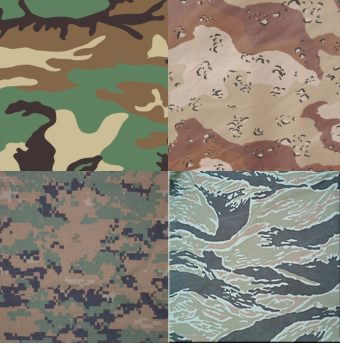

Clockwise from top left: U.S. Woodland, U.S. Chocolate chip, MARPAT Woodland, and U.S. Tigerstripe.

Camouflage was designed to hide things, but how it changed our worldview may be its most revealing surprise. This five-part series examines the history of camo, from its humble origins to its current ubiquity. Catch up with Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V.

PART FOUR: Post-War

By World War II’s end, camouflage tactics encompassed concealment, thwarted perspectives, decoys, and willful misdirection. True to its chameleon spirit, camo was about to assume yet another role: as a visible marker of national identity.

Camouflage patterns began to be printed mechanically onto fabric in World War II, bringing their distinctive varieties into sharper focus. Never just a single pattern, “camouflage” proliferated into a category encompassing literally hundreds of designs. Each country created its own pattern with versions for different landscapes (forest, snow, desert, jungle), then iterated further as war technologies advanced.

Who wore which camo pattern revealed colonial relationships, shifting alliances, and ironic twists of surplus trade. Massive overruns of British DPM (Disruptive Pattern Material) was sold to the Iraqis mid-century, necessitating a redesign in the first Gulf war when Brits and Iraqis faced off in identical gear. A similar fumble put U.S. “frog camouflage” onto French Indochine soldiers, requiring the U.S. to switch to “Tigerstripe” for the Vietnam War.

U.S. patterns keep evolving: M81 Woodland in 1965 became US Woodland in 1981; “Chocolate chip” appeared in 1992 for the first Iraq War, evolving in 2001 to MARPAT, a digitally pixilated pattern.

The Afterlife of Nazi patterns

Nazi-era camo offer a particularly touchy example of how forcefully a pattern’s provenance can resonate. Patterns like Splittermuster (“splinter”), Erbsenmuster (“pea”), Eichenlaubmuster (“oak leaf”) and Platanenmuster (“plane tree”) were altered or discontinued after World War II; clandestine Neo-Nazi markets keep these patterns in active trade. Rather audaciously, the Swiss stuck with Leibermuster, an abstracted Nazi pattern, with only minor revisions until 1993. Arab troops fighting the Israelis in the 1970s pointedly wore Nazi-era patterns until international backlash caused them to rethink their strategy.

But a good camoufleur was always ready to steal an enemy’s design. As U.S. troops invaded Grenada in 1983 wearing Nazi-influenced “Fritz” helmets, a World War II veteran remarked: “I used to shoot at guys who looked like that.”

Clockwise from top left: Nazi-era camo patterns Splittermuster, Platanenmuster and SS Leibermuster. Bottom left is Swiss Leibermuster, used from 1955-1995.

Outside the Theater of War

The Great Wars yielded many pop-culture riffs on camouflage, although few wearable ones. Among the most delicious examples: camo-themed amusement rides, punning newspaper cartoons, board games, even decoy cows. Beauty columnists rushed to apply camo-techniques to one’s appearance, like this 1919 article “Camouflage for Fat Figures and Faulty Faces”. During Prohibition bootleggers sold “cigars” made of glass and discreetly filled with hooch; ladies could opt for “alcoholic opera glasses.” Mid-century cartoonist Al Hirschfeld hid his daughter Nina’s name in nearly every illustration he made. And so on: camouflage infiltrated all five senses and entered the lingua franca, it became a catchall-term for how the world is not always as it seems.

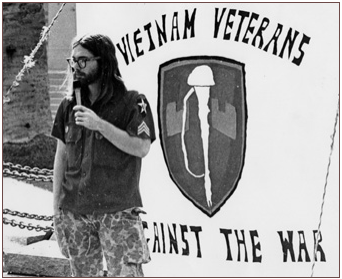

Wearable camo lay dormant in popular culture until the 1960s, when post-colonial revolts, paramilitary movements and sympathetic youth seized on the patterns. It was a military fabric for squares, designed to deceive, as yet unplumbed for visual irony. Worn by once-trim, now shaggy veterans in the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the inversion was beautifully complete: camo now symbolized an aggressive push for peace.

Mark Hartford organizing for Dewey Canyon III in San Bernadino, CA 1971, from Vietnam Veterans Against the War

Jude Stewart writes about design and culture for Slate, the Believer, Fast Company, and Print, among other publications. Her first book ROY G. BIV: An Exceedingly Surprising Book About Coloris now available from Bloomsbury. Follow her on Twitter @joodstew.