“Listen to yourself. You are right about everything. Be a survivalist, because we’re all going to be fucked soon. Avoid debt, which is a way of trapping you in the system. Learn more skills than anybody, be a bigger nerd and read more at the library, become friends with more weirdos, and put rich people down and make them cry if you can. You don’t need them. Your teachers are poor and confused, so they are your allies. Try to buy a farm with them, and make noise music there with amplified potatoes and drop acid on full moon nights.”

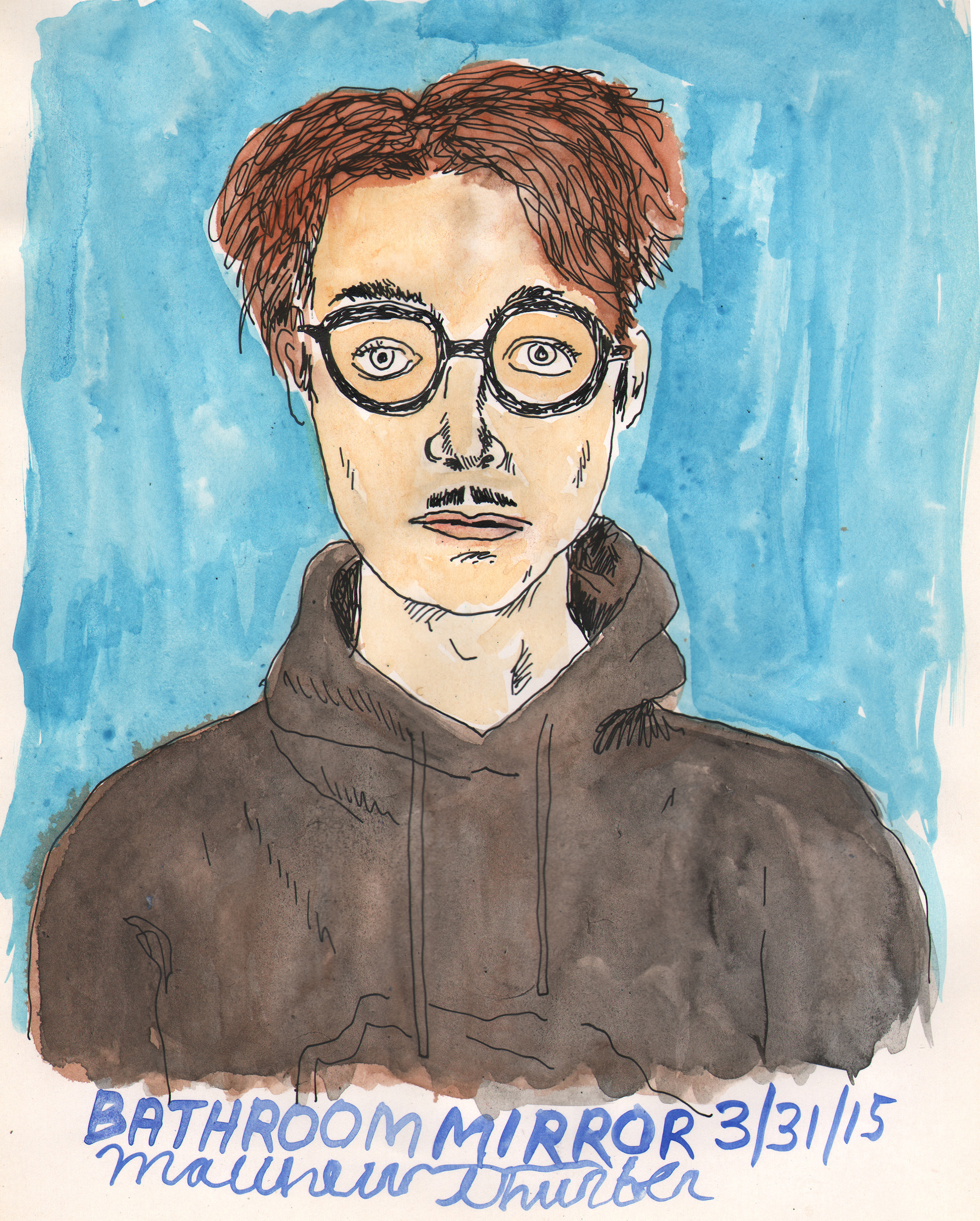

Sundry Methods of Matthew Thurber’s Creative Process:

