This is the first entry in a new, recurring feature in which Believer Eco-Thoughts correspondent Leslie Carol Roberts talks to today’s most robust and generous thinkers around ecologies and the sixth extinction, to ponder and examine how we collectively message and metabolize our fate. What do we all feel now? The thinkers featured here will be drawn from an international group of emergent and established writers on the topic, humans already offering ideas on our collective path, as humans and nonhumans.

“I heard someone from NBC saying, ‘We just don’t know how to make climate change compelling.’ I immediately tweeted and was like, ‘I’ve got a line to use. Something is coming. It’s really huge. And it’s going to change your life.’”

Hyperobjects include:

Oil spills

All of the plastic ever made

Embarrassing lapses in human judgment that, given time, will decay

On a languid Friday, Timothy Morton, Rita Shea Guffey Chair at Rice University, and I sit outside a pub in Houston, talking about the word weird. Across the quiet street, a sign advertises Adam and Eve, a chain sex toy shop, in glowy purple. I watch people drift in and out of that place as Tim defines what he means by “weird,” oft-pondered in his twenty-two books and the hundreds of articles in which he lays out his ecological thought.

Tim, take it away:

Weird from the Old Norse, urth, meaning twisted, in a loop; the less well-known noun weird means destiny or magical power. Weird: a turn or twist or loop, a turn of events. Yet weird can also mean strange of appearance. In the term weird there flickers a dark pathway between causality and the aesthetic dimension, between doing and appearing, a pathway that dominant Western philosophy has blocked and suppressed. Now the thing about seeming is that seeming is never quite as it seems. Appearance is always strange.

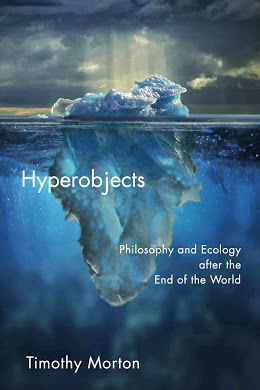

Morton, considered one of the 21st century’s most dynamic and creative philosophical thinkers, has a genius that shapes and entwines arguments from high and low cultural references. He’s a philosophical tinkerer who rarely recoils from the facts and horrors of today’s ecological calamities. In fact, he finds a sad sweetness in our shared fate. And that seems to make people in the Western world feel a bit better about the slow realization that everything is going to die—given our predilection for beef and fossil fuels and fascist governments. Part of a movement called Object Oriented Ontology, Morton coined the shimmery concept hyperobject to describe vast, unseeable, and yet limited things like climate and plutonium. He regularly collaborates with internationally acclaimed artists on expansive, interdisciplinary explorations where he serves as thought partner for the artists’ conceptual imaginings.

When the pub closes at 2am, we wander back to his cottage. Soon it’s 4:30am, and Tim is describing the late-80s acid-house music scene in London, a scene he views as gestating a core part of his eco-thinking. We have covered street wisdom, Yoko Ono, French eco-feminism, Wordsworth’s poem Lines Composed Above Tintern Abbey to name a few. I collapse on his couch as he tells hilarious Lacan jokes and details the Norwegian predilection to over-explain, which he dubs “Nordsplaining.” And then I drift off. We roll out of the cottage some time after the sun comes up, our eco-conversation unfurling before surrealist art at the Menil Collection to cover everything from his work with Laurie Anderson, the recent show in Marfa on the Hyperobject; and Being Ecological, perhaps his most accessible book. It is a viscous weekend, a sea of ideas and tender comments on humans and non-humans, eating sushi in a strip mall, sipping Mezcal, playing with his cat, watching Blade Runner, laced through with meandering digressions around building better ecological imaginaries as writers and artists. This is thirty-six hours with Timothy Morton.

—Leslie Carol Roberts

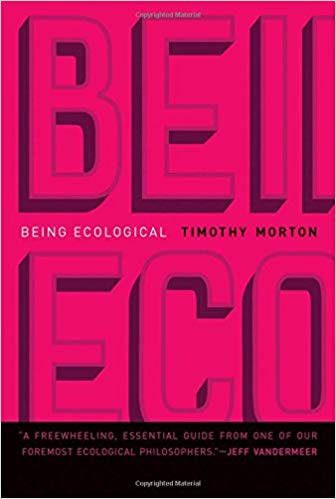

THE BELIEVER: In your most recent book, Being Ecological, the ideas you articulate about the fact that we currently face down the Sixth Mass Extinction are beautifully complex, and tender. Usually our collapsing ecologies are narrated by speculative imaginaries that include chaotic, mean humans—you know, people hunting and eating other people.

