The first time I tried on the Mushroom Death Suit, my head got stuck halfway through the black funeral shroud. I hadn’t undone enough buttons at the neck. The eco-friendly burial outfit, made of biodegradable cotton, comes in two pieces: a black hoodie with attached mittens and a pair of footed pajama bottoms. Patterns of white stitches branch, like a cell’s dendrites, along the shoulders and hems. With its black fabric and ivory embroidery, the ensemble could be a cross between a gothic straight jacket and Bob Dylan’s Western-style Manuel Cuevas suit from the late nineties—the black one with white piping that the musician wore at his performance for the pope. On my own shroud, a face-flap folds down from the hood and wooden buttons run down the arms, legs, and chest, for the easy dressing of a rigor mortised corpse. Head still stuck inside the suit, I thrashed my arms. “Get it off me!” I gasped to my husband, David.

Because I’m a mycophile—mushroom lover—drawn to the macabre, I’d been excited about an emerging mycotechnology designed by Jae Rhim Lee, founder of the green burial company Coeio. A friend, recalling that I teach a college class on the grotesque, had recommended Lee’s TED Talk: “Saw this and thought of you.” Throughout the talk, Lee struts across the stage while modeling her eco-gothic funeral suit embedded with a mix of microorganisms and mushroom mycelia—those fungal networks of threadlike cells that give rise to the fruiting bodies of mushrooms. The goals of Lee’s mushroom suit, summarized on Coeio’s website, are threefold: to “aid in decomposition, work to neutralize toxins found in the body and transfer nutrients to plant life.” Although mushrooms resemble plants, they don’t photosynthesize. Fungi comprise their own scientific kingdom. Like animals, mushrooms digest their food, though they do this externally, by excreting acids and enzymes into their immediate surroundings and absorbing nutrients through cell chains. Fungi help logs rot into rich layers of compost, building the depth and quality of the soil and stopping dead matter from clogging our environment. Without mushrooms, fallen trees would pile up to the sky.

“[F]ungi are the grand recyclers of our planet,” writes mycologist Paul Stamets in Mycelium Running, “the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community.” Certain fungi, known as saprophytes (from the Greek sapro: “rotten” and phytes: “plants”), feed upon decaying or dead organic matter. These industrious mushrooms—portobello, cremini, oyster, reishi, enoki, royal trumpets, shiitake, white button—speed up decomposition, restore and aerate soil, and provide food for other life forms, from bacteria to bears. “The yeasts and molds used in making beer, wine, cheese, and bread are all saprophytes,” notes journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone in Mycophilia. So rot-eating fungi helped civilize us, Bone notes, “if you consider good wine an indicator of civilization.”

“Fungi,” Stamets adds, “are the interface organisms between life and death.” During the cycle of rot and renewal, saprophytes degrade toxins, including a number of industrial chemicals and heavy metals we absorb through our skin and carry in our bloodstreams throughout our lives. Many of the bonds that hold plant matter together resemble those found in petroleum products, which make mycelia especially adept at remediating a range of toxins that are carbon based, such as oil, gasoline, diesel, petrochemicals, pesticides like DDT, and agents of chemical warfare like sarin gas and VX. Saprophytes also degrade fertilizers, textile dyes, and munitions like TNT. Stamets coins the term mycoremediation for the use of select mushroom mycelia in breaking down toxic waste, turning harmful pollutants into benign metabolites. Jae Rhim Lee’s mushroom suit offers a way we might employ mycoremediation in green burial practices: using mycelia to filter toxins from rotting corpses and enrich the soil, minimizing the environmental impact of our deaths. Even in cremation, Lee observes, we release mercury from burned dental fillings into the atmosphere. And in green burials that simply skip the embalming process, our flesh still leaches industrial chemicals into the dirt.

After watching a recording of Lee’s 2011 TED Talk on what she then called her Mushroom Death Suit (it’s now marketed as the Infinity Burial Suit), I began longing for my own shroud. I imagined entering its dark folds, my flesh becoming food for mushrooms. The notion at once pleased and appalled me. At the time, Lee’s burial suit wasn’t yet commercially available, so I waited several years before I could finally click “add to cart.” At thirty-seven, I bought myself a funeral shroud. I hung it in my closet, a black phantom next to my Anthropologie dresses, and imagined my future life as a mushroom. In some dark folktale, a girl foraging by herself in a forest strays from the path to pick and eat a few bites of magical fungus-Anna, my flesh plumped and multiplied.

