There are currently 605 items saved in my Amazon shopping cart. Books, supplements, appliances, shirts, boots, tools, etc. Some items appear several times, at once both singular and plural. Others I already own “in real life”, yet they continue to appear in the cart, to persist there as though I can’t quite possess them completely, as if some essential quality or Platonic ideal remains permanently withdrawn and best expressed by thumbnail. I take a sample from an evening scroll: Pale Fire, A Moon Shaped Pool, Methyl B-12, The Death Ray, Pet Naturals Lysine Cat treats, The Emotional Incest Syndrome, The Old Weird America. Time is embedded in this lyrical selection—like a core sample. I read a certain history of a certain self—a brief constellation, a legible compression—and a fragmentary image of personhood tips into the foreground then recedes again, leaving a charged residue.

The other night I added up the total cost of the items in my shopping cart. I really had no idea what to expect, so felt ambivalent about the sum: $11,510.45. I’d be hard pressed to fill a shopping cart up with that much value in the physical world, although that probably wouldn’t be too difficult to figure out how to do, especially in New York City. It took a while to add up, maybe an hour of scrolling and tallying, getting a little bit lost in a kind of shopping cart nostalgia along the way: I remember when I added that to the cart. That’s when I was interested in Alchemy, and there’s when I felt like I had to catch up on all of that Hellboy that I missed. There’s a stretch of ambitious adding-to-cart including books by Giorgio Agamben, Jean-Luc Nancy, Alain Badiou. These are manifestations of an anxiety about my own incompleteness: intellectual, cultural, spiritual etc. The digital shopping cart is a palliative—an avatar of my improved future self, the data-spirit of that future self made tantalizingly present in that clicking—add add add: continuity of self-resemblance and its commensurate dollar value.

The digital shopping cart is a charged space (pun intended), a crucible for the alchemical transformations of consumer selfhood, and a gateway into an infinite commons. Amazon.com may be the marketplace of choice for many consumers these days, but it’s more than a utilitarian site for transaction: it’s also a place of leisure, a theater, a labyrinthine public garden, a compulsive amusement park, a hazily-bordered city to detourn within, and a ceaselessly reordering wasteland; it’s a site where the salvage of self-image is organized via impulse and choice. We roam in regions of e-commerce as digital ghosts, invisible to each other in these public places of private gathering. The shopping cart icon is the portal through which we engage spaces of various exchange to record and construct desire: an ever-accumulating landscape of urges both frivolous and dire.

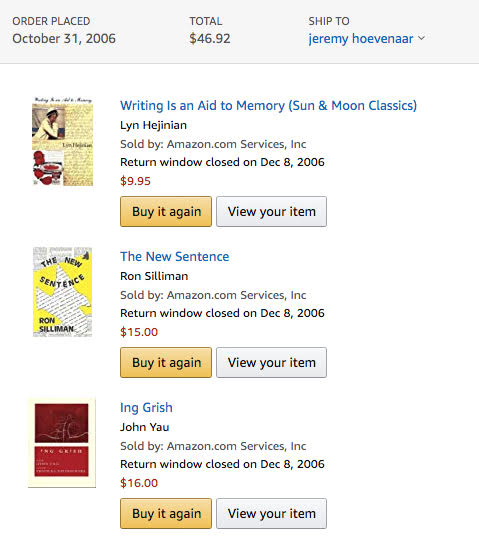

I’m somewhat ashamed to state publicly that I have 605-and-counting items in my Amazon shopping cart. I’m not sure why I feel this way; I don’t know what normal is when it comes to digital shopping carts. When I’m feeling particularly depressed, I might look back through old order histories as though they were family photo albums, as if I could regain or clarify certain of my own contours by seeing a lineage of purchases. This is a form of self-tracking. I possess, if possess is the word, and I think in some ways it is, far more potential objects in my cart than I do photos of family and friends. I’m more likely to look back at my first Amazon orders than I am a photo album.

The first family portrait is from 2006, when I was studying poetry in graduate school—I ordered Writing is an Aid to Memory by Lyn Hejinian (author of My Life), The New Sentence by Ron Silliman, and Ing Grish by John Yau. Seeing these three items posing together causes a brief and bright fluorescence within me of the hope and trepidation of early graduate school and the excitement of discovering these poets—a bit of Proustian immersive vivid-recall, shopping carts and order histories a true Memory Palace.