TIMOTHY MORTON: Basically, it’s a book for people who don’t think they care about ecology. Everyone who wants to believe in it, who wants to do something about this is already there—and we need billions of people doing things about it and thinking about it. We need people who think they don’t care.

The way we have right now is basically twofold. If you look at the newspaper, page one is going to be some kind of information dump—there’s going to be some factoid, from scientific research, and it’s going to be a number, like two-hundred-thousand blah blah blah. Five, ten years, and six percent. The next day in the middle of the paper you get the editorial which is someone telling you that you’re very bad.

I decided to write the book that doesn’t make us all seem stupid and evil—the book that shows you how actually being ecological is just like being a teacher or a parent. At first you try to be a parent and it’s daunting, and then you get to relax. Because you realize that you are a parent. There’s someone in the room who knows you’re the parent. They just know, so you can let go. It’s very important: you don’t have to be ecological because you are ecological. It’s supposed to be very reassuring.

No one else has said we need billions of people right now caring about this, and yet, the only person I can blame for the situation with any ethical or moral authority is myself. What am I doing wrong? I wrote this book to think about what it was that people like me are doing wrong.

BLVR: You talk about trying to get people, in a nonverbal way, through performance and objects, to understand these large, physical, finite “hyperobjects.”

TM: Me and Laurie Anderson recently did a performance called “It’s Not the End of the World. That Was a While Ago,” at Rice University. It was very much about how you’ve got everything you need right now. Laurie Anderson’s a very uncanny, spooky artist, and a genius composer. Someone asked, “What do we do that’s important enough to be put to the test?” And then she held her body still, absolutely still. It was quite, quite beautiful—she just embodied being and everyone was like, “Oh wow.”

A couple of years before that, when we first met, Laurie did something, acting as a responsible kind of artist elder. At the Day Into Night festival in Houston, she took this crowd of twenty-somethings through Yoko Ono’s Scream Piece—she had them scream at the top of their lungs for twenty seconds. The appropriate reaction to the climate emergency actually is this. It’s not just curling into the fetal position—it’s a horrifying scream of terror and pain … so how to get people to the scream without forcing them, because no one wants to scream like that. Laurie just did it. And she was laughing while she was doing it and it was like, Wow! Laurie, you’re helping people because twenty-something people don’t want to scream. I thought this was awesome and responsible and amazing.

BLVR: You said you first connected with ideas of ecologies when you were four years old, in London?

TM: Yes! So when I was four years old my mum gave me a UNESCO book called SOS: Save the Earth. It’s from 1972. And it has cut-out postcards in the back that you can send to your MP and it’s perfect. It’s absolutely clear and comprehensible. Everything we know now, was known in 1972, which is deeply shocking. Nowadays, for example, I heard someone from NBC saying, “We just don’t know how to make climate change compelling.” I immediately tweeted and was like, “I’ve got a line to use. Something is coming. It’s really huge. And it’s going to change your life.” We knew this in 72!

BLVR: You mentioned the book Hyperobjects spilled out of you in fifteen days. And that it made itself through your voice, through performing the ideas as talks—a multi-year series of talks around the world—and by looking at how artists were expressing ideas of form? You mentioned that MacArthur Genius Award-winner Tara Donovan’s work was a spark for the concept of the “hyperobject.”

BLVR: You mentioned the book Hyperobjects spilled out of you in fifteen days. And that it made itself through your voice, through performing the ideas as talks—a multi-year series of talks around the world—and by looking at how artists were expressing ideas of form? You mentioned that MacArthur Genius Award-winner Tara Donovan’s work was a spark for the concept of the “hyperobject.”

TM: Tara Donovan’s roomful of plastic cups—it’s an entire room of cups stuck together and it looks like a sort of billowing cloud. And think of all the plastic or Styrofoam cups in the world forever—that was the first type of “hyperobject” I ever thought up. How do we talk about that? What is that? Now we’re all aware of all the plastic and beginning to realize there is a hyperobject plastic thing. It’s not just like cups and saucers and stuff; it’s like little, tiny micro bits that get inside of everything. Its vortices in the ocean. And it’ll be going on for thousands of years.

BLVR: And then you included Donovan’s work [Untitled, Plastic Cups], which appeared as a photo in Hyperobjects, as part of the Hyperobjects show at the Marfa Ballroom in 2018.

TM: The Marfa exhibition was like trying to get people into that feeling of like, Wow, there are these gigantic things. And there’s a word for them. Hyperobjects aren’t god-like terrifying beings that are inevitably going to kill you. They are actually finite. They’re more like Titans, I think, than gods. And it’s well known that you can defeat Titans. Just think about the actual ship, the Titanic: It got defeated by an iceberg. You can do something with and about these hyperobjects because they’re physical. Plastic doesn’t go on and on and on, forever. It doesn’t go on for five billion years. It goes on for a very long time. It’s embarrassing. It’s easier to imagine uncountable infinity than it is to imagine a hundred thousand of anything. And so people now have a word for something really scary and big—hyperobject—and it’s empowering, you know, people tell me, to have this word.

BLVR: What else influenced you toward thinking about ecologies in this specific way? This way of art and objects, away from the theory and your academic training at Oxford.

TM: I used to listen to recordings such as Sounds of the Humpback Whale. I was really into that as a kid. And then the Natural History Museum opened the ecology exhibit, which, before it was co-opted by BP in the 80s I think, was actually very socialist. It was a very beautiful, very mind-expanding, incredibly simple exhibit. That had a very, very strong effect on me.

Before I got to college, I read a lot of French feminism and it just so turns out that it is obviously very ecological; Françoise d’Eaubonne created the term, eco-feminism, in the 1970s. Isn’t that amazing that at the same time on the planet there arose a way of talking about ecology that was feminist in both the USA and France? And I got saturated in this stuff in my first year of Oxford. I actually got taught a lot of French feminism by very generous graduate students in the lunch breaks. The official religion we were all in was Terry Eagleton’s brand of Marxism.

BLVR: And your “interstellar” relationship to music?

TM: Music teleports me to the outer moons of Saturn immediately when I hear an amazing chord. And I start playing, and I might end up playing five, six hours without noticing anything else in the world. And to be honest, I’m not good at it. I love playing, and I’ve been in bands, but I’m not like my brother who is a genius drummer, Steve. He was going to be in Jamiroquai before he got schizophrenia. I’m not a virtuoso violinist. It’s not the greatest idea of a career for me.

BLVR: So music creates a very different experience design than “lecture.”

TM: There’s something important about music because it allows people to resonate with what’s being said. And to resonate with someone else, for no reason. Something happens in my lectures when the feeling and the sound, the rhythm, and the sentences, all start to work on the audience. We often land in a place, in the Q and A, that’s very contemplative, and there’s a feeling of connection. Which maybe you could call solidarity. But the feeling isn’t a choice, it’s not something you have chosen to do, politically. It’s just a state in which you find yourselves. And this is very important to me: helping people to know that there is stuff already there and all you really have to do is sort of let go and notice. Maybe the way I get involved with artists has to do with helping people do that, to feel in a more physical—and less conceptual—way, basically.

BLVR: “Weird” is a go-to word for you. Is there something “slightly weird” about our human quest to understand being ecological?

TM: You just have to think about the fact of being born, right? You popped out of someone’s vagina. You came from some other body. And of course you came from loads of other things and there’s all that bacterial microbiome and stuff, without which you wouldn’t exist. It’s all very strange and slightly weird.

But the point is this sort of Levi-Strauss thing—where myth is supposed to be all about how we interpret ourselves and where we emerged from or, did we come from something else?—isn’t true. I think anybody on the planet would know they popped out of a vagina or a test tube or whatever. I don’t know quite what the word for that is but patriarchy doth spring to mind—as an indicator of why it would be amazing to you that you were born out of a woman’s body. And by the way, this isn’t strictly or essentially about women’s bodies per se: you can be born out of a test tube. When you’re a scientist, you have to accommodate yourself to all these sorts of data.

BLVR: We have talked extensively about the scientist’s view of the world. That feeling of being a scientist.

TM: For me, the feeling of being a scientist is that allowing of strange new things into your field of vision, as it were. And being passionate about learning about these things, and connecting to these things. And so my idea is to empower people to feel like scientists without having to have a degree and all those sorts of credentialing. Just very, very ordinary and showing people you have got the controls. We can do this. We know what this is. We’ve had this before. I think just this morning, Leslie, we were talking about these city projects in the suburbs of London. In part designed by people like William Morris. We know what this is. We’ve got this. We do! And all this talk about how we’ve got to think and do something special. And all this talk about all these facts! Clobbering ourselves all the time with facts is like being a deer in the headlights, not doing anything but simply feeling paralyzed actually and sort of disempowered—a slob or stupid and evil. I want people to feel intelligent and good because that’s what’s going to help the polar bears. You know it’s no use just rolling around in the fetal position going oh my god that’s extinction because then you are actually part of the problem. And even if we can’t fix it, we might as well be intelligent and loving and caring about the life forms that are here right now. And this brings us onto the topic of “here.”

BLVR: Yes! Here! and Yoko Ono’s work This Is Not Here, which is at the center of Being Ecological.

TM: Part of the book is a kind of transmission of the ecological rather than an attempt to persuade you. The way I did it was to ask Yoko Ono to put some of her art in. The art that I got was her piece, This Is Not Here, one of the first artworks that really slightly pushed me or scared me. Of course, here is like, we’re in Houston but we’re also in Texas but also on Earth but also in the solar system. Now it’s 3:20 pm, and it’s also the time of the Anthropocene, and it’s also the time of humans on Earth, and it’s also the 21st century. Ecological awareness can start by being aware that we inhabit multiple time-space scales all at the same time. This problem will be a 100,000-year problem and it will also be a 20,000-year problem and a 5,000-year problem and so on. There’s all these different ways of thinking about the effects of global warming, for example, and all those timescales have different things happening in them. You’re a different kind of person on different scales. On one scale, you are starting your car and not much is happening to Earth. On another scale what you’re doing is actually destroying it.

BLVR: Overlapping. Here and now.

TM: To really be aware that you’re a human is an uncanny awareness, because there are parts of you that aren’t in your direct control. You’re a member of all kinds of overlapping groups. You have all these bacteria, you’re not just a human on your own. You have all these other life forms that you depend on you and so on and so on. I read this book Zen book, called Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind when I was a kid. It was written by Shunryu Suzuki, who was this fighter pilot in the Second World War. He decided to change his life and started the San Francisco Zen Center. The Zen Center is where I think he wrote the book; and in it, right in the middle, is a blank page and a picture of a fly. You are reading, reading, reading, and then pop! this visual, nonverbal thing happens and it’s sort of like a mind transmission, actually. I really wanted something like that in my book Being Ecological. And amazingly Penguin, what they did, was sandwich the phrase “This Is Not Here,” between the word “metaphysics,” and then two pages later, “of presence.” They found exactly the right place. It has to do with the idea that nothing is stable and solidly here. Everything is sort of meltingly temporal all the time, like the soap in the bath and that’s the idea of “here.” I like to call it “nowness” rather than “here and now,” because really it’s a feeling, not a thing you can point to. That measurement stuff is just things on maps and clocks that were enabled by whatever phase of technoscience, or neo-liberal imperial whatever that we’re in right now. That’s someone else’s time. That’s just the measurement of time. Again the tactic is to put people back in their body.

BLVR: The words Here/Hear.

TM: There’s a certain kind of urgency to the word here. It’s not just a dart or a finger pointing at something. We talked about how you wrote your recent book, Here Is Where I Walk because you wanted to perform how ordinary walks by an ordinary person are deeply ecological. You said daily walks are for you an act of solidarity with non-humans and a protest against the tech bros. Presence and gentle observations.

BLVR: We both were talking about that, the rise of the hard-sided mindset of Silicon Valley, which is proximate to where I live and their endless push to solutionize climate change and human and non-human behaviors and relational identities? We also talked about activism. Do you need to wave a flag to be an activist? Or are there gentler, quieter ways to be ecological?