I haven’t always been a lover of mushrooms. As a kid, I’d pick them off my pizza or spoon the grey lobes from Thanksgiving gravy. The slices reminded me of the detachable ears of my toys, Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head. As a teenager, I’d munch the dried caps and stems of hallucinogenic mushrooms, of the genus Psilocybe, in the parking lot of Phish concerts. The fungi smelled like mothballs and black tea. If I ate too many, I’d puke until I stilled the ripple in my gut. Mushrooms were a nasty handful I’d chomp down and vomit up in order to dance and spiral my hands in front of my face, watching the flesh-colored trails streak and helix through the air. The shrooms would stick in fibrous plugs in my molars and tasted like bitter peanut butter.

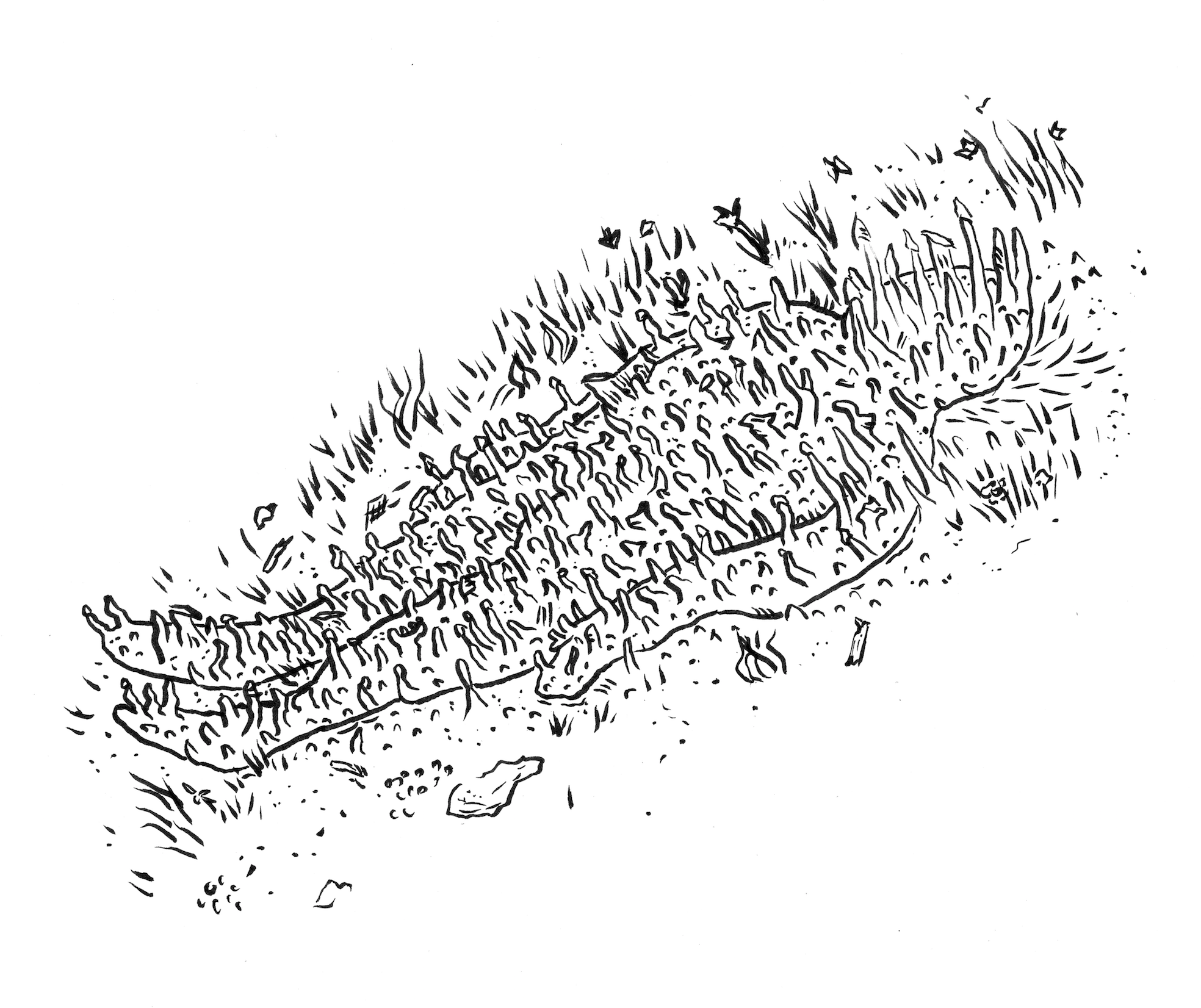

My early association of fungi with sliminess, severed ears, and drug-related barfing suggests I’d assumed a mostly mycophobic attitude toward mushrooms. Something about their tendon-like firmness and salamander-scent made me recoil. In the essay “Fungi, Folkways and Fairy Tales: Mushrooms & Mildews in Stories, Remedies & Rituals, from Oberon to the Internet,” research plant pathologist Frank M. Dugan suggests that while many eastern European cultures tend to be pro-mushroom for the most part (mycophilic), western European attitudes toward fungi have historically been much queasier (mycophobic). In Russian folklore, for example, a largely mycophilic genre in which tales frequently link mushrooms to magic, the witch Baba Yaga possesses a “dual character.” She can morph, in an instant, from cruel to generous. As kids, my sister and I would curl into either side of my mother as she read the Slavic folktale to us in her terrifying witch-voice. In this version of the story, Baba Yaga hunts for mushrooms in the forest, where she encounters a hedgehog nosing around for fungi. Although the witch at first considers eating the animal, she decides to spare it. The hedgehog then turns into a boy with supernatural powers. Baba Yaga is also affiliated with the benevolent spirits who live under mushrooms, Dugan notes, and she often appears in illustrations standing in a dense, wild wood, a crop of red-capped fungi at her feet.

Whereas eastern European attitudes toward mushrooms often tend toward the mycophilic, the folkways of western Europe generally portray a more fearful stance toward fungal magic. In Holland, one superstition says the devil rests his milk churn within circles of mushrooms called fairy rings. In Dutch and Flemish art from the Renaissance, mushrooms function as symbols of hell, like the toadstools that erupt near a urinating amphibian in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s engraving The Last Judgment. In Wales, folk beliefs predict that if a grazing animal crosses into a fairy ring, its milk will sour. Victorian artists complicated British mycophobia when they revised the supernaturalism of mushrooms, making fungi’s link with fairies more benign. No longer malevolent hell-molds, mushrooms became adorable elf-furniture. Although Victorian myco-revisionism heavily influenced English illustration, as in Beatrix Potter’s intricate watercolors of fungi, Anglo-Saxon attitudes toward mushrooms have remained fraught. From a mycophobic perspective, mushrooms become metaphorically and literally shady characters: entities that thrive in darkness and dampness, operate in subterranean covertness, and remind us of death and rot. Ghoulish and grey-faced, they betray us by breaking those carbon bonds that hold our bodies, and our world, together.

In Molière’s neoclassical comedy, Tartuffe, the seventeenth-century French playwright names his titular character after the Old French word for “truffle”: that pungent, hard-to-find fungus that grows underground. The religious hypocrite Tartuffe insinuates himself into a bourgeois family as the spiritual advisor to the gullible middle-aged head of the household, Orgon. Under Tartuffe’s influence, Orgon betrays his own family: He tries to force his daughter to marry the con artist; he accuses his wife of lying about Tartuffe’s sexual advances; and he disinherits his son after signing over the estate to the swindler, who attempts to evict Orgon and the rest of his kin. Molière ends his play with a royalty-flattering deus ex machina: the king, who’s savvy enough to sense Tartuffe’s duplicity, saves the day and sends a bailiff to arrest the criminal. Tartuffe, like his namesake truffle, thrives in darkness and concealment—the phony and the fungus are similarly difficult to expose.

In the last stanza of the poem “The Mushroom is the Elf of Plants” (1891), Emily Dickinson imagines her own mushroom-related betrayer:

Had nature any supple Face

Or could she one contemn—

Had Nature an Apostate—

That Mushroom—it is Him!

