Early on in Horizon, Barry Lopez’s urgent new book, he admits to feeling anxious about the future, about what will become of us during the long, dire unraveling of global climate change—“with an indifferent natural world bearing down on us” amid our deepening cultural divides. Which isn’t to say it’s a doomsday book. In the larger scheme of Horizon, climate change is a minor subplot. While it may be true that we should all be hoarding canned goods and firearms and building heavily fortified compounds far above sea level, Lopez doesn’t traffic in dystopian despair. He’s trying, partly for his own sake and partly for ours, to understand how we got here and what, if anything, we might do to save ourselves.

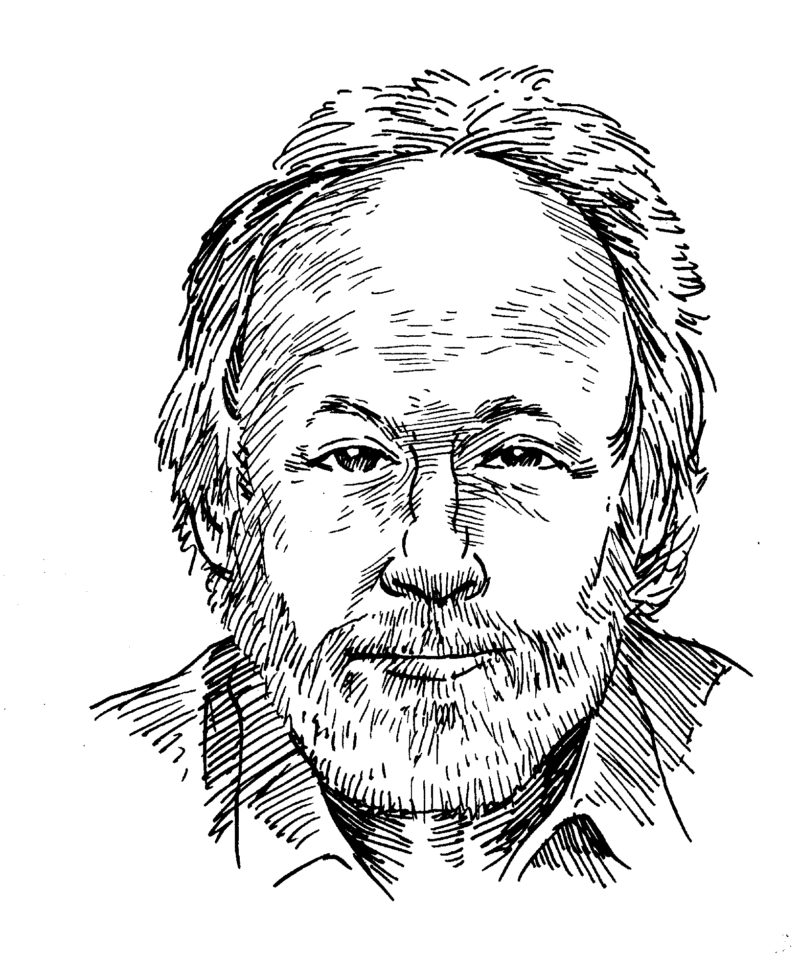

In a career spanning five decades, Lopez has given us a steady infusion of sanity and bigheartedness, no matter his subject. Known best for two early nonfiction works, Of Wolves and Men (1978) and Arctic Dreams (1986)—the latter a winner of the National Book Award—he’s also an unsung master of short fiction (Winter Count, Field Notes, and Light Action in the Caribbean, to name just three slim wonders). Such ambidexterity, it goes without saying, makes him a rare bird in contemporary literature.

At the root of much of his writing, both fiction and non-, is a tension between the natural and the domesticated worlds, between rural and urban landscapes, and in our attempts to control nature while being part of it. Take the narrator of “Winter Herons,” from his 1981 story collection Winter Count, a bumpkin transplant to Manhattan who gets struck dumb one evening by a seemingly innocuous sight: “The young ginkgo trees spaced so evenly along the edge of the avenue seemed like prisoners to him, indentured ten thousand miles from China.”

