Gender entails an act of translation between interior truth and social performance. Binary gender roles in particular are marked by external and internal assessments of difference, where the constituent elements of boy and girl align like a primary school lesson on antonyms, ignoring the complex dynamics of power, privilege, and personhood that jostle beneath these words’ surfaces. As unsatisfactory as it is, this gender-essentialist system still holds society in its grip, even if at the individual level, what boy and girl mean is far less predictable; personal results may vary. Rebecca Hazelton’s new poetry collection, Gloss, examines the rhetoric of gender roles through poems that distill and subvert essentialist language with concussive force. As the collection probes the invisible but very palpable infrastructure of a gendered status quo, it exposes just how much we want to believe in the safety of gender norms instead of acknowledging the gray zones between social expectation and internal truth, between stricture and structure.

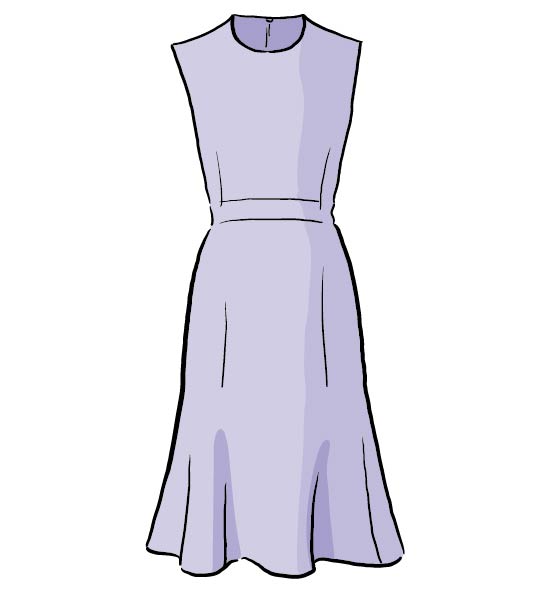

Gloss is divided into three parts—“Adaptations,” “Counterfeits,” and “Self-Portraits”—and at every level, the meanings of the word gloss multiply, blur, and bleed into one another. As Hazelton plays with the relationship between gender roles and the images that perpetuate them, she subverts the stereotypes and dichotomies we unthinkingly accept. Using social expectation as a dark mirror, the poems employ a logic of “both/and” to reconfigure our scripts around gender, so that a larger, more complex composite can emerge. In “Self-Portrait as Thing in the Forest,” the speaker examines a gowned woman whose image functions like a Rorschach test. “Behind this dress, / [are] two women / in the mess of one body hardly covered / by the stiff beauty of lustrous rustle.” Both versions are a gloss of what it means to be a woman, whether the gloss fits or not, and the woman beneath these images is just as susceptible to an interpretative gaze as an inkblot image. Whether the woman is seen as a bride, a femme fatale, or a truth that encompasses both depends not only on who’s looking but on what they’re prepared to see.

Throughout the collection, the poems’ subjects aren’t just passing through the world. They’re also trying to pass through the images that surround them and to traverse the distance between personal understanding and public presentation. Often these forms of passage connect through...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in