In a variant on the quatrain, Dickinson aligns her contemptuous mushroom explicitly with Judas Iscariot, the notorious disciple who in Christian narrative betrays Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane for thirty pieces of silver, identifying him to the chief priests with a traitor’s kiss:

Had nature any outcast face,

Could she a son contemn,

Had nature an Iscariot,

That mushroom,—it is him.

Although I miss the former stanza’s excitable punctuation (“it is Him!”), I prefer the latter’s more damning and particularized metaphor, “an Iscariot,” in which the mushroom becomes the Judas-face of nature. After all, the apostate here isn’t some trivial, Tartuffe-like religious hypocrite: this tiny fungus comes to us direct from the underworld to undermine the whole of humanity. The mushroom, as a Judas-sign, reminds us of all that’s ephemeral, grotesque, and treacherous: a small fleshy body that revels in rot and feasts on our own inevitable decay.

Many common names of mushrooms conjure anatomy, often recalling our earthiest bodily functions or most vulnerable parts. There are the obvious caricatures and slurs of fungi that resemble cocks: the Pricke Mushroom, Shameless Penis, Stinkhorn, Satan’s Member. And the names of some mushrooms known as puffballs (for the way they “puff” spores from their caps) make a fantastic, flatulent menagerie: Wolf’s Fart, Fairy Farts, Ox Fart. I’m also partial to fungi that form fragmentary portraits: Red Mouth Bolete, Tooth Fungi, Fuzzy Foot, Dead Man’s Fingers.

The mushroom that captivates me the most, however, is the one Dickinson claims as nature’s apostate: that edible tree-fungus found in savory stir-fries, Auricularia auricula-judae, whose common names include the anti-Semitic smear the Jew’s Ear, the Wood Ear, the Jelly Ear, and my favorite nom de shroom: the Judas Ear. The mushroom, which ranges in color from rawhide to henna to peach, recalls the shape and lateral surface of the human ear’s whorled auricula: its ridged helix and antihelix, its nubby tragus, its meaty lobe. While some Judas Ears look as supple and fine as a baby’s apricot folds, others gnarl and scallop and sag as if attached to the grotesque head of an old elf. As the fungi cluster up trunks and across stumps, they seem to turn their would-be ear canals earthward, as if listening for gossip or a far off cough. The Judas Ear fruits from rotting wood, including the decaying bark of elders. According to some versions of the apostle’s death, Judas hangs himself in despair from an elder tree after he learns that Jesus will be crucified. This story imbues the Judas Ear with self-negating connotations as well as an especially gory corporeal vista: the flesh of the suicide swinging by a rope, his neck broken, his head askew, his ear flushed with blood and bent toward us like the edge of a fungus.

In the final days of my six weeks of training to volunteer for a suicide prevention hotline in Los Angeles, I pressed my ear to a telephone’s receiver for a four-hour required listening session. I kept my line muted during the observation while a seasoned counselor fielded calls from people in crisis. A decade earlier, my own voice had filled a volunteer’s ear with a plan—pills, hotel, note. I realized, though, after four hours of keeping my ear flush as a fungus to other people’s death-wishes, that I couldn’t do this. I hung up. I knew I’d never be able to come back.

Each time I search for photos of Judas Ears online I leap down the Google-rabbit-hole. I scroll through dozens of pictures: lobe after lobe growing up the black bark of decaying trees. I’ve even begun dreaming about the mushroom. Mostly the Judas Ear appears in my nightmares: I pry a handful from a stump, drop the mushrooms into the hammock of my T-shirt, where they morph from fungus to flesh. Or: I find a package on my doorstep, cut open the box, and discover someone’s mailed me pieces of a body. Or: I sit in a booth at the crisis center, drop the phone from my face—to escape the voices of the suicides—and see my own ear still attached to the receiver. When I’m awake, I daydream about the tree mushroom, repeating its mellifluous syllables, seductive as a taboo. Everyone knows a Judas. And unless we’ve been lucky, everyone’s been a Judas, too. Maybe this is why the fungus’s doubled nature lets me love it even as the Judas Ear fruits corpses in my nightmares. Why the mushroom can shift from teriyaki-tart bite to body part in my mouth and, still, I won’t spit it out.

