“A lot of people find true crime relaxing—because it lets us off the hook: not only does it reaffirm that we’re safe, we’re not the ones who get hurt, but it also tells us we don’t need to do anything. If you say about these women, “Well, she was doomed, can’t you see the tragedy in her eyes?”—that completely lets us forget the fact that we, as a society, have often failed these women.”

Serial Killers are:

Not emotionally healthy

Promoted by the FBI as mythic, nightmare figures

In reality, often boring

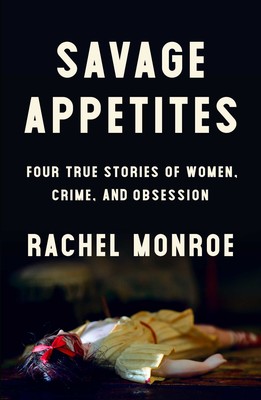

“Part of the curriculum of growing up as a girl,” Rachel Monroe writes,“is to learn lessons about your vulnerability—if not from your parents, then from a culture that’s fascinated by wounded women.” Out today from Scribner, Monroe’s Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime and Obsession is about what happens when these girls grow up.

Monroe is one of them. So am I. Millennials grew up in a media landscape saturated with stories of dead girls and “innocent victims”; the oldest millennials were just beginning to make sense of the world around us when the United States’ violent crime rate reached its all-time peak, in 1991. As we grew, we watched it shrink—unless we were watching the true crime media of the time. The 90s brought us Court TV, and in turn, Court TV brought many of us up. When I was six years old, I watched the O.J. Simpson trial alongside Sesame Street. About the only thing that seems as true now as it did then was the feeling that the grown-ups were not nearly as in control as they wanted us to believe.

True crime media is, allegedly, having “a moment.” (The genre has gone mainstream in more ways than one: the chart-topping podcasts that aren’t about missing and murdered white women are often about the crime saga—the longest, dishiest, most devastating of them all—playing out in the Oval Office.) The Internet has helped lone true crime obsessives realize that we aren’t alone at all. Today, amateur sleuths pool their insights in online communities dedicated to cracking cold cases, and fans of My Favorite Murder turn to the podcast not to ratchet up their anxiety about inhabiting this world, but to soothe it. It seems that, in a few short years, millennial women have transformed a solitary vice into a shared identity. But why?

None of this is exactly new: true crime has been with us for as long as narrative has. The first two stories in the Bible, following the creation of the Earth itself, are a noir—the snake always hisses twice—and a murder within the family: exactly the kind of crime that we might describe, a few thousand years later, as “unimaginable.”

“When we say unimaginable, of course,” author Sarah Viren writes, in an essay unspooling her own fascination with a woman guilty of killing her own children, “we don’t mean that we can’t imagine the act. We mean that we don’t want to imagine it.” The medium of true crime has fragmented and transformed—the paperback cocoon has busted open—but the stories we tell will remain the same, and will be of little use to us, until we use them to witness ourselves.

“The murder stories we tell, and the ways that we tell them, have a political and social impart and are worth taking seriously,” Rachel Monroe writes in Savage Appetites, a book dedicated to doing exactly that. Savage Appetites is a dense, delightful, troubling, and ultimately inspiring book that encourages us to contemplate our own dark places, and to wonder what truths may lie just beyond the stories we know by heart.

One afternoon in late July, I called Rachel Monroe at her sunny home in Marfa, Texas. We talked over the phone about Columbine, Sharon Tate, the victims’ rights movement, what it does to you to grow up consuming stories of your own potential victimhood.

—Sarah Marshall

I. Desire That Doesn’t Fit Into Our Framework

THE BELIEVER: I’d like to start talking about this book with the fact that the first thing I ever read of yours was your piece on Columbiners, on The Awl, in—was it 2013?

RACHEL MONROE: 2012.

BLVR: 2012! That was the first year I published anything online, and that was on The Hairpin.

RM: Me too! That was more or less the first thing that I ever published online. That might not be literally true, but it is emotionally true.

BLVR: “If it’s not literally true it’s emotionally true” is a key organizing principle of true crime.

RM: [Laughs] Totally.

BLVR: It feels as if that essay was a germinating seed and this book is the tree that grew from it. One of the things I really like about the life that essay has in this book now is that it’s contained within a larger piece that to some degree contradicts it.

RM: I ended up twisting around that Awl piece so much, and I still don’t feel like I have solid ground, exactly. But when I wrote it, I was feeling very protective of, and amused by, and kind of darkly charmed by the Columbiners. I definitely identified with them. I was writing it from that place—and probably projecting myself onto them, which I think is another recurring theme of this book, and of my thoughts: how we use these true crime stories to say things about ourselves, to claim emotional states or subject positions that we feel like we can’t otherwise claim with our own lives.

BLVR: What inspired you to write the Columbiner essay in the first place?

RM: It was right before I moved to Marfa. I was in Baltimore, and it was right before I moved, so I had already sold my bed on Craigslist, so I had a mattress on the floor in this disgusting warehouse I was living in, and was feeling very much like, “Oh no, what have I done? What am I doing with my life? Why am I moving to rural Texas?” There’s something about sleeping on the floor. Without a bed. That was something else I realized, in the course of writing the book—that these states of really wanting to go into somebody else’s trouble often coincided with moments in my own life when I felt myself adjacent to trouble.

There was a school shooting that day just north of Baltimore. A kid named Bobby Gladden. And I’m not finished packing, but I immediately need to know everything about Bobby Gladden. Somehow that felt incredibly urgent and relevant to the chaos of my life at that moment. And there wasn’t that much online, but there was some reference on Tumblr—somebody on Tumblr said something like “You think Bobby Gladden was a Columbiner?” And I thought, “What’s a Columbiner?” I just clicked on that tag, and found that whole world.

At that time, at least as I encountered it in 2012, the Columbiner community was mostly girls using the language and tropes of online crushes to talk about Columbine. There had been a few pieces written about them, and those pieces had mostly taken a predictable angle: “Oh dear, what is becoming of these girls? Let’s wring our hands. How alarming.” But what I had noticed, in reading through the Columbiners’ posts, was that they were extremely media-savvy. Nobody is more media-savvy than a teenage girl—and aware of the layers of representation, and what is allowed, and what is taboo. They’re constantly paying attention to that.

They were playing with that shock: they knew that what they were saying was shocking, and it was taboo, and they were kind of making fun of it, and they were kind of making fun of themselves, and they were kind of making fun of anybody that would freak out about them. But then, even amid that layer of joking or irony or play, there was also a real sincerity, and often a lot of real pain. There was also, it seemed to me, a real sense of community there.

And so I was just like, “What if we took them seriously? What if instead of immediately condemning them or wringing our hands again, we asked ‘What are they saying here?’” And so that was what that essay came out of.

BLVR: It feels like whenever we talk about teenage girls and their behavior, it’s not even really about the substance of the behavior, it’s just suggesting that whatever they’re doing is irrational and extreme, because they’re the ones doing it.

RM: Right. Somehow, we want to dismiss teenage girls’ behavior and say that it’s stupid and vapid, but that it’s also frightening, and a harbinger of the end of society. So it’s both frivolous, and deeply alarming and dangerous.

BLVR: What do you think is so scary about the force of a teenage girl’s feelings?

RM: Well, I think they’re super intense, and I think that’s palpable. There’s power there—it’s that power that’s scary. And non-normative desire, too. And partly it’s just girls asserting that they have desire, that they’re not just the objects of it. And then what they desire being something that doesn’t fit into our framework.

BLVR: What do the Columbiners desire?

RM: It’s hard, in some ways, to talk about them as a group. For some of them, it was this very tender thing, and they just wanted to love and understand these boys, the Columbine killers, or to save them. Sometimes it was that they wanted to be the boys, they wanted to dress up like them, they did dress up like them. Sometimes it was wanting to be a partner in crime. That’s a trope you see a lot: everybody else dies, but I’m the girl who lives, or I’m the accomplice, or I’m the one who doesn’t get destroyed. I’m aligning myself with this power.

And sometimes these girls themselves were dealing with a lot of pain and bullying and social anxiety, and there was something in these boys—whose diaries have been published online now—that they really related to. As a teenage girl, you don’t get to read a lot of teenage boys’ diaries. Dylan Klebold’s diary, particularly, is very sensitive in parts.

It was so easy for me to imagine how I could have, if I were born ten years later, been a Columbiner. Probably not one of the gore-glorifying ones—but I can imagine myself being young and sentimental on Tumblr, for sure.

BLVR: What were the technological means of obsession available to you when you were a high schooler?

