“There’s been a trend recently of trying to quantify how much more empathetic fiction makes us. I think those studies can be interesting, but I question this need to justify reading by quantifying its value or usefulness. At the same time, I do think that there is something to creating spaces where you can dwell in moral ambiguity.”

Four Artworks at the Metropolitan Museum of Art That Jessi Jezewska Stevens Agreed to Talk About with the Interviewer but Ultimately, and for No Particular Reason, Excepting the Picasso, Did Not:

The Actor, by Pablo Picasso

Mada Primavesi, by Gustav Klimt

Cleopatra’s Needle

PixCell-Deer#2, by Kohei Nawa

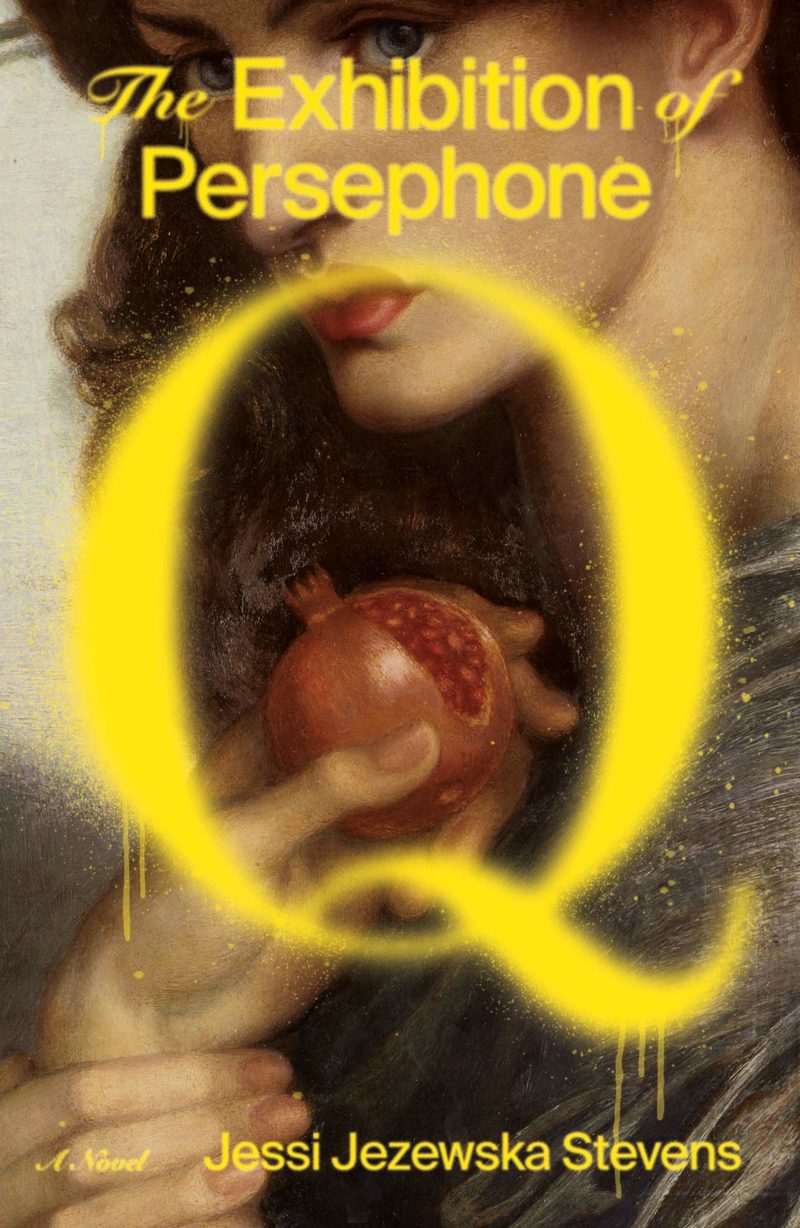

Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s debut novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q, follows the interiority of Percy Q, an insomniac who is haunted by a mystery which I will not try to explain here as I’ve already typed out and deleted numerous sentences that do not do justice to the novel’s central conceit. What I will say: The Exhibition of Persephone Q is an intimate and obsessive exploration of the act of seeing and the act of being seen. It’s also a metaphysical detective story, an investigation of absence and voids, and a darkly comedic treatise on the art world and living in a series of apartments and rooms in New York. Somehow, like a magic trick, a novella is tucked into the last third of the novel. The Exhibition of Persephone Q mostly reminded me of taking a walk at night alongside a brilliant companion who has a keen mind, and an eye for absurdity.

