Weather Reports: Voices from Xinjiang

We met in cafés and empty offices. A young wife spoke for the first time about her missing husband. A nephew had lost his aunt. Many mothers had lost many sons. Some had never shared their story with a stranger before. They sat on benches and in hallways, waiting their turn to speak. Some had left their villages before dawn to drive or hitch a ride to the city. When they finished, they stood up and went home again.

One man brought a tattered red-and-gold Chinese registration book belonging to his dead father, who peered out from beneath an imposing fur hat in the identifying photograph. Another man brought his two sons. A woman arrived with the names of her fourteen missing grandchildren. Some brought records of births and marriages, deeds, letters, family snapshots, petitions, or copies of UN conventions. Others were empty-handed.

They came to tell the stories of loved ones who are among the estimated eight hundred thousand to two million people believed to be detained inside concentration camps in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Some were former detainees themselves, victims of the most ambitious mass internment drive in recent history.

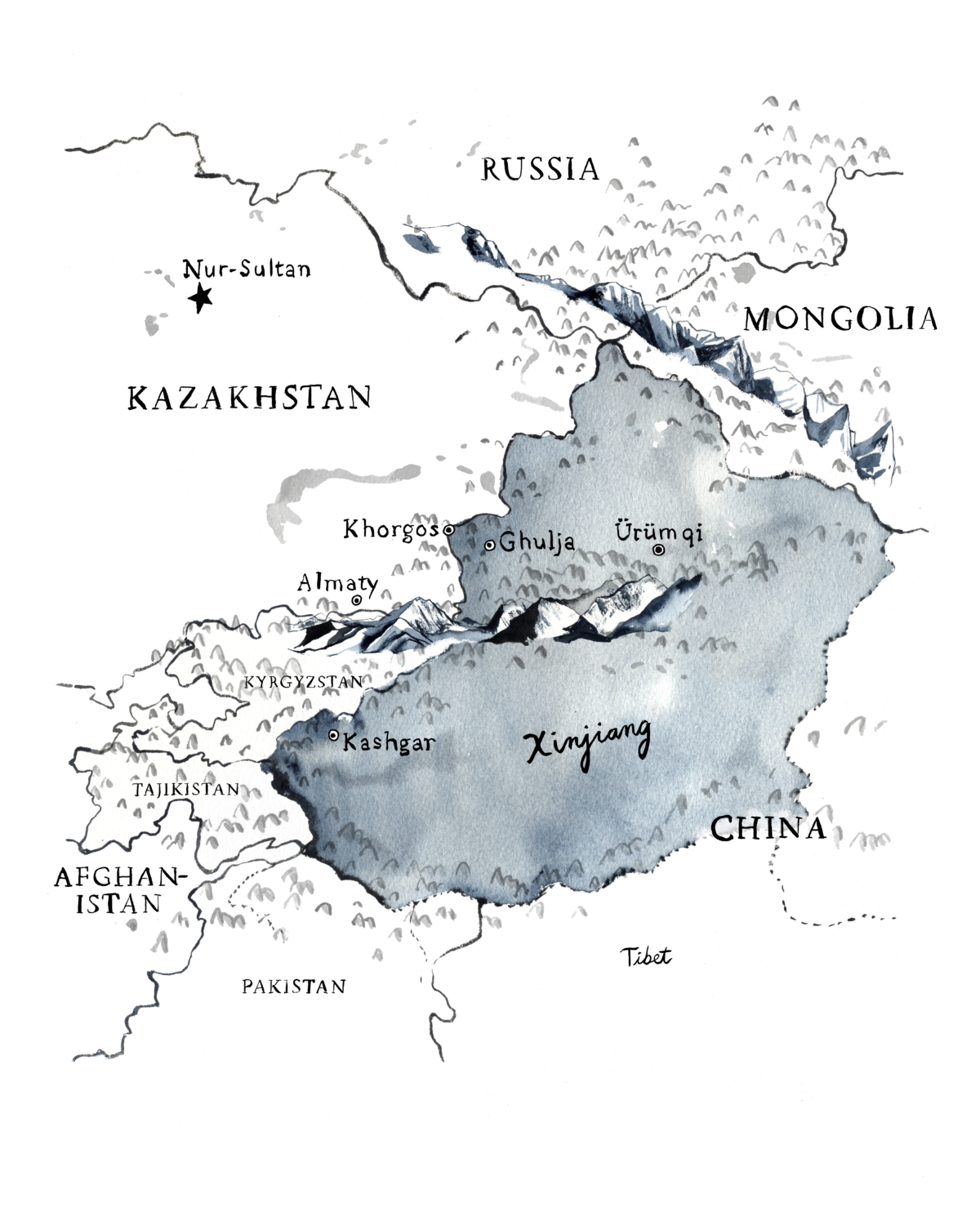

Xinjiang is China’s largest and most diverse administrative area. It is larger than any country in Europe save Russia—if it were a country itself, Xinjiang would be the eighteenth largest in the world—and, with around twenty-four million people, about as populous as Australia. It has sometimes been called China’s Muslim frontier. For centuries, Xinjiang has been home to a variety of Turkic cultures and ethnic groups, including Uighurs, who number more than twelve million in the region, alongside more than one million traditionally nomadic peoples such as Kazakhs, Mongols, and Kyrgyz.

In the 1940s, Xinjiang was briefly the site of a Soviet-sponsored East Turkestan Republic, and a strain of independence has long persisted among a small minority there. Following an increase in violence and suicide attacks, allegedly committed by Uighur separatists, in 2014 China launched its Strike Hard Campaign against the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism—a People’s War on Terror that soon metastasized into a war against all forms of Islam and virtually every facet of minority identity, including language, dress, and family ties. Over the past five years, authorities in Xinjiang have implemented the most advanced police state in the world. It is an exclusion zone of high-tech surveillance, roadblocks and checkpoints, the compulsory collection of biometric data, forced labor, and political indoctrination for millions of Turkic Muslims.

Chinese officials initially denied the existence of mass internment camps in Xinjiang. Since 2018, they have described them as vocational and educational centers for “criminals involved in minor offenses.” But leaked documents suggest that residents are targeted for detention en masse based on their ethnic background, religious practices, and any history of traveling abroad. According to one internal report by Xinjiang’s agriculture department, the drive has been so thorough that “all that’s left in the homes are the elderly, weak women, and children.”

No independent monitoring is permitted inside Xinjiang. State-sponsored tours for journalists and government emissaries are highly choreographed. The region has become a black box, with little reliable news getting in or out except through extraordinary channels: satellite photography, secret communications between family members across borders, and a handful of former detainees who have escaped China. Foreign correspondents who travel to Xinjiang are closely monitored and report being harassed, assaulted, and even kidnapped by authorities.

In 2018, I began to travel to Kazakhstan to interview the family members of Xinjiang’s imprisoned and disappeared. I also interviewed former detainees who described their own experiences. Most had crossed from China into Kazakhstan in the weeks, months, and years before our meeting, either by applying for residency and citizenship or by escaping across the border. The result is an oral history of life in contemporary Xinjiang. To my knowledge, it is the first document of its kind.

These accounts were recorded in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, in collaboration with the volunteer-run human rights group Atajurt. In spring 2019, Kazakhstan’s government curtailed Atajurt’s activities as part of a crackdown on public criticism of China; the group’s leader, Serikzhan Bilash, was arrested in March and placed under house arrest. The speakers here have nevertheless chosen to use their own names and the names of their relatives, despite the risks of censure in Kazakhstan and of reprisal for family members still in China. In doing so, they hope to pressure the Chinese government to reconsider its policy of mass detention in Xinjiang.

—Ben Mauk

INTRODUCTION

We do not have such an idea in China.

—Zhang Wei, China’s consul general in Kazakhstan, in response to a CNN report on mass internment camps in Xinjiang, February 7, 2018

We are trying to reeducate most of them, trying to turn them into normal persons [who] can go back to normal life.

—Cui Tiankai, China’s ambassador to the United States, November 28, 2018

Some international voices say Xinjiang has concentration camps and reeducation camps. These kinds of statements are completely fabricated lies, and are extraordinarily absurd.

—Shohrat Zakir, governor of Xinjiang, March 12, 2019

The situation there is absolutely stable and fine.

