“Her life is a kind of life that doesn’t exist anymore, or is really rare. This sort of small town life where your entire family is around, and you know everyone in town because you’ve lived there your whole life. She’s an eighty-six-year-old woman but she’s not lonely or isolated in the way people often seem to be now. She belongs to a community. And I really long for that.”

Three of Kathryn Scanlan’s Preferred Objects:

Dogs

Potatoes

Hair

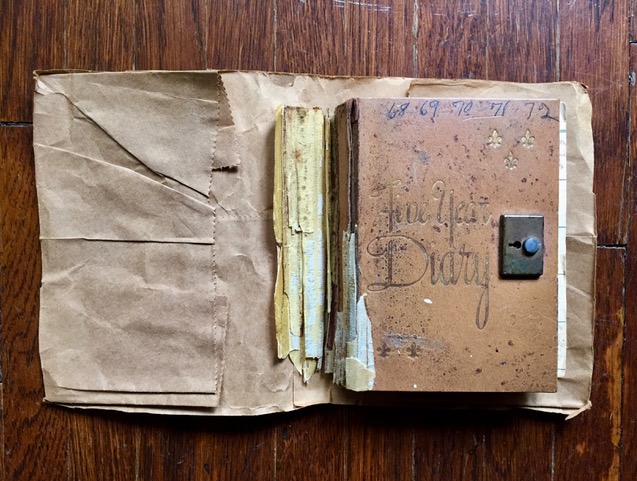

For over a decade, Kathryn Scanlan “edited, arranged, and rearranged” a small selection of text she’d made from a stranger’s diary found at an estate auction. The result of this work is Scanlan’s debut book, Aug 9—Fog, and in her introductory note Scanlan asks of the diary, “Why does it compel me so? Isn’t it terribly banal?” But the language throughout Scanlan’s book is surprising, so full of texture that I found myself copying down many of the pages. “Vern put me a light in ceiling. Put light down in Vern’s lungs. Putting up pictures. Blowed up cooler in eve.” Another: “All kinds of roads. Dead end roads, roads under construction, cow paths & etc but had good time, a grand day.”

This diarist began keeping her five-year diary when she was eighty-six years old. She painted, knitted, did jigsaw puzzles, canned food, made frequent visits to the cemetery, and lived among family and friends in an Illinois town where she knew her neighbors. Scanlan organizes her book by season and uses the diarist’s wide-ranging and particular observations to create a narrative filled with little delights and all the stuff that makes up a life.

Kate Zambreno writes in The Appendix Project, “I wish often for writing to do what sculpture or collage does. How can writing achieve dimensionality, be aware of space? A paragraph like a frame, a box, or a room. Can one walk around a paragraph?” Aug 9—Fog is composed of pages that invite one to walk around in them. We read into such lines as “Mother & daughter banquet, we didn’t go.” We learn of a neighbor’s death with, “She looked very nice. Lots beautiful flowers.” Though spare in words and slim of spine, Aug 9—Fog demands attention, and each time I read it, I see something new in it—a focus on colors, on patterns of sounds.

I first encountered Kathryn Scanlan’s work in the pages of NOON, a literary annual where I am currently a senior editor. In May, cross-legged on a couch, on a tree-lined street in Brooklyn, Scanlan and I discussed process, diaries, compression, as well as her stories, which are forthcoming in a collection from Farrar, Straus and Giroux called The Dominant Animal. Scanlan sits up straight and moves with precision, her manner as purposeful as her prose. I had forgotten to move during our conversation, and by the time I stood up, my legs had gone numb. I mentioned this to Scanlan, who commiserated, though it wasn’t until I got home and copied down more pages from her book that I realized tingly legs and feet are not overlooked by the diarist either.

—Liza St. James

I. Wrangle the Language

THE BELIEVER: You have degrees in writing and in painting. Do you still paint?

KATHRYN SCANLAN: I don’t, but I’ve been thinking about getting back to it. You need space for it, especially if you’re using oils. For a long time I rented studio spaces; I shared them with my husband. At a certain point I decided I wanted to focus on writing, which is funny because I had a painting teacher in college who told me I would have to choose whether I wanted to pursue writing or pursue painting. I rejected the idea at the time, but then that’s what ended up happening.