Throwing a sponge at the wall

Recognizing that his belly button looks really good

Hate-watching interviews with Jeff Koons

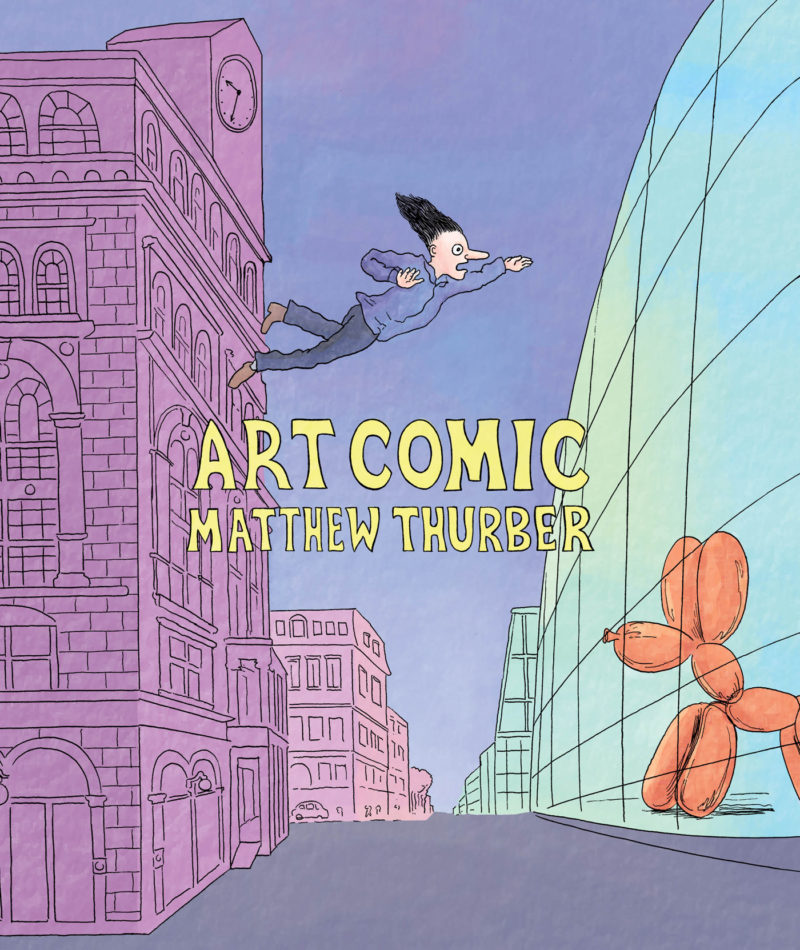

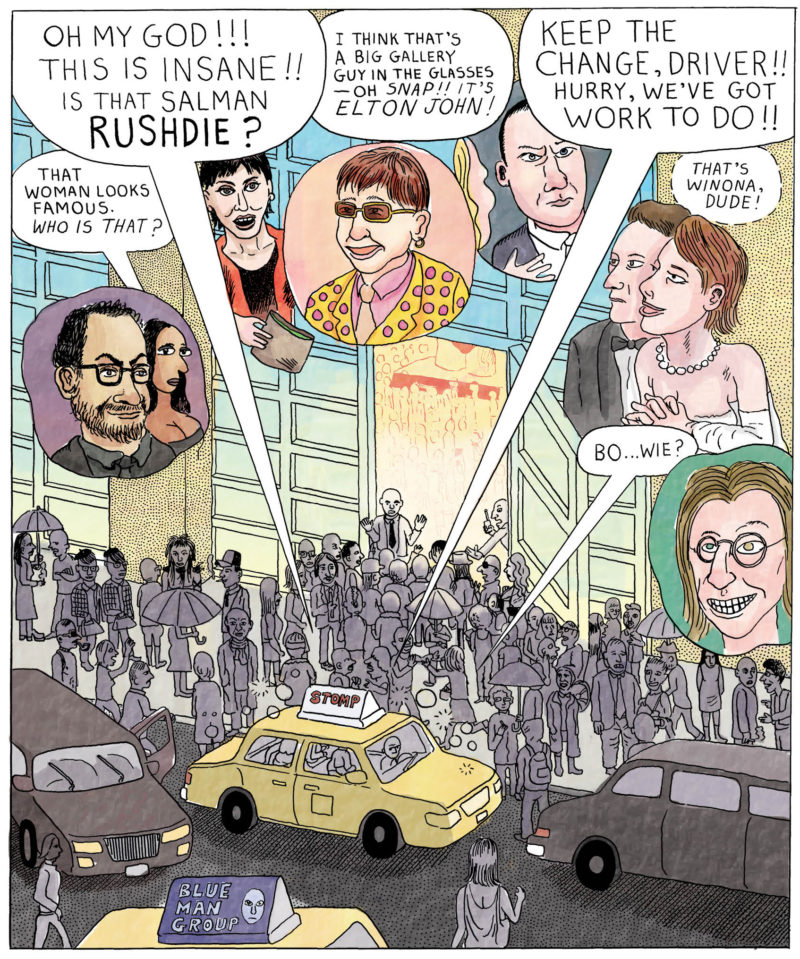

Art Comic (Drawn & Quarterly, 2018) keeps a straight face of bemusement with its tongue puncturing through its cheek as it follows a compilation of memories and opinions, ideas and jokes, fantasies and nightmares from multidisciplinary artist Matthew Thurber, author of the graphic novels Infomaniacs (2013) and 1-800-MICE (2011). Based on his time in New York City since the late 1990s, Art Comic is a series of vignetted storylines that cross-weave characters and ideals in the same pseudo-real semi-fictional world of Art, galleries, museums, celebrity, art school dogma, fantasy, and dystopia. Studded with the recognizable names of artists and galleries, stores and bands, the book is a time capsule laced with the clarity of hindsight: what brought us to turn art into a market and why do we all keep buying it? Without the coyness of self-conscious hesitation or shyness, Thurber not only succeeds in making a remarkable collection of visual drawings but has created a mirror in which we can see (and choose where to place) ourselves in the absurdity that exists as the molten core of the art world.

—Shelby Shaw

THE BELIEVER: How would you describe the history of your art career right now?

MATTHEW THURBER: Oh gosh. I went to art school but had interests that were not being addressed there. In my first year out, when I had started to work at the Met as a day job, I threw a sponge loaded with ink at four pieces of paper on the wall. One said music, one said comics, one said film, and one said writing. I think those were the four categories. I was like, “Whatever I throw this at, that’s what I’m gonna work on for the next ten years. I’ll work on each one for ten years.”

BLVR: A Forty-Year Plan.

MT: It was a forty-year plan, exactly, but I didn’t know which one to do first. The sponge landed in between two of the options and I don’t remember which ones they were. I might’ve just ignored the Magic 8-Ball and started to do comics in 2001 and hybrid music performances in 2003.

BLVR: Have you always been interdisciplinary in your art practice?