—Zhang Xiao, China’s ambassador to Kazakhstan, May 28, 2019

IF I RETURNED TO CHINA, MY DAUGHTER WOULD BE RELEASED

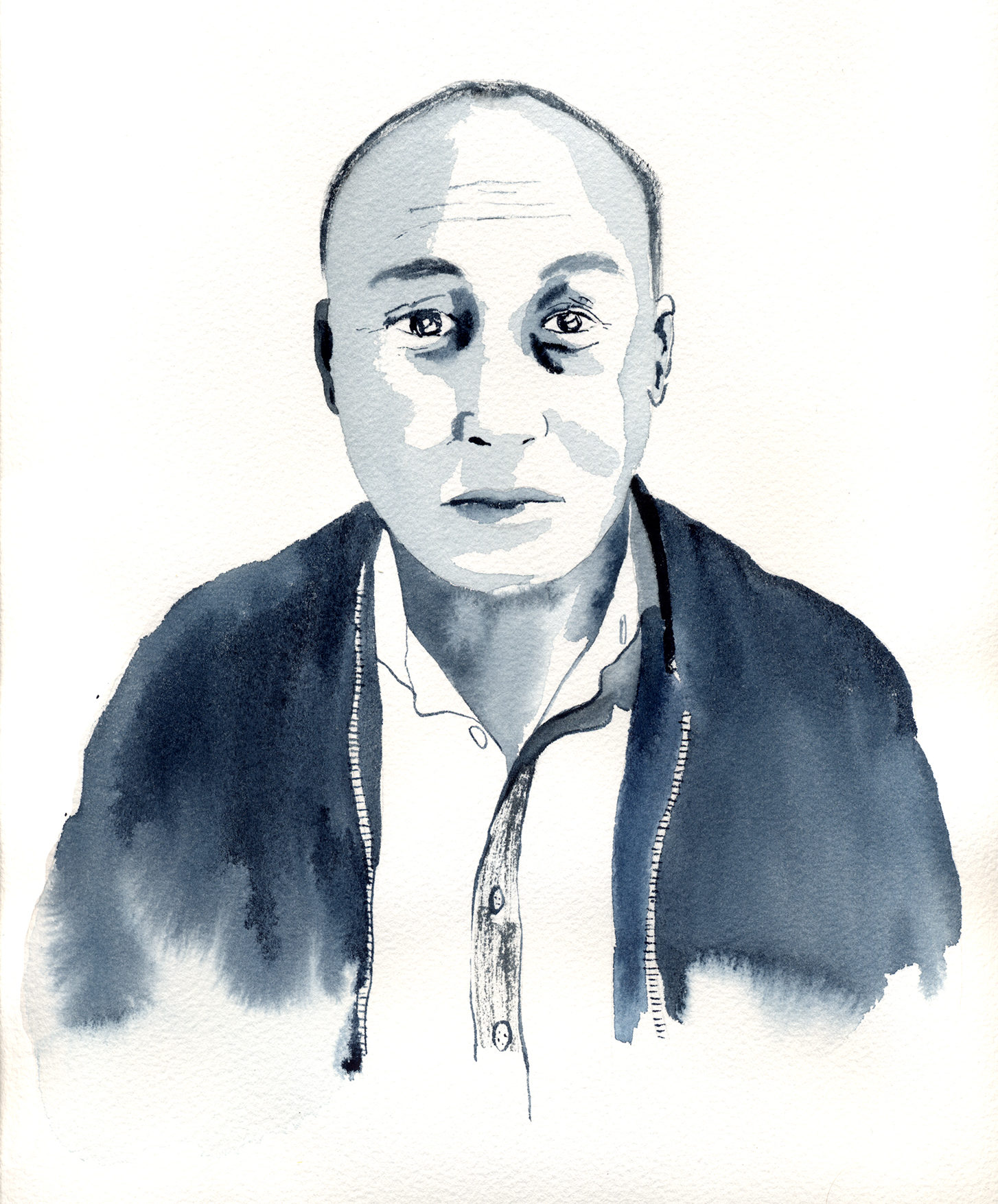

Kulzhabek is wearing a blue takiya embroidered with swirls of gold. Beneath it, the face of a worried father.

When my daughter was arrested, my niece told me not to call her. I’ll call you, she said. I was living here in Kazakhstan. My niece was in the village where it happened—the same village I come from, in China. For a few days, she updated me by phone. First she said the police were only checking Saule’s documents. I still hoped everything would be fine, even with my daughter in jail. On the third day, she was taken to the camp. My niece accompanied her there. That’s the only reason I even know what’s happened to her.

You see, back when I lived in China, I worked at the Oyman Bulak mosque. My first job was as the muezzin. I made the call to prayer five times a day. Over the next eight years, I eventually worked my way up to imam. The state itself sent me to be trained! That’s what makes all this so unbelievable. It was an official position. I was part of China’s official Islamic Association. The authorities said we could practice Islam and, at first, we could. But in April 2017, the situation changed. They started sending imams to camps. Then they began sending those preaching Islam to camps. Then anyone who knew anything about the Koran. Finally, they began arresting people just for having a Koran at home, or even for praying.

When it became clear I would be detained, I decided to flee and join my daughter in Kazakhstan. Up until that moment, I’d always done as I was ordered. You get a lot of orders as an imam in Xinjiang! I would take part in political classes whenever they asked, sometimes for weeks at a time. I always complied. But this time I was in a panic. I left my property, my home, my sheep and cattle. The only thing I thought to do was to hire a caretaker to look after my livestock.

When I got to Kazakhstan, the caretaker I’d hired called me. The local police had broken into my house. They were looking for forbidden books, he said. They wouldn’t have found any. All my books were stamped with the government seal of approval. But the call confirmed my fears. They really had come for me.

My daughter had graduated recently and found her first job at a corporate firm, a joint Chinese-Kazakh venture. The firm had her traveling between Kazakhstan and China. She had a Chinese passport and a Kazakh visa. It never occurred to us that anything might happen to her.

For a little while, my niece was keeping me updated. Even then, we didn’t dare speak of Saule directly. Speaking in code, my niece had told me my daughter was working as part of the camp system, possibly as a teacher. But I’ve lost contact with my niece. It’s been three or four months since we’ve spoken.

Now, after months without news, I just recently got a letter from my daughter’s colleague. Their firm had become concerned with her case. They managed to send a colleague to the camp to speak with her. In the letter, my daughter told her colleague she felt completely brainwashed. She said she felt like she had been born in that place, like she’d spent her whole life in the camp. She said she could barely remember her family. The colleague’s letter was sent to me here in Kazakhstan, and included another new piece of information: if I returned to China, my daughter would be released.

Why do they care about me? I’ve heard each village has to meet a quota of how many people are sent to each political camp. Most people are taken into the camps for religious knowledge or for having relatives in Kazakhstan. I fall into both categories. I imagine I’d be useful for filling those quotas. And not only was I an imam, I overstayed my visa by a year. I was supposed to go back to China one month after I came to Kazakhstan. I violated the terms of my visa. If I go back, I’ll be put on trial. When my daughter’s firm inquired at the camp to ask why she was being detained, they received the following reply: it’s not about her; it’s about her father.

—Kulzhabek Nurdangazyluly, 46 (Saule Kulzhabekkyzy, daughter)

Interviewed August 2018

THEN I’LL ASK, HOW IS THE WEATHER?

Magira is the oldest of three children. Her mother died a month before the family immigrated to Kazakhstan. Her father later remarried, but the stepmother is afraid to look for him. The task falls to Magira.

We don’t have anything left in China. We gave up our land, our animals, everything to come to Kazakhstan. We came legally, thanks to the migration legislation passed after the fall of the Soviet Union. It was 1992. I was ten years old. Eventually I became a citizen, and so did the rest of my family, with one exception. My father remained a Chinese citizen, a requirement for receiving his pension.

In 2000, my father got sick. They couldn’t diagnose his sickness here. They even said he would die soon, that it was hopeless, and they discharged him from the hospital. But he went to a hospital in Ghulja, in China, and in three days they diagnosed him. He was treated there for a month. He got well. Afterward, he traveled to China twice a year, in the spring and fall, for continuing treatments. He felt it was keeping him alive. Each year, he spent his whole pension on these treatments.

The last time he crossed the border was on October 22, 2017. A week later, he called me. They’ve taken away my passport, he said. Please don’t call. I’ll call you myself. At the time, he said they promised to give his documents back in a week or two, but they didn’t. Still, he called every month to update us. Then, in March, he broke his leg. He became crippled. He still couldn’t get a response from the local police. We couldn’t talk openly on the phone. Let’s not discuss it, he said. We pleaded with him. Why don’t you tell them you don’t want the pension anymore? Tell them you just want to come home. Please, he says, not on the phone.

He now lives in his brother’s place in Shegirbulak. It’s a hard place, the security is strict, and his leg isn’t getting better. It’s so hard to communicate—we worry that everything is being listened to. We can’t talk with him directly. I call my cousin’s sister in Ürümqi on WeChat. She calls her parents. They talk to him. That’s how he gets news to us. For almost a year, we haven’t heard his voice. Communication with her is easier, more frequent, because Ürümqi is a more liberal city.

Just to be safe, though, we always use codes to talk to each other. I might ask my cousin’s sister, Do you have any news? Meaning about my father. Then I’ll ask, How is the weather? This is how I ask about my father’s condition. If the weather is calm and good, so is he. If it’s cold or hot, windy or rainy, his condition is poor. We’re careful. We never say the word China. We never say Allah kalasa1. We don’t use any religious phrases. But we can communicate events using this code. It’s how all of us talk with our relatives in China. Everyone knows about it. For example, I know that my father went to the police two months ago. He told them he needed to treat his leg. He needed his passport back. They couldn’t help him. They sent him away.

Last week my cousin’s sister visited Shegirbulak for a friend’s wedding. While she was there, she made a video call to us on WeChat. It was the first time we’d actually seen him since he went to China last year. I took a screenshot. Look at how old he is. See those crutches leaning against the wall? He needs them to walk. His leg has gotten worse. I want him to visit the consulate in Ürümqi, but he can’t walk. No one will help him. Everyone in the village is for himself. They’re afraid. If you help someone with connections to Kazakhstan, you can get in trouble. So nothing is happening. I spoke with my cousin’s sister just the other day. The last report went like this: No news, no change in the weather—it’s calm.

—Magira Toktar, 36 (Toktar Sanasbek, father)

Interviewed August 2018

IT WAS IN SOME MOUNTAINOUS PLACE

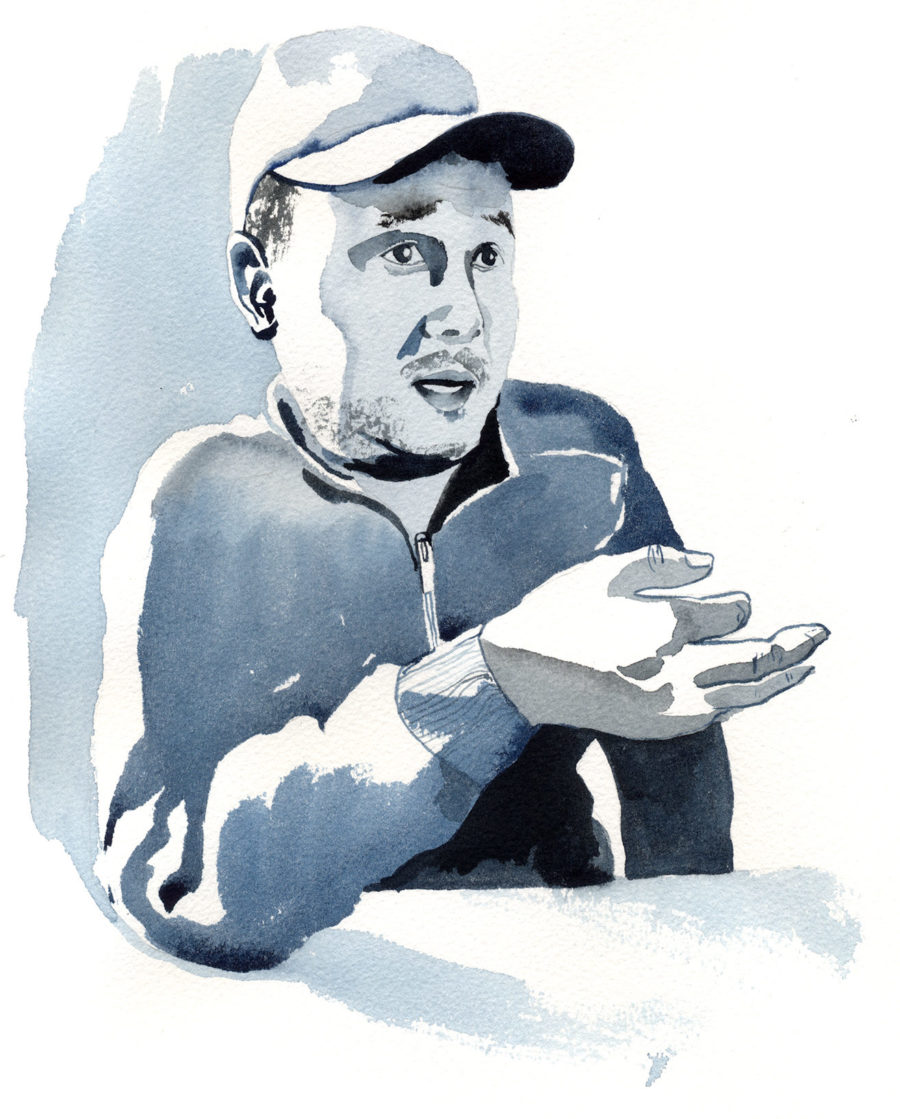

Zharkynbek was in a camp for eight months. His escape still seems to surprise him. “I thought they were going to dangle my freedom in front of me forever,” he says.

It was in some mountainous place. We drove out in a windowless van with a metal grate inside. I couldn’t see anything. Before, at the police station, they’d given me a medical exam. They’d taken a blood sample. I couldn’t understand what my sentence was—what I’d done wrong.

I was born in Ghulja in 1987. I came to Kazakhstan when I was twenty-four. The next year I got married to a local girl. For five years I worked as a line cook in a café. I had a residence permit, but my Chinese passport was about to expire, so I went to the consulate. They told me I had to go back to China to replace it. I crossed the border in January 2017. At the crossing at Khorgos, I was detained. They took all my documents and took my bags. They interrogated me, checked my phone. You know, WhatsApp is illegal in China, they told me. At some point, they asked about my religion, and I told them I prayed five times a day. I told them I was a practicing Muslim.

They took me to Ghulja. There the police interrogated me again. The same questions, but this time they beat me. You’ve been to a Muslim state, they said. Why didn’t you take their citizenship? Why are you here? After beating me, they brought me a piece of paper to sign and put my thumbprint on it. Then they took me to the camp.

At the camp, they took our clothing away. They gave us a camp uniform and administered a shot they said was to protect us against the flu and AIDS. I don’t know if it’s true, but it hurt for a few days.

I was taken to a room equipped with a security camera and twelve or fifteen low beds. There was a toilet in the corner. For eight months, I lived in this camp, although not always in this room. They moved us from room to room roughly every month, seemingly at random. All the rooms were similar to the first. I began to realize it was a huge building—it seemed endless. Once a week we were made to clean some part of it, scrubbing and sweeping. That’s how I learned that all around the building stood a high fence and that every corner had a camera stuck into it.

They had strict rules. This is not your home, the guards would tell us. Don’t laugh or make jokes, don’t cry, don’t speak with one another. Don’t gather in groups. The guards came from every background. There were Kazakh and Uighur guards, but the Chinese guards were the ones who would beat you. They told me just what the police had told me. You’ve been to a foreign country, they said. Your ideology is wrong.

We had Chinese-language lessons. We learned the Chinese anthem and other official songs. We learned Xi Jinping’s policies. I couldn’t speak Chinese and I can’t say I learned anything from the classes. If their purpose was to teach us Chinese, why did they have so many old people in the camp? How could they learn Chinese? What I gathered from those classes was that they just wanted to erase us as a nation, erase our identity, turn us into Chinese people.

It was cold. The whole time it was cold. I’ve got health problems now because of it. I was disciplined more than once. My second night at the camp, I turned off the lights in the room so that we could sleep. It was against the rules to turn off the lights, even at night, but I didn’t know that. So in the middle of the night they burst into the room. I admitted that I was the one who had turned them off. We don’t switch off the lights, they said. Don’t you know the rules? And they beat me with wooden batons, five or six blows on my back. You could be punished for anything: for eating too slowly, for taking too long on the toilet. They would beat us. They would shout at us. So we always kept our heads down.

Since we couldn’t talk to one another, we shared notes in class. I got to know five others in class with me in this way, all of whom came from Kazakhstan. We became good friends. Like me, they’d been detained for having WhatsApp, or else for holding so-called dual citizenship in China and Kazakhstan. I have no idea what happened to any of them.

I tried to behave well in the camp. I understood that because I had relatives in Kazakhstan, I was likely to get out sooner. I saw it happen to others. Even when I was at the camp, although I didn’t know it, my wife was complaining. I don’t think they would have let me out of the camp without those complaints. She was publicizing my case, and in August, after eight months in the camp, they released me to my parents.

The police drove me to their house around midnight. Early the next morning, officials came by. Don’t go out, they said, and don’t let us see you so much as holding a phone in your hands. You have no documents, they said, so you can’t leave the house. They had a reason for everything. It was never their fault, never their decision. It was always due to some rule.

All the while my wife was working to publicize my case. One day the police came and said, It turns out you have a wife in Kazakhstan. She is complaining. We’ll get a WeChat for you. And just like that, they let us talk on the phone. Of course, we cried at seeing each other. It turned out my wife had been filing endless complaints and petitions while I’d been in the camp, and uploading videos to YouTube. The police asked me to tell my wife to stop complaining. They wanted me to convince my wife to come to China with our son. I suggested to them that they should just let me go. You’re a Chinese citizen, they said. You should stay here. I replied that I had a wife and son in Kazakhstan. Well, they replied, this is none of our business.

The officials were always present in the room when I called, so I did as they said. I told her to stop complaining and suggested she come to China. But she refused. I won’t stop, she said, not even if they put you back in prison. I won’t stop until you’re home. The policemen wrote down all my information, and after three days they called to say they were going to let me return to Kazakhstan. They promised they would send my passport as long as I swore not to tell anyone in Kazakhstan about the camps. They made me sign a pledge not to disclose any information about “internal developments” in China, and to return to China once I’d visited my wife and son. I had to sign it to get my passport, but still they wouldn’t give it to me. Your passport is ready, they said, but your wife will not stop complaining! Didn’t you tell her we were going to send you back? Every step was a struggle.

Even when I finally got my passport, even with a plane ticket my wife had bought in my hand, I still found I couldn’t leave. I’d traveled to Ürümqi. At midnight, I was at the airport, ready to board. As I was about to get on the plane, they stopped me. We have a notice here that your local police force didn’t authorize your exit from the country. So they called the local police, who said I’d forgotten to sign some form. I threw my passport at the airline employee. I threw all my documents onto the desk. I have the visa, I said. I have the passport. Why don’t you let me go?

I had to go back to my village. I called my wife and she started another campaign. She contacted the embassy. Within fifteen minutes of her making that call, I got a call from local police. They returned my passport again and told me I was free to leave as long as I told them when I was planning to leave the country. I took my passport but didn’t tell them anything. Instead, I went straight to Khorgos. When I reached Khorgos, I got a call on my cell phone. It was the village police, asking where I was. I’m at my nephew’s, I said. I’ll come to you straightaway. I was already at the border, inside the free-trade zone. I took the last minivan of the day to the Kazakh side of the border. The border guards asked my destination. Kazakhstan, I said. Did you get permission from the police? Yes, I said, and held my breath. As soon as I crossed the border, I took the SIM card from my phone and threw it away. I bought a new SIM card and called my wife. I’m here, I said.

And now I’m home, but my health—to put it simply, I don’t have health. For the past five months, I’ve been tired. All the time. I lose my memory. Sometimes I can’t remember anything, and—I’ll be frank—I’m impotent. I went to the doctor and they found microbes in my blood.

All through my detention, I tried to have patience. I told myself that everything that was happening was a test—that I should endure it. When I looked around the camp at my Muslim brothers, at my Kazakh, Uighur, and Dungan brothers, I saw that this was an attempt to divide and destroy our identity: a tool of Chinesification. I don’t think they were ever planning to let me go.

—Zharkynbek Otan, 32

Interviewed May 2019

Losing a loved one inside Xinjiang seems as likely to happen to men as to women, to the young as to the old, to farmers and pensioners as to artists and schoolteachers. At seventy-nine, Abylay Mamyrzhan, a retired herder, is the oldest emigré from Xinjiang I meet. The youngest, Akzhol Rahman, is sixteen. He is trying to find his father, Rahman Rahymbay, a retired middle school teacher who was sentenced to nine months in a “political learning camp,” and who disappeared in China following his release.