Lopez spent his formative years in California’s San Fernando Valley, during the last wild days of the Los Angeles River, before it was paved over. By his telling, he was outdoors all the time, inhabiting what he calls a “borderland” between farmland and the rural fringes that was just starting to succumb to industrial sprawl. At college in the Midwest, he began taking weekend road trips with a friend—impromptu, open-ended journeys fueled by the vaguest sense of where they were headed and why, and by a desire to simply go and see what was out there. In the fifty-odd years since, Lopez has rarely stopped moving.

Horizon is, among other things, the culmination of a lifetime of intense travel, or “sojourning,” as he calls it—to Antarctica, the Canadian High Arctic, Tasmania, the Galápagos Islands, Namibia, Tierra del Fuego—the kind of long-haul globetrotting that, as Lopez would be the first to admit, exacts a heavy carbon toll. It’s a beautiful, sorrowful autobiographical epic that feels like a final reckoning of sorts: with the difficulty of living a moral life today, with our estrangement from nature, and with the spectacular mess we’ve made of things. There’s not an iota of righteousness or judgment, but instead, abundant reminders of human possibility in desperate times.

“I wanted to write something about the peril we’re in and to take a position as a narrator of being implicated, as we all are,” Lopez told me. “But as dark as it is, there are still things we can do.”

At seventy-four, Lopez has slowed down a bit. He spoke to me from his home, on the McKenzie River, in western Oregon, where he has lived for forty-eight years. Although his voice betrayed no fatigue or pain, I nevertheless kept thinking of an unnamed protagonist from Field Notes, who, after making a death-defying trek across the Mojave Desert, arrives at a headwaters, badly parched and winded, and says: “I did not anticipate the ways in which I would wear out.”

—John O’Connor

I. A NATURAL ARC

THE BELIEVER: Your new book, Horizon, is far and away your most autobiographical. Until now you’ve been pretty careful about staying out of the narrative lens. Why the sudden change?

BARRY LOPEZ: I don’t know. For a long time I guess I felt that the self wasn’t all that interesting a thing to write about. It wasn’t illuminating, and illumination is a huge part of what I think is important about writing nonfiction. So it’s natural for me to have never been self-celebratory. When I find self-celebration in a piece of writing, I recoil. I think, We’re not going to get very far with this. I resented a lot of first-person stuff I read in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, which was just rubbish. There was nowhere for the reader to go but the writer’s mind. The effort there was to control the reader and subconsciously deny that the reader was an equal. I love to bring something that’s been ignored or marginalized or disparaged into a light that shows some measure of its holiness, its humanity. You know: we’re a bumbling bunch of simians, but there’s an aspect to us that’s endearing. We have a world so full of derogation and dismissal. It’s important, if you have the opportunity, to say, I was staggered by the quality of this person’s compassion in this terrible moment. You wouldn’t use language like that, of course, but that’s what you’re trying to track down.

BLVR: The implication being that we’re in an age of oversharing, that writers should think twice before writing about themselves?

BL: Most people don’t have very much to share. You know the longtime coach of the San Antonio Spurs, Gregg Popovich? I watch a lot of basketball, and Popovich is of another order than a lot of these guys. He has developed some of the most interesting dynamics on the court. When you watch his teams play, you see a level of cooperation that’s enthralling. I’ve often thought of him as a standup guy because of his objections to Trump, and the way he expresses those feelings. He was asked once about the NBA draft and what he looks for in a player, and he said, “We’re looking for people [who have] gotten over themselves.” I think to develop as a writer, you’ve got to get over yourself.

BLVR: How, then, did more of your personal life make it into Horizon?