MT: Yes, always, starting with mix tapes and zines, a collage, kaleidoscope, cabinet, and cornucopia of found and dried creatures caught and united in one fishing net. For the same reason I always loved composers like John Zorn cutting up between forms and dynamic collage compositions. One time I stared at the word “SYNTHESIS” printed on a piece of construction paper pinned to the wall. It conjured the image of an Apple II+ computer erupting out of a volcano and the word enchanted me. I am aware that artists repeat themselves for other reasons due to market pressure. Like Morandi. Or anyone who likes to play with filling blank pages or canvases over and over. Constraint versus engulfing: are they opposites? I refuse to settle. What a nightmare word. Following obsession across the seven seas and trying to invent “New” genres is not opposed to the honoring of tradition, the practicing of forms, and memorization. Both ends of the spectrum obsess me.

BLVR: How has that manifested in your art practice in the last twenty years as an adult out of art school?

MT: I’ve had perhaps more adventures than successes, but I’ve had the opportunity to, through comics, do international shows and work on multiple books that I feel really proud about. I made comics when I was twelve, but then out of school I started making comic zines in 2001 and submitting to Paper Rodeo. So I was trying to push comics and get into anthologies in the early 2000s. A couple of big books have since come out, and swirling around that are all kinds of weird little gigs. Some of them are illustration jobs, some of them are performances, some of them are, I don’t know what—installations? I think because of the nature of my work intentionally being hybrid, or hard to pin down, or hard to commodify, it’s been an all-over-the-place career. I’ve taken as seriously the idea of playing saxophone in a weird Muzak band as doing drawings in a gallery, so I have a different evaluation process for success, as well as for what defines my “career.” And yet, the comics have always been strong. I feel like in that world, it’s always been a place where I’m understood. I’ve seen comics as a way to put my writing out and I think the writing is stronger than the drawing. So fine, comics have worked out. And it maybe seemed funny to do autobiography when I started on Art Comic. I think once you hit your late thirties, you start to get flooded with memories, and maybe then you start to look into your belly button. And your belly button starts to look really good.