Akzhol is wearing a new flannel shirt and his hair is freshly cut. He is in tenth grade, and is shy but determined. “We can’t get any news directly,” he says. “None of our relatives are left in China. So whose house is he living in? How is he?”

WE TRUSTED WHAT THE OFFICIALS TOLD US

That’s my family in the pictures. My wife and our three children. It’s been two and a half years.

Here, this is our daughter Ulnur. She’s thirteen. She likes—I remember—she likes painting. She did well in school painting this and that.

This is my daughter Gulnur, born in 2008. She was talented in mathematics. I remember when she was in second grade, she was solving equations easily without a calculator. They were good sisters, the two of them. They got along.

Their brother, Yernur, was born in 2010. He was seven when he left for China with his mother. He’s started school now.

In 2014, three of us came to Kazakhstan together: my young wife and our youngest kid, our son. My two daughters didn’t have passports. Passports aren’t normally issued to school-age children where we lived. There’s a long process to get them. Our daughters stayed behind with my wife’s parents while we made arrangements to bring them to Kazakhstan. We visited them often in China. My wife kept her Chinese citizenship so that it would be easy for her to work on bringing our daughters to us.

The authorities called my wife’s parents in February 2017 and told them to inform us that we could now apply for our daughters’ passports. My wife went to China with our son. Our daughters did get their passports, in fact. But the authorities took them away almost as soon as they were issued. And they took my wife’s and my son’s passports as well. We’ll check your documents, they said. In a week’s time, we will give them back to you. Maybe she should have left then, with all our children, without telling anyone, in those first five days when they still had their documents. But we trusted what the officials told us.

In the days that followed, my wife went to the police station three times. On her third visit, they reprimanded her. If you come one more time, they said, we’ll send you to political study. Now even if I tell her to go, she refuses. It’s been two and a half years. They’re living with my parents. My oldest daughter, Ulnur, is no longer there. The authorities put her in a student dorm in a boarding school. They’re doing it all over the region in order to divide minority students among many schools. There are too many Kazakhs where my parents live. She comes home only on the weekends. Even if she’s sick during the week, she can’t come home; she can’t call anyone. In the fall, the same will happen to Gulnur. She’ll be taken to a boarding school somewhere.

As for my wife, she’s been made a guard at a bank. They trained her and gave her a uniform. Otherwise I don’t know the details of their lives. My wife won’t say. She’s afraid, most likely. She won’t even tell me what she makes. Probably she works for free. She kept her Chinese citizenship only to make it possible to help our daughters. We never thought it would become impossible to leave.

—Oralbek Kali, 35 (Gulzira Ramazan, wife; Ulnur Oralbek, daughter; Gulnur Oralbek, daughter; and Yernur Oralbek, son)

Interviewed May 2019

SHE DIDN’T READ NAMAZ

Shalkar hasn’t been to China since his parents brought him across the border, in 2003. But many of his relatives are there. He shows me appeals he has written to the European Court of Human Rights and the Kazakhstan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nothing has worked.

In Kazakh we say “sister,” not “aunt.” The truth is, she really is a sister to me. We’re separated in age by only a few years. We used to talk on the phone every month, just to say hello.

In 2017, they started to take Uighurs and Kazakhs from their villages. I don’t know why. My aunt spent three months in a camp. After three months, she was placed in a prison. No one knew this at the time. It was only a few months ago that I heard from one of our relatives that she had been convicted and sentenced. Without any reason, without any guilt. This January, I started writing petitions and complaints here in Kazakhstan. I gave interviews and I posted videos online. The next month, her husband was called by the local authorities. They told him to get in touch with me to tell me not to complain.

At the time, her husband didn’t even know what had happened to his wife. He was in the dark. When they called him, he learned that she was being held in a women’s prison in Ghulja. She had been sentenced to thirteen years.

I don’t know why she was sentenced. I heard it was for religious reasons, so probably she visited an imam at some point. But she wasn’t such an observant Muslim. She didn’t read namaz2. And her husband wasn’t sent to a camp. I don’t know why. He’s left alone to take care of their daughter, so maybe that’s the reason. But why her? My aunt worked as a housewife. She didn’t have any education. She was just an ordinary person.

—Shalkar Bakyt, 27 (Gulzia Nurbek, aunt)

Interviewed May 2019

ONLY THEN DID WE START TO LIVE DECENTLY

One wall of Atajurt’s office is covered with photographs of the known missing: hundreds of faces, maybe a thousand. Khalida, a small, persistent woman in her sixties, pulls me over to a corner to show me her family members. “Here,” she says. “And here, and here, and here, and here…”

A small hamlet called Karagash is where I was born, in Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. A pasture for cattle. My mother died when I was two years old. I heard my father was a party activist, but—let me be frank—I never knew him. After my mother died, my father remarried and forgot all about me. I was sent to live with my mother’s relatives. I lived with them until I was five. Then they didn’t want me either. I lived here and there, with people who knew my mother and took pity on me. An orphan. I’m illiterate, to tell you the truth. There was no one to support my education.

In 1975, when I was twenty-one, I met my husband. He was an orphan like me. His relatives had moved to China during the famine, before he was born. When they moved back to Kazakhstan, he was left behind without anyone. His name was Rakhymbergen Kittybay. He died last year, on September 9.

I was pregnant eight times. My first four pregnancies, including one set of twins, were unsuccessful. Four sons, one daughter—I lost my first five children. Then my son was born. Among Kazakhs, when you have miscarriages, or when babies die one after another, a new child’s life is understood to hang by a thread. So when my son was born, we gave him immediately to our neighbor. The neighbor kept him and fed him for the first week of his life. We refused to see him at all. Then we bought our baby back. We brought presents, clothes, firewood. We passed the presents through our neighbor’s door and took the child back through the window. It worked. After that, I had more children and they all lived. But until our firstborn son was twelve, my husband held him like this—like an egg. He was always hanging on his father’s neck, even when eating. We were so afraid to lose him.

They were difficult times, those early years of our marriage. I would have my son strapped to my back all day while I worked, cutting cornstalks, threshing wheat. My husband did the same. We were sharecroppers. It was backbreaking work. When we had our second child, I would tie them both to a post in the field like sheep so they wouldn’t wander off.

In the ’90s, the state allocated some land to us. Only then did we start to live decently. For the first time in our lives, we didn’t go to bed hungry. We planted wheat, corn, soy, sometimes beets for sugar. Our own crops, on our own land. After the border opened, my husband went to Kazakhstan to try to find his family. He managed to find his mother. His father had already died. From then on, he stayed in Kazakhstan to look after her. He would come to China to visit for five or six days at a time, then go back. I was raising my sons alone. His mother didn’t die until 2007, at the age of 103.

After my first son who lived, I had three more sons all in a row. The three eldest all work together in construction, building houses from the ground up. The fourth was still a boy when we moved to Kazakhstan, but the elder three all made lives for themselves in Xinjiang. All of them married. In fact, all of them found Uighur wives. It’s true we lived in an area of mostly Uighurs, but there was another reason: We were poor. We had no savings. When you marry a Kazakh girl, you have to pay a dowry. We couldn’t afford it. Uighurs don’t have dowries. So one by one they stole their Uighur wives and we didn’t pay a penny. We bought only their clothes.

When they started arresting people, my three eldest sons were taken first. They took all three on the same day, last February. They lived together in the same village in Kunes. The wife of my second eldest son called me to say they’d been arrested. The next day, she called me again. Mama, she said, they took my sister. Your daughter-in-law. They took Toktygul. They had arrested my eldest son’s wife. But I don’t know [breaks down crying] what happened to my grandchildren. They had five children. I don’t know where they are.

On hearing the news, my husband came down with a migraine. The next day, when our daughter was taken, it got worse. But we decided to wait and see. I told him to hold out. When we hadn’t heard anything by the end of the month, I called the administrator of Karagash, a man by the name of Nurlybek. I asked Nurlybek what had happened to my sons. Where are they? Where is my daughter-in-law? They’re being reeducated, Nurlybek said. He told me my other two daughters-in-law had also been taken to the reeducation camp. They, too, were being reeducated. Political studies was how he described it. I have fourteen grandchildren in China. Some are very young. I asked Nurlybek where they were. Where are my fourteen grandchildren? They are all studying, he said, and hung up.

After that, my husband could no longer walk. He lay in bed. From the end of February, he never walked again. I took care of him. I couldn’t go anywhere, couldn’t leave the house. He got weaker and weaker. Months went by. We didn’t tell anyone what had happened to our family. Then, on September 9, 2018, he had a bout of strength and shouted all his sons’ names: Satybaldy! Orazzhan! Akhmetzhan! He turned to me. I am entrusting my sons first to Allah, then to you, he said. As for me, I am finished. He died later that day, at 5:00 p.m.

After he died, I spent ten days at home. I didn’t say a word to anyone. Then I decided to find my children. I came to Atajurt and met with Serikzhan. Others wrote letters for me because I can’t write. The letters explain that my children are gone, and that my husband couldn’t stand to see his sons and daughters taken away. That it had killed him.

Only my youngest son is here in Kazakhstan with me. But even he’s married now, and their apartment is too small for me. I live alone, and I don’t have a pension here, so I have to work. My youngest son helps. He goes in together with a dozen other people to hire a truck to bring vegetables out of China. I take my share and resell them at the bazaar. Cabbage, cucumbers, tomatoes, lettuce greens. I can’t afford a stall. I sit on the street with my carrots and cabbages. But my youngest son is good. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke. He used to drink before, but he gave it up. He has a family to take care of.