TM: Yes! On that note: is acting, or doing a “let there be light,” sort of God trick—is that what we have to do when we’re being ecological? Or is it actually more like being in a band, and listening to everything, like listening to the other musicians, listening to yourself, listening to the instrument? Paying attention to the butterflies, being aware that there’s the ocean, knowing that you have a bacterial microbiome—all that stuff is like being in a band, actually. Act can mean join in with and appreciate. And so it’s a kind of listening.

BLVR: I love that idea. Awareness and listening! Being quiet and paying attention! We live in this loud, chaotic miasma of ecological data. It can be debilitating to listen to the BBC or read The New York Times. You write quite powerfully about facts and data. And I think people feel empowered by it.

TM: Ahhhh, Leslie! We all already have sensations and feelings; we’ve got everything we need to do to be more ecologically aware and more just to more lifeforms. That’s a much nicer way of looking at it than where we’re at right now, rather than some sort of sort of endless atonement for our sins. It’s this kind of finger wagging, this quality of ecological writing, rather than to do with pleasure.

BLVR: Let’s go back to music, how there is musicality in everything you do?

TM: I hadn’t really done music with people, I think, until I wrote this opera Time Time Time. It was a beautiful collaboration with Jennifer Walshe. We talked and laughed for two years and then she said, “Go!” I wrote some pages and she made the libretto. An opera is big-time “doing music” with people. But there’s musicality in everything I do. As I said, I am very sensitive to music. Both my parents are musicians. Both my brothers are or were musicians. They’re very serious musicians, and make money out of it; it is their job. There’s a way in which I can’t help feeling the music of things and my life is made a little better by being a little bit oblique to it. Because music is a more powerful source to me than words. Words are easier to handle.

BLVR: And the “musical” discussion you had over email with Björk, which became a book that was part of her show at the Museum of Modern Art?

TM: One day, I got an e-mail from Björk and she said, that she’d love to do something with me. And I thought, gosh, I would like that. How fantastic. And so we just did it. I immediately just tried to talk to her like an equal. We really did play with each other in that way that I was saying, about playing music together, only in this case it was sentences. They were very musical and lyrical. If you try to understand it, it might not work. But the feeling of it is very poignant and beautiful and it’s the same with this opera I wrote. I think it’s also the same with the hyperobjects exhibition I did in Marfa.

BLVR: About the Hyperobject show at Ballroom Marfa in 2018: You said, “the point of that was actually not to inform people.”