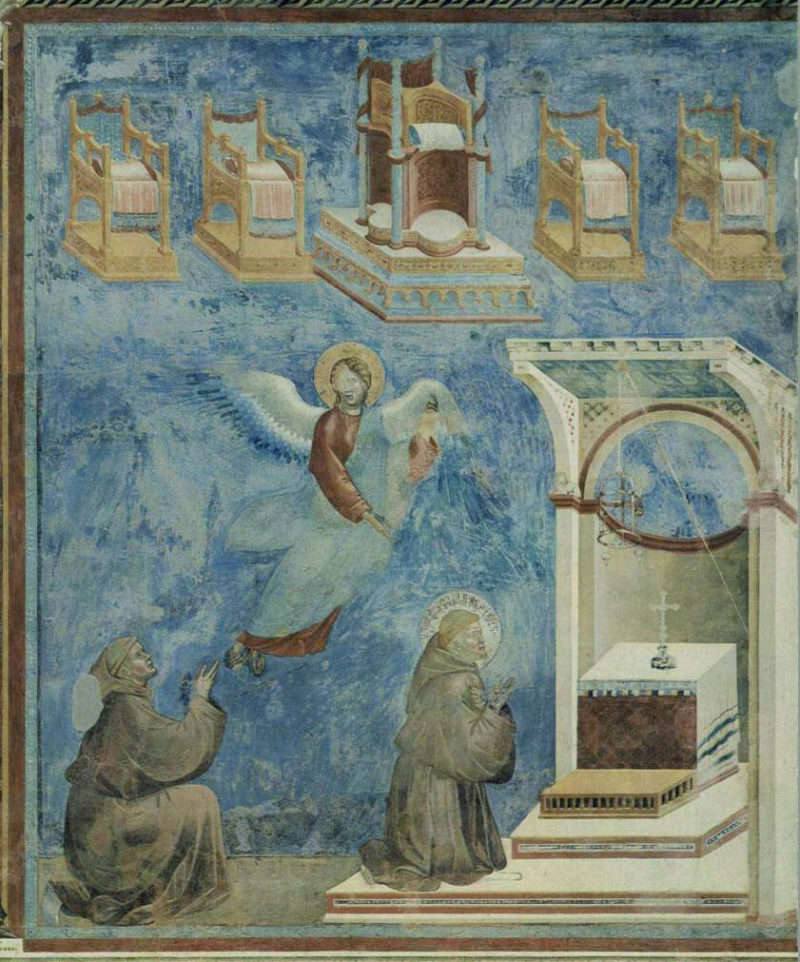

I had the good fortune to see a brilliant friend’s Instagram post recently wherein he used the Greek word Hetoimasia—the prepared throne. This ancient symbol turns up in the iconography of various religions over the last several thousand years or so and comes to represent the vacant seat made ready for the Second Coming of Christ. So of course now I’m thinking about the digital shopping cart as a Messianic space, which only makes sense. Threshold between worlds, the kingdom of heaven with free shipping, automatically renewed. Amazon Prime, primum movens, the unmoved mover. When there is so much available to want, and where this wanting is also a wanting to be, we are always bereft and waiting for the return or advent of wholeness. The cart is simultaneously an engine for an ever-further fragmentation and a reaching for wholeness. Numinous. The throne both full and empty, absent and present. My computer remembers my password for me. The door to the living mystery is always open, even when it’s closed.

I fully expect that, in the near future, experience itself will come to resemble some unholy anti-commons hybrid of Amazon and Facebook. It’s possible that it already does. Much remains unclickable, but for how long? Addition, augmentation, and and and. How often are we together in this space, not seeing each other but captured every instant by algorithms, returning to us new mythologies, morphologies and distortions of self-image? Have you read China Mieville’s The City and The City? Two cities overlap and the citizens of each must not acknowledge those of the other. It feels like that—we’re living together in separate cities infinitely layered, mingling in unseeing and unseen proximity, clicking ourselves into greater coherence. How can we breach this invisible barrier? Maybe we’ll finally meet in the flesh at the mailbox.

Another contemporary commons: the open world multiplayer video game, Fortnite. I tried playing this recently, curious about the sense of freedom it seemed to promise, and was speechless when my goofy avatar stumbled across a shopping cart. It seemed to serve no discernible purpose. I pushed it around, enjoying the images, the way the cart looked against those landscapes. There was recently a kind of scandal around this shopping cart: players were using it to exploit a glitch that enabled them to move around underground, below the surface of the map. How wonderful, I thought: the cart empowers one to cross through a threshold into a subterranean autonomy, a digital interstice, a secret place outside of accepted borders.Where’s the scandal in that, I wondered. Then I discovered that mostly people were exploiting this glitch in order to kill other players from an untouchable vantage point. Killing being kind of the point of this commons.

In Fortnite the cart seems to have become a kind of character, a proxy for weird possibility. You can fall from a great height in the cart and land unscathed; it becomes an extension of the avatar that is an extension of the player.

Seeing images online of players riding around and flying through the beautiful blue Fortnite sky in their shopping carts fills me with a longing to sit in my Amazon shopping cart and explore some luminous scape with a new autonomy; ensconced in that borderless threshold womb along with all of my potential purchases.

When I first began working on this essay, the subway station at 14th St and 8th Avenue had been colonized by advertisements for Jet.com, a new e-commerce site owned by Walmart.

The distinctly fine-art informed adds depicted commodities artfully photographed in odd or amusing pairings and named for their purchasers, as though they were portraits. Both still life and portrait. Is this still life? Our carts are different here. Uncommons.

The digital shopping cart is a threshold containing countless thresholds, the boundaries infinitely elastic, the items inside all aura, potential, promise: every click a crossing over. What exactly is it that’s in the cart? Cyphers for a nameless something. Metaproduct. I often find, after receiving an ordered item, that its aura has dissipated. It’s now an object to be negotiated, fallen from its digital innocence, that ideal commodity state. Items in the cart are, to borrow a phrase from Heidegger, “equally far and equally near.” Suspended in potential. Like Schroedinger’s cat. Not yours, not not yours. Threshold.

Sometimes I will purchase, then cancel, then purchase again, then cancel. Pathological. The cart has its pathos, produces and revises its own logic. It’s like theater. Commerce is war by other means. Is loading the shopping cart like loading a gun? That’s a stretch, but clicking to complete a purchase certainly feels like pulling a trigger. Every order ensures continued suffering somewhere. The cart is a phased-in tentacle of the hyperobject that is global capital—our access point into the communal monstrosity. For every accretion, somewhere there’s a commensurate depletion.

There is copious online data detailing shopping cart abandonment statistics for e-commerce sites. The abandoned cart waits for its Master’s voice to return. How many have you left behind? Oh, what could have been. My Amazon cart with its 605 and counting items is tended like a garden. Pruned, weeded. It’s a kind of hygiene. Could I ever abandon my cart? Leave it unattended, sitting impossibly overfull, bigger on the inside than the outside and ever-shimmering with potential acquisition? And there it would wait, pre-revenant, for some heavily-armed avatar to happen upon it, add it to their arsenal, and descend below the surface of the world to take aim.