At the Met, I sat on a bench in front of the coat check room. As it turns out, I sat there for fifteen minutes because I did not know what Stevens looked like. Stevens texted me she had brown hair and was wearing a sweater. I looked around and saw many people with brown hair wearing sweaters. Hordes of them, in fact. I simply did not know who she could be! Once we found each other we talked about art, intimacy, and moral ambiguity.

—Patty Yumi Cottrell

I. Favorites

THE BELIEVER: Hey Jessi! [Laughter]

JESSI STEVENS: Hey! [Laughter] Glad we found each other.

BLVR: So, you chose this painting The Actor by Picasso. What do you want to tell me about it?

JS: I’m always a little bit suspicious of my answers to questions about favorites because I think I’m always changing my mind, but this is a painting that I’ve been drawn to for a little while. I can never quite tell if it’s tortured or elegant, public or private. Obviously the audience is implied. The actor seems to be giving this soliloquy, but it also seems like a private moment, as if no one showed up at the theater or something. I guess that makes me think a little bit about writing, which feels both public and private, and also about striking a stance or having a persona. I think of writing very much as, What kind of persona are you performing? And so does your audience, maybe, at least with fiction.

BLVR: So would you say the persona changes with each thing that you write?

JS: I think it can change. I think maybe the best example, or one of the reasons I think about it, is that I notice there are times when I really can’t strike a persona. I’ve never been able to keep a diary, for example. I cannot. I just can’t do it. I have no idea what sort of persona I’m trying to kind of strike… for, I suppose, my future self, as an audience? [Laughter] It feels awkward.

BLVR: Do you decide on the persona first, before you write, or does it come about from the writing?

JS: I think it comes about from the writing. Sometimes when you’re working on something, you begin to realize, “Oh, this feels false.” And then you begin to feel embarrassed. [Laughter] You realize that you’re off-key in some way.

BLVR: But I think that that happens a lot in the beginning anyway? And then it’s a matter of pushing past that discomfort.

JS: That’s true.

BLVR: Because I can’t think of anything where I didn’t have that feeling…

JS: Right, yeah. Also true.

BLVR: I could be wrong. [Laughter]

JS: No, I think there’s certainly that balance between, “Oh, I’m out of tune and this is a bit worthless,” and then simply not allowing yourself to give up. I mean, I’m not sure how it is for other authors, but I do think it’s possible that many first novels are the product of just not allowing yourself to give up on something.

BLVR: What do you think about, in this image, these hands that are coming out of this shape near the lower right. Are those hands?

JS: Yeah! It almost seems like he’s cheating on the exam. [Laughter] Someone else is feeding him his lines. I think I’m also into that aspect of the painting.

BLVR: Well tell me, you were mentioning to me before I turned this on, about coming here when you moved to New York City. When was that?

JS: I moved here in 2012, right after I graduated, because I got a job in New York. It was kind of a corporate deal. I was working more in, like, data analysis. Anyway, I was working these very long hours, and I didn’t really know that many people in the city. And so I would come to the Met a lot, because it was free. Also the Brooklyn Museum. I’d wander around there alone quite a lot. I didn’t feel especially well trained—but I guess I don’t feel especially well trained now, I don’t know if anyone does—but in terms of thinking about issues of form and content and problem solving in that way, those ideas felt more accessible, for me, in the visual arts. I guess it sounds antiquated because you hear about French authors going to the Louvre back in the day. [Laughter]

BLVR: I think that Ben Lerner does that a lot, or his narrators do that a lot. They always go to the museum, they’re always alone, and they like to look at art.