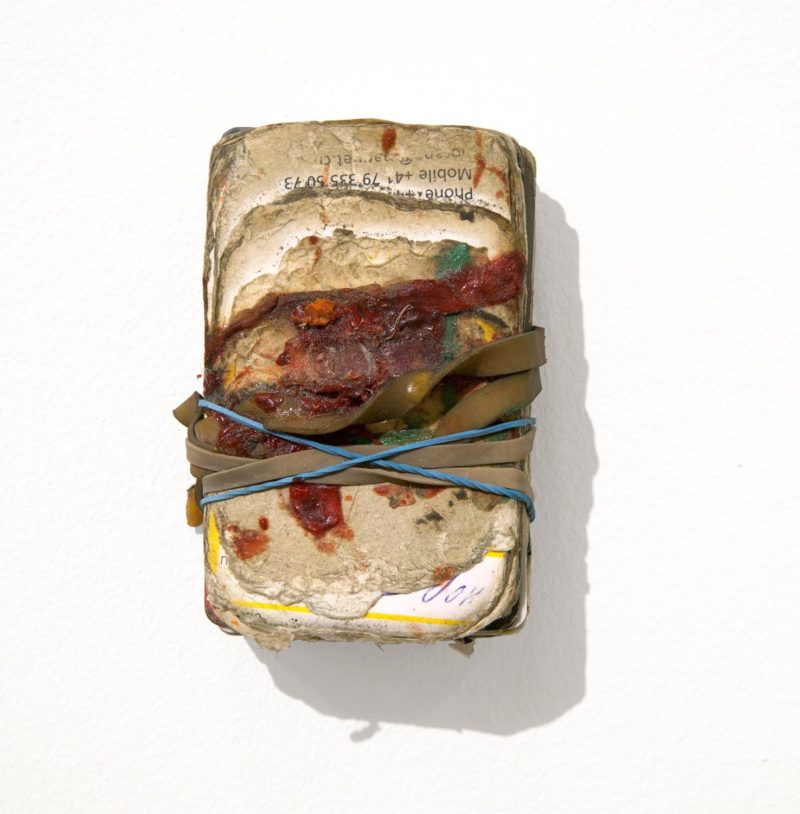

TM: Well, not in a purely conceptual way in any case. We didn’t have any labels and we didn’t make any distinction between the art and the pieces there for context, like rocks from billions of years ago, from the neighborhood. Instead we just put these things in a museum without any comment. You didn’t know whether this line of rocks was actually a piece or not and you didn’t know whether the line of rocks that actually culminated on the wall in my friend Paul Johnson’s piece Wallet was part of it or not.

The point being that there’s a rock from billions of years ago, there’s a rock from millions of years ago. There’s a rock from thousands of years ago. There’s a rock from hundreds of years ago. There’s a rock that was probably formed within the decade. And then there’s Paul’s piece, The Wallet, which was five years old, sculpted by his trousers.

BLVR: The Wallet?

TM: One day my mate Paul dipped into an old pair of pants and found this cheeseburger-looking object, which used to be a wallet. His pants and him sweating, basically, had made this object without him doing it deliberately. It’s a beautiful example of an unconscious thing, very untechnically, things you’re not aware of shaping you and shaping the world around you, and being part of your lives. That’s also what we’re talking about with ecological awareness. This little wallet is a symptom of all kinds of things, like walking across streets, throwing things in washing machines. There’s a whole bunch of stuff that’s hard to point to all at once. What is the name for a whole bunch of stuff that you can’t point to all at once? Well, my name for it is hyperobject. And so although the wallet is very small you could see it that way, like a raindrop is a signal of a hurricane. The wallet is a signal of human activity that that is unconscious, you know, just like an oil spill is a symbol of human activity that needs to become much more conscious, if we’re not all going to die.

BLVR: Your touchstone in the academy is also as a scholar of the Romantics. William Wordsworth, Percy Shelley?

TM: At this Wordsworth conference, the first one I went to, there was a keynote speech by Jonathan Bate, who sort of owned this nascent area of ecological criticism that was at that point called ecocriticism; and it seemed to me that it was quite conservative and reactionary. I freaked out! I thought, how am I going to write my PhD given that this is the dominant thing and the people who will read my book manuscript will be people like him? I actually spent twelve years thinking out how to pitch what I was saying in a way that this kind of person wouldn’t delete. In the end Jonathan, whom I like a lot in fact, was indeed one of the readers of my book, Ecology Without Nature, for Harvard—I’ve enjoyed working with him and I’ve written essays for him.

Before then I knew that I really wanted to write about something intuitively ecological, but without trying to talk directly about it. And so I thought I would write about food. I wrote a dissertation on Percy Shelley and vegetarianism. It was very hard at the time, because everybody thought if you’re writing about vegetarianism, what you’re trying to do is proselytize rather than analyze. People found it very hard to understand why I needed a job, because they thought I was an apologist for something, not just a researcher of it. And why can’t you be both? At the time I was extremely vegetarian. But I wasn’t trying to make people be that. I was just interested in the dynamics.

I remember quoting Adorno to you, who said the best image of Utopia is the idea of peace. His image of peace is floating on the water. An animal floating on the water, looking up at the sky—and I’m getting goose bumps just talking about it! Along with giving people the science, finding what is utopian in art and then making it very clear to people in an emotional way is my career. That’s what I do for my job. When I’m writing about art or poetry or whatever, I’m finding the utopian bit, the bit that could be better, in other words the future.

BLVR: You also have talked to me about what you learned as a kid in class-strapped London; ideas that really left a mark.