BLVR: Art Comic blends the recent past (like Cooper Union in 1999 and Kim’s Video store) with surreal malchronology (such as being picked on by Robert Smithson) into a series of fluid sections representing the same world of characters. What was it that compelled you to take up the task of starting, completing, and publishing Art Comic now?

MT: The initial slapstick vision was to pervert my memories of my first years in Cooper Union in New York into the “funniest comic ever.” Years of observation embedded in the art world, but as a cartoonist without a financial stake in the game, gave me the experience. I realized I could “destroy the art world,” psychically, using humor. The form of the Graphic Novel, standing outside the walls of the Gallery-Museum-Auction House-Industrial Complex, was a perfect catapult. This immature reformist urge carried me through the comic book series as it evolved and morphed over the four years it took to complete. Meanwhile the art market’s bubble continued to inflate with distorted oily reflected images of hope and success for all young graduates exhaled into the bubble from the lungs of the educational system. The project eventually downshifted into a balance between responsibility towards the characters and a need to create an agitprop statement against art becoming an abstract capitalist valuation system.

BLVR: How long had Art Comic been a project you were working on? Was it deliberately setting itself up to become a book from the start?

MT: I worked on it from 2014 through 2018. It was released as comic book issues in five parts from Swimmers Group. Serialization was important to me, as I could not delay speaking and I wanted immediate feedback on the work. I could also present letters and essays around the margins of the story. A zine is more like a newspaper. In its final form as a book it is a collage of different impulses and strategies. I don’t know if I could ever just hide away and work on a collage for five years… the glue would get too dry.

BLVR: Were there any particular zines or comics that inspired you specifically while working on Art Comic?

MT: The pacing and compression of Tim Hensley’s work, especially his book about Alfred Hitchcock [Sir Alfred No. 3], continues to be a shining example of what can be done in the form, and Sammy Harkham’s epic scope and period detail in his “Blood of the Virgin” story was continuing to come out as I worked on the story. Carlos Gonzalez is always making work that is steadfast and traditional but also totally experimental and surprising in its narrative. Lale Westvind’s comics impress me with their vigor and pacing. But really I spent more time during the making of this book with William Wegman’s early videos, Salvador Dalí’s autobiography, books like True Colors by Anthony Haden-Guest, and hate-watching interviews with Jeff Koons where he talks about removing narrative and the artist’s hand out of the process of making art.

BLVR: Are any of the scenes or characters autobiographical?

MT: I work with themes of reality and identity. I’m not sure if it matters what is “real” because of the way that memory and reality mush together. The point is that stories exist as a sea-bed of mythology that everyone—not only people living in New York at a certain point in—can recognize as potentially real. The authenticity of memories is something that people can take to the bank in certain conditions. It becomes part of their story, even part of their resumé. A large part of the valuation of an artist comes from the acceptance, the usefulness, and the constant re-telling of their story. I am interested in how memoir can be real and not real at the same time, and this book is more of a hallucinated memoir. The reader may wonder what was experienced, what I just read about, and what was completely made up out of East Village Cheese. I assure you that I hung out at Passerby, Mudd Club, the Cedar Bar, Max’s Kansas City, Florine Stettheimer’s salon, and did laundry in McDermott & McGough’s bathtub… and I remember Harmony Korine trying to sell back all his girlfriend’s electroclash CDs at Kim’s. “All art is autobiographical, the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography,“—Fellini.

BLVR: Matthew Barney is threaded throughout the book, mostly as the art student Cupcake’s ultimate übermensch artist—and yet it’s this fandom that makes a subtle mockery of both of them. Why did Barney end up being the major deity figure you chose to have worshipped? If you wrote Art Comic to take place today, who would you choose as Cupcake’s idol?

