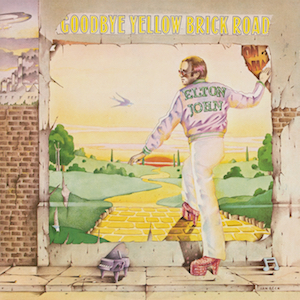

Little by little, I’ve been converting my cassettes to MP3s. I do this in the evenings, when Dave takes over the kids and I get my office back. I have a lot of mixtapes that I want back in my headphones. I’ve digitized the most important ones—those my friends have made for me—and am now trying to decide what to do about the studio tapes I purchased in college. Surely I don’t need a scratchy copy of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road on my computer—it’s on YouTube!

Sheltering in place is making me sentimental, I fear. This conversion project has been on my to-do list for a decade, and suddenly I’ve made the time for it, so now I’m listening to Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and it’s 1999 and I’m on the campus of Rochester Institute of Technology, a former farm that still sounds like a farm at night. I can hear all kinds of insects whose names I don’t know in English or in Russian, because—well, this is a different continent from the one I grew up on, and surely these are different insects. I have no idea. I’m studying business. It’s July, two in the morning, and I’m circling the athletic field with headphones in my ears. It’s hot, but not as steaming as it is in my dorm room without air conditioning. I’m exhausted after a full day of classes and missing my family and friends, but I can’t fall asleep in the heat. None of my old tricks work—not counting sheep, not picturing myself as the heroine in a modern-day version of Cinderella. I’m sort of living my fairy tale already, after all, and it’s way too hot.

I’m about to start my senior year, my fourth year away from St. Petersburg. My college friends have gone home for the summer. I have one phone call a week with my parents and handwritten letters to my aunts. Email is coming slowly to Russia. Dave has just graduated and moved to Texas, without any clue as to where he might land after his three-month job training in IT. I feel so lonely that I’m about to lie down in the unmown grass next to the field just to feel some connection to the earth. I anticipate the coolness of grass on my greasy face. Then the sprinklers turn on. So much for the illusion that this was still a farm.

Instead, I look at the moon and stick to the lined path, making circle after circle, and I sing along to my cassette. My English is pretty good by now, but not when it comes to song lyrics. I understand only some of what Elton John’s saying, and I have little idea what any of it means. I don’t even care. When I can’t figure out what he’s saying, I just make up the missing word, and the result means something to me.

When are you gonna come down?

When are you going to land?

I should have stayed on the [phone]

I should have listened to my [oh my]

I should have listened to my grandmother, I think, who warned me against going away to America. Now every time I talk to my parents I hear news of her decline. She’s taken a bad fall and been confined to her bed; she’s starting to lose her mind to dementia. Returning home isn’t an option—too expensive, too far—and I don’t know how to help her. I feel powerless, my chest unable to hold the heartache I’m feeling. Which is why, when Elton John lands on “Oh I’ve finally decided my future lies / Beyond the yellow brick road,” I yell the words into the night. That place beyond, on the other side of ambition and desire, feels the most desirable.

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road came out in 1973, four years after the Stonewall Riots, a few years before Elton John came out as bisexual. In 1999, though, I still had yet to shed much of my socially conservative Soviet upbringing, to discover even how invasively Soviet censors worked at excising all information about bi- and homosexuality. I thought the album was saying something akin to John Lennon’s “Watching the Wheels”: Elton John was tired of drinking and drugs, ready to give up the rock ’n roll lifestyle. Today I find myself interpreting everything he says as a different code, forged in the lingering heteronormativity of the era.

Listening again now, I think my favorite part of the album must be the instrumental beginning: a creepy sound of wind blowing and chimes ringing, then something that sounds like synthesized funeral music, deep dark notes slowly moving up the scale until they dissolve into “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding.” The narrator gives us just a hint of his dark thoughts before transforming his fears into something else—the pathos of hope and wishful thinking. It’s not a very contemporary move. Today, I imagine, he would let us stay with that dark opening a lot longer, perhaps for the duration of the album. But then we’d miss out on the carnivalesque. He lands, toward the end of the album, on “Harmony,” which despite the platitude of its lyrics—“gee I really love you”— has always been a tragic song to me, one whose meaning is exactly the opposite of what the title says. Possibly because, as a twenty-year old, I heard him saying not “never leaving harmony” but “never live in harmony.”

— Olga Zilberbourg

San Francisco, day 45