TM: I think it is important to mention that a lot of my ecological feelings and thoughts came from, number one, band practice in London with people who dropped out of high school. I never got good advice from my colleagues and teachers at Oxford, not really. What I got was from my friends, who were basically involved in that kind of street mysticism—I think everyone knows what I am talking about, just go visit your local headshop. My main point is that a lot of ecological thoughts I have come from embodied music, and dancing. I’m from 1988, Leslie, and you know I am from the acid house generation and 1992 was about going to three or four massive raves. One of the best was in Wales, on my birthday, and then going to Glastonbury. In ways, good philosophy is street philosophy, like street food.

If you want to experience “this is not here,” you could do worse than the Orb’s A Huge Ever Growing Pulsating Brain That Rules from the Centre of the Ultraworld. I mean, where are you in this tune? One of the aspects of it is this: it sounds like this magnificent sunset. It’s like, oh my God! It’s sort of about the sexuality and the feeling of being ecological rather than trying to go somewhere different—if you see what I mean?

BLVR: I do! And I think some people reading you now, for the first time, are surprised to learn that your early scholarship and PhD looks at vegetarianism in 19th-century Romantic poetry. But yet it’s here in your ecological writing. You frequently reference Wordsworth’s Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey?

TM: I recall being at Oxford and also playing in the band and I was a few miles above Tintern Abbey, a ruined Catholic abbey – the site of Wordsworth’s poem Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey —high above it in a number of different respects, because psychedelic drugs were part of this. I felt Wordsworth talking about nature being cool and I thought, what happens when you turn up the volume on that? You lose this “nature versus non-human distinction” that he’s implying. He’s really trying to make you feel science-y too. He’s all about like, when you hold a magnifying glass to something, it starts to look really weird. If you climb up a rock, it’s no longer picturesque. It’s this weird, gnarly, peculiar thing.

BLVR: Your work today is for a much-broader audience, for the global human community?

TM: Well. part of me wanted to write an introduction to my first really full-on eco-book called “Lines Written a Few Miles above Lines Written A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey.” I’d been to a fantastic rave in just that exact spot on my birthday in 1992. I never wrote it, of course. Because I wanted to sound sort of academic and scholarly and a little bit dry. Writing for lots of people isn’t about a “broader audience,” that’s a bit condescending of us scholars to put it that way—it’s up a level from being right; it’s about engaging the reader, because writing is really about reading and listening. Earlier in my career I was wanting to talk to credentialed people in the academy mostly, who didn’t necessarily understand this earthy stuff. If you go on about raves and beats, then you’re going to lose a lot of those people. Part of working with artists has also been like getting the beats back in.

BLVR: Yet academic life has offered you tremendous freedom?

TM: I grew up in a very precarious situation. Being at Rice is akin to being in a monastery, then being able to float around like a balloon tied to a railing, because Rice is very tolerant and generous to me. It is really good for me because it provides a stable anchor. I don’t feel like I’m going to lose everything. This is like the first time in my life I’ve actually had a thing called money and so I’m one of these people like Paul McCartney.

BLVR: Ah, yes the John/Paul thing.

TM: Well, maybe more the Beatles versus the Rolling Stones. The working class boys versus the art school kids. Paul, really not averse to making lovely products and making a bit of money because he was a working class guy from Liverpool. Wasn’t it great that he did that? Because he was able to invite into the band a guy called John Lennon and John Lennon was able to become pals with Yoko Ono and Yoko Ono did This Is Not Here and that’s in my book, right? And they got Bobby Seale on the Mike Douglas Show in full Black Panther regalia. My relationship to capitalism is quite much more straightforward.

BLVR: On Twitter you offer pretty strident opinions about the politics and economics of these times. I would not have guessed you had this warmth for capitalism.

TM: You can be left-wing and communist and socialist or anything you want without this twist, without this sort of art school, “a new kind of Rolling Stones” sort of old-school kind of twist to it—where you’re kind of above certain things you find distasteful.

BLVR: I wanted to end with some thoughts on the artistic collaborations of the last five years or so. You were just in London at the opening of Olafur Eliasson show, the Danish artist whose work you write about and who is a close pal of yours?

TM: You know it has been so so so so positive to have these collaborations. It has been like Wow! An important, successful person wants to work with me and there’s no actual twist to that. It’s just like, Oh how wonderful! What a lovely chance to make something that the people might like.