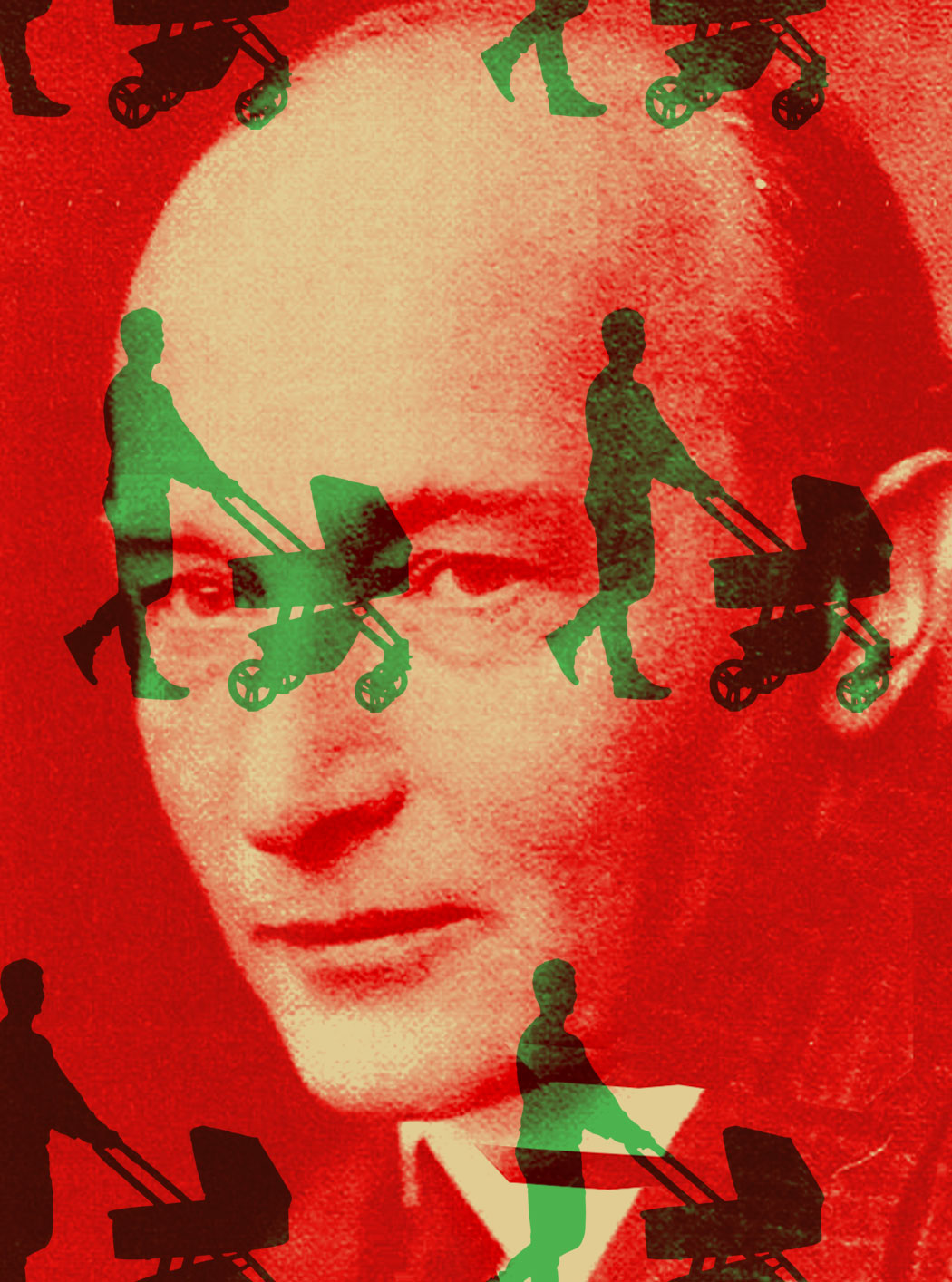

Robert Musil once shared a street with James Joyce, though the two rarely spoke; it was the late 1920s, and both were expat writers in Trieste, separated by a few doorways. The fact that one of these writers did the work of situating the other nagged Musil for most of his career. He was often bitter about his lack of fame. It wasn’t until after his death in 1942, and the publication of his unfinished masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities, that Musil would be regarded as one of the twentieth century’s great modernists. With chapter headings such as “A chapter that may be skipped by anyone not particularly impressed by thinking as an occupation,” the novel is an achingly funny work of metafiction; more overtly ironic than Joyce, Proust, or Woolf, though every bit as erudite. Of the group, Musil is the writer who prefigures postmodernism in all its schizophrenic splendor.

The Man Without Qualities tells the story of Ulrich, an aimless, ex-mathematician who finds himself on a committee tasked with commemorating the jubilee of Emperor Franz Josef. It’s the waning days of Austro-Hungarian reign—the eve of World War I; a truly mordant undertaking. It’s a world Musil knew from experience.

Ulrich traverses the bourgeoisie milieu of Vienna, mentally swinging between Übermensch and Letzermensch. There’s love, politics, and tons of Nietzsche. A rich cast of characters surrounds Ulrich, vividly described by a detached, omniscient voice (if you can imagine Thomas Mann inserting himself as the central character in The Magic Mountain, it might be an approximation). The novel is composed of short chapters, some plotty and filled with domestic drama; others that take a high-altitude survey of the mechanics of culture. Occasionally there are sections that stopped this reader short—paragraphs with such philosophical profundity that the text seemed to articulate the very conditions under which I found myself struggling.

I have a two year old named Lilly. She’s a wonder. In the months before her birth, my partner Robin and I left behind the restaurant-rich blocks of our cherished neighborhood for a small apartment on the southwest corner of Prospect Park, Brooklyn. The park added substantial acreage to our 650 sq. foot lot.

The summer before last, when Lilly was nine months, she turned fussy after waking. I began taking her for morning walks that stretched into hours, weather permitting, as we made our way along the pebbled path at the edge of the park and then deep into the expanse of sprawling lawns within.

Gradually, and then all at once, I saw the replicas: white, vaguely hipster dads who mimicked my every move. Earbuds in, one hand...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in