On a rainy Saturday in September, I took a MetroNorth train from Manhattan to Westport, Connecticut, to visit Erica Jong in her weekend home. It’s tucked away in the woods down a serpentine driveway, just as I expected. This is the house that I’d read about in some of her novels—well, not this house exactly, but the house of her fictional doppelganger Isadora Wing, a novelist herself, who also writes provocative books in an attic study painted with purple walls, just like Jong.

Isadora first showed up in the infamous Fear of Flying, which made Jong, then a poet and academic, a household name in 1973. The wife of a Chinese-American Freudian psychoanalyst (like Jong at the time), Isadora takes off across Europe with a Laingian analyst named Adrian Goodlove, haplessly and hilariously pursuing truth through sexual freedom. (Her story continues in Jong’s How to Save Your Own Life and Parachutes and Kisses.) Fear of Flying turns 40 this October, and will be re-released in three new editions. It has sold over 20 million copies, and has never gone out of print.

I’ve been a fan of Jong’s since late high school. Discovering her work and her fiery, unapologetically sexual characters felt like finding a sex-positive fairy godmother in print. I had pages and pages of questions, and an hour to ask them. We spoke in her purple attic study. —Whitney Joiner

I. HOSTILE REVIEWS FROM LITTLE BOY WRITERS

THE BELIEVER: I read that you told Mademoiselle in the late 70s that you were one of the most interviewed people in the world.

ERICA JONG: Yes.

BLVR: Fear of Flying had come out, it was a monumental bestseller, and you were on the circuit. I thought about my list of questions and I thought, What more does she have to say? But Fear of Flying came out 40 years ago; so many readers have come to it since then, and weren’t around for what must’ve been such a heady time.

EJ: Heady and terrifying. Terrifying because you have no idea what fame in America is like; it’s horrible. If I go to Germany or Italy, people say “la maestra,” and I’m thought of as an artist. Here, sometimes I look at Lena Dunham and I think, poor girl. She must be going through hell. People in America—if you are a woman and you talk about sex, well, women line up at your door and want to move in with you and leave their husbands, and men all want to fuck you. And they think you’re available. And it never occurs to them that this is writing. America has such hatred of the artist. And it’s not true in other places.

BLVR: Do you think what you experienced then could even be possible now?

EJ: What do you mean?

BLVR: For a book to get that notorious—

EJ: I saw it happen to Naomi Wolf. I took her under my wing because I felt so bad for her. We were on a panel once—Katie Roiphe, Naomi and I. And Katie and Naomi went at each other. This was in London. Katie was attacking Naomi, and I just felt so bad for Naomi that we invited her out for dinner afterwards. I tried to help her because I could see she was coming apart. It’s so cruel. And the Murdoch guy’s papers, in London and New York, are mean. Really mean. And they’re mean to actors, they’re mean to writers, they have no respect for the artist. None. They want to dig up dirt and often they’ll dig up stuff that isn’t even true.

BLVR: I was thinking more in terms of the media vying for everyone’s attention today, and how meteoric the book’s rise was then.

EJ: The media landscape was different. At that time, ’73, writers like Philip Roth and Nabokov would not go on television. They thought it was really low. They refused. And they could get away with it. Gore Vidal, John Updike and Nabokov were on the bestseller list. Now they wouldn’t be. Gore went on television; he was very witty and very funny. But the others would not. They would not sink to television. Now nobody would turn down TV. The reason I did it, despite the fact that I was a Ph.D. candidate in 18th Century Literature at Columbia and intellectual—I did it in self-defense. Because my book had been so distorted, in the way people talked about it, that I had to defend myself. That’s why I did it. I mean, the early reviews were hideous.

BLVR: The New York Times review—

EJ: Was horrible. Lehmann-Haupt reviewed me with Jane Howard’s A Different Woman in the daily review. He said, “I have never been so able to relate to a woman character.” But in the Sunday Review, they picked a guy who had come on to me and been rejected. Maybe the editor didn’t know that. But he wanted to review the book. He said, “Another whiny feminist novel. The heroine doesn’t change at all in the course of the book.” There were many hostile reviews from the little boy writers who couldn’t stand the competition of women writing. So the reason I did TV was to show people I wasn’t a freak, because they had depicted me as this horrible, horrible woman who was flashing her vagina everywhere. And you couldn’t even say “vagina” in those days. Thanks to Eve Ensler, we can say “vagina.”

II. THE UNIVERSAL HONEYPOT

EJ: You know, I did the Vagina Monologues for three weeks at the Westside Arts. I came to understand what a stage actor’s life is like. The car would pick me up at 5:30, our curtain would be at 8:00. I’d go to the theater. I’d be backstage with my fellow actors. We’d hang out. The ritual was amazing. I’m so glad I had that experience, because the heroine of the novel I’m just finishing is an actress. Vanessa. She’s worked as an actress her whole life. She’s done Broadway. She’s done soaps. She’s gone to Hollywood. She’s been in movies. She’s done everything. I couldn’t have really written a character who was an actress if I hadn’t had that experience. And I have many friends in the business. So I sort of know how it feels from the inside. I wouldn’t want to write about a profession I didn’t feel from the inside. But Vanessa is an actor and a writer and she’s a character. She’s really a phenomenal character.

BLVR: I was planning to ask what you’re working on now.

EJ: It’s called Happily Married Woman or Fear of Dying and my heroine is in her 60s. She’s sort of stopped working because, one, she’s married a very rich man who’s much older. And two, she can’t get the parts she wants to play. She doesn’t want to play somebody’s great-grandmother. She’s in a situation where everybody around her is dying. Her husband nearly dies. Her father is dying. Her mother dies at 101, as my mother did. Her beloved dog dies. Her friends are getting cancer and death is surrounding her. She decides that she’s got to find an antidote for death. So she puts an ad on the internet, “Happily married woman with extra erotic energy desires happily married man for one afternoon a week.” And that’s supposed to be the antidote to death. Anyway, what happens is quite funny. The men she meets—one is more insane than the next. And their sexual preferences are bizarre: one man appears in the hotel room holding a rubber suit. Anyway, it’s really funny. It’s all about death, and it’s hilarious.

BLVR: You’ve said for a while that you’ve been working on a novel about Isadora as a “woman of a certain age. “

EJ: I couldn’t do it.

BLVR: You couldn’t do it?

EJ: I couldn’t go back to Isadora. Isadora was the product of another Erica. Isadora appears in the novel as a friend, but she’s not the main character. For the longest time I tried to write a novel about Isadora, and I’m done with Isadora. I’ve evolved as a person. The book wouldn’t gel with Isadora as the heroine. So I put her in in many ways, she has lunch with the heroine; they have certain things they’re doing together. They’re both into stopping time and becoming young again.

BLVR: So that project is—

EJ: It’s horrible getting older, I have to tell you. I mean, it’s wonderful because you see the circles of life get completed, you know. But it’s horrible losing your looks. Horrible. If you’ve been a pretty woman and always pursued by lovers, losing that and not having that—it feels like a great loss. My mentor used to say, “Erica, you’re the universal honeypot; everybody digs you.” And it’s true that I seem to—I’m not classically pretty; I’ve always been too heavy; I’ve had thyroid disease and it’s very hard for me to lose weight—but I’ve always had men pursue me. I’ve always had that ‘it’ thing. God knows why. Maybe it’s pheromones, I don’t know.

BLVR: Confidence?

EJ: I don’t know what it is. Francine Gray once said to me—we were on a plane together going to give a lecture somewhere—she said, “I hate losing my looks.” It feels like your womanliness is gone. But there’s another part of getting older that’s just wonderful. Which is you see the way the stories turn out with peoples’ lives, you know. Like I have friends who were straight, then they became gay, then they became straight again. And you see the way their lives go and it’s just amazing. And you don’t see the way it all works out until you see the whole thing. You become this wise woman. You become this crone.

BLVR: I’ve always joked about looking forward to my crone years.

EJ: You see stuff you never thought you’d see. You see the children of people you grew up with and how the children work out. And I am a passionate grandmother. I mean, my granddaughter, Beth, she’s phenomenal. Molly [Jong’s daughter] and I took her to London because she wanted to see where Queen Elizabeth I grew up and she, Beth, will say, “She never got married and she was the greatest queen England ever had.” We do these girl power trips where we take her without her brothers.

BLVR: I first read most of your books when I was 17, 18, and 19, and they introduced me to a certain kind of adult feminine sexual world. I felt like, Oh, so this is what grown-up womanhood is going to be like!

EJ: [laughs]

BLVR: You know, a lot of lovers, with a focus on your work, your friends, your spirituality. And there was a very clear message that women are sexiest between, say, 30 and 45, or more.

EJ: 30 and 70, for God’s sake. It doesn’t end. The sexuality doesn’t end. It really doesn’t. You’re sexual your whole life, if you’re a sexual person. Sexuality may change, in the sense that men may not have erections. But it’s phenomenal as you get older. And men are better lovers when they’re not obsessed with the “old in-out,” as Anthony Burgess called it.

