out of an earlier incarnation called Gare St. Lazare Players. They originated in Chicago in the mid-eighties. There was a gentleman called Bob Meyer, who’s an artist, and he began doing theater plays...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in