RM: It’s so funny, that ended up being a surprising theme of this book: technology, and what mechanisms of communication exist, and how that shapes these obsessions. When I was in high school, I was involved in some message boards. That was a scene that was going on. But not crime message boards—music message boards. In terms of consuming crime stories, when I was in high school, it was pretty much just the big paperbacks. It felt very solitary to me, and something that I should keep secret.

I also consumed crime through mass media of course: shows like Cops or America’s Most Wanted or Unsolved Mysteries, that were like “Now let’s all gather around the TV and watch a really bad re-enactment of a kidnapping.” One of my brother’s friends was a child actor, and his big role was being kidnapped in a reenactment on America’s Most Wanted. I remember him just looking angelic as a kid, and like, pre-kidnapped in that way. He was so cute he was definitely doomed.

You know? Just like, “You didn’t have a chance, kid.”

[Laughter]

BLVR: Like the John Mulaney line about how, according to the New York Post, there are two kinds of kids in the world, tots and angels, and a tot is an angel who hasn’t died yet.

RM: That’s amazing.

II. Killer Airtime Hogs

BLVR: This is something I feel like your book really approaches from a lot of different directions: That white women have learned we matter in America essentially by being pre-victims, as a demographic category.

RM: Yeah. It’s so messed up. Seeing your potential victimization overrepresented is, in some ways, a total curse and a burden—and in other ways a total privilege. I think being inundated with images of what could happen to you warps the psyche, certainly, in some ways. But so is having the real troubles and victims in your community—like a lot of women who are not attractive young middle-class white women—be largely invisible in our culture.

BLVR: It feels like there’s a profitable industry—or many profitable industries, really—based on enacting and selling your unwanted thoughts, or creating fears and anxieties for you to have. And based on creating fears for society at large to have about this idea that attractive young middle-class white women are continually under assault, and we need to do whatever is necessary to protect society from the dark forces that are preying on our women, the women that belong to white America. Which feels very Birth of a Nation, when you boil it down that much.

RM: It’s such a funny way to talk about crime, too. If you talk to any sociologist, or someone working in criminal justice, they will tell you that crime exists in these larger structures of poverty and desperation and unequal allocations of resources. But instead we get these stories that are about individual monsters preying on individual women—almost as a way to keep us from thinking about those other ways that we could be conceiving of talking about crime.

BLVR: I’m trying to find a passage in Savage Appetites—oh yeah, here we go. I’m going to read a little bit of you back to you.

RM: Oh no.

BLVR: You write:

Most of the killer-centric media I consume at least ostensibly condemns its subject. But a clear ambivalence is at work, too. Would any of us linger so long if there weren’t? The killer, or at least the version of the killer who hogs most of the airtime, is set apart from the rest of humanity because of his bad deeds, but that apartness also marks him as exceptional. Something of the animal is in him, and also something of the artist. He’s a mastermind, someone who doesn’t play by the same rules as the rest of us.

I don’t know if we believe that more in America in this moment than we did in the past, but it certainly feels like a load-bearing narrative within American culture as we know it today.

RM: David Schmid, who wrote Natural Born Celebrities, has a take you might be interested in: that there is this relationship between the FBI and Hollywood, and after the 60s and 70s, after all these assassinations, and revelations about things like MKUltra and the way the intelligence agencies were investigating MLK and working to infiltrate and undermine the anti-war movement and the Black Panthers—there was a real national suspicion of them. They were not seen as these cool good guys in suits. Schmid’s thinking is that this led the FBI to promote the serial killer as a nightmare figure. This idea wasn’t in the public consciousness until the 1970s, really—that there are a ton of these brilliant, intricately twisted, sexually motivated psychopaths, pure evil monsters stalking among us, picking out strangers to assault and kill, and that you need an agency that can cross state lines to stop them.

Schmid makes the point that to rehabilitate their reputation, the FBI put the spotlight on the handful of men who were like this. I’m not saying that they don’t exist, but that they were amplified: that by amplifying these stories, and really getting them out there, the FBI could be heroic again.

BLVR: To me, the archetypal mastermind serial killer that we know from the media is someone who loves attention, and is in fact extremely audience-oriented.

RM: Totally.

BLVR: Fictional serial killers, like the one in Copycat, are often committing these really elaborate murders to communicate with the cops or the media—and it’s like, just send a letter. Or tweet at them.

But it feels like, with the fictional serial killers, we’ve maybe invented a justification for ourselves to be obsessed with media about real serial killers, because we see them as creatures of the media who are focused on us, and not on their own compulsions.

RM: And then it justifies paying this obsessively close attention to them. But again, most of these guys are so banal, they’re so boring, you can ask them a thousand questions and you don’t get insight. You can watch The Ted Bundy Tapes all day, and that’s not going to really tell you why—

BLVR: Because whatever they can tell you about themselves is limited by the limits of their own self-insight, and by definition, as a serial killer, you’re not a very emotionally healthy person.

RM: Exactly. We’re obsessed with the idea that somehow there’s a message that we’re not quite getting, and that somehow it’s a message we need to hear. And that we would be better for hearing it. You can read all of Klebold and Harris’s writings that you want, and it basically boils down to the fact that they were really angry at the world. There’s not a secret code there.

BLVR: One of the moments that to me feels almost like an implied thesis of the book—

RM: Oh my God, tell me, I need one.

BLVR: Okay, I’m gonna tell you your implied thesis. In the opening pages, you write: “I learned that the Columbine killers’ journals were online and I read those, too.” And then, in the very next sentence, you write, “That year, as my roommate vegged out to shows with spaceships and cyborgs, I once again sought out a different flavor of escapism.”

Anyone who reads that will either understand or not understand how true crime, even or especially if it’s about a terrifying premise, is escapist. And if it is confusing to you, then the book, as you go through it, will try and bridge that gap, and show you the escapism possible within stories that are about things we hope to never encounter—generally hope to never encounter—in our actual lives.

RM: Yeah. But don’t you also feel like there’s some level of attraction to these moments of heightened intensity? Not that people desire to be murdered, exactly. But with some of the Columbiners, you get the sense from what they wrote that on some level they wished that they had been there during this important, intense time.

III. “Holy, symbolic, silent.”

BLVR: In “The Victim,” you write about the birth of the victims’ rights movement, and how new of a construct it is. You talk about how the category of victim shifts, and becomes not just people who have been victims of violent crime, or who are the survivors or the communities of those people, but anyone who imagines they could be a victim of crime.

RM: Exactly. The idea of who was allowed to be a victim, who was welcomed into this community of victims, was, like you said, expanded into people who felt like they could be victimized. But it was also narrowed, and people who were not considered the “innocent victim”—whatever that means—were excluded. And so you end up having a category of victim that largely means “white women”—or “white people,” but specifically “white women.”

Some of the victims’ rights reforms are really crucial, really positive. If you think about what they ended up getting Acosta on for the Jeffrey Epstein stuff, it was that he didn’t follow the federal rules that are in place about victim notification. Or the hundred-plus victim impact statements against Larry Nassar, read aloud in court. Things like that are really powerful and important. What becomes troubling is when there’s a narrow band of people who are afforded that right, and who get to publicly occupy that role of the victim.

BLVR: One of the things you talk about, that I find really useful for thinking about what has happened politically in the past few decades, is that it feels like victims’ rights have become at least as much about having people speak for victims as it is about victims.

RM: Yes.

BLVR: And this role the victim takes on is an extremely politically meaningful tool. Especially the murder victim, because if you have been murdered, then you can’t contradict anything that someone is doing, politically, on your behalf. You write: “Because she’s dead, the victim can become whatever people need her to be. Because she’s dead, we can say anything we want about her, and she can’t talk. For some people, she is more valuable this way: holy, symbolic, silent.”

RM: Over and over again, people use victims as a kind of shield. It’s like the bulletproof vest of political rhetoric. Donald Trump tweeted the perfect example of this the other day, after the shooting in El Paso. He basically said that the way to respect the victims is to support law enforcement and to shut up. If you criticize him, if you criticize his racist rhetoric, you’re harming the victims. And it’s convenient for him that the victims are dead, so they can’t contradict him.

BLVR: I find so fascinating your descriptions of the attachments to people have to Sharon Tate—the desire strangers have felt, over the years, to grieve her murder. Would you call Sharon Tate an archetypal American crime victim?

RM: Yes. She became so much more famous in death than in life. She was considered a little too vapid, a little too sexy, when she was alive—and then once she was dead, it was much easier to make her into an icon.

Poor Sharon. I do wish she had been able to be old and fat and happy. I really can picture it.

BLVR: The mental image I often have for a woman who died young, and especially who the public fixates on in this way—I like to picture her old and not giving a fuck anymore, and finding it hilarious that everyone’s obsessing about a picture of her from when she was twenty-five.

