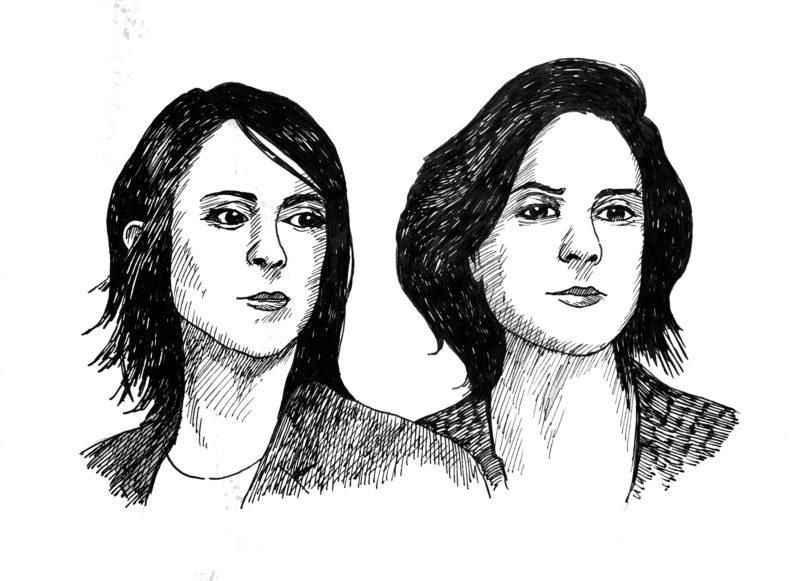

Tegan Quin and Sara Quin are monozygotic twins. I looked it up: it means identical, from a single zygote. One evening at a backyard dinner party, Sara explained to me: “We were supposed to be one person.” She extended her pointer finger between my face and hers. “One person! How fucked-up is that?” They are an indie pop duo: both are singers, songwriters, and multi-instrumentalists. They’re queer, are my hairdo heroes, and have released nine studio albums—most recently Hey, I’m Just Like You, a companion album to their memoir, High School. The album and memoir were both released in September 2019. In High School, they tell their origin story. In alternating chapters, they narrate their sticky teenage years in Canada in the ’90s, when they ate a lot of acid, discovered their homosexuality, fell in love with their best friends, hooked up with those best friends at secret sleepovers, wrote incendiary love notes, wore striped sweaters and wallet chains, discovered the guitar, wrote songs. Sara came out to Mom first; Mom freaked out; Tegan had it easier.

In 1998, Tegan and Sara won Garage Warz, a battle-of-the-bands contest in Calgary; it propelled them into what has now been a two-decade career in the music industry. Their career has traversed sonic terrain—from folk/punk, to indie rock, new wave, and ’80s synth, to modern pop. They are known for their memorable melodies, compelling lyrics, and easy, often hilarious anecdotal banter onstage. Their songs have hit the Billboard Top 40. They’ve gone Gold and Double Platinum, with over a million albums sold. They’ve been remixed, covered, and have collaborated on projects such as 2014’s Academy Award–nominated theme song for TheLEGO Movie, “Everything Is Awesome!!!” They’ve won JUNO Awards and have been nominated for a Grammy and several Polaris Music Prizes. In 2018 they were granted the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award, Canada’s highest honor in the performing arts.

Hey, I’m Just Like You lassos their past to their present. It’s an album of their demos from high school, originally recorded on cassette tapes, which they unearthed when researching their memoir. Staying loyal to and protective of the incipient teenage heartbeats in the tracks, they re-recorded the songs they wrote as kids, zhuzhing them gently with the sensibilities they’ve cultivated in their two decades as professionals. Tegan and Sara developed the album tour into a unique stage show where they read from their memoir; performed stripped-down, acoustic versions of the songs on the record; and projected analog home videos from their high school days. They donated a portion of the tour proceeds to the Tegan and Sara Foundation, the duo’s charity focused on fighting for health as well as economic, social, racial, and gender justice for LGBTQ girls and women. As Tegan puts it, “We’re raising money for girls in our community, arming them with tools to lead and excel.”

They both recently moved from Los Angeles to Vancouver with their partners. I’m a friend of both Tegan and Sara and a fan of their band. When we spoke by phone, we yakked about gay stuff, and I asked them to reflect on their youth, their coming-out stories, how they experienced sharing High School, and the book’s impact on readers over the course of its first publication year. The dominant theme of the book—the experience of being seen (or, more frequently, not seen) by their parents, schoolmates, teachers, and especially each other—struck a chord with me. After writing the book, the sisters were startled to realize just how different their experiences of adolescence were, even while living under the same roof, and even though they share all that DNA.

—Marisa Matarazzo

I. THE STRAIGHTS

THE BELIEVER: High School has been out for going on three quarters of a year now. You’ve toured with it and developed and performed a stage show. Have you been surprised by how your story has landed in the world?