JS: So, I was in vogue. [Laughter]

BLVR: Yeah, you’re in fashion don’t worry. I think it’s good to be antiquated a little because this contemporary moment is so awful; it’s good to be not of the time. [Laughter] The experience of reading your novel, it feels hermetically sealed, and I think that’s interesting.

JS: I have gotten that response before and I’m looking forward to seeing what other people have to say. You had mentioned Patricia Highsmith, and she’s someone people have brought up before in relation to my work. I actually just read Edith’s Diary, which I really love, and I was thinking about that comparison because I love how time works in that novel. It’s clocked to Edith time, which is very much not in step with consensus, and neither is her sort of logic. I was definitely interested in exploring the tensions between someone’s very insistent personal version of reality coming up against a consensus reality. I guess that’s captured in Percy’s insistence that she’s the woman in the exhibition photographs, even though no one else believes her. But when I read something like Edith’s Diary, I don’t feel that it’s so hermetically sealed. Certainly there’s a claustrophobia, but then I’m wondering where that hermetic quality could come from in my own work.

BLVR: Maybe perhaps it’s because she’s frequently out in the world at night. I wonder if it has something to do with that.

BLVR: Maybe perhaps it’s because she’s frequently out in the world at night. I wonder if it has something to do with that.

JS: I love that thought. I do believe that the world changes at night and that experiences change at night. I’m actually thinking, I can’t remember the last time I’ve been to the Met when it’s light out. That was actually something that struck me when I first came in. I wonder if it also has to do with my novel being in the first person. Not only does the narrative cleave to Percy’s thoughts and addled logic, but because it’s in the first person, she is the one responsible for keeping the narrative so close in that way.

BLVR: I’m still thinking about what you said about this feeling of falseness. I’m interested in that. When you’re starting out with something and it feels hollow or false. I’m being a little selfish here, because there are things I’ve started where I’ve had that feeling and sometimes I can push past, and it’s fine. Or it just takes a while and you have to keep writing. Then maybe, you’re like, “Oh I’ll cut that opening and here’s where I’ll actually start.” But also, there have been things I’ve abandoned because, like you were saying, it had that feeling and then you just think, “Oh, what’s the point? I’m just going to be acting for the rest of this novel.”

JS: I think when I really abandon things it’s because I’m no longer interested or I’m no longer having fun, you know, writing it. But then problem solving through sections that feel false is also unavoidable, especially in the beginning. I have a terrible time with beginnings. I remember one thing that I kept running into when I was working on the book was that the backstory felt incredibly false. And so with Percy, I just thought, “Well, she won’t have any backstory until this sort of framed novella in the middle!” [Laughter]

At first I thought the problem with her backstory was sort of a formal consideration of, “Oh, is this even interesting? It’s in the past.” But Percy usually isn’t self-aware enough to reflect on the past and dip into memory in that way. Then I realized that that was why it had felt false, in earlier drafts, when she was more historical and in touch with her own past. It didn’t fit with the kind of decisions she was making, the sort of the person she is, in the first part of the book. You know, she pretends she has no personalized story at all.

BLVR: Which is interesting though because in reading the book, it seemed like there was some sort of backward movement when she was remembering her fiance. It was a little risky to have that novella that you were talking about. It seemed risky to have that the end of the book, like, it must come two-thirds of the way or three quarters of the way but I love that. I love how that completely disrupts the mystery in your book. thought that that was risky and cool to stop the narrative and freeze, and she just completely goes into her past. How did that come about?

JS: I had always been interested in writing a mystery novel, but I don’t think I’ve always been interested in solving a mystery novel. [laughter] I think that, I mean, I’m glad that there’s at least one other reader who appreciates that. I’m certain that for many readers, the feeling of working towards solving a mystery and then ultimately not solving it in the way that it seemed it might be solved could be frustrating. I guess I was also always thinking of that framed novella where… well, I thought it was a little amusing that someone would say, ”Just give me five minutes,” and then just go on and on and on. So, I thought there was a bit of a structural joke there. And I guess I also thought of that section as being another play on the “exhibition.” Percy is giving a separate riff on the exhibition at the center of the book by telling her own story. But, yeah, I guess sometimes I think of plot as patterning, too, and as disrupting patterns. How many times can you restart the book?