RM: I think the thing that’s messed up about these iconic victims like Sharon Tate—the beautiful sexy dead women—is that their lives get reread as if their violent deaths were somehow inevitable. I think that plays into why a lot of people find true crime relaxing—because it lets us off the hook: not only does it reaffirm that we’re safe, we’re not the ones who get hurt, but it also tells us we don’t need to do anything. If you say about these women, “Well, she was doomed, can’t you see the tragedy in her eyes?”—that completely lets us forget the fact that we, as a society, have often failed these women.

BLVR: I think the comfort of being swept along by the fable is that you feel like everything happened as it had to happen.

RM: It’s like, “She was marked for death”—no, she wasn’t. But society prefers her when she’s dead.

BLVR: The romance of the killer, to me, comes from the fact that he’s the one who makes you matter.

RM: Totally.

BLVR: There are servant girl possession stories from Puritan America—interestingly, servant girls had a tendency to get possessed, maybe because if you were being possessed by the Devil, you couldn’t do chores, and it was potentially the only way to get leisure time—and they go something like: a servant girl was tarrying on her way home, and the Devil appeared and bade her to write her name in his book and said he would grant her the powers of a witch. It’s this very romantic image: you’re walking through the forest and the dark figure appears, and he’s the one who can make you matter more than the other girls.

The serial killer figure, the Satan figure, the Hades figure: he has a seductive quality, if you have this knowledge that’s implicit in so much of the society you live in, that the way you matter and the way you’re deserving of adoration and protection is if something terrible happens to you.

RM: Right. Or you’re interesting if you’re in proximity to evil, but not destroyed by it. Like how hard society hates, and condemns—and is fascinated with—women who marry killers in prison. Everyone is so obsessed with that storyline.

BLVR: You say in the book that everyone assumed you were writing about that.

RM: Everyone thinks I’m either writing about female murderers, or women who marry murderers. Those are the limited places that people’s minds go when you say you’re writing about tropes of women and crime.

But it’s interesting to me how those women get condemned, sometimes with more ferocity than the men who did the killing: these women who have found this abject and corrupt and tragic way of being in proximity to this particular kind of power. We prefer to think it says something terrible about them, the women, instead of something terrible about patriarchal violence.

BLVR: It also seems that one of the things we miss, by seeing the killer as this outlier figure—who’s somehow beyond humanity, beyond society—is that the people American women should be afraid of are the men in their lives.

RM: Right.

BLVR: And the way we fixate on certain kinds of crime allows the people we should really be scared of to continue what they’re doing unchecked.

RM: That, to me, is one of the saddest things about the satanic panic: you have this moment when the culture is finally starting to pay attention to abuse, and to the sexual victimization of women and children. And then maybe it’s too much to look at—because if you look at it too closely, it totally implicates the nuclear family, because that’s where this violence actually tends to happen. And so, instead, we have to invent these cartoon characters of evil, that are like the opposite of a family, and blame the problem on them.

BLVR: Like how the satanic panic disproportionately prosecuted women and lesbians. So a lesbian is like, the opposite of a male, heterosexual head of household. I guess.

RM: Exactly! Like, that child who seems to be trying to tell you something about somebody who hurt him or her—certainly don’t pay attention to his father or uncle. Maybe he has an aberrant daycare teacher somewhere in his life. Who’s also a witch.

BLVR: Maybe there’s a lesbian somewhere.

RM: Maybe there’s a lesbian witch somewhere! Let’s look for her.

BLVR: In your chapter on Columbiners and mass shooters, you write: “Amid all this darkness, it’s possible to see the faintest glimmer of a silver lining. The proliferation of random violence means that killing strangers is no longer a surefire path to becoming famous.”

RM: It is interesting to think about that in this period we’re living in, when—you would never know it from listening to a bunch of the podcasts out there, or from listening to the president, but violent crime is on a historical decline. The kind of violence that is increasing is this spectacular mass violence.

BLVR: It feels like there’s some possibility of redemption hidden in the fact that we’ve become so inundated with mass shooter or attempted mass shooter stories, because with this kind of exposure, it’s hard to hide from the fact that these men are really boring.

RM: Exactly. We’ve passed through that phase that happened right after Columbine, where it was like, “No, we need more information, we need to know everything, we need to see everything, we need answers.” And then we realized that there aren’t answers to be had—or that we’re looking for the wrong kinds of answers. We’re asking the wrong questions.