BL: There’s a natural arc at work. It takes a while not just to accumulate experience but to develop a point of view. If you start with a book like Of Wolves and Men, I stayed in the background and let everybody else speak. I was reticent to say much on my own authority. My agent told me, way back then, in a loving way, “You can see the homework shining through” in that book. With Arctic Dreams, I felt like I had some experience and it was OK to say a few things once in a while, but I was still deferential. The narrator should strive to be a companion, not an authority. He’s trying to open up the Arctic world to people. The image I had of myself was of standing next to someone, explaining the particulars of what we were seeing while at the same time putting my hand on the small of their back and pushing them forward, so that they could take possession of whatever the scene was, and I would just disappear. But I didn’t want to write another book like that. I wanted to write something different, something based on an answer to the question “Why do you do this, write about these places?” At this point in my life, I’m comfortable saying what I think about something. My editor said to me, “You know, you can just own it. You don’t have to constantly apologize to the reader for offering your own view.” So with Horizon, I was willing to speak about myself, to talk about my emotional life, but of course in a metaphorical way.

BLVR: You’ve called Horizon an “autobiography of a journey… about geography, and various arrangements of space and time, that create hope or destroy hope.” Can you explain?

BL: It’s essentially an autobiography of my forties and fifties, when I was traveling very heavily, both through big cities and in very remote areas. It fundamentally changed the way I think about the world. I had begun to see, I think in the 1980s, that some kind of international awareness was coming. Not necessarily a political awareness, but an awareness of something beyond the nation-state. A lot of Horizon is about that. It’s asking the reader, in a gentle way: We’re all trapped in the tentacles of nationalism and warfare and financial collapse, so how do we get out of here? The whole idea of the nation-state is dead. It has nothing more to offer. The damage it has created, hand in hand with industrialization and capitalism, is a nightmare. What I want to say, in shorthand, is that the wrong people are deciding our future. It’s a bunch of white, educated, Christian men. We’re not going to get an answer there. They’ve given us the problem. The solution will be seen by people who aren’t in those positions. I’m talking about the kind of elders I’ve spent time with and who are steeped in two languages, who are operating in the mestizo area. They have a different epistemology. They can show us a way out, or a way to imagine a way out, so we won’t be stranded forever in depression. The mixing of cultures and races and traditions is so widespread and goes so deep—some of it for bad reasons, like colonialism—but it’s what we’ve got, so let’s use it.

BLVR: You’ve said that part of what you like about traveling with indigenous people in their home landscapes is that they’re good at noticing subtleties and looking backward and forward in time, in a sense—both at an object and away from it.

BL: Yes, they look at objects differently. And what I’m trying to do in Horizon is present this in such a way that the reader neither is confused nor feels they’re being urged to abandon their own way of seeing the world. There are two presences in the book: one is Captain James Cook, the quintessential Enlightenment man; the other is a man named Ranald MacDonald, an obscure Native American who was born at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1824. He had a Chinook mother and a Scots father. He was hamstrung socially because he was neither white nor Native, but he was determined to accomplish something. He worked on whalers out of Sag Harbor, and he got it in his head to go to Japan when Japan was closed to the West. There was a shogun’s edict that forbade the building of seaworthy ships. People could build vessels only for trading along the coasts. But these coastal vessels would occasionally get dismasted or lose a rudder in a storm and end up drifting across the Pacific and washing ashore in Washington or Oregon. One of them reached Washington when MacDonald was about ten or twelve years old. There were three survivors aboard, and when MacDonald saw them, he thought they looked just like him, like Indians. So an idea was planted in his head that these people, whom he was told came from a closed kingdom, or, as Melville called it, the “double-bolted land” of Japan, naively believed they could keep the West at bay. He knew, because of what had happened to his own Chinook people, that there was no way you could stop the Westerners. He saw what was coming and knew Japan would eventually be overwhelmed. So he devised a plan. The captain of a whaler he was on gave him a whaleboat and put him over the side in the Sea of Japan. He drifted ashore in Hokkaido and said he was a shipwrecked sailor. He was taken to the shogun’s court in Nagasaki, where he taught several members of the court to speak English. He believed that if they were going to defend themselves against Western people, they had to speak their language. He preceded Commodore Matthew Perry by six years, and Perry was stunned to find, in a closed kingdom, a court of advisers who spoke English. This was MacDonald’s doing, but he’s been written out of this history. In Captain Cook, I wanted a representative of the faltering of the Enlightenment, and in MacDonald, a character who represented—it’s a melodramatic way to put it, but—the rise of the mestizo, a person of more than one culture and language, of greater worldwide experience.