BLVR: I don’t know if that happened, actually. [Laughs.] For you, I mean. Some of your images become paintings for me long after I’ve read them. Two in particular from your short story “The First Whiffs of Spring” come to mind. First: “I took a bus past the old dairy with the big metal cow out front. The cow had long, thick eyelashes and pink-painted lips like a human woman’s.”

And, “In the bathroom, someone had painted bright, childish flowers along the bottom of the wall, giving the impression that the flowers were growing from the linoleum floor.”

These both happen to include the word “paint,” but others that don’t are also very visual.

KS: It’s a very visual process when I work. I make images in my head and try to wrangle the language in a way that it can build those images.

BLVR: I love, for example, your story “Small Pink Female.”

KS: I think that story started with an image of flowers—I used to work in a flower shop. Or, no—it started with me trying to figure out how to describe a terrible date.

BLVR: A date? That you went on?

KS: No, not that I went on. When I started writing it, I had recently gone to Jumbo’s Clown Room in Los Angeles. Do you know what that is?

BLVR: No.

KS: It’s a strip club, or more like a burlesque club. The dancers are very good, very powerful. I’ve heard David Lynch used to go there to drink coffee and write. Anyway, for some reason I’d gone there and I was thinking about it and about other strip clubs I’d been to. I was playing around with writing a story about a guy who goes to a place like that on the regular, but then the story swerved and I started talking about a flower shop instead. [Laughs.]

BLVR: Do you remember anything about how that swerve happened?

KS: I started writing it and got stuck, and I was working on something else about a flower shop, so I ended up combining them. That happens a lot. I’ll be working on a dozen stories at once, and often I’ll take something from one to use in another. That’s a technique Diane [Williams] has really helped me cultivate. It was something I’d done to a few of my stories, but she made it clear that this was something I should be doing because it can have such a rich result.

BLVR: Since you brought us to Diane Williams, I’m curious about how you came to NOON. Your first published story was “Line,” in the 2009 edition. Do you remember what that process was like?

KS: Well, I loved that it was a mail-in situation. So I wrote her a little note as I do now, and mailed it. She got back to me really quickly, and proposed changing the ending. My draft ended with some dialogue and another couple sentences of exposition, but she proposed changing the dialogue and ending it there.

I had the two characters going back and forth, saying “yes” and “no,” having a more normal-seeming conversation, but she pushed the dialogue into a more absurd realm. Having an editor do that, I was at first very taken aback, very surprised. But then I recognized the value of it. Of being able to learn from that, to learn from her as an editor. I saw the generosity of her editorial style, her willingness to spend time with the work in that way. It was such an important early encouragement of what I was trying to do—it set me on my path.

And then I started working on the diary project and sent that to her, and she seemed really excited and moved by it in the way that I did. That was so thrilling, because I was trying out this weird thing, not sure if anyone else would care about it, but she was interested, and that encouraged me to continue, to make what eventually became the book. The influence of Diane and of NOON is very strong in this book.

BLVR: When you submitted “Five-Year Diary” to NOON, what did your note look like for it?

KS: I sent it to her without any context, alongside a few other stories. I think I had the idea at that time that I wouldn’t write an introduction, that I would just present it as-is, as this mysterious thing. So that’s how I sent it. But Diane later suggested I write something to introduce it, and it did seem important to acknowledge where it came from.

[Scanlan pulls up email correspondences with Diane Williams from 2009 on her phone.]

KS: I guess I was the one who suggested using the images. When that [2011] issue of NOON was coming together, I was moving from Illinois to California, and it was a really hard, tumultuous move. I sent a lot of the physical fragments, scraps and things that had been tucked into the diary, to someone who was going to professionally scan them to use in the issue. But when I moved, I didn’t have an address for a while, and when the person who’d scanned them sent them back to me, he sent them to my old address, and they got lost in the mail. I was devastated by that.

Some of the scans are in that edition of NOON, but not all of them. There was one scrap—the only thing written on it was “aug 9—fog.” That’s where the title of the book comes from, and that’s one of the pieces that got lost in the mail.

