Just before my first novel came out, I dove into Tash Aw’s fourth novel, We, the Survivors, desperate for the distraction. I’d long admired Tash’s work, and I knew I could count on a richly textured world and a fascinating story—a book that would swallow me whole.

We, the Survivors did that, but it also startled me. It made me resketch the contours of what a novel is, and what writers can do. Is it strange to say the novel—with all its brimming anguish—inspired me?

The story is deceptively, unsettlingly simple: the narrator, Ah Hock, is a Chinese Malaysian man who can’t seem to find a foothold to climb away from his origins of rural poverty. We learn he has killed someone: a Bangladeshi migrant worker. As Ah Hock tells the story leading up to the killing, he speaks to a faceless “you.” At one point, he says, dully contemplating an alternate life, “Maybe I could’ve been you.” Fifty pages in, we learn that the addressee is Su-Min, a well-meaning, young, foreign-educated researcher who is interviewing Ah Hock after his release from prison. The divide between them is palpable and uncomfortable; Ah Hock receives his groceries from a church, while Su-Min refuses his meal offering because she is off carbs “at the moment.” She’s fiercely principled, railing against government corruption, though her principles are sometimes out of place, or costly, in his world.

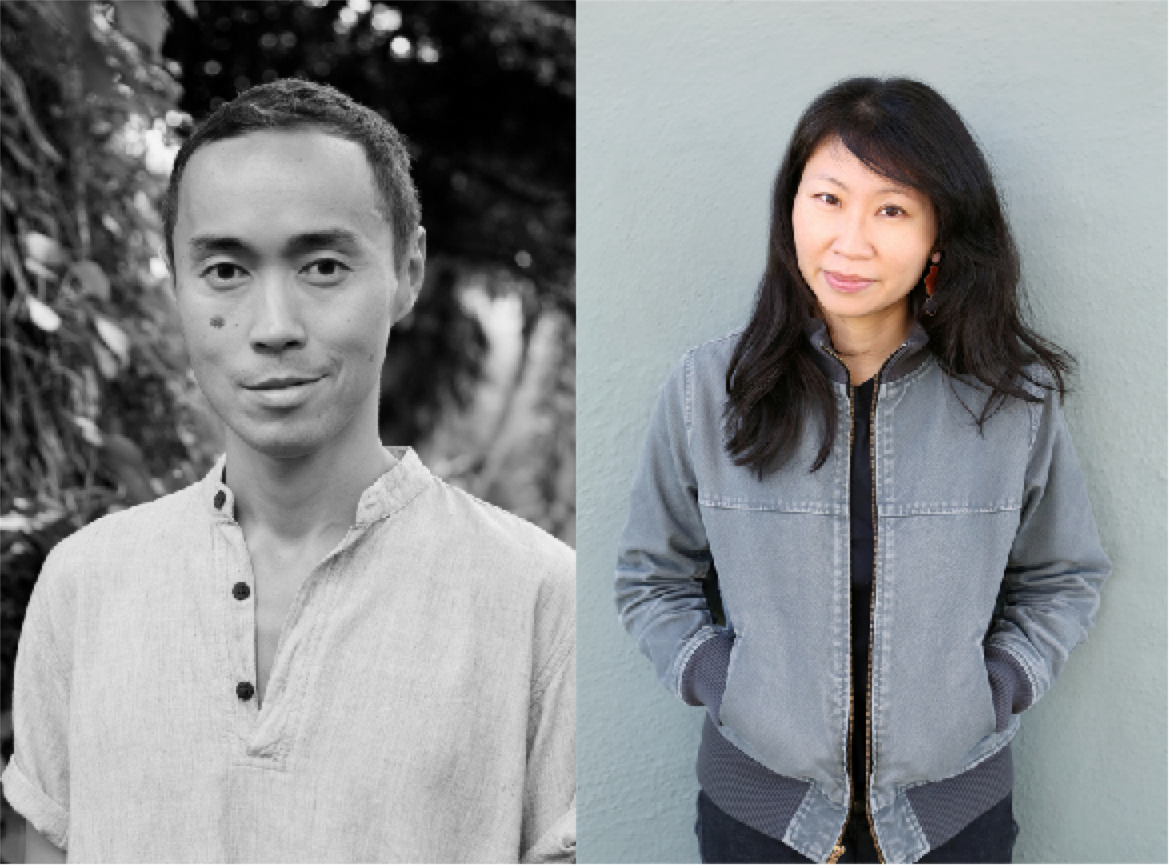

Even after that “you” takes on a name, a face, a distinct personality, it still continues to ring in our ears. It’s me, I think. Ah Hock is talking to me. The novel is set in Malaysia’s central region, but its preoccupations have obvious, painful parallels to American issues today. I had to know more. Tash Aw gamely sat through a lengthy video chat from his temporary apartment in Paris, where he’s a fellow at Columbia’s Institute for Ideas and Imagination. He’d magnanimously, alarmingly, read my novel. He spoke in whole, lucid paragraphs. Later, I realized I’d asked just one question over and over again: how did you write something that both implicated and sustained me?

—Chia-Chia Lin

I. “You’ve turned into a white child, an ang mo kia”

CHIA-CHIA LIN: You’ve now completed four novels—so many, I can’t imagine it. How have your inquiries stayed the same or shifted?

TASH AW: When I started writing, I wanted to interrogate what it means to be Asian and living in the times I’m living in—how people’s ambitions and desires and fears have changed over the last sixty since Malaysian independence. So many of these stories are closed off. Particularly as immigrant families, we were engaged in the act of survival: finding...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in