II. NOT A VICTIM, BUT A WITNESS

BLVR: You wrote a piece for Harper’s in 2013 called “Sliver of Sky,” in which you fully revealed for the first time how you were sexually abused by a family friend for years, starting when you were six years old. Was this perhaps a reason for maintaining some distance on your private life—it was too painful?

BL: Sure, yeah, I think so. It was a very painful place for me to go. From 1996 to 2000, I worked with a therapist to go back and sort out what had happened in my childhood and, if you will, get it out of the living room, give it a room in the back of the house or something like that. I knew I had to get control of it before I could write about my childhood in a way that was smart and engaging and useful to the reader. A writer friend once said to me, “The only thing I’ve ever heard that’s a criticism of your work is that while you write so respectfully of people, and there’s always a moral dimension to your work, people wonder if you understand what it’s like to go through the really horrible dimensions of being human.” That, I think, lit a match for me. I thought, Well, one day I’ll have to say, I’m just like everybody else. I went through a bad place, and here I am. But, you know, it’s just one of the things on my shelf. It’s not something that was always asking for more attention.

BLVR: Was “Sliver of Sky” what led you to start writing more explicitly about yourself?

BL: I don’t know exactly what prompted me to be more revealing. Something happened to me while I was trying to work out this thing in my childhood. I was scuba diving in the Galápagos once. One evening, I saw something in the distance that I couldn’t parse, until I realized it was sea lions caught in a net and drowning. I asked the guide, a guy named Orlando Falco, if we could intervene and go to their rescue. We were in a panga, a boat that’s a little bigger than a dinghy. Two other passengers counterbalanced the boat, throwing their weight on the far side of it and holding up flashlights while Orlando and I put our legs against the gunwale and, with our dive knives, began cutting the animals out of the net. I was leaning against him and he was leaning against me, and we were trying to balance ourselves with our shins against the gunwale, and we were nicking each other’s arms in the commotion. We were trying not to cut the animals or each other, but the sea lions were absolutely frantic. They would grab the gunwales and chew at them, trying to pull themselves up into the boat, which was always in danger of flipping over. At one point I had my knife in the air, and was adjusting my feet to get a better grip on the bottom of the boat, when—boom!—the knife was gone. It was dark. I couldn’t see where it went, so I leaned more fully into Orlando and said something like “Lost my knife.” Meaning: I’ll help you put tension on this part of the net so it’s easier to cut. I put one arm out to balance myself, and then, as I made a turn, I closed my upraised hand around my knife again. When we got back to the main boat, Orlando and I were totally exhausted, sitting on the deck, catching our breath. We noticed our shins were black-and-blue from banging against the gunwale. Something had happened between the two of us that was so powerful, and I said to him, “Did you see what happened with the knife?” And he said, “Madre de dios.” So that, of course, rang in my head ever afterward. I wrote an essay about this called “Madre de Dios,” which ended with an incident that happened in the room where I was abused, and where I saw the Blessed Mother floating a few inches above the floor one night. Writing that essay gave me a kind of permission that I had never given myself.

BLVR: Your stepdad told you back then to let it go, that nothing could be done about it. And you did. You were silent about this abuse for years. There’s a parallel with the #MeToo movement—the abused being told to be quiet, that no one will believe them.

BL: The #MeToo movement is something I feel tremendous support for, because these women are saying things that I understand deeply: no one cares, no one will listen to you, you will be called a liar, so just live with it, get over it. People don’t want to hear it, and those that should hear it want to deny it. I know what that’s like. It’s true in my own life and with other men and women I’ve come in contact with since the piece came out.

BLVR: This isn’t just about exorcizing trauma or calling people to account, it seems to me, but about seizing the narrative. You’ve written: “Not to be allowed to speak or, worse, to have someone else relate my story and write its ending was to extend the original, infuriating experience of helplessness, to underscore the humiliation of being powerless.”