—Khalida Akytkankyzy, 64 (Rakhymbergen Kuttybay, husband; Satybaldy Rakhymbergen, son; Toktygul Mametzhankyzy, daughter-in-law; Orazzhan Rakhymbergen, son; Sharapat [surname unknown], daughter-in-law; Akhmetzhan Rakhymbergen, son; Miray [surname unknown], daughter-in-law; and fourteen grandchildren)

Interviewed April 2019

Nurmylan is wearing an orange vest with yellow polka dots. He sits in his grandmother’s lap, whacking her phone against the desk. “For the first time in two years, just the day before yesterday, we got a video call from our daughter-in-law,” the grandmother, Gulzhanat Baisyan, says. Her daughter-in-law, Adiba Kairat, had called and asked to see her three-year-old son. Gulzhanat had turned the phone camera to Nurmylan. “She cried,” Gulzhanat says. “We were all crying.”

Adiba vanished into China two years ago. She had taken her two daughters, Ansila and Nursila, and left Nurmylan, who had just turned one, with his grandparents. It was meant to be a short trip. Adiba was going to visit her parents. The authorities took her passport and put her in a camp for a year. Now she is working in a factory somewhere, and the two daughters have been left with distant relatives in the village. No one watches them closely. Once, they caught lice. Gulzhanat places a photograph on the desk between us. She received the photo from Adiba’s relatives. The girls in the photo are bald and very thin.

“I think they let her call us so that she would tell us to stay quiet,” Gulzhanat says. “She just kept saying, ‘Our situation is good. Please don’t complain.’ We’d been talking to reporters, posting videos online. I think she was being forced to say this. I didn’t play along. I told her to come home. I told her we couldn’t care for her son by ourselves. She was just crying. She didn’t reply. ‘Do not complain,’ she finally said. ‘It will not do me any good.’”

AT NIGHT, THEY UNCUFFED MY ARMS BUT NOT MY LEGS

A café, empty and closed. Orynbek pauses often to make sure no one is listening behind the door.

I don’t want to spend a long time talking to you.

I was born in 1980 in a village in the district of Chuguchak. That’s the old Mongolian name; the Chinese call it Tacheng. It’s in the mountains that cross into Kazakhstan. Until 2009, there was a border crossing near my village, but I never used it. Until I was twenty-four years old, I never left home. I helped my father in his pasture. We raised sheep and cows. I didn’t get much schooling.

I first came to Kazakhstan in 2004, just to see the country. My younger brother was studying in the arts school in Almaty. He wanted to become an actor. I liked it here, and the next year I decided to come back for good. It was easy back then to cross the border. Kazakhstan was encouraging oralman3 to move, part of its repopulation efforts. I came back, renounced my Chinese citizenship, and became a citizen of Kazakhstan.

In 2016, my father died. He was one of twelve children. [Takes an old passport photo of his father from his wallet and places it on the table.] Most lived in China, but he had two siblings here, my uncles. I decided to go with them to China to the zhetisi, the ceremony that takes place on the seventh day after a funeral, to reunite with his other siblings. The crossing was easy. I saw my relatives at the banquet. We ate lamb and horse. After the ceremony, I came back to Kazakhstan. I had no trouble.

A year passed. In November 2017, I decided to go to China again. My father’s funeral had put me in mind of old friends from my village. I wanted to see some of the people I hadn’t managed to see at the ceremony. This time was different. At the border, I was stopped. They explained that my records of having left China were gone. An official from the Chinese government, an ethnic Kazakh, explained that this was a serious issue. He asked for a document explaining the absence of this document. Well, I didn’t have one. So they took my passport. They told me I was holding dual citizenship. This is a crime in China, they said. I didn’t have the paper in my records that confirmed I’d renounced my citizenship. They said they didn’t have any records at all.

After a long time, maybe twenty-four hours, I was allowed to enter China. I was shaken up by the encounter. I thought that I should probably go directly back to Kazakhstan, but I couldn’t. They had taken my passport and told me they would see about my case. As I was leaving, the interrogator took me aside. If anyone asks why you came to China, he told me, tell them you wanted to settle your registration and check on your citizenship status. Whatever you do, don’t tell anyone that you were trying to visit family or friends. I don’t know if he was trying to help me or deceive me—I couldn’t understand any of it—but later on, I took his advice.

I went to my hometown and stayed with my relatives. The village was unrecognizable. My own family was afraid even to talk to me. It was nothing like the year before. Every day, local authorities would come by and explain to me that I couldn’t leave China until I presented this paper renouncing my citizenship, which I’d been told I would receive soon. One day they asked me to sign a document. They said if I signed it, they would restore my registration, cancel it officially, and I could go back to Kazakhstan. So I signed.

After some weeks, on December 15, the ethnic Kazakh interrogator from the border came to see me. He was accompanied by three Han Chinese men. They said my paperwork had gone through. They were going to take me to the border. But first, they said, you need to be examined by a doctor.

They drove me to a large office building. It was shiny like a hospital and everyone was wearing white medical clothing. But it was also somehow different from a hospital—I couldn’t tell you exactly how. We went from room to room for different examinations. There were several doctors, male and female, and they checked all over my body, from head to toe, the women as well as the men. I don’t speak Chinese. I couldn’t understand what people were saying. I wanted to resist, but I was afraid.

We finally left the facility that wasn’t a hospital, and they drove me to a multistory building surrounded by walls and barbed wire. It looked like a prison. I knew we were in the middle of Chuguchak somewhere, but I didn’t know more than that. When I saw the building, something took place inside of me. I didn’t believe they were taking me to the border. I took my phone out of my pocket and tried to make a call—I don’t even know who I was going to call—but they saw what I was doing and took my phone away. As we entered the building, they told me simply that I had to go through a check-in process here. Afterward, they said, you will be set free. They asked for my shirt. Then my pants. I was left in my underwear.

I was angry and afraid. I didn’t know what to think. I asked them: Should I stay here in my underwear? Without any clothes? They brought me some clothes—camp clothes. I dressed, and as I dressed I kept shouting at them: What are you doing to me? I am a Kazakh citizen! They cuffed my hands behind my back and cuffed my legs together. I said I hadn’t committed any crime. Prove that I committed a crime, I said.

They put me in a room with eight or nine other people, all Uighur or Dungan.4 I couldn’t understand any of them; I don’t speak their languages. There was a single table, a sink, a toilet, a metal door, and several small plastic chairs, the kind of chairs you see in schools, for children. Above the door was a camera. I came to know this room well. For the next week, I didn’t leave it. During the day, I sat in a chair, my arms and legs cuffed together. At night, they uncuffed my arms but not my legs. My legs were always cuffed, with just enough chain to move them if I had to walk, although I wasn’t allowed to walk except in the morning, to wash myself at the sink. I wouldn’t have been able to run if I’d tried. Seven days and nights passed like that.

The other men in the room avoided me. They seemed afraid of me. I don’t know why. But I was the only one whose arms and legs were restrained. The rest of them were free. Every day they left to go somewhere, while I stayed behind. I wasn’t allowed to move from the chair where I was sitting. In the morning I washed my face, but otherwise there was no bathing. I was alone all day. And no one, or almost no one, talked to me.

On the morning of the seventh day, two people came and took me away. We went to a new room, much like the first. We were alone. One of the interrogators was either Kazakh or Uighur; the other was Chinese. The first asked whether I knew why I was there. First of all, he said, you’ve been using dual citizenship, and that’s a crime. Second, you are a traitor. And third, you have a debt in China.

None of it was true. I told them I don’t have dual citizenship. I’m a Kazakh citizen. What’s more, I told them, I don’t have any debts in China. I left a long time ago. I don’t owe China anything and China doesn’t owe me anything. I repeated what the man at the border had advised me to say, that I came only to check on my registration status. I don’t know why I’m here, I told them. I didn’t commit any crime. I asked them to prove to me that I committed a crime.

He told me not to ask questions. We ask the questions, he said. Then the real interrogation began. Tell us who you communicated with in Kazakhstan. What did you do? Do you pray? Do you uphold the Islamic rules? How many times a day do you pray? I told them the truth: I don’t practice Islam, I don’t read the Koran, I don’t have much education. I herd cattle. I’ll tell you what I told them, which is that I didn’t have schooling. I spent two years in first grade and then graduated second grade, and that was it. I was helping my father in the winter and summer pastures after that. My father gave me my education, and that’s what I told them. If you look at the records, I said, you’ll see that I’m telling the truth. But they didn’t believe me. Uneducated people don’t go to Kazakhstan, he said.

Then they asked me all about my property, my cattle. I told them my home address in Kazakhstan. I told them that I was married in 2008 and divorced in 2009, that I had no kids. I told them everything I could think of, my whole life story. I answered all of their questions. But they kept telling me I was a traitor.

They took me into the yard outside the building. It was December and cold. There was a hole in the yard. It was taller than a man. If you don’t understand, they said, we’ll make you understand. Then they put me in the hole. They brought a bucket of cold water and poured it on me. They had cuffed my hands and now told me to raise my hands over my head. But it was a narrow hole and I couldn’t move inside. I couldn’t raise my hands. Somehow, I lost consciousness.

When I woke up, I was back in my room. There was a Kazakh guy beside me. I’d never seen him before. He said, If you want to stay healthy, admit everything.

I slept, I don’t know for how long. When I woke up again, there were two new prisoners. One was Kazakh, like me. He told me he had been detained for traveling to Kazakhstan. He’d gone to visit his wife and child. But I couldn’t find them, he said. The other guy was Dungan. He didn’t speak Kazakh. But the Kazakh guy told me that his mother had died, and that he’d organized a funeral in his village according to Islamic traditions. The police had accused him of being a Wahhabi and had taken him away. I still felt poorly from the hole, where I was told I’d spent the whole morning unconscious. Afterward, I had a fever. But the two Muslim guys—the Kazakh and the Dungan—helped me to recover. They watched over me.

Time passed, and people came and went from the cell all the time. All told, I spent thirty days in that room, including the week before the hole. Every day the men went out and I stayed behind in the cell, although now I had the Kazakh and the Dungan to keep me company. Every few days, four or five men would be moved out and new men would arrive. I remember a guy named Yerbakit, who had permanent residence in Kazakhstan but held Chinese citizenship. There was also Shunkyr, a professional athlete who had never visited Kazakhstan. A third man was called Bakbek. We didn’t talk much. I didn’t want them to get in trouble for talking to me. We didn’t say words like Allah. We never said Salaam aleichum. We were afraid.