According to Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox dogma, the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist transform into the body and blood of Christ through the miracle of transubstantiation. The metonymy for the savior’s body is bread—hearty, wholesome, broken with others in fellowship. The synecdoche for Judas is a humble fungus, a shape-shifter, a hanger-on. The body of Christ; the cup of salvation. The body of Judas; the rotten kiss. In the communion of Judas, not only does that macabre mushroom conjure the body of the apostate—betrayer of his friend and then of his own flesh—it envelops all of us. The Judas Ear’s reminder: we’re all corruptible.

Our bodies reach a determinate form early in the stages of human development. Unless we undergo an amputation or suffer from some radical accident, we keep the same number of limbs; we make use of only one brain; and, allowing for an increase in pounds and a decrease in bone density, our general shape remains the same. Not so, however, with mushrooms. Fungal indeterminacy means mushrooms must be expert adapters, wily survivalists that respond to ever-changing experiences and extreme environments. After all, we’re currently living in the age geologists have dubbed the Anthropocene: an epoch whose timeline begins with the rise of modern capitalism and in which the ecological effects of human disturbance outpace those of natural disasters. Unlike us, fungi don’t die from old age, notes anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in The Mushroom at the End of the World, her study on the commerce and ecology of the rare matsutake mushroom, famously the first living thing alleged to grow from the ashes of Hiroshima. Tsing’s book, subtitled “On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins,” explores matsutake mushrooms in the context of precarity (anthro-speak for economic and social instability), looking to the fungus as inspiration for collaborative survival in tenuous times. “Many are ‘potentially immortal,’” Tsing writes of fungi, “meaning they die from disease, injury or lack of resources” but not due to the outer boundaries of a determinate form’s lifespan. “We rarely imagine life without such limits—and when we do,” Tsing continues, “we stray into magic.”

Although I’m an atheist, I love the magical thinking behind Christmas rituals. As a child, though, I never thought to ask about Santa Claus’s red and white costume. Did I assume his suit’s festive colors had something to do with candy canes or the red velvet cake my mom baked and spackled with cream-cheese icing? In the 1998 Presidential Address to the North West Fungus Group, titled “Fungi, Fairy Rings, and Father Christmas: The Mythology of Fungi,” Sean Edwards discusses the compelling theory, supported by much circumstantial evidence, that our jolly commercial deity emblazoned on Coke cans was once a mushroom-gathering Siberian shaman. Santa’s outfit may recall both the fur-trimmed hats and boots worn by the nomadic reindeer-herding Koryak, an indigenous population of the Russian Far East, as well as the colors of their favorite psychedelic fungus, Amanita muscaria, which they’d consume in shamanistic practices. With its red cap as wide as a tapas plate, striking white spots, and chubby stalk, Amanita muscaria presides as our iconic fairy tale toadstool. The fungus appears in countless illustrations of enchanted woodlands, often with a frog, elf, fairy, or forest gnome resting on top. Your smartphone’s mushroom emoji is Amanita muscaria. Despite its whimsical appearance and folksy polka dots, however, the fungus is highly poisonous. The common name of Amanita muscaria, the Fly Agaric (“agaric” refers to a gilled mushroom), may derive from its function in various folkways as an organic pesticide. In medieval Europe, some people crumbled the Fly Agaric into cups of milk and left the mixture in windowsills to intoxicate flies, which drunkenly crashed into walls after drinking the brew. Lewis Carroll likely had the Fly Agaric’s scale-altering perceptual effects in mind when he imagined his Wonderland fungus—the one whose flesh makes Alice grow and shrink depending upon from which side of the mushroom she eats.

Despite the risk of fatalities, the shamanistic Koryak ate the dried Fly Agaric as an agent of divination, which enabled them to commune with supernatural forces—talk to the gods. According to Edwards’s lecture to the fungus society, the Siberian reindeer enjoyed hunting for psychedelic mushrooms, too. The animals apparently traveled for miles to find the Fly Agaric, munched on the fungi, and entered into a trancelike state, sometimes collapsing on the ground. The reindeers’ intoxication made the creatures easier quarry for the Koryak to slaughter, and the roasted flesh often retained hallucinogenic properties.