BLVR: In one of your notes you describe the way she ignored the things the diary told her to use the pages in the back for—anniversaries, etc.

KS: Yeah—she used those pages in the back to write more diary instead. And she inserted things like a list she made of all the people who died while she kept the diary, and the date they died. What people died of, when they got sick, when she got sick—virus pneumonia in 1950-something, she made a special note of that. When she put new shingles on her roof years earlier, and how much she’d paid for it.

BLVR: That’s something I love that you maintained. The sense of everything brushing up against each other. It’s exciting to read. Between the people, the animals, the weather, there’s so much that makes its way into such a small amount of text. How did you end up with pages like this?

KS: I’d thought about trying to make visual artwork from it for a while, but it never seemed like the right thing to do. I kept looking at it and I kept thinking about it and I really liked it just as an object at first, and then when I read it I liked it for other reasons. I wanted to make something out of it even though it was obviously already something, and for a long time I tried to figure out how to do it.

When I started reading it I started typing every sentence that interested me, so by the end I had this sort of head-long, run-on document. And I edited from that to make my NOON piece. When I sent it to Diane, she said she would need to pare it down, but then when the time came, she said, “I couldn’t cut any of it.” I was like, “I know!” [Laughs.] I felt the same thing, like, Oh this is too much, but then when I tried to remove things, I couldn’t do it. I think the encouragement from her and having it in NOON gave me the confidence to do something else with it, but I wanted to try a different approach.

I pictured it from the beginning as sort of a poetry book, something that would give breathing room to the density of the NOON iteration. Around that time I had read Mary Ruefle’s A Little White Shadow, and the idea for the book came from that world. Stripping away to get to the poetry of things, allowing space around the sentences to give them weight.

II. Joshua Tree

KS: I didn’t start working on it as a book until a year or two after I moved to California. From the time of the move until then was a period when I couldn’t write anything; I couldn’t read. It was awful. It was really terrible. I was living in this 350-square-foot house with my husband and I couldn’t write, and I also couldn’t find a job, I felt very stuck and dead, so I got the idea I’d create a residency for myself.

I messaged a woman on AirBnB who had the cheapest place I could find in Joshua Tree, and it ended up being this strange situation where she was going to be out of town but she had all these animals, and her house was mid-renovation, so it was a wreck, so she couldn’t really rent it out for money anyway, so she said if I stayed there and took care of her animals, I could stay for like a month and she wouldn’t charge me. So I did and it was crazy! It was a very frustrating time actually, because I was frustrated in general and hadn’t been able to write, but that’s when I started writing stories again and that’s when I started working on this book.

BLVR: Were you alone in Joshua Tree?

KS: Mmhmm. I had my dog with me. It was out, out in the desert. There were a few other houses around, but I couldn’t tell whether anyone lived in them or not. I didn’t have a car. The town was miles away.

BLVR: How did you get there?!

KS: My husband dropped me off and left me. [Laughs.]

BLVR: That’s the dream, and also kind of a nightmare.

KS: Yeah, exactly. It was both.

BLVR: Okay, so you’re alone in this house, you have your dog and you’re taking care of what other kinds of animals? I’m getting creeped out just thinking about it, even though I love Joshua Tree.

KS: Two other dogs—I love it, too, but it also creeps me out. It’s a weird tension. There were two goats also, and there were chickens. One of the woman’s dogs would attack the chickens and steal the eggs, so I had to keep him away from them. The goats were small but really volatile. They would buck and butt me with their heads and try to stomp my dog. [Laughs.]

BLVR: Had you taken care of goats before?

KS: I had never taken care of goats. I had a horse growing up. I had a lot of animals growing up, but never goats. Goats are intense. They jump up on anything, they eat everything.

BLVR: When you went there, you brought the diary?

KS: I brought a lot of stuff. I brought a box of books and the diary. There was a sunroom with a desk on one end of the house, and that was where I’d work every morning until it got too hot. It was incredibly hot—it was summer. My husband came out one weekend to visit and restock my food supplies, and I talked to him on the phone a few times, but other than that I spoke only to animals for about six weeks.