III. VISIONS OF WOMEN

BLVR: I find it refreshing how healthy a body image your characters seem to have, and how unconcerned they are with age. For women who are wrestling with their sex and love lives, they never seem to care about their weight or express any anxiety about being 39 and single—they’re sleeping with 25 year olds. It feels very different from what we see reflected around us today, where we’re getting married later, but it still feels like there’s so much panic around trying to lock everything down by a certain age. And there’s so much you feel like you have to do as a woman, all the SoulCycling and juice cleansing.

EJ: You have to enjoy being a woman. Why should being a woman be such a negative thing where you always have to improve yourself? I mean, I have never in my entire life met a man who didn’t want to go to bed with me because I was too fat. Never. I mean, never. Maybe they didn’t like my personality, maybe we didn’t click. What is this hatred of the body? You’re not allowed to be a body? You know, we have breasts, we have hips. What is it? I think it’s that we have to get thinner and thinner because we have to atone for being the second sex. What is it? You know, in a way women are fleshier because of estrogen. It’s hard for us to lose weight because when we get super skinny we don’t ovulate. Women in camps during the Holocaust didn’t menstruate and didn’t ovulate. They were starving; they were terrified. Why emulate that condition? It’s nonsensical to me. But it’s also self-hatred, I think. If you look at Girls, let’s say…

BLVR: Do you watch Girls?

EJ: I do, I haven’t watched it all. But I think Lena Dunham is very honest. And look at her women: Are they reaching orgasm? They‘re watching men masturbate. Are they satisfied sexually? No. They’re getting men off, and it’s a good way to manipulate men, of course, giving them blowjobs. Sure, haven’t we all done that? We have. But they’re not having orgasms.

BLVR: I wanted to ask you about Lena Dunham—

EJ: It’s a very dark vision of women, isn’t it? I think she’s good. I’m not saying she’s not good. I believe that writers should be honest, and I think Girls is honest. I’m happy for her. I really feel great empathy for her, going through this instant fame thing, because it’s tough. It is not easy. And then she got a book deal, a multi-million dollar book deal, and everybody dumped on her on the Internet. That’s not fun to go through.

BLVR: But people love her. She’s not been totally dumped on. It seems verboten to say anything negative about Lena Dunham.

EJ: She’s celebrated and also attacked. But the depiction of women is sad, really. It’s a dark vision.

BLVR: Do you feel like there’s anyone out there right now who’s carrying your torch, or any younger female writers or thinkers that you relate to?

EJ: I don’t necessarily read everything. I read what I need to read to inspire the book I’m trying to finish. I’ve seen a lot of things I liked in Jennifer Weiner. She seems to have a lustiness.

IV. OBSESSIVE MOTHERHOOD

EJ: The novel and memoir have fused, as Henry Miller predicted and Thoreau predicted. And the genres have melded, in many ways. I don’t think genre is so important any more. I don’t think it ever was. Even if you go back to Dafoe, he claims that those are true stories. He says, Robinson Crusoe— this is a true story. And if you look at Gulliver’s Travels. Swift is really saying, “This happened to me.” The novel has always pretended to be reality, pretended to be a memoir. If the English novel began in the 18th century— Pamela, Clarissa, Dafoe—I mean, all of these people were the inventors of the English novel. And they claimed they were writing about reality.

BLVR: I wanted to ask about Fanny. [Jong’s lesser-known and widely acclaimed picaresque novel was called Fanny: Being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones.] You’ve said that Fanny is your favorite novel. I read it recently for the first time and was blown away. One of the aspects that made it so enjoyable is that in your novels and your memoirs, we hear a lot about your scholarly and academic past studying 18th century literature, and in Fanny we get to see that put into play, since it’s written in the style of an English picaresque. Is it still your favorite?

EJ: It has been for a long time. I think I earned my chops as a novelist writing Fanny. I feel most connected with the one I’m finishing right now. You always do. But one of the things I love about Fanny is some of the stuff it says about mothers and daughters. I had my daughter Molly in the middle of writing it. She had bright red hair when she was born, and I had imagined Fanny as a redhead.

BLVR: On the topic of motherhood: most of your characters are mothers, but they’re not obsessed with motherhood.

EJ: I adore my daughter and my grandchildren, but I think you’re a better mother if you don’t fucking hover so much. Let the kids have a little space to become who they are. I think this idea that there are mothers today who will follow their kid to school and do their homework for them…Is that good for kids? I mean, where is there space to become themselves? I’m the middle daughter of three. I got the most neglect of anybody. My older sister was drama queen. My younger sister always had meltdowns. And I was left alone. My parents used to say, oh, “Erica’s fine. She gets A’s in school.” I actually think leaving your children alone to fantasize, to write, to make projects on their own is good for them. Breathing down their necks is a form of control. Children should have their own space.