MT: I adored [Matthew Barney’s] work in college and still am very influenced by it. Barney works with reality, converting aspects of people or things into a personal logical system. He has spoken about attaching his own work to a “host body.” Maybe with this in mind, I used him as a figure in my own system of critique, which portrayed him as a figure in which he has lost control of the Cremaster cycle to real estate developers. I’m using him as a metaphor. It’s because he is the ultimate figure of control, of art stardom, of masculinity, or competence, of force. I punished him by having him try to make comics using a “drawing restraint.” His work is so expensive, and really unfunny—the opposite of humor. I don’t know if I can think of it as subversive. Or guided by a philosophy, like Salvador Dalí, who I find more generous as a thinker. I was an extra in River of Fundament, I once did stand-up comedy and told jokes about Barney at a comedy club at which he was present and I went up to him and babbled like a doofus and was stoned and asked him what he was working on and he said “sculpture.” I considered titling the book Matthew Barney. Today maybe Cupcake would idolize… Jacolby Satterwhite? Five years ago, Ryan Trecartin? Seems like there’s always an übermensch out there causing an anxiety of influence for young artists. It’s generational, and who weighs on you is different for everyone, but Barney really is an incomparable figure.

BLVR: Were you ever concerned about including any real figures? Were there some plots and characters you had sketched out but decided not to publish?

MT: Satirizing this artist or that artist seemed like going after low fruit. I wanted to talk about the art world system in general. The inclusion of real people is to think about what they represent in that system. At one point I had Salvador Dalí enter the book as a kind of guidance counsellor. I took that part out, because I was disappointed by my representation of him. In a way there was too much to say about surrealism and philosophy.

BLVR: There’s a vague plot line throughout the background of Art Comic in which “The Group”—an exclusive, and elusive, club of established artists—employ art school instructors to purposefully fail and discourage their most promising students from going on to become the next generation of great artists. I love this plot line because it’s a very simple and logical way of understanding the absurdity surrounding who becomes a famous Artist, and when. It makes me think of sections of the book more as fables or fairytales to teach anti-shallow-minded morals, especially when you introduce “The Free Little Pigs,” who are guerrilla swine out to sabotage the narrow perceptions of institutionalized art. Can you talk about creating these two character sets, The Group and the Pigs?

MT: Conspiracy theories are fairy tales, which provide easy solutions to complex situations. I don’t think the situation is very simple when it comes to capitalism and idealism in the art world. I like to describe that world as a mist that when you are inside, you can’t perceive clearly. The tendency to feel that someone is oppressing you or preventing you from achieving what you want to, is a real feeling. Actually, the problem is built into the structure of the system, and everyone who participates on any level is sharing the blame for the inability of most artists to make a living off their work. Also, nobody is ever satisfied, and nothing is ever enough. Why is this? Why is the Guggenheim an upward spiral?

The Free Little Pigs are a fable about a displaced anarchist collective and their interporcine struggles. I was thinking about groups like Survival Research Laboratories and how to discuss the ironies around creating difficult or confrontational work. As the Pigs try to remain pure and make art that is pure destruction and violence, they become notorious and the art market absorbs them back into its system. Capitalism always wins and even the spectacle of its own destruction can be marketed, branded, evaluated, put on the cover of Artforum.

BLVR: Do you think there is any social or economic solution out there, lying dormant under our noses, that we just haven’t embraced yet (and maybe never will), like an art world in which there is no buying or selling market, or where there is no system of values based on review bylines and gallery names?

MT: I believe that art is a spiritual process. And I really only care about folk art.

Every aspect of the structure of one’s art making can be considered and designed in a way to prevent it from supporting the investment economy. This may mean staying poor. That’s okay. It’s not naïve. Integrity is more important than money or “happiness” or “comfort.” Sacrifice is an act that contains a magic power, and is a fertilization ritual that makes the crops grow. Do you really want the respect of the inherited wealthy who tamed the city? They can afford studios in New York, therefore they are artists? They have more familial connections, so gallerists from the same class trust them and give them shows? They slide into invented positions of authority like curator or advisor, inserting themselves between the artist and the people, taking their cut? They have nothing on the real freaks. And freaks are who make real art. Like William Blake, Jack Smith, Maya Deren, Edward Gorey, van Gogh, Rammellzee, whoever you believe in and made you want to make stuff in the first place. It’s important to be really critical, sassy, to be able to say “I think you are worthless, meaningless, fuck you.” I’m just talking to the poor kid who maybe wants to go through the system, and who is talented, and who accepts the judgement of their peers. Listen to yourself. You are right about everything. So be a survivalist, because we’re all going to be fucked soon. So what you know how to do, and what you mean to other people, will be the things that keep you alive. Avoid debt, which is a way of trapping you in the system. Learn more skills than anybody, be a bigger nerd and read more at the library, become friends with more weirdos, and put rich people down and make them cry if you can. You don’t need them. Your teachers are poor and confused, so they are your allies. Try to buy a farm with them, and make noise music there with amplified potatoes and drop acid on full moon nights.