Every Sunday our cell was searched. We all had to kneel and put our hands on top of our heads and look down as they tore the cell apart. We could see the guards’ pistols right at eye level. I don’t know what they were looking for. We would joke with one another that we should probably produce whatever it was we’d stolen, so that the searches would stop.

One day they took us all out and cut all our hair. Shaved our heads.

Once I asked my cellmates where they went every day. At first, nobody wanted to say. Then Yerbakit told me they were being taken to political classes. He said they learned Chinese sayings and songs by heart. Not long after that, one of our guards gave me some papers with three Chinese songs to learn myself. The words were in Chinese. I told them I couldn’t read Chinese, and they took the papers away. They gave me a notebook in which someone had written the songs in Kazakh script,5 and they told me to learn them by sound. One of the songs was an anthem. They told me it was the Chinese national anthem. The second was a song describing the current policy pursued by the Chinese leadership, an educational song. I never found out what the third song meant. We all had to learn them. The Dungan guy spoke Chinese and learned the songs quickly, but my Kazakh friend and I had a harder time. We used to cry together. We would hug each other and cry, and try to learn the songs by heart. I believe I will never forget those thirty days.

In mid-January, my two cellmates and I were finally allowed to attend classes with the others. We were placed in classes according to our level. Because I wasn’t educated, I was in a low level, with many women. It wasn’t just men in the camp; there were eighty or ninety women there, living separately. It was a big building, although I can’t tell you how big it was. They would count us off room by room, but never all together. They counted in the morning and the evening, the way you count your animals in the pasture. I remember on the third day I went to class, I found they had cut the women’s hair. They didn’t shave their heads like they did the men’s, but they cut their hair above their ears.

Of course, all the time I attended classes, I didn’t know what I was doing there. I discussed it again and again with my teachers. They said I was to study for a year and a half, but if I was unsuccessful, I would remain there in the camp for five years. I felt I would rather die. On several occasions, I contemplated suicide. Once, I even tried to strangle myself with a shirt in my room, but because there was a camera in the cell the guards came in and stopped me.

While in class, we could write letters to one another. I happened to know one girl, Anar, from my childhood village. At first, she pretended not to know me. There were two other women from my village in the camp who did the same. Then I wrote her a letter. Please forgive me, she wrote back. Of course I know you, but I said I didn’t. I was afraid. Why are you here?

Anar shared a bedroom with another girl, Ainur. The three of us would write letters and throw them to one another under the table during class. We talked through those letters. We made an entire world. In one letter I wrote about my feelings for this girl, Anar. Affectionate letters, you know. But at the end of February I was transferred to another prison. I never saw those girls again, and I haven’t heard anything about what’s happened to them.

Tell me again why you’re asking all of this. Who are you? I believe there are Chinese spies in Kazakhstan. When I was released, they told me: If you tell this story to anyone, you’ll be imprisoned again in China. I am doing this for my people, in the name of my Kazakh people. I’m the only one I know from my part of Xinjiang who has been released. The only one. And if I go back to prison, I won’t be sorry. My only crime in going to China was being a Kazakh. My second crime is that I’m telling the truth.

I don’t know if it’s any use telling you all this.

One day, seven of us were transferred. We were handcuffed and taken to the yard and told we were being taken to another camp. They searched us and cuffed every two people together and put us in a car. As we drove, I had the idea that we were being sentenced to death. Our heads were covered. I thought they were going to kill us. Instead, they only took us to another cell. It turned out to be a former military camp. We sat in more political classes, and my teachers again told me I would stay in this camp until I’d learned Mandarin Chinese. They told me to prepare to study for a year and a half. I was sometimes beaten in this second prison. I was asked to tell them things I didn’t understand. I thought I might be inside for the full five years.

Five days before my release, my interrogations became more frequent. Some lasted through the night into the early morning. During these interrogations, they asked only one question: Why did you come to China? They made me sign papers that they said would determine my fate—whether I would go back to Kazakhstan or remain in China—but I couldn’t understand what I was signing.

One day before my release, they sat me down and showed me photos of my relatives. They asked if I knew any of these people. At first I said no. I was afraid. We will make you remember them, they said. So I told them who they were: My mother, my cousin, my brother, and my father. Even my father was there, although he was dead.

When I saw these photos, I despaired. I thought my family had all been detained. The photos looked just like my own prisoner photos. [Removes from his wallet an ID card with a photo in which his head is shaved, along with two unlaminated versions of the same photograph, and places them next to the photograph of his father.] I didn’t know how else they could have gotten photographs of them all. I couldn’t understand it. My father died in 2016; my mother lives in Urzhar, in Kazakhstan. How did they have these photos of them? My first thought was that somehow they were all in the prison with me. All of my relatives from Kazakhstan, every one.

They waited while I identified each of my relatives. When I got to my father, they tore the photo in half and threw both halves in the dustbin. I cried that night until morning, thinking of my relatives somewhere in the prison, and not understanding anything that was going on.

The next day, they took me to the yard without warning. You will not take your notebook with you, they said—this notebook had all the contacts I’d made in prison—and you will not be able to say goodbye to your friends. They brought me to my cell. When I got there, I saw a prisoner I knew, Arman. He was from Astana. There was a sense of joy in the room. He was being released too. But I didn’t say anything to anyone. Arman and I were cuffed together and taken away by car. It was springtime. They drove us to the border.

Later, I counted the days of my detention: 125 days. Before they set us free, they made us commit ourselves to silence. If you say anything, they said, you will go to prison, even if you’re in Kazakhstan. I believed them at the time. I signed different papers that were placed before me. I was made to recite a pledge to Allah that I would not talk about what happened to me.

I believe that Allah will forgive me this oath I made in his name.

They drove us to the border. So now I’m here in Kazakhstan. And I’m tired.

Now I want you to write the truth without adding any lies.

—Orynbek Koksebek, 38

Interviewed August 2018

Abylay Mamyrzhan has a goatish white beard and wet blue eyes. “My father was born in Xinjiang in 1906,” he says. “We were nomads. We used to herd our cattle like our ancestors did, moving from place to place.”

Abylay can still remember the early days of the Cultural Revolution. His father had been forced to give up their livestock to a collective farm. The Chinese Communist Party had wanted all the nomads where he lived to sedenterize. His family lost their long-standing grazing rights and all their accumulated animal wealth. As a teenager, Abylay was forced to wear a gaomao—a high paper hat that identified him as an enemy of the people—to community meetings. His homeland was lost to him. People were starving to death in the fields. “Everything there was taken from us,” he says.

In the 1990s, the government allotted his family some land. “The forest was untouched. It was bountiful, with coal and gold deposits. Now I don’t know what’s happened to it. We’re supposed to get compensation, but I suppose the local officials are using it for their own benefit.” He wants to see his land again but feels it is impossible. “If I go, I’ll be detained,” he says. His relatives can’t tell him anything. “What happened in Mao’s time is happening again.”

EATING WITH THE STUDENTS AND SLEEPING IN THE CLASSROOMS AT NIGHT

ZHEMISGUL: I’m a hairdresser in Taldy-Kurgan. Makeup, hair, skincare.

SUNGKAR: I’m in college in Almaty. I’m a philosophy student. But I was still a schoolboy when our parents went to China. It was March 2017. I was in eleventh grade. Our family had some land that had been given to us by the government. My parents farmed melons, corn, and wheat there. When we left for Kazakhstan, we rented it out. Within a month of our parents’ arrival, the local authorities took their passports and told them they had to give up their land for good. My parents went to speak with our renter. He was supposed to sign a paper agreeing that my parents were giving up the land so that they could return to Kazakhstan. But he wouldn’t sign it. He said he was worried about what would happen to the land after our father left. Would the government take it away?

ZHEMISGUL: Our parents are both Kazakh citizens. Our father went to China on a three-month visa. It was about to expire, and they were refusing to let him leave—he felt he had no choice but to do as they said. They told him that even if he gave up the land, he would have to pay back all the rent money he’d gotten from the Chinese renter. This was impossible. We didn’t have any way of finding such an amount. The only other option, they said, was to give up his Kazakh citizenship, to become a Chinese citizen again. He had no choice. It was his name on the lease.

SUNGKAR: They lived at their relatives’ place until December that year. Our mother had a one-year visa, and when this was almost up she decided to return to Kazakhstan. But the authorities wouldn’t let her go unless she divorced my father.

ZHEMISGUL: They told her that if she didn’t want harm to come to her husband, she should sign the papers and then she could go to Kazakhstan. There was no ceremony. They just took them into a room where they signed the divorce papers. She came back in December.

SUNGKAR: Last we heard, our father is working as a security guard at Dórbiljin Administrative Sector School #1. He lives there as well. That’s right: at the school. Relatives are afraid to have him in their house, so he has nowhere else to go. We heard this from our mother’s older sister. She sees him in the street sometimes, and updates us on WeChat. But she’s afraid. She told us he was eating together with the students in the school and sleeping in the classrooms at night.

ZHEMISGUL: Our father is afraid to talk to us. It seems like he’ll be punished if he does. We hear about him only from our distant relatives. And our mother is living alone. Normally she’s the one who talks about our situation, who does this kind of thing. We’re not used to it. But the stress has given her heart problems. She’s had to spend some time at the hospital. That’s where I’m going now, to see her.