The research pathologist Dugan suggests in “Fungi, Folkways and Fairy Tales” that Santa may be a combination of the Norse deity, Wotan (Odin)—who wears a flowing beard and flies through the sky on a magical eight-legged horse—and a mushroom-tripping Siberian shaman. “His flight through the sky is shamanic,” Dugan writes, “and the association with reindeer is reminiscent of the Koryak custom of eating the flesh of bemushroomed reindeer to get high.” Additionally, Santa’s preference for chimneys over doors evokes the shamanic custom of exiting a dwelling through its smoke hole, according to the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. The person responsible for importing the mushroom-man and his herd of trippy reindeer into nineteenth-century American folkways may be one of two people: Clement Clarke Moore, an academic at the General Theological Seminary, or Henry Livingston, Jr., an author of light verse, former farmer, and major in the Revolutionary Army. Both men have at various times been named the author of the poem published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel, in 1823, “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (better known as “’Twas the Night before Christmas”). The poem describes a ritualized visit on Christmas Eve from a supernatural, fur-clad “jolly old elf” and adds a few pagan tropes to the character of St. Nicholas (Nicholas of Myra), a Greek bishop during the Roman Empire who was supposedly fond of secret gift-giving. “A Visit from St. Nicholas” became a literary sensation; the light verse poem established Santa’s reputation as our ambiguously arctic shaman and enduring late capitalist saint. The origin story of Santa’s mushroom suit got lost in the doggerel, however, along with the macabre doubles of his high-flying reindeer, the ones collapsed at the feet of the Koryak, lying in the red and white snow.

“Don’t fear the reaper,” I sang to David as I wiggled my hips and flipped up the hood of my mushroom burial suit. I looked like the black-robed skeleton holding a scythe on the cover of the Blue Oyster Cult’s “best of” album. Although I was giggling, I realized as I glanced down at my black-clad body that I’d probably never bury myself, or anyone else, in the mushroom suit. “It’s too ghoulish,” I texted my best friend, Alicia. “I would’ve gone with earth tones,” I wrote, “like the colors of a mushroom, and made it less straight-jacket-like, more of a flowing shroud.” Alicia texted back: “Do you think dead Anna will care about earth tones?” “Personally,” she added, “I prefer a mushroom death bikini.”

At its current stage of development, Jae Rhim Lee’s Infinity Burial Suit strikes me as more of a conceptual art piece than a viable commercial mycotechnology. Although people have been buried in the mushroom suit, including the invention’s “first adopter” Dennis White, a Massachusetts carpenter, the funeral product lacks mass-market appeal. At fifteen hundred dollars, Lee’s funeral shroud costs only a fraction of the price of mainstream caskets, but most folks don’t want go to a viewing and remember Uncle Jim in a Grim Reaper costume. Yet less obtrusive inventions, like a casket liner embedded with mycelia, can’t be worn for a TED Talk, and the hypothetical object wouldn’t wield enough of a visual shock. A mycotechnology that could pass for a yoga mat might impress you with its righteous green ethics, but it isn’t going to haunt your imagination like the image of the black hood. The mushroom suit is meant to appall: it’s a death cartoon, a gothic spectacle.

A widespread embrace of the mushroom burial suit in the United States remains unlikely for several reasons: mycoremediation is still an emerging technology; death-denial and corpse-preservation dominate contemporary funeral practices; and mycophobia holds us back from seeing mushrooms as agents of decay in a positive way. How long will fungi remain stuck in their myth as slimy, pint-sized Judases when their role as radical habitat healers is so profound? Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has this to say about the generosity of the fungus when it sups: “It makes worlds for others.” One reason people find it hard to appreciate mushrooms beyond their pasta-toppings may be because much of a fungus’s work is subterranean. Tsing calls this bustling mycelial realm “the underground city”—that network of branching cell chains that weaves its yellow-and-white sentient mosaic mostly out of our sight. We see the fruit but not the mushrooms’ deeper underworld. Another aspect of our shallow mushroom-gusto derives, Tsing suggests, from our understanding of life as dependent on species-by-species reproduction within the context of predator versus prey. Our narrative of self-replication, in which interactions with other species are cast as Wipe them out, blinds us to a more nuanced perspective on mutualistic relations in nature. “This self-creation marching band,” Tsing writes, “drowned out the stories of the underground city.”