BL: The idea that I’m not a victim but instead a witness really rings true for me. You always fear as a writer being explained by a single dark experience in your life. When “Sliver of Sky” was about to appear, I said to my agent, “The thing I dread is that people will now say, ‘Ah, here’s why he seems to have such compassion for the world.’” But that never came up, and I was pleased. Everyone is given something to work with, and this is what I was given. I remember when I was twenty years old, walking across the quad at Notre Dame and feeling sorry for myself because I was having so much trouble with my identity. I had such terrible impressions of myself and my sexual life. And in that moment—it’s still brilliant in my mind—I thought, Wake up! It’s a gift. Use it instead of denying it. I’ve always thought that it’s better psychologically to see it as a gift and to never get into the landscape of being a victim. I think that’s what irritates me about so much first-person, woe-is-me writing. There’s no suggestion of Hey, I can translate what happened to me for you, so that you can see that you, too, have the capacity to own a horrible experience in your life and not be owned by it.

BLVR: You don’t deal directly with climate change in Arctic Dreams, but the book anticipates it. You seemed to sense where we were headed. Are things worse than you imagined?

BL: I couldn’t judge whether they’re worse, but the most striking aspect of global climate change in the High Arctic for me is how fast the change has come. In the opening chapter of Horizon, I recount a trip I took four or five years ago when I was on the staff of an eco-tourism ship going up the west coast of Greenland and then west into Lancaster Sound. When we went into Inuit villages, the native people there were telling us, in casual conversation, about how climate change was affecting their lives: basically, Holy shit. People who don’t live inside buildings are acutely aware of what’s going on in the natural world, and these Inuit were scratching their heads about what it all meant. They asked, “Will we ever see polar bears again that aren’t starving?” One morning, we were on the east coast of Prince of Wales Island, in Peel Sound. This is an area that, historically, has always been so packed with ice in the summer that you can’t get through it. It wasn’t until modern times that, if you had an icebreaker escort, you could get through. That morning, when I got up on deck, I set my coffee cup down, looked up, and saw there was no ice in Peel Sound. None.

BLVR: I read that not a single right whale calf was spotted in the North Atlantic last season, which is a first. You get the sense from some people, the Trumpists or whoever, that Eh, it’s just a bunch of whales. Is something greater at stake?

BL: Like so many other writers, I’m trying to write about the disintegration of community and trying to create a sense of hope. Horizon is driven in part by the recognition of the subterranean fears people have when they read an article saying, “Not a single right whale calf has been spotted in the North Atlantic,” or “Seventy-five percent of flying insects have disappeared in Germany.” I know how fast these changes are coming. But what’s really scaring me, I have to say, is the rise of artificial intelligence. I think we’re in far greater danger of seeing the end of our cultural lives because of problems related to AI and the internet. That’s the most dangerous and creepiest thing on the horizon, and I think it’s going to do us in before environmental damage does.

BLVR: I had a student of mine tell me recently that if she traveled somewhere and didn’t photograph it relentlessly and post it to Facebook and have people comment on it, it was almost as if she’d never gone.

BL: I don’t think there’s any doubt that dependence on electronic communication has created a weird and terrible kind of isolation for us.

BLVR: Much of your nonfiction involves travel. Do you ever feel compelled to not write about a place, out of fear of attracting attention to it and the damage that could be done? Are we sometimes better off just staying home and leaving other places and people alone?

BL: Yes. The first time I did that was in an essay called “The Stone Horse.” I was pointed in the direction of a six-hundred-year-old stone glyph in the Mojave Desert. I found it, and there was no fence, no protection, and I thought, I cannot say where this is, and I didn’t. The next stage in my determination to protect people’s privacy came in an aboriginal village in the Northern Territory of Australia. The people there were very kind and excusing of my ignorance. They said, “We’re going up into the Tanami Desert to take care of a place that was polluted and poisoned many years ago.” In 1929, some aboriginal people were murdered by territorial police at a water hole there. Nobody had been back since. They wanted to go and, in their vernacular, clean it up, spiritually purify it. They asked if I wanted to go with them. I wrestled with it, but finally decided I couldn’t go. I’ve gotten to participate in many experiences like that. There had to be a time when I said no. Let them have the experience and come back and tell me about it, rather than have me, in some sense, push them aside and interpret the event myself, which would have been sacrilege. I’m at the point now where I’m in favor of not going places and instead making do with what I have. It’s an important turning point: to resist the pathology of consumerism, whether you’re buying something in a store or demanding that your travel agent send you to a place nobody’s ever been before.