Some friends stopped by near the end and it was like I’d forgotten how to interact with humans. I remember coming to the diary every day, feeling so frustrated with it, that I would never be able to do with it what I was trying to do, but a lot of that was the pent-up energy I was struggling with at the time.

BLVR: When you left Joshua Tree did the pages have about the same amount of words on them as now?

KS: Maybe a few of them did, but they looked very different, and for the most part were different in their content. At first I was trying to figure out how a page would look. I tried different margins, different spacing, because I felt the visual aspect was very important. Arriving at the short, justified blocks was a process. I think in that early draft, most of the pages were probably longer, more paragraph-like, and I continued to strip away and rearrange in the years after that. I imagine it seems like such a simple book. But it really was this kind of gigantic process of figuring out how to arrange which sentences or words on which pages, and then which of those to cut, because I ended up cutting a lot of those, and then changing some of them and deciding which ones went together. And they’re in no order compared to how they were in the diary.

BLVR: Reading it, the NOON version especially, I felt bombarded and sort of exhausted by… life. Here it’s more well-ventilated, but a similar intensity compounds, I think.

KS: That feeling of bombardment is how I felt, too, while working on it. I wish I had it for you to look at—I should have brought it. It’s, you know, it’s small, but it’s almost 400 pages long, and she filled every—I mean every page is filled to the max. And she cramped her handwriting around to fit things in—and for five years she did this! For a long time it overwhelmed me. I needed this process of years and years to whittle it down in this way to get at what I felt was its essence. Obviously I’ve exerted a sort of authoritarian editorial presence onto this document, but I think that was my attempt to meet this feeling of being overwhelmed that I had from it.

III. Intimately Peopled

BLVR: The diarist has a lot of people around that she knows very intimate things about—about their bodies, about how their days went. There’s something about how intimately peopled this person’s world is that kind of made me feel lonely.

KS: There’s a little bit of that sadness in it for me, too. Because it does feel like her life is a kind of life that doesn’t exist anymore, or is really rare. This sort of small town life where your entire family is around, and you know everyone in town because you’ve lived there your whole life. She’s an eighty-six-year-old woman but she’s not lonely or isolated in the way people often seem to be now. She belongs to a community. And I really long for that.

BLVR: Do you want people to see the diary? Do you wish everyone could see it who wanted to?

KS: For a long time I didn’t want to have it associated with this book at all. I felt like I needed to divorce the nostalgic, sort of heavy, sentimental presence of this water-damaged broken object from what I was trying to do textually. I felt I had to strip the diary of its physicality to make it into what I wanted it to be, to get at what I was trying to get at. So I don’t view it as companion material, I don’t feel like people need to see it to understand my book. But at the same time, I still love looking at it. It’s beautiful. And maybe for people who are interested in the book, it’s something that could be exciting to them. I don’t want to necessarily withhold it. Because I’m excited by it, too! So it’s fraught.

BLVR: You had it for a while thinking of it as an object, and then you eventually decided to try to read it—do you remember anything about that moment? Was it a moment?

KS: Around that time, I’d recently read an interview with Lydia Davis, where she talks about encountering Beckett’s work when she was in her early twenties. To learn from him, she would type out his sentences. That really resonated with me because it was something I’d tried with certain texts I didn’t understand. I mean, there’s the practice of re-reading and re-reading things, which I do, but there’s something about the act of actually copying out sentences to figure out how they work. So that was in my head when I began.

This is something I do regularly with whatever I’m reading—I copy the sentences that jolt me into my notebook. It’s a way of trying to understand why some sentences are so much better than others. Then, when I began actually working with the diary sentences, editing them, I remember feeling a little bit like: well, this is a very weird thing to do, what is this? But also feeling very free to do what I wanted with the material.

BLVR: Was there anything in the text that you weren’t sure about—scribbles or things that you couldn’t quite make out—that you kind of “translated” into language?

KS: There are a lot of things in there that are difficult to read or blotted out by water that I puzzled over. There were times when I made leaps based on what had come before, thinking, Well, she’s probably talking about this, or she probably would be using this word or saying something like this here. But for the most part I let the illegible things remain illegible—there was so much material that was readable.