BLVR: Everything that I’ve read by you has been in first person. What draws you to that?

JS: Recently I’ve only been writing in third, at least in fiction, but at the time, I guess I was very attracted to Percy’s voice and the things that I was reading as well. Oof, I feel a little distracted because my partner always warns me that I’m way too abstract in the way that I talk about writing. [Laughter] And I feel like I’m doing that again. My students tell me that, too.

Anyway, I had mostly been writing short stories before I wrote the novel. When I was writing those stories—and I think short stories should be a little bit like drugs—I was attracted to a kind of frenetic energy. The first person was my way of exploring that.

BLVR: What is it like writing in third?

JS: I’m really enjoying it. I think I’m attracted to it because it opens some interesting territory about what kind of suspension of disbelief you need to have for a novel now. We’re so saturated in fiction all the time, given the dominance of TV and film and social media, that when we meet an omniscient third on the page, how do we deal with that? Like the omniscience of the 19th century novel.

BLVR: Like Balzac.

JS: Yeah, and if you want to use that kind of omniscient third today, how do today’s readers respond to it and how do you navigate the suspicion that this feels tired?

BLVR: How do you keep track of everything that’s going on with that? I think that must be like the greatest challenge of writing because I can’t imagine. I read Cousin Bette recently and I had no idea how to keep track of all these relationships and the tensions between each relationship and how this relationship is adjacent to this one, and then it intersects here, you know? It’s exhausting.

JS: I guess maybe when life was more dominated by formal social codes, as it was for someone in a 19th century novel, [laughter] then maybe it feels more natural to be thinking about all of that? [laughter] I actually recently read Balzac’s The Magic Skin, and there’s a framed novella there, too, so I thought that was interesting. But, yeah, I’ve been thinking more about, if we have an omniscient third, are there different characters or moments in the novel where it almost seems like that consciousness actually has a source in the book, while still feeling sort of detached.

II. The Land of Immortals

BLVR: Okay, so, now we’re sitting on a bench in a wing that is called the Land of Immortals. We were just talking about antiquated fiction. So, what is your favorite antiquated novel? [Laughter]

JS: Gosh, let’s see… again, still suspicious of favorites. Does Zola count as antiquated?

BLVR: Yeah, definitely.

JS: I feel I’ve had a bit of a soft spot for Zola recently. I often find him pretty sentimental. Maybe that’s what feels antiquated about it—that he could get away with that kind of overt sentimentality.

BLVR: I’ve never read him, am I missing out?

JS: I think a lot of people would say that you aren’t, but… I guess something that I read recently was Germinal, which is the story of conditions in a mining town during the French Revolution. It’s super sentimental. Though I do think the French Revolution is feeling more and more applicable to modern times. I’m not sure if I could say the same for sentimentality. But, yeah, what about you?

BLVR: I mean, I like Jane Austen. I think she’s pretty great. I read a lot of older fiction. We were just talking about Robert Walser. I don’t think he’s antiquated but he’s old fashioned I guess in a way, so I’m a big fan of his. There are authors that I think of as bachelors and he’s a bachelor author. He always writes about these chaste bachelors. There’s something cheerful about his writing but also kind of sad. I like Thomas Bernhard. I like W.G. Sebald. I read a lot of dead authors.

JS: Yeah, I also read quite a few dead people, but instead of favorites I maybe think of books most returned to. Do you know what your most read books are?

BLVR: Yeah. [Laughter]

JS: Yeah, I guess now I have to answer! [laughter] Mrs. Dalloway is probably one of my most read books. Probably also Molloy, actually…

BLVR: Oh, nice! I love Molloy.

JS: And maybe also Lolita if I think about it.

BLVR: Yeah I love Lolita.

