I first encountered Emerson’s work while on a search committee at Goddard College. We were looking for a creative nonfiction writer to advise the independent work of our BFA creative writing students. Emerson was getting his PhD from the European Graduate School, had college-level teaching, spent time as a journalist, with work featured in The Huffington Post and the anthology Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics.

Emerson sent a sample of writing from their first book, Ghost Box, which is based on the story of Emily, who arrived in the parking lot of a vacant big store, or “ghost box,” near downtown Los Angeles with 45-pound bags of cat food in the fall of 2012. Emily makes this ghost box into a bird sanctuary and the LAPD can’t catch her. A blend of poetry and prose, I bought the book and Emerson got the job. Now a doctor of philosophy, he continues to teach at Goddard and is a Dana and David Dornsife Teaching Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies at the University of Southern California.

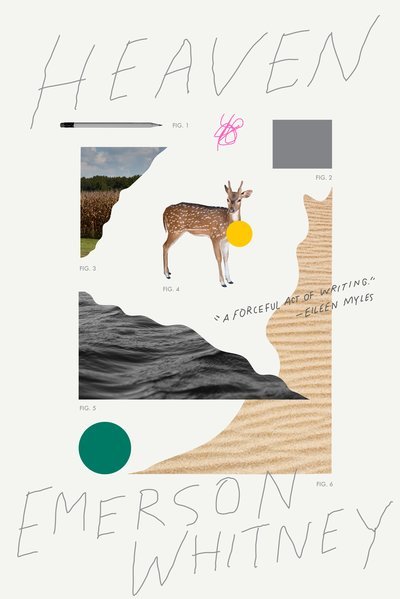

I appreciate the poetic rigor and stamina of Emerson’s lyrical and documentary “I.” The willingness and need to be there, living the story as much as possible. He looks and looks again and this is the tension in the narrative, the ritual that deepens and forms insight. In his forthcoming Heaven, Emerson, through childhood memories and critical texts, is questing through the story of their body in relation to their mother. “I am like Mom,” Emerson writes, “Symmetrical and tan. I write about her body because of my own discomfort, the oil drum fire that is myself.”

—Arisa White

THE BELIEVER: You write such alive sentences; how do you do that? How do you approach the function and purpose of the sentence?

EMERSON WHITNEY: I love making work that vibrates and wakes up in general under somebody’s gaze. Glad it’s doing that for you! I approach the sentence like I hang out with a friend. I’m so happy to be with sentences.

BLVR: Why Heaven as the title for this book, especially with its religious connotations?

EW: In the book, my mom asks if I think she’s going to heaven. I was visiting her recently and she actually said it again, like maybe in heaven you get to do everything you didn’t get to do in your life that you wanted to do. I was surprised to hear her reciting some of the lines in the book almost exactly, but I realized it became a device for me in the text because she does mention...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in