BLVR: Who is your intended audience for reading Art Comic? Have you received any negative or angry feedback that surprised you?

BLVR: Who is your intended audience for reading Art Comic? Have you received any negative or angry feedback that surprised you?

MT: Well, I don’t just want “art people” to read it. I think anyone who likes jokes, images, or is interested in memoir, will like it. Really the art world is a metaphor and resembles any other bubble, like the Tulipomania that overtook Europe in the 17th century or the housing foreclosure bubble in the 2000s.

I haven’t gotten any shit for the book so far. Making my critique in the form of a comic book will keep it in alien language to 99% of the people in the art world who are all generally illiterate.

BLVR: With so much tongue-in-cheek—or maybe trauma—from being submerged in the art world(s) for decades, what’s become your daily dosage now? As someone who works on multimedia projects, it seems like the illusions of art-star gallery dreams would be far from concerning you.

MT: I’m interested in alternate systems of art making and sharing outside the art monoculture. I will go to galleries, but why go to a store where you can’t afford anything? To me that just means “This is not for you.” I feel very strongly that different models are needed. I feel the same about schools but I work in school so I have to go to work and I’m putting more energy in that direction. I feel positively about the DIY music, performance and art scene in New York. I’m finding a lot to think about through reading and talking. I like libraries and visiting friends’ studios. Thinking you have to see things is a burden. I would rather make art than keep up with every single fucking gallery show. I want to put my energy into supporting things I care about. Museums are disappointing and seem incapable of being radical spaces. I’d rather look at squirrels in the park than go to MoMA.

BLVR: Earlier you described the Art Comic project as an “agitprop statement against art becoming an abstract capitalist valuation system.” How do you balance the satires and repulsions you’re working with in Art Comic simultaneously with your work in schools? Can you talk a little more about teaching (in a formal school setting) from your perspective?

MT: I’m trying to be as idealistic as possible in my teaching. I teach animation and comics. Comics are completely lo-fi, you’re just talking about techniques and ideas, pen and paper. This is great for me: it’s a folk art medium I am teaching. But when it comes to animation, the classrooms are usually set up like little office cubicles. There’s no desk space, just a screen, and you are expected to use a pre-made suite of Adobe software. There’s absolutely no reason why animation has to be taught with the tools of Big Tech. It’s an art form based on exploiting the biological phenomenon of persistence of vision on the retina. I don’t see why everything has to be made with tools handed out by these corporations, and seen on their platforms, which will just further the extinction of any artistic autonomy. So for instance, I am trying to teach how to make animation without using computers. I’ve become interested in going back to 16mm film, and flipbooks, and not using cameras. It’s a new genre I am half-jokingly calling “ANIME POVERA.”

BLVR: You recently made an hour-long 16mm film about Mars, called Fleegix, which you started and completed after publishing Art Comic, then took on tour around the States and into Canada. Was that your first foray into filmmaking?

MT: No, I had more or less studied film and animation at Cooper Union, and there are some references in Art Comic to the early films I made, with the characters Boris and Cupcake shooting a vampire 16mm film on the street. That was definitely a primary art form for me when I was in art school, and I had always made videos. The weird thing with the Fleegix film is that I don’t think of myself as a filmmaker. I guess I think of myself as just this person who makes all these different art forms.

BLVR: Had you always been exhibiting your videos or putting them into settings for people to see? Were you screening them?

MT: Yeah, here and there. I did a residency and made these ten movies in a week, a movie every day for a week. They’re kind of a part of the “Thurber Oeuvre” but comics just became such a preoccupation that I didn’t really work on the movies anymore. I feel like you have to choose whatever’s primary, and the Fleegix film became primary for me in the last year through a backwards way in which I thought I was making animation, and it ended up being a live-action film that ended up being a performance. I don’t really have that much control over these things, ideas turn into forms that I don’t know they’re going to take when I start working with them. I just cultivate them and let them become whatever they want to be. That’s the way that I make work, and that’s why it takes such weird forms.

BLVR: Where does this leave you now?

MT: I’m probably going to work on a musical next, about the same preoccupations: the past, history, capitalism, people, alienation. I’m probably going to make a live-action musical mumblecore film about capitalism.

BLVR: Is mumblecore the untapped genre for the “Thurber Oeuvre”?

MT: Exactly! It’s like saying I’m gonna make a disco album. People would say, “That’s so dumb that it might just work.”