BLVR: You did a ton of rearranging, but are the sentences or phrases more or less intact?

KS: They’re mostly intact, but sometimes I used parts of sentences and sometimes I changed a word or omitted words or made other adjustments—I adjusted some of her spelling, for example. The sentences I ended up using represent a tiny fraction of the original diary. Maybe like one or two percent of the lines from the original have been used, and those I’ve manipulated in some way, whether within the sentences themselves or in their juxtaposition to others.

BLVR: You described those last pages filled with other things. Do you think she kept another diary?

KS: I don’t know! A lot of her notes in the back were things that had happened years, sometimes decades, earlier, which made me think this might have been her first diary. I can’t imagine keeping a diary to the extent that she kept this one, where it became this project she was committed to for five years, and then to suddenly be like: Oh well, I’m out of pages, so I guess I’ll stop. It seems like she would have gotten a new one, for sure. And kept doing it. But I’ll never know.

IV. “I painting”

BLVR: I was drawn to the fact that the woman in the diary paints. It seems there’s so much going on, and still “I painting.”

KS: I love that she painted! That was definitely one of the first things that caught my attention. Not only that she painted, but that she phrased it in such an idiosyncratic way. It really drew me, you know. That got me.

BLVR: I wish I could see some of those paintings.

KS: I know! There’s something about the way she talks about her painting elsewhere—it comes up a lot in the diary—that leads me to believe they might have been paint-by-number. She talks about painting on her “deer scene,” or her “mountain scene” that so-and-so gave her. But then again, she might have just meant my mountain scene, you know, as a way to describe what she was working on. Who knows? That’s the thing—there’s a lot of mystery. But I love that she had this activity. She didn’t seem to watch much television, you know, she was knitting, and spending time with family and friends, and canning food, and painting on her porch. Whether it was a blank canvas or whether it was paint-by-number doesn’t matter to me at all.

BLVR: Is recording the stuff of everyday life art?

KS: I think it can be. There has to be a particular kind of mind at work. I do think the diary is a work of art. But as I read it, I was thinking of how I would edit it, which is actually how I read everything. And I felt that by editing it, I could make something new. My parents are antique dealers and have given me other journals and handwritten things they’ve found, and most of them don’t interest me as much as this diary interests me. There can be an impulse in journaling to make yourself look good, to try to impress whoever might be reading it in posterity—which brings up the motivation for keeping a diary, which is something I think is really interesting. There can sometimes be a tendency for a kind of bullshit posture. I feel like the magic of this diary might have something to do with her age, but I think it also is just her as a person, her voice, her mind, the way she used language and the things she observed and noticed.

BLVR: An idea that a lot of people have about diaries is that they’re a place to explain or record or even work through thoughts.

KS: And that’s why I think her age has something to do with why I like her diary so much. She’s not trying to figure out who she is. She knows who she is. She’s just living day to day, in the moment.

BLVR: “Some hot nite.” “Eyes got the glimmer.” “My feet smelled some.” There’s a lot of texture.

KS: What makes the diarist’s language so unique is that it sounds like a mix of old and new. She was born in the 1880s, she was a young woman in the early 1900s. I think you can hear that in her speech, an older way of using words and phrasing things. But she also makes what seem like very contemporary moves, like her use of “nite,” and the way she abbreviates and condenses her experiences. It makes me wonder about our conceptions of “modern” and “antiquated.” I’ve come across letters written over a century ago that sound like the most avant-garde writing you’d find today.

V. Knowing Your Objects

BLVR: In your craft essay for Granta, you write, “Christine Schutt—paraphrasing Gordon Lish—says, ‘Your obligation is to know your objects and to steadily, inexorably darken and deepen them.’” I’m curious what you think of as your objects.

KS: Ashton [Politanoff] told me that potatoes come up a lot, which now I notice more. Food in general. Dogs and animals.

BLVR: Yes! And I’ll add hair. There are so many indelible hair images in your stories.

KS: You’re right about hair. I was really interested in hair objects for a while. I mean I still am, but I was actively trying to collect things. I have a locket—you know, hair art, Victorian hair art. They would take hair from the dead—or sometimes a woman would give a lock of her hair to her suitor or husband or whatever, but the really spectacular stuff I liked was for mourning, like these hair wreaths, and bracelets and necklaces made out of hair. It’s really incredible art.

BLVR: I read a wonderful short story featuring a hair museum, and I looked it up, and it exists. It’s called Leila’s Hair Museum, apparently started by a retired cosmetology teacher in Missouri.

KS: I was helping my family clean out my grandmother’s condo a year or two ago and we came across these envelopes my grandmother had that were full of her daughters’ hair from the 1950s and 60s. So there was this envelope full of my mother’s hair, and this envelope full of my aunt’s hair who had recently died, and this envelope full of my other aunt’s hair. That was such an intense thing to come upon. My mom’s hair from the early 1960s, when she was ten or twelve or something—it’s just white. Like white. She had white blonde hair until she had kids.

BLVR: And then it changed?

KS: They all did, her sisters, too, they all were blonde and once they had children their hair started turning darker, or at least that’s what my mother tells me. Or maybe it was just a coincidence because that’s when they were getting older.

BLVR: That reminds me, I think babies are another object of yours. [Laughs.] Strictly as objects!

VI. Diary as Textbook

KS: I already had these leanings about compression, trying to strip things away to say what you want to say in as little space as possible, but there was something about working on [the diary] that really cemented that for me. I do think the stripped version is almost always the better version. I know a lot of people would disagree with me and say that they’d like to have more language, more description, more understanding. That they want to revel in and luxuriate in a long descriptive passage or whatever.

BLVR: But you like Rachel Cusk.

KS: I do like Rachel Cusk! I only just recently started reading her, and I’ve only read Outline, but she’s doing something I find to be really interesting. I think because of my interest in compression, I tend not to read a lot of novels—newer ones, anyway. I sort of have to force myself to read a contemporary novel. And a lot of the time, I don’t make it through. But in Outline, it’s like the artifice of the novel has been stripped away.

BLVR: You’ve also mentioned Maggie Nelson as an influence.

KS: Yes, I love her work. For some reason I’d never read Jane, and a couple months ago I finally read it and was like, Oh my god! She makes poems from her aunt’s diary, and intersperses those with her own poetry and conversations she’s had with her mother about her aunt, newspaper articles and snippets from this terrible book that was written about her aunt’s murder, and kind of collages all of this stuff together. It’s brilliant. In addition to the diary project, I’ve been trying for years to figure out what to do with a lot of the found materials I’ve collected.

One of the moves I love in Jane is that she makes poems from, I think it’s her great-grandparents’ letters back home to Sweden after they immigrated to the United States. I have an ongoing poem document I’ve made from things written on old postcards, and because of that, those letter-poems in Jane sounded so familiar—the sort of wistful yet matter-of-fact reporting back to the people at home. But a lot of her found documents were written by family members, and most of mine were written by strangers.

When I was trying to figure out Aug 9—Fog, there were several draft manuscripts I made where I combined excerpts from the diary with other things, like the postcard poems and found photographs. And I tried pairing it with some of my writing, too, things like lists and some Oulipian experiments I’d done. Jane was really an interesting book to read in that regard—seeing her do these things, these similar sorts of impulses I’d had.

BLVR: When you were describing having documents from other people’s stuff, not necessarily your own family, that’s something that occurred to me—it’s not an object, but more a current. A sniffing around, a trying things out, a longing to be taken in. Not just in “The Candidate,” but that kind of feeling occurs in your other stories, too. And I feel that myself. [Laughs.]

KS: It is! It’s looking everywhere at everything and everyone and listening to everything, what everyone says, to try to pick up something that might be important. Or to find something of meaning or value out in the world because you don’t have anyone.

BLVR: I think that’s key, the feeling of not having anyone. Or even if you have family, always wondering what that means. Can you find more family?

KS: Yes. I have family, but I’ve always had a feeling like I’m on my own, like I’m on the outside looking in, trying to figure out how this world works, how this society works, how other people relate to each other. I often feel like a voyeur, like I’m looking too closely at something that should be private. But I think the impulse is essentially a longing for connection, or understanding—so I tend not to look away.