BLVR: Not long ago you were on Ellesmere Island, in the Arctic, where you were approached by the owner of an adventure-travel company who told you he created his entire business around Arctic Dreams.

BL: That moment of disbelief was, for me, a warning. As a writer, you have the power to communicate something about places like that, and you should be very careful how you use it.

III. CHOOSING TO LISTEN

BLVR: Is it possible to reach a point of connection with the natural world, to come to know a place without extracting something precious from it?

BL: I would say the first rule in connecting with nature is to pay attention, and part of paying attention is choosing to listen instead of speaking. The most difficult part of being outside one’s comfort zone is understanding how much you’re being taught by not talking. In my experience traveling with indigenous people, nobody says much of anything while they’re on the move. Because language collapses experience into meaning, and if you do it too soon, you’ve lost all the other meaning that would’ve been there.

BLVR: Certain kinds of “travel,” of course, might be translated as “invasion,” such as that characterized by Libby and David in the title story of your collection Light Action in the Caribbean. Are they getting their just comeuppance, or is this a story about inexplicable evil?

BL: It’s not really about those two luckless people. They’re just like us. It’s what happens to us when we’re not paying attention to where we are that I was thinking about. The story is about the disintegration of the authenticity of human lives that are different from our own. We don’t spend enough time outside of our heads to understand that there are people with bad motives and guns who’re indifferent to our fate.

BLVR: “If there was a siren landscape for me in my forties and fifties, it was Antarctica,” you write in Horizon. What has drawn you back there so often?

BL: Partly the tabula rasa quality of it. There’s hardly any human history there. And I like the simplicity of it: there’s your tent, and then the rest of the world. Another thing I like is it helped me understand more deeply my connection to wild animals. I was working on a glacier once with a team of scientists and we were setting flags and surveying, and one day I saw movement quite a distance from me. My feet came right up out of my boots, I was so excited. I thought it was an animal, but it was the shadow of a distant, small flag shifting on the surface of the snow in a light breeze. When we were pulling out of our camp, a flock of seabirds came across the sky above us. We were all so thrilled to see them. It prompted a lot of thinking about how human beings long for the Other.

BLVR: Antarctica is the only continent that hasn’t been nationalized, and as you write in Horizon, “anything might turn up here, like the most sane, equitable international treaty humans ever negotiated and signed, the Antarctic Treaty.” Is Antarctica a model for the greater equity we might achieve elsewhere?

BL: Absolutely. And I’m surprised it’s not written about more often because of that quality. A lot of the things people argue for as necessary for our survival today, especially on the left—political equity, racial equity, social equity, et cetera—it’s all there in that treaty.

BLVR: Is it a writer’s job, then, to serve society in an ethical way?

BL: Yes. At the heart of any good so-called “nature writing”—a term I abhor—is the issue of social justice. You’re not writing just about birds and your time in the Atacama Desert or something. If the work’s any good, it’s also about social justice. In the late ’70s, when Of Wolves and Men came out, I saw that I was probably going to be marginalized as a writer because this was “nature writing.” People couldn’t see that the book was really a meditation on prejudice: my feelings about prejudicial relationships between races, genders, and species. That’s what I was working my way through. Here’s the denigrated—wolves—and here’s how they became denigrated. I went through that whole ridiculous thing of being identified as Mr. Wolfman. And I thought, If you want to be taken seriously as a writer, you’d better get out of here.

BLVR: I grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan, a mile or so from the grave of Edward Israel, who died in 1884 during the Greely expedition to the Arctic and whom you mention was an origin point for Arctic Dreams. Can I ask how you heard of Israel and what brought you to Kalamazoo? People don’t usually find themselves passing through the southwest corner of Michigan.

