T

he border of southern Arizona and Mexico is more desolate than one might think. South of the highway between Tucson and Yuma lies the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, where pilots drop explosives over millions of acres of uninhabited land. There is also the Tohono O’odham Nation, which is now split by a border that is not its own. On either side of the Tohono O’odham lands are national parks, and the occasional town along a two-lane highway. At night, the main source of light is the stars.

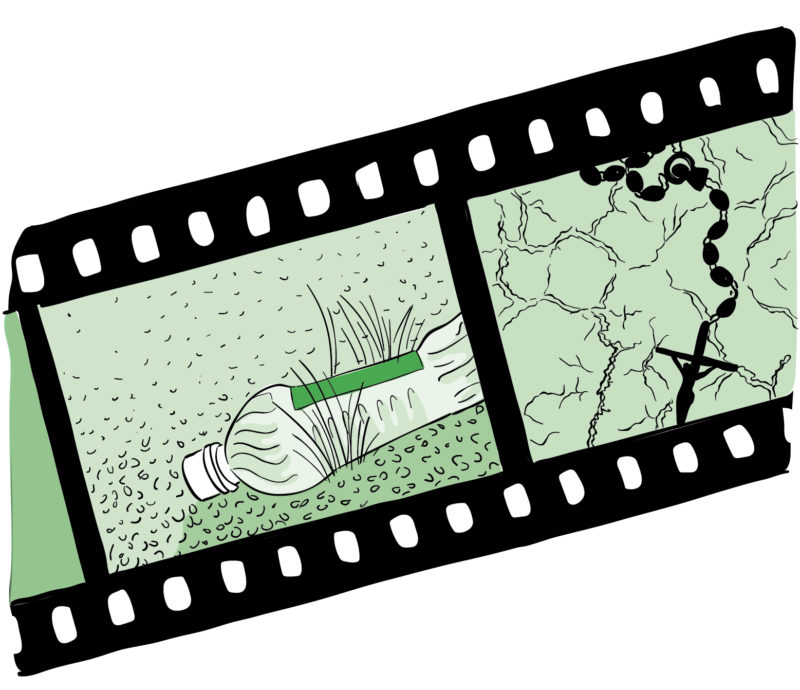

Along these highways there are checkpoints, strategically placed so people cannot move between towns without encountering Border Patrol. Since I am a citizen of the United States, my presence on the border is regulated, but I am not at risk. I am not often questioned beyond the requisite “Are you a citizen of the United States?” I am allowed to move in this space more easily than nonwhite people, or people who aren’t citizens, which is one reason I felt I should come here. I first came to the border to volunteer with a humanitarian aid organization that leaves gallons of water, cans of food, and dry socks along well-traveled routes in the desert. The hope is that people crossing will find them.

The summer temperature in southern Arizona is regularly 100 to 115 degrees. Doctors recommend that a person who’s exerting themselves drink four glasses of water an hour in such temperatures. It is impossible for someone to carry enough water to stay hydrated for the three to four days it takes to walk from the US-Mexico border to a major town or highway in the US. Dehydration begins as thirst, and in this heat it quickly leads to headaches, fainting, nausea, organ damage, and death. Since 2001, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner has recorded more than three thousand migrant remains recovered in southern Arizona. There are likely many more that will never be found. Finding a stash of water can save a life.

People walk through the desert when they have few other options. The number of people migrating in this manner increased in the late ’90s, after the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) enacted a policy called Prevention through Deterrence, which increased security in cities like El Paso and San Diego to limit migrants’ ability to cross in urban areas. This forced people out...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in