SARA QUIN: I really expected gay people would be the ones who would deeply connect with the material. The truth is, a lot of the really satisfying conversations I’ve had have been with straight people. I think they’ve found so much in common with our story that it’s enlightening to them to be able to have their experiences framed within a queer story. It’s illuminating. Which I find really interesting because so much of what I consume, and what I find interesting and profound, is through a straight person’s experience. I mean, I have to listen to straight people sing and write and talk and act all the time, and I take from these stories what applies to me. And so asking straight people to do the same with our story seems to have such a big impact on them.

TEGAN QUIN: I just couldn’t believe how many people outside of the queer world were identifying with the book, and that felt really exciting. At the beginning, just talking to writers, I was moved by how many straight people related to the book, how many men were like, “Oh my god, like, replace, you with me and this was totally my experience.” I think a lot of guys relate because they also have had crazy, intense crushes on women and felt weird about it. Or they were rejected by their best friend, who happened to be a girl. The pining and internalized rejection really is a teenage boy story, in a weird way.

SQ: My puberty experience was pretty similar to what I read about guys feeling. The summer before grade seven, I don’t remember being more terrified by anything in my life than a girl in a bathing suit. And this was so shocking to me because I had spent my whole life swimming. We were always at the pool. But it was like overnight that girls in bathing suits just completely changed for me. Overnight, at the thought of a girl’s bare arm touching my bare arm, I just was like, I’m gonna kill myself. I can’t deal with this. [Laughs]

I remember thinking, Oh, I’m like a boy. I was fumbling through, trying to find some kind of explanation for myself, and so I had to use the framework of heterosexuality. And I did not ever imagine girls were behaving the way I was behaving or having the thoughts I was having, about girls or guys.

TQ: So many queer women have been like, “Thank you for articulating why we were so obsessed with men.” We wanted to be like them. We wanted women to like us the way they liked Jared Leto. I wanted them to desire me the way they desired him. And I couldn’t have articulated that at that age, so I put him all over my walls because it generated this feeling in me. I wasn’t imagining kissing him; I was imagining being him.

BLVR: On the subject of posters—Sara, you had mentioned your My Girl poster…

SQ: Yeah, I remember I was really obsessed with the My Girl movie poster because I felt weird about Anna Chlumsky. I didn’t know how to explain it. I’d just lay up in my bunk bed at my dad’s house on the weekends and stare at the poster. When I think about it now, I’m like, Yeah, duh. Or, like, Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon in Thelma and Louise. The thought of the two of them… I have this fantasy from when we were kids, where I would imagine being kidnapped by an older woman. An older woman would take me out of school—I knew she was kidnapping me—and nothing would happen sexually. But just the thrill of imagining an older woman kidnapping me was enough to sustain my mind for hours. I think, when I was too young to even really imagine anything more than a scenario in which I was next to a woman, there was desire and fantasy.

BLVR: To go back to the framework of heterosexuality, my experience is that we gays get a fair amount of practice reframing scenarios we’re presented with, which are often hetero. We scan love stories and rearrange them slightly—in a homosexual way. So have any of the straights explained what it was like for them, reading your book?

SQ: “The straights.” [Laughs] As a queer woman, I’ve been forced—due to complete scarcity—to consider life through the artistic lens of people who aren’t like me. I think it has made me a more intelligent, observant person. To have these conversations about our experience with straight people has made me feel more understood and closer to a lot of people.

Although I will say, one thing I was not completely prepared for is that the conversations made people feel really uncomfortable—this happened less with the book and more with our live show that’s based around the book. The conversations caused people to think about difficult things that happened to them. And it’s made me rethink and reframe the trauma of art and performance. There’s something euphoric and sort of freeing about watching an audience really emote when it comes to music, but there is something altogether different about asking people to sit for two hours very quietly without touching their phones and listen to us talk about our bodies and our identity and internalized homophobia and heartbreak.

There was a part of the show where I read from the chapter about the guy in class who’s using the word fag and talking about fags getting AIDS and I recount how I threw a chair when he said that. Sometimes people heckled me. They would laugh or say they didn’t like me using those words in a public space. Sometimes the whole audience would cheer and sometimes they would be deathly quiet. Night to night, I just didn’t know what would happen. I really experienced a great deal of satisfaction from that part of the show, because I don’t want people to forget how homophobic and how difficult and how scary the world is.

There’s this weird irony, but I sometimes felt that the straight people in our audience were more empathetic and more available. I say that only because I think, Why wouldn’t they be? It’s not trauma for them. They’re getting to observe it as outsiders. In a lot of ways, it’s been more complicated to process the book with gay people. But, of course, it’s easy for me to focus on the moments of criticism or conflict—I’ve had people be like, “I don’t want to read your book. I don’t really want to go back to that time, thank you very much.” And I’m like, “What? Why?” I’m sickeningly obsessed with going back to those difficult moments, but maybe that’s my job as an artist.

II. THE UNVEILING

SQ: When I started listening to the music, I realized I had rewritten high school in my mind as this difficult time with crