To celebrate the upcoming collected stories concert series curated by David Lang at Carnegie Hall (April 22-29), we’ll be posting pieces from past issues of the Believer that tie into with the themes of each show. The third concert in collected stories is (post)folk, featuring Alarm Will Sound, Alan Pierson, and Jennifer Zetland, for which we’re posting Michael A. Elliott’s essay on the Kcymaerxthaere, the fictional universe created by Eames Demetrios (from the November/December 2009 issue of the Believer).

THE GRANDSON OF THE DESIGNERS OF THE MOST FAMOUS PIECE OF MODERN FURNITURE MEMORIALIZES THE SLOW DEATH OF MAIN STREET BY BUILDING AN ALTERNATE UNIVERSE.

DISCUSSED: Non-Native Elvish Speakers, The Kcymaerxthaere, Three-Dimensional Storytelling, The Battle of Some Times, The Limits of the Assembly Line, The Parisian Diaspora, Teri’s Threads, The Conditions of an Ideal Spot for Reverie

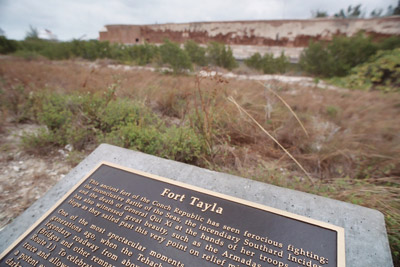

The brick courtyard was adjacent to the railroad tracks on Atlanta’s industrial west side—and part of a structure that had been transformed from its industrial roots to become the home of a five-star restaurant. I must have taken a wrong turn, because instead of finding the bathroom, I ended up staring at a bronze plaque that had been welded into the concrete abutting the building’s electrical boards. It looked just like one of the historical markers scattered throughout the South to mark every scrape and scuffle of the Civil War.

But this one wasn’t like that. “When the Tehachapi incised the Adalanta Desert with the two great sphaltways,” it began, “a settlement at their junction was inevitable.” On this spot, the plaque explained, a woman named Martha Pelaski built her trading post, the location for a series of historic meetings between people with names I didn’t recognize: Nobunaga-gaisen, Iglesia Guitierrez, Síawm Chd. For a second I thought that the local historical society must have been infiltrated by one of those people who prefer to read The Lord of the Rings in Elvish. I looked around to see if this was a joke, and if there was something else nearby that could let me in on it. There wasn’t.

I had stumbled onto the Kcymaerxthaere.

The Kcymaerxthaere is a vast alternate universe created by Eames Demetrios, a California-based artist and filmmaker who began installing the plaques in 2003. The premise of the project is that the Kcymaerxthaere exists as its own parallel world, but its remnants are often visible in our own, “linear” world—intersections that Demetrios endeavors to commemorate by physically marking their presence.

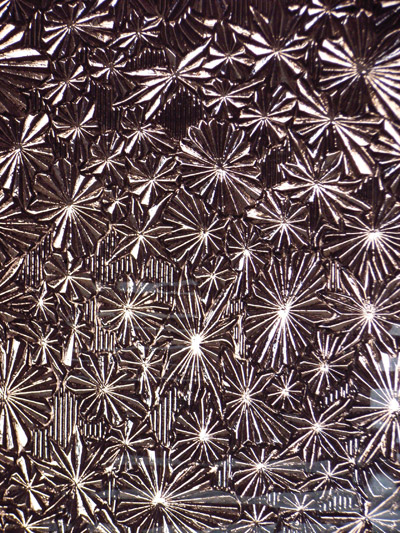

He has already installed over sixty of these faux historical markers, and hopes to increase that number to seventy by the year’s end. Most are in the United States (that is, Kymaerica), while others dot the globe, materializing in Singapore, Spain, Dubai, and Australia. This August, Demetrios even lowered a plaque onto the ocean floor, under forty-five feet of water in the Garvellach Islands of Scotland. In addition to the plaques, there are lectures, websites, travel guides (including Discover Kymaerica), and bus tours. He funds the project through gallery shows that display photographs of the plaque sites, as well as “texture flags”—dense images of physical objects that he says are carried by the people of the Kcymaerxthaere as their national banners. Demetrios calls the project “three-dimensional storytelling,” and says that he hopes to mark some two thousand sites before he is through.