IV. HELEN GURLEY BROWN

BLVR: Around the time that Fear of Flying came out, it seems that there was a lot of comparison between you and Helen Gurley Brown. Did you feel an affinity with her worldview at all, or was that a different—

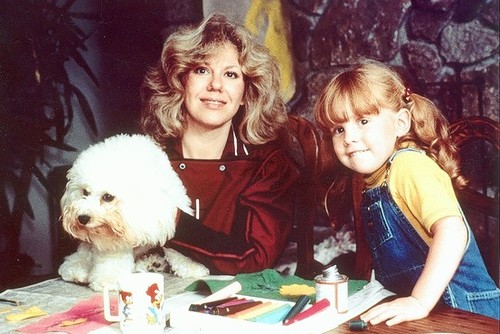

EJ: Helen was so much older than me! She was very sweet to me and she published my poetry and excerpts from my novels. I thought Helen was sort of a joke. But you have to admit that she did a lot of good things for the culture. She took over Cosmo. It was a dying magazine and she made it a huge newsstand success in the days when you could sell a lot on a newsstand. I mean, I think the magazine became silly after a while. But when Sex and the Single Girl came out, which is about ten years before Fear of Flying, is that right? A book that said you could be single and have a good sex life was really a novelty. And she was very sweet about my work. There’s a picture of us together that’s hilarious. Let me show you this. Oh, here it is. This is something. This is Ken [Jong’s husband] when we first got together. Helen said one thing that has always stayed with me, in one of the interviews of books or something. She said, “When you have dinner with your husband, talk with him like he’s a date. Don’t just sit there and stare at each other.” And whenever I have dinner with Ken, I think about it and I think, “We’re having dinner together! We should talk!” I hate it when I see old married couples just sitting there. As long as you’re with someone, have fun.

V. LIFE FORCES

BLVR: I’ve read that your favorite time of day to write is the early morning.

EJ: I prefer to work in the morning. I get up now at five in the morning. I prefer to write early, because by the end of the day I’m exhausted. Five to 12:00. In the morning is when I feel freshest. But when I’m at the end of a novel I often go back to it at night after dinner. And that’s another reason not to drink, because if you drink, you just fall apart after dinner.

BLVR: How would you define your spirituality? In some of your work there’s some Buddhist language and ideas; around the time of Fanny there’s some New Age/goddess language.

EJ: I got very interested in the fact that all the religions that exist today stem from early religions that had Ishtar and Inanna and goddess worship. When I’m in Italy, if I go into a church, I always kneel before Mary—Maria—our virgin mother. And of course she’s a descendant of Ishtar. And Inanna and Diana.

I don’t believe there’s a deity who’s a person. I believe that there’s a force of life in the universe, and that when we’re writing or making music or painting, we’re likely to connect with that flow. I think of it more like Dylan Thomas—the Force That Through the Green Fuse Feed the Flower. I believe certain people can connect with the life force and others cannot. And those people are artists or spiritual leaders or whatever. There is a force of life and we do connect with it. Something weird happens when you write and you’re in the zone—you do know past, present, or future.

Writing a redheaded heroine and then having a redheaded baby…I don’t know how those things happen. But it’s because you go into a zone where time doesn’t exist. I’m sure of it. We’re not always in that zone, but occasionally we go into that zone and often it’s when the writing is flowing. So I believe there’s a force for life, and I believe that in a meditative state you can connect with that. I also believe that in the tantric state you can connect with it with your partner. I mostly hate organized religion, which I think is a force for the oppression of women and creates warfare.

I mean, when I see what the Orthodox Muslims do to each other—the Sunnis hate the Shiites, hate the Druses, hate the Alawites, and they want to kill each other. Orthodox Jews think I’m not a Jew, which is crazy. I have enormous pride in the survival of the Jewish people, the cultural heritage of the Jewish people, but I’m not observant, and I don’t belong to a synagogue. I don’t go to temple on high holy days, but I’m proud to be Jewish. I think the Jews are an amazing group of people and their survival is amazing.

But I don’t believe in organized religion. I believe that people should try to connect with their own life force and let it lead them to do with their lives what they will find satisfying. It’s important to know what you’re going to spend your life on, and the only way you’re going to find that is by connecting with that force inside yourself.