—Zhemisgul Yerbolat, 26, and Sungkar Yerbolat, 20 (Yerbolat Zharylkassyn, father)

Interviewed May 2019

ORDINARY PEOPLE WEREN’T BEING DETAINED YET

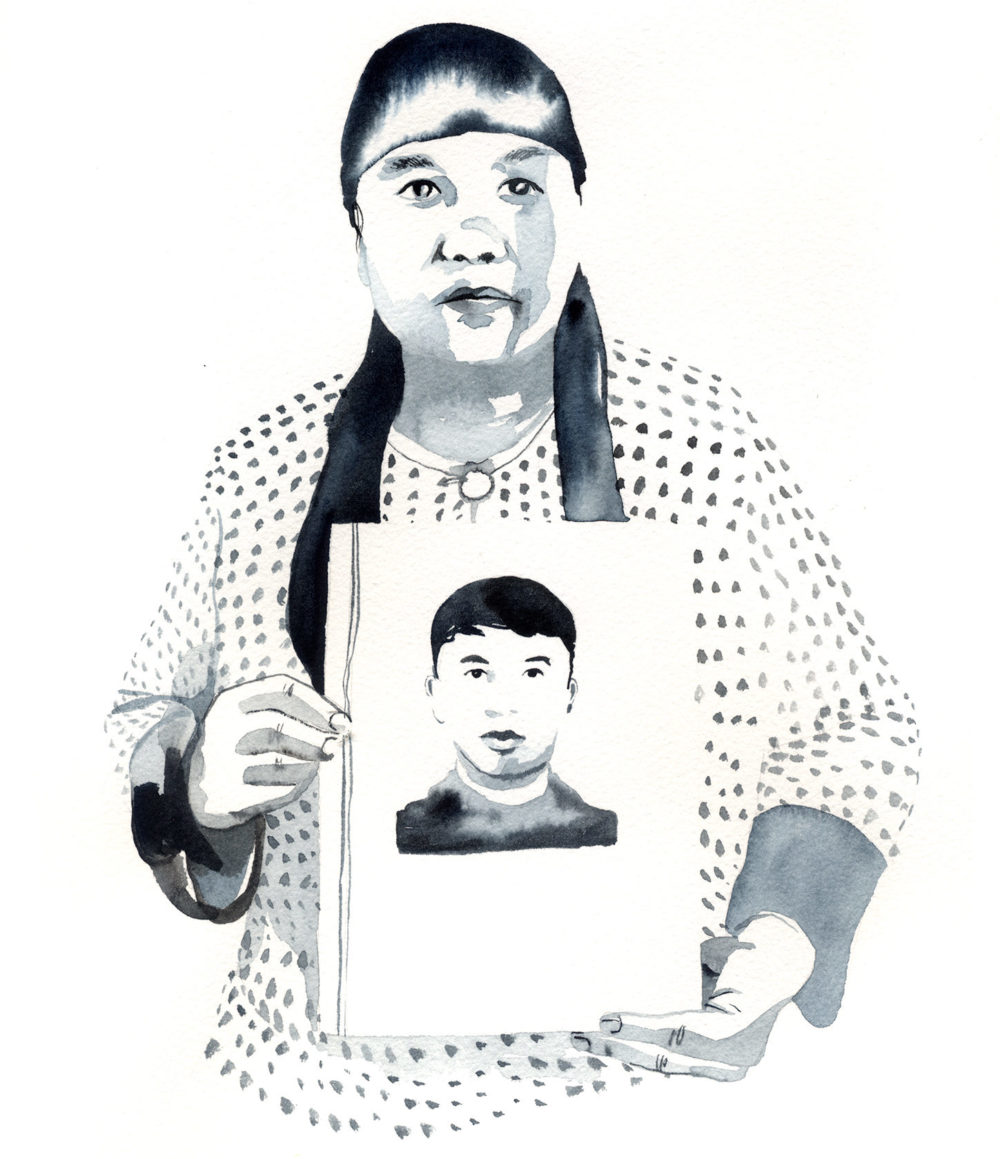

The photograph: a young man, head shaved, leaning on the bars of a hospital bed. He is wearing an Adidas jersey and has an intravenous cannula in his left arm, held in place by medical tape. Two women, one young and one old, are helping him stand. His gaze is urgent.

I’ve been complaining since last January. A year and a half. But I’m sharing this picture of my son in the hospital for the first time. I’ve been afraid they would find out who sent it. There are many, many Kazakhs who haven’t complained yet, who haven’t told their story. They’re afraid. I had to make a decision for myself. What do I have left to be afraid of?

The living conditions in Kure village, when I was still living there, were free at the time, but there were rumors. We heard they were detaining mullahs. Our village had two mullahs, and one day both disappeared. Word got around. Then we heard that Uighurs were being detained. Then they started sending police officers to our ceremonies. At a wedding, there would be policemen at the door checking guests’ citizenship. I didn’t think much about it at the time. Ordinary people weren’t being detained; not yet.

I moved to Kazakhstan, and in 2016 my youngest son joined me. He bought land and built a house in a village called Batashtuu. His intention was to move here for good. After he built his home, he and his wife went to China. They owned a barbershop there and wanted to sell it. They left their son in my care. It was supposed to be only a short trip. When they got to China, their transit visas were taken away.

The day they crossed, he called me at the border. I’m being interrogated, he said. Please send my son’s photos. I need proof he’s in kindergarten. I sent the photos by phone, but I’m not sure he got them. Two hours later, the phone was switched off. Two days later, my daughter-in-law wrote to my eldest son, who lives in Kazakhstan. Your brother was taken to study, she told him.

That was it for six months. Until June 2018, we heard nothing from him or anyone else. The first news we heard came in June, and it was this photo from the hospital. His wife had been called there to visit him. He’d had an operation. I don’t know what the operation was, or even what organ was operated on. We don’t know anything and our daughter-in-law can’t tell us. I don’t even want to tell you who sent me this photo.

After twenty days in the hospital, he was taken back to the camp. More silence. Months passed. Then, in November, he was released. Now he’s out of the camp, but we have no direct communication with them. Since November, my son has called us only twice, both times from a police officer’s phone. It’s the only way I can communicate with you, he told me. Don’t worry about us. We are OK, he says. Everything is OK.

But it seems he can’t get back his passport. It’s been almost two years now. My grandson is five and I’m still taking care of him. I need help. I want my youngest son back in Kazakhstan. He was supposed to take care of us, his parents. That’s the custom. Now my husband and I are alone in this big house and working odd jobs. Our son built this house for all of us. It’s ready; it’s a lovely house. But now it’s empty.

—Madengul Manap, 52 (Uljan Jenisnur, son)

Interviewed April 2019

Serikzhan Bilash moved to Kazakhstan in 2000, became a citizen in 2011, and co-founded Atajurt in 2017, as rumors began to spread about a mass internment drive of Muslims in Xinjiang. Atajurt became a lightning rod for refugees and whistleblowers, many of whom were entering Kazakhstan from China. His group of volunteers worked to resettle new arrivals and find money and housing for families who had lost their means of support. They also collected the testimonies that, starting in 2018, became the basis for much of the international media attention surrounding the camps.

We meet for the first time in Zharkent at the extradition trial of Sayragul Sauytbey, who had been forced to work as a language instructor in a camp before escaping into Kazakhstan. “We’ve never had a trial like this, open to the public, to foreign journalists,” Serikzhan tells me on the courthouse steps. “This will show the world what is happening in Xinjiang. It will show the truth about the camps.”

We meet again in the offices of a pharmaceutical company on the fourth floor of Almaty’s House of Printing, a Soviet-era building that smells like fried bread. One of Atajurt’s volunteers has invited me there to interview family members of some of Xinjiang’s disappeared. That August, in 2018, the room is constantly full. Serikzhan and his team are recording several testimonies every day.

Kazakhstan’s government refuses to recognize Atajurt as an official organization, despite Serikzhan’s frequent attempts to register the group. In February 2019, a court fines him more than six hundred dollars for the crime of leading an unregistered organization, a penalty that turns out to be only a prelude. In March, he is abducted from his hotel room by the state authorities and bundled onto an airplane bound for Kazakhstan’s capital city, now called Nur-Sultan. The police say his crime was “inciting national discord.”

I fly back to Kazakhstan in April 2019. My plan is to continue my work with Atajurt. But when I land in Almaty, Serikzhan is still under house arrest hundreds of miles away. No trial date has been announced. In the meantime, authorities have raided Atajurt’s offices. The group has relocated to a building nearby, but when I show up, most of the volunteers are gone. The rooms are quiet.

I DON’T KNOW—PROBABLY HE ALREADY DIED

I’ll tell you a story that describes my father well. I met and fell in love with a girl from Kazakhstan. We planned to move there together and get married. I was living in China and we were both teaching at the music school in Ürümqi where we’d met. She was famous, actually, a famous traveling musician, at least in the world of traditional Kazakh music. I’d admired her long before we met. It was a dream to have such a girlfriend!

Before the wedding, when it came time to celebrate the qyz uzatu, the girl’s farewell, we were still living in China. My father is old—he’s seventy now—and in bad health, so in the end he couldn’t come to Kazakhstan for the wedding. But he attended the first wedding, as we call it, the girl’s farewell, and as a gift for my wife-to-be he brought two small books on China’s Main Law and Criminal Law. Now you should memorize the laws of China, he told her. You are married to a Chinese citizen. Both of you must know the laws of China and Kazakhstan. You see, he was so confident in the law, in the Chinese judicial system, but in the end he experienced the full and exact nature of that system—he got it exactly.

Before he retired, my father had worked for the Ministry of Culture. He was an educated man living in a place where the literacy rate was still low, and Chinese script in particular was not widely known. This was in Tacheng, which Kazakhs call Tarbagatai.6 In retirement, he spent his days helping people fill out papers in Chinese. Mostly, they were writing complaints. He wasn’t a lawyer but he knew the laws very well, so he helped people file complaints and petitions with local authorities. That’s just how he was.