It helps to know a few key features of the Kcymaerxthaere: The world there is divided into gwomes, cultural groups that bear some resemblance to nation-states, though they are much smaller. (There are more than 5,000 gwomes in Kymaerica alone.) The great cultures of the Kcymaerxthaere were made up of road builders, and Kcymaerxthaere history is marked by several massive migrations—across both land and sea. Central figures recur throughout the story, such as the Nobunagas, a father-son legacy of warriors whose saga extends from Korea to Texas (or “pTejas”). There has been warfare, including the enigmatic but crucial Battle of Some Times, and the less significant if more colorful Battle of Devil’s Marbles, where thousands of warriors fought astride giant, vicious war-kangaroos.

At times, it can be difficult to follow. Demetrios calls himself a “Geographer-at-Large,” and he talks about “research” and “discovery” as though he were mapping the Kcymaerxthaere instead of creating it. Each new “find” seems to generate its own energy, so that the stories constantly threaten to splinter and splay in dozens of new directions. When I reach Demetrios on the phone, he is in Basel, Switzerland, preparing to install plaques in Poland and excited about a future installation in Berlin. “What’s great about the project now is that things happen in certain places. So if I get permission to do a plaque in linear Berlin, then it must tell the story of the Bravenleavanne, because they were the ones who built the Monastery District there.”

“Of course it must,” I say, and Demetrios fills me in on the Bravenleavanne, a cultural group with an intense belief in doing good deeds for their own sake.

“At one point, they were in what we would call linear Norwich, England, but then they became so pleased with themselves that people knew about them, and they realized that they had to fade away from that place. Then they tried again in Berlin, but it didn’t work there, either. And then finally they kind of atomized entirely into the hearts of the inhabitants.”

Demetrios, I gather, talks like this a lot, and there’s a certain pleasure in just letting the strange names and events wash over you. He has compared the project to writing a novel and leaving every page in a different location, but I don’t think that’s the right metaphor. A novel is something that will finally hold together in its binding—that can be mass-produced in neat, identical copies as it rolls off the printing press. Demetrios comes from a famous family of mass producers, but also a family that knows we all sometimes require more than an assembly line can provide.

Eames Demetrios, texture flag from Kcymaerxthaere. Courtesy of the artist.

2.

Eames Demetrios is the namesake of his grandparents, Charles and Ray Eames, icons of twentieth-century design who are best known today for their contributions to modern furniture—sleek, single-shell seats of molded plywood, and the padded Eames Lounge Chair. From airport lounges to living rooms, the Eameses did nothing less than remake the world that we see and sit upon everyday. But the Eameses also experimented in cinema, and as I talk to Demetrios about the Kcymaerxthaere, I keep thinking about Powers of Ten, undoubtedly the most widely viewed of his grandparents’ hundred-odd short films.

The film begins with the camera hovering above a man who peacefully naps in a Chicago park. Science books, a perfectly turned picnic lunch, and an appropriately attractive mate surround his resting body. The camera then pulls back, increasing its distance from the man by a factor of ten every ten seconds, moving from one meter to ten meters to one hundred meters, and so on. The earth appears in its fullness, planets spin by, and eventually we retreat to the edges of the known world. Then the camera moves in the opposite direction, burrowing into the man’s hand, focusing on smaller and smaller distances—skin, cells, DNA, until it arrives at electron clouds that buzz in a subatomic frenzy. The film is a kind of “You Are Here” for the cosmos.

Historical markers, at least the traditional kind, aim to locate us in much the same way by yoking a small piece of the earth to sweeping currents of time that we can’t see. This is why the plaques that Demetrios installs are both so disorienting and so effective. No matter how improbable and outlandish the stories they tell, there’s nothing in front of our eyes to contradict them. Like The Powers of Ten, they tell us how much of the universe we have to take on faith.

3.

Paris, Illinois, seems like an unusual place to find out how much confidence the Kcymaerxthaere can inspire. With a population of roughly nine thousand, the town is bounded by fairgrounds on one end and a Walmart on the other. Its center is a town square that seems to be as much museum piece as anything else. An ornate octagonal courthouse of stone, topped by a bell tower reaching 150 feet into the sky, sits on a plot of grass dotted with war memorials. The chain stores have abandoned Main Street, and what remains are local concerns that barely occupy the expanses of their plate-glass windows.

Paris also happens to be the location of Embassy Row, one of a handful of “historical sites” that Demetrios has commemorated with a more elaborate installation than the usual bronze marker. The story is this: In the Kcymaerxthaere, this town was the center of the Parisian Diaspora, a web of communities throughout Kymaerica that took the name Paris (and variations, includingParris, New Paris, and so on)—names that we still use in the linear world. Sixteen members of this Fraternitee des tous les Paris had offices in Embassy Row. Unfortunately, the entire town was nearly destroyed in a five-day riot sparked by political rivalry.

One of the few structures still standing, ironically, was Embassy Row itself. In our linear world, Embassy Row is housed on the second floor of a former Woolworth’s building facing the county courthouse. Completed three years ago, the installation covers 5,000 square feet—seventeen rooms in all. Some rooms still wear the peeling paint and plaster that comes from decades of neglect; others have been painted in the bright colors of the embassy’s gwome. Volcanic rock is strewn about the wooden floors in careful patterns, and broken windows signal the riot’s devastation.

Each room is carefully interpreted through a series of museum-quality signs, complete with maps, diagrams, and photographs. You can learn about the history of the Parisian Diaspora and its remarkable leader, Amory Frontage; you can read about the various districts (from kNue Llorck to Centucky) that sent ambassadors to Embassy Row; and you can see firsthand where the dispute over certification first erupted into violence. At the conclusion, a glass display case holds artifacts collected from the Parises of our linear world—everything from the insignia of the New Paris, Wisconsin, fire department to the nameplates for “Parris Valley Campers” made in Perris, California. The site mimics the idiom of historic preservation so perfectly that I kept expecting to see a Park Service ranger coming through with a tour.

But I was the only visitor on a summer day—judging by the guest book, Embassy Row doesn’t get many visitors—and the midday light entered at odd angles, filtered by glass that had endured since the turn of the century. The air was stale and dusty, even quieter than the placid town square across the street. After a few moments of walking and skimming with the same mid-level attention I give to battlefields and the homes of great men everywhere, I stopped in the middle of the hallway and felt an odd sensation of, well, plausibility.

I must have driven through dozens, maybe hundreds, of towns like Paris, and passed by thousands of buildings like this one without ever venturing into their upper reaches. At some point in history, real history, these spaces must have throbbed with the heat and energy of bodies at work—clerks, managers, secretaries. Yet now, in an age when Walmart has drained town squares of their vitality, that past seems just as strange to comprehend as the possibility that these offices once served as the meeting spaces for the ambassadors of an intricate political empire.

The store beneath Embassy Row still bustles. Teri’s Threads sells uniforms, silkscreened T-shirts, and other customized clothing. The proprietor, Teri Dennis, explains that she met Demetrios through a member of her family, and soon found herself offering him the second floor of the building, which she owns. A graying, sturdy woman who is quick to laugh, Dennis explained to me that at first she didn’t know what to think about the stories of the Kcymaerxthaere that Demetrios was telling. Now, each fall, she helps to organize a Kymaerica spelling bee during the town’s Honeybee Festival.

As she tells me about Paris, Dennis nods to the patrons entering her store. Like the others who have been involved in setting up and maintaining Embassy Row, Dennis marvels at the passion behind the project. The only trouble comes, she finds, when people want the story of Embassy Row to mesh neatly with the history that they already know. “You can’t fit it into a box,” she says. “You just have to have fun with it.” I soon realize that Dennis understands the Kcymaerxthaere better than I do, and I’m grateful when she offers to make me my very own PARIS, KYMAERICA T-shirt, complete with a toppling Eiffel Tower.

When she’s done, I leave her shop to drive out of Paris and into the countryside, until I reach a dirt road marked as DURKEE’S FERRY TRACE—the first road in Edgar County, according to a green roadside marker. After another half-mile, I pull over at a small walnut orchard to read one of Demetrios’s plaques, which of course tells me something different. This is one of historic migration routes of the Parisian Diaspora, it says, and one of the few remaining examples of the early roads of Kymaerica known as Faerie Traces—faerie being a term that means both “lightness” and “intuition.”

The plaque is nestled near a barbed-wire fence and the edge of a cornfield, and the summer has advanced enough that the green stalks reach above my head. The shade of the walnut trees makes this corner of farmland an ideal spot for reverie, and I begin to wish that I could name the roadside flowers that I see growing. Slowly, I kneel to brush away the grass from the raised letters of metal writing. The bronze is warm to the touch, and I pick up the scent of things growing deep into the earth. I don’t know how long I am there before the quiet slowly gives way to the crunching gravel of an approaching truck, and a friendly voice asking me if I need any help in finding my way. No, I say. I know exactly where I am.