BL: I was there to read at a university, and somebody must’ve told me that Israel was buried there, and I went and saw his grave. I knew it would fit somewhere in my world. Also, I went to school at Notre Dame, so Kalamazoo wasn’t remote in my mind. In my sophomore year, I kept a car illegally off campus. Students weren’t allowed to own cars, and if you left campus on the weekend, you had to leave a card in the rector’s mailbox saying where you were going, how you were getting there, and when you were coming back. My roommate and I filled out false cards saying we were hitchhiking to Kalamazoo, when in fact we wanted to drive up to Lake Superior, across the Mackinac Bridge and around the Upper Peninsula, and then back down to Chicago. We would take these incredibly long trips of nonstop driving. We would go to Mississippi on a weekend just to see it, to be out in the world. This time we were going to go up and around the lakes. On our way into Lansing, we were pulled over by the state police and arrested for murdering a gas station attendant in Kalamazoo.

BLVR: Yikes. That’s not where I thought you were headed with this.

BL: Yeah, that’s what I like about stories. This one’s about being subjected to police power, with no phone call allowed. They tore our car to shreds looking for evidence and then sent us on our way. When we pulled out of the police barracks in Lansing, we could’ve turned left and gone back to Notre Dame and faced the music, because the Indiana State Police had gone to our dormitory in the middle of the night and created another nightmare there, or we could’ve turned right and continued on our journey. We turned right.

BLVR: “The world needs a good story,” you’ve said. Is storytelling elemental to our well-being?

BL: Yes, because forgetting contributes to the sense of disorder in our lives. It begets something like entropy. The completeness of your life is eroded by the way you forget what you mean by your life. In the process of telling a story, and also of listening to a story, the teller remembers what he or she represents in a community, and the listener remembers what they want their life to mean. After a story, everybody is functioning better. I think part of the calling, part of what I ask of myself, is: Can you comfort? Can you deal with the darkness of global climate change and all the rest of it? Can you tell this story, which is terrifying, and still find a way to comfort people? That’s the obligation of the storyteller. It’s up to you to approach the reader as someone conceivably in pain, because of the discordance of the world that person lives in.

BLVR: What were your early years as a writer like? Did you set out to write fiction or nonfiction?

BL: I really don’t know. There’s a kind of artificial divide in my life between fiction and nonfiction. Every time I did something big in fiction, the strain on my imagination was such that I was glad to get back to something I could look up in a library. Now, with Horizon finished, the thing I’m most eager to get back to is a set of some fifteen short stories that are mostly in first draft. I want to write something where I don’t have to check everything, and not have to work—if you understand the way I’m using the term—in a rational way.

BLVR: Perhaps this is a strange question, but you’ve been writing professionally now for fifty years. Do you feel like you’ve sacrificed anything for a writing life?

BL: It’s a very painful question. The word sacrifice romanticizes the life a little bit. But what you sacrifice is good relations with your family. Somebody like me is always gone. Even when you’re home, you’re gone. I tell this story in Horizon: I had an atlas that my mother gave me in 1951, when I was six years old. I was into it endlessly, and because I didn’t want to write in the atlas, I took tracing paper and colored pencils and put the tracing paper over the maps and drew the routes I was hoping to take one day, from Cairo to Cape Town, that kind of thing. Years ago, I went back to the atlas, which I hadn’t looked at in thirty years. I’d completely forgotten about the tracing paper, and when I opened the book and found these pieces of paper, I realized that I had actually made most of those journeys. There I was, a kid fantasizing about travel, and then as a forty- or fifty-year-old finding that I’d gone and done this. I had such a fixation on the physical world as a kid that I re-rigged my closest so I could fit a school desk and a globe in it, and pinned maps to the inside of the closet door. I had a little gooseneck lamp. That was my version of a tree house. From there came this sense of wanting to get out of the house. Out, out, out! As a kid in California in the late ’40s and early ’50s, living in the San Fernando Valley, the locution was “I’m going outside.” It didn’t mean outside the house. It meant outside the familiar. To “go outside” meant to go out into the Mojave Desert, where the big conversation for me was just beginning to happen.