With us, he was strict but loving. Education was everything to him. After I was born, he never spent a night outside the home. He was at my side while I studied; my brothers too. He sent the three of us to the Chinese-language school. You have to study, he would tell us. You have to learn calligraphy. He taught us both Kazakh and Chinese script. He devoted himself entirely to raising us. When I first showed an interest in music, he bought the family a piano. If he didn’t have the money, he borrowed it. We never heard a word about money in the house. We were always provided for. As I got older, my father bought me music-studio equipment—nothing big or fancy, but it was still an expense. We weren’t rich. Somehow he got the money.

I left home when I was nineteen and drifted, as musicians do: Ürümqi, Beijing, Shanghai. In 2014, I met my wife, and we came to Kazakhstan looking for jobs. My father had never traveled anywhere, but when I told him we were moving, he accepted it. You know your own mind, he told me. It’s your life. As I said, he didn’t attend my wedding, but when my child was born, in 2016, he came, even though he was already in bad health. He had no teeth, and his legs were fractured everywhere. He suffered from cirrhosis, heart disease, arthritis. He could barely walk. Even now, I don’t know his feelings. Did they want to move to Kazakhstan? Stay in China? Should I have suggested it? I know they were afraid. If they died in Kazakhstan, would their relatives be able to attend the funeral? I regret that I never asked my father if he wanted to move here, but people in our town weren’t used to speaking openly about Kazakhstan. It’s considered almost treasonous in China to discuss it—to talk about leaving. I only ever talked with my two brothers. I urged them to come here. As for my elder sister, she’s married to a party official. Her husband doesn’t want to move.

In March 2018, I had just become a Kazakh citizen. Every day, I’d send my mother a picture of our daughter on WeChat. That was how we kept in touch. Gradually, her messages became less frequent. Of course I’d heard that Xinjiang was getting difficult. I suspected this was the reason for her silences. That month, she removed me from her WeChat contact list altogether. I asked my brother why. I called him on video chat. He was visibly upset but couldn’t cry. It’s difficult here, he said. Not like before.

I was afraid local authorities might not treat my father well. He was a thorn in their side, helping neighbors write complaints. Before I hung up, I told my brother to let me know if anything happened.

The complaint that finally did him in was about a murder. A man named Zhumakeldi Akai was beaten to death by security guards at a reeducation camp. They took his body to his home to be buried. He had awful wounds. His wife came to my father. She wanted to make a complaint. They killed him, she said. She begged him to help. So my father wrote a letter to Beijing, but the letter never left the prefecture. The local authorities confiscated it. They paid my father a visit. So, they said, you want to blame us for this death before our superiors?

This information came to me through different channels. I’ll tell you exactly how, but I don’t want you to write it down. I don’t want the authorities to close these channels, and I don’t want the people helping me to get in trouble. In short, my family members were all detained right after my father wrote this complaint about the murdered neighbor. Someone—I don’t want to say who—told me soon after it happened.

But even before I was told, the night before their arrest, I had a bad dream. My heart was aching. I saw security guards following me, trying to catch me, and in the dream I had a thought: What is going on at my house? When I woke up, I knew something had happened.

As soon as I got the news, I called my sister in Ürümqi. Even with her husband’s status, she didn’t know anything. But she called our aunt and confirmed they were detained. I began to gather information from different sources. I called everyone I knew. In some cases, I don’t want to say their names. They’re still back there. These days, everyone knows about the weather code, so no one uses it. If I said that it was getting warmer, those listening would know what I was talking about. I have a different code. I don’t want to say what it is. But I have a code I use.

Eventually I got the whole picture from different people, some of whom had been detained with them, others who lived nearby or who heard secondhand. First, they detained my father and my two brothers. They did it without any warrant. They just disappeared. My mother went to complain to the local district authorities. She asked them for an explanation. The officials were happy she’d come. Ah, good, you’ve brought yourself in, they said, and detained her too.

After several months, my mother and brothers were released from the camps, but my father was taken somewhere else. He vanished. In the absence of any news, my wife compiled four invitation letters—the letters you write to bring family members into Kazakhstan—and sent them to the local council in my father’s village, if only to get some information about his fate. This January, we finally got a response: a letter stating that in October 2018 my father had been convicted to twenty years in prison.

Now I don’t know if he’s alive or dead. We didn’t get any information about the trial or any crimes he had committed. Not even my mother was aware of his sentence. All I know is that he’s no longer in the local prison where he was being held. I expect he was transferred to a place for people with long prison sentences. But he can’t eat, as I’ve said. Even in the local prison, they served him only stale bread and hot water. People who shared a cell with him there told me they would wet the bread in the water and feed it to him. He was handcuffed; he has no teeth. Without their help, he would have starved to death. [Despairingly] I don’t know—probably he already died.

I’ll tell you something else. My father was tortured. I can’t tell you where I got this information. It came from a prisoner who was released, and who managed to escape to Kazakhstan. There are many people like this. Most of them are simply in hiding. They don’t reveal what’s happening, because they’re afraid. This particular informant lives in Kazakhstan but won’t do an interview himself because his daughters are still in Xinjiang. I communicate mostly with people like this, often people I know personally from back in China. I know I can trust them. I don’t want to spread rumors or exaggerations. First, we should find the facts, what the reality is.

Now my brothers and mother are home, but a camera is installed in their house, watching what they are doing. I know they suffered in the camps. I am ready to die for them, and for my father too. I’m not sleeping. I cry. Men aren’t supposed to cry, but I cry. Twenty years? It’s a death sentence. And why? If there was an error in the last complaint he helped write—show me the error! My father was arguing that this man’s death was against Chinese law, which was not written by me or my father or any Kazakh. It was written by the government. It should not be subverted. Law is not like physics or mathematics—it’s not confusing. What it says is clear. We can understand it. It should be followed. My father did not break the law. He was following the law. It’s the authorities who are violating it. And now my family is back in China, but my father is nowhere.

—Akikat Kaliolla, 34 (Kaliolla Tursyn, father)

Interviewed April 2019

Kairat Samarkan once dreamed of becoming president of Mongolia. “I don’t know why,” he says. “Since China was such an enormous country, and Mongolia was small, I suppose I thought I had a better chance there.”

He grew up in a family of herders in Xinjiang, near the Mongolian border, in a village where everybody kept cows and sheep. His parents both died suddenly, a few months apart, when he was still a child. After that, he says, he was grotesquely poor, an orphan with no one to take care of him. We meet in August 2018. As we sit drinking apple juice in the dim private room of an empty café, he goes on to describe a more recent ordeal: his arrest in Xinjiang, in 2017, and his subsequent detention in a camp in Karamay village.

“I was disobedient at first,” he says. “I wasn’t used to such strict orders. They put me in restraints, a chair with cuffs for my hands and legs. They bound my chest, and made it so I couldn’t move my head. There was a separate room for the disobedient. Usually they would put people in the room for three hours. After three hours, it would hurt like hell.”

At other times, he was forced to stand in stress positions for hours. “They didn’t beat people,” he says. “They made them stand like this or like this”—he stands up to demonstrate the positions—“or they forced you to sit down and stand up over and over again.” The threat of torture made it impossible to do anything other than submit to authorities. “It didn’t take me long to start obeying them.”

AT LAST MY BACK CAN MEET THE MATTRESS

My uncle Raman Zharkyn was born in Zhiek, a small hamlet in Kurty township. His name should be Rakhman. But it was a religious name—forbidden—so my family entered Raman in the ledger. He was a prominent man in our village, and in May 2017, he became the head of Zhiek. On November 20 of the same year, he was taken to a reeducation camp. He was abducted directly from his office.

The reason given for my uncle’s detention was this: Every Friday he’d been going to the mosque in Kurty, the administrative center nearby. At some point, he and a few friends decided to raise money for the building of a new mosque in Zhiek. He and his friends were all arrested.

For seven months after he was detained, he was in a prison under interrogation. He spent those months in a small, damp room, cuffed to a chair, his hands and feet restrained. He wasn’t allowed to lie down. He sat day and night. During his first month in the prison, he was also restrained by a cuff around his neck, connected by a chain to the table. This cuff created an open wound that wouldn’t heal. He developed a fever. At last, they took him to a hospital. They called his brother, another uncle of mine, to the hospital, and that’s how we heard all that had happened to him.

His brother said that when he first came to the hospital, there was a black cowl over Raman’s head. When they removed it, his brother didn’t even recognize him. His hair was matted and uncut. He’d lost weight. The wound around his neck was severe but he was still wearing the cuff. The officials refused to remove it until the doctors insisted that the wound wouldn’t heal otherwise. Only then did they take it off, after securing permission from some higher authority.

After this ordeal, he was sent to a political study camp, where he spent another eight months. But he got sick again and was returned to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. His mother managed to see him after he was transferred to the camp. It was the first time she had been able to see him. He told her that, compared with prison, the camp was like a home. At last my back can meet the mattress, he told her. His mother has since lost her eyesight. It’s the stress. She’s had two operations on her eyes, and one is now completely blind.

Raman’s wife, my aunt, had been a housewife. When her husband was taken to prison, she went to work as a dishwasher at a restaurant. But she had to quit to take care of her mother-in-law when she went blind. Now they’re surviving on charity.

In March, my uncle was sentenced to three and a half years in prison. My father is worried about the fate of his brother. But his own heart is bad, so we don’t tell him all the news. Only his wife is allowed to meet with him, and then only to bring him his tuberculosis medicine. [Through tears] I don’t think he will be alive by his release date. The conditions there are harsh. The food is bad. That’s the question that bothers us all: Will he be alive by the time he’s released from prison?

—Zhainagul Nurlan, 33 (Raman Zharkyn, uncle)

Interviewed May 2019

IN THE HOMES OF THE DISAPPEARED

As Gulshan speaks, she grips a crumpled pack of tissues.

Mostly men are taken to the camps. What happens then? The authorities send loyal Chinese families from the coast to live with the women in the homes of the disappeared. A Han Chinese man is sent to Xinjiang and placed in the house where the detained person had lived. Or it could be a couple. Or a family with kids. But sometimes it’s just one man who is sent to live in a house full of women…