Unlike Emily Dickinson’s mycophobic metaphor that evokes the Judas Ear as nature’s betrayer, Sylvia Plath’s fungus-loving poem “Mushrooms” enacts a fable of tenacity. Plath’s mushrooms speak in the giddy, conspiratorial voice of a collective “we.” Her personified fungi don’t exactly have mutualistic relations in mind. They’re less like Tsing’s generous world-makers and more like frightening guerrilla warriors. Plath’s mushrooms aspire to conquer the world:

Overnight, very

Whitely, discreetly,

Very quietlyOur toes, our noses

Take hold of the loam,

Acquire the air.

Plath portrays the stealth power of her mushrooms as she pairs wan or reserved adverbs (“Whitely,” “discreetly,” “quietly”) with aggressive or winning verbs (“Take,” “Acquire”). Her unassuming fungi only seem to be static. “They’re like rebellious 1950s housewives,” said an undergraduate in my fall seminar course on Plath. He pointed to the mushrooms’ descriptions of themselves as “Perfectly voiceless” and “Bland-mannered.” Plath wrote “Mushrooms” in November, 1959, before the rise of second-wave feminism in the early sixties. “Yeah,” another student chimed in, “this is Plath’s animistic attack on Eisenhower America.” “When the mushrooms say, ‘We are shelves, we are / Tables,’” she continued, “they’re using metaphors of domestic burden.” “[W]e are meek,” Plath’s mushrooms declare toward the end of the poem:

We are edible,

Nudgers and shovers

In spite of ourselves.

Our kind multiplies:We shall by morning

Inherit the earth.

Our foot’s in the door.

Like Dickinson’s allusion to the Judas Ear, Plath’s echo of the third beatitude from the Gospel of Matthew (“Blessed are the meek: / for they shall inherit the earth”) is both biblical and biological. After a meteorite struck the earth nearly 250 million years ago, at the cusp of the Permian and Triassic periods, an onslaught of lava, hot gases, and winds of more than a thousand miles per hour ravaged the planet. The vast dust-cloud of airborne debris blotted out the sun, darkening the globe and wiping out ninety percent of our world’s species. “Fungi inherited the Earth,” writes Paul Stamets, “surging to recycle the post-cataclysmic debris fields.” Like Plath’s guerrilla mushrooms, the fungal “Nudgers and shovers” multiplied to cover the blackened landscape, filter toxins from contaminated soil, digest the bodies of the dead, and rebuild species amid darkness and rot. Tiny mushrooms made possible the era of the triceratops. 185 million years later, another meteorite strike caused a second massive extinction that killed the dinosaurs, and, again, fungi spread to help heal the earth. Even as the mushroom reminds us of Judas, can’t it also be the phoenix, rising from the ashes to resurrect life?

My mushroom burial suit still hangs in the closet next to my cocktail dresses. Like biblical narrative’s most famous two-faced betrayer, my suit can change from friend to foe in an instant. Some days the mushroom suit seems comic and provocative, while other times it becomes monstrous, mocking, especially as illness begins its slow destruction of a loved one. Like my mother, diagnosed four days ago with a progressive brain and spinal disease. Right now I can’t look at that black hood behind me. The Judas Ear, as a metaphor, remains contradictory, like the opposite sides of the fungus from which Alice bites, or like the two shamanic mushroom-men—Santa and the Siberian—flying in their twinned but hardly mirror-image trips. “I’m not burying myself wearing it,” I told Alicia. I wouldn’t mind, though, if someone tossed in handfuls of mycelia after my body. “Wherever a catastrophe creates a field of debris—whether from downed trees or an oil spill—,” Stamets writes, “many fungi respond with waves of mycelium.” I’m trying to find hope here in the underground city. I’m cupping my hand to whisper into the Judas Ear. If we blow ourselves up in a nuclear war or a third meteorite strikes, I know mushrooms will begin their quiet work as they always have, thread by thread, rebuilding our resilient world in the dark.