JS: There are many ways to think about that book, but one way that I like to think about it is as a writer… [interrupted by alarm going off in the gallery] What did I do? [Laughter]

Anyway, as a writer setting himself the challenge of, If I’m to write in purple prose in this way, can I seduce a reader into this kind of story…?

BLVR: Yeah, all of those writers are so purple.

JS: Colors in “Lolita,” if you’re paying attention to the use of color, you know, Quilty especially always has this purple thing going on. So, I kind of like reading it as this terrible celebration of the power of purple prose. I guess that’s sort of an ancient idea, of rhetoric casting a spell in order to persuade people of, or seduce people towards, ideas that, presented in any other mode, you would absolutely reject.

BLVR: I think Susan Choi actually veers on that side sometimes. Sometimes her prose is beautiful, sometimes it’s off-putting. I think she’s brilliant. As I’m reading her there are times where I’m like, “I can’t tell if this is bad.” [Laughter] I love that about her. I love that she’s willing to make it seem kind of bad. That’s why she’s so talented, because she can pull it off. Maybe that’s why her work is so polarizing. I think those are the writers I feel drawn to. I feel drawn to polarizing writers. I’m not interested in ones who are “technically perfect.” I just don’t think it’s interesting.

JS: I think probably one of my favorite living writers today would be Marie NDiaye. Have you heard of her work?

BLVR: I’ve read a little. Did she write Self-Portrait in Green?

JS: She did, yeah.

BLVR: Yes, okay, I’ve read that.

JS: I think that Rosie Carpe might be one of my favorites. We were talking a little bit about Patricia Highsmith, too, but in terms of writers who can create this kind of claustrophobic psychology and something that’s both very beautiful and kind of ugly at the same time, NDiaye is really good at that. But I think in her books, it’s people and the way that they treat each other that can be so ugly. And something else she does well and that’s so unsettling is how her characters never seem to express having fully registered how deeply they have been wronged.

BLVR: The way you’re describing her work is making me think of Fleur Jaeggy. Have you read, Sweet Days of Discipline?

JS: Yeah, which I also love.

BLVR: That one is great. There’s something cruel about her writing—and unapologetic.

JS: Absolutely unapologetic, yeah. I wonder if that’s something that could be a quality of a lot of great writing, to be unapologetic in some sense. Maybe that’s why we often say it takes a lot of arrogance to write. [Laughter] Yeah, I mean, thinking about Jaeggy—and NDiaye—I think in my own book, too, I was interested in cruelty and capacity for violence, especially in characters from whom you wouldn’t usually expect it. I think that is something I’ve been fascinated with for quite a while. Sweet Days of Discipline, of course, is kind of a paradigm of that.

BLVR: I’m curious about how you think about intimacy in your writing between characters, whether physical or emotional or both, whatever… I’m just curious about that, or the lack thereof.

JS: Yeah, I think that intimacy is really important in my work. Maybe this circles back to your earlier question about the first person, too. Having a first person narrator who seems to feel more intimate with the reader than anyone around her is, I think, an interesting situation to explore. I’m especially interested in that denial of intimacy, and I think one way to read The Exhibition of Persephone Q is as the story of someone recognizing the intimacy that already exists in her life, but which she’s neglected or ignored. In terms of building intimacy with the reader, too, a first-person narrator is of course confessing to the reader all the things that she keeps from everyone else. And I think one model that I’ve often had for the first person is of meeting someone alone in a room who seems to be speaking directly to you, yet you feel that even if you closed the book or left that room, they would continue to say the same thing, in exactly the same way.

BLVR: That makes me think of Bernhard. I mean, they’re monologues right?

JS: Absolutely.

BLVR: Do you use quotation marks in your book? I’m sorry, I don’t remember.

JS: I don’t.

BLVR: That’s interesting. I didn’t realize that it was a problem for a lot of people.

JS: I have heard that it’s a problem!

BLVR: I know it’s a problem.

JS: [Laughter]

BLVR: They have their own use.

JS: I know that many editors and readers have a problem with leaving out quotation marks. But if you want to create a voice that seems very insistent on its project of confessing to you a story, and at the same time establish the sense that the speaker is not actually particularly aware of the reader—that the story isn’t necessarily for the reader’s benefit—then not including those grammatical marks mutes the speaker’s awareness of being overheard in this way.

BLVR: I mean, the quotation marks slow it down, too, because every time you see them you’re reminded that someone put the quotation marks there.

JS: Right. In first person, it also marks a transition from interiority to reported speech. And if you have a character who isn’t especially interested in being that convenient for the reader—and, I do think of that as, you know, not just style, but actually part of your first person narrator’s relationship to telling her story—well, then…

BLVR: That’s awful. [Laughter]

JS: I guess. [Laughter]

BLVR: That’s something I do a lot too, where I’m like, “Should I just use them, should I just make this more accessible in a way?” what we’re talking about, it does ask the reader to do a little bit more work because you have to be paying enough attention so you can tell if someone is saying this, is this in their head, did someone actually speak this to another character, are they thinking about saying it?, it asks the reader to do a certain amount of work which I don’t think is a bad thing, but there are times when I feel I might as well use quotation marks because most of my friends do, too, and it’s easier to just do it.

JS: [Laughter] Right, right.

BLVR: It’s okay to use these quotation marks. [Laughter]

JS: Right, I think all writers will admit to that kind of negotiation in some way. Wait, we were just talking about first person voices that would continue to tell the same story even if the reader wasn’t there, and I think Bernhard is a fantastic example. Maybe some first person Dostoevsky, too, like Notes from Underground, which then reminds me of Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison. That’s another most-returned-to book for me. I really love that book. I think it’s a permission book in many ways but, thinking as a writer, one of the things that I especially love about it is the way that Ellison writes about New York. It’s a recognizable city landscape, but there’s also this absurdist element. To be able to write about a city that’s so written about, and so well known, and to take the liberty of placing it into a slightly absurdist register… I love that.

BLVR: You’re making me want to read that again. What about the use of ambiguity in your novel?

JS: I think that’s what fiction was always for, a space for ambiguity. I’m thinking about my own book, and there’s certainly ambiguity at the plot level in terms of, “Is Percy the woman in the pictures, as she claims, or is this simply an obsession and a fantasy of hers?” But I also think that fiction has the capacity to let us dwell in moral ambiguity as well. If we’re listing qualities of books that we really love, having moral ambiguity and possibly a lack of apology are two things that I’m interested in.

BLVR: I’m trying to think, if we’re talking about dwelling, even at the plot level, if we’re thinking about dwelling and not knowing our uncertainty. What do you think can be recovered there? What’s recuperated there by dwelling in that space, whether at the plot level or morality. [Laughter]

JS: I did start writing this book right around the beginning of the 2016 election. Ideas of paranoia surrounding national identity were on my mind, and I while I didn’t set out to write a historical novel, it seemed to me that a period of paranoia and uncertainty about what this nation is, and how we respond to that uncertainty, was certainly bookended, in a way by, 9/11 and the that election cycle. So I chose the post-9/11 backdrop for the book with the intention of setting up a very contemporary sense of uncertainty around identity, and around events that tear through comfortable narratives about who you are and about what, possibly, this nation is. I think being able to be more comfortable, as individuals or as a nation, with uncertainty and ambiguity is maybe a moral imperative. To live with ambiguity rather than try to assert dominant narratives, which in a way is what Percy is trying to do, when she goes on her quest to prove that she’s the woman in the exhibition. She’s trying so desperately to assert this version of the way she sees the world, and herself, over and above every indication that it may not be the truth. On the other hand, why do we have such a hard time believing her? Did I answer that question? [Laughter]

BLVR: Definitely.

JS: I appreciate that question. There’s been a trend recently of trying to quantify how much more empathetic fiction makes us. I think those studies can be interesting, but I question this need to justify reading by quantifying its value or usefulness. At the same time, I do think that there is something to creating spaces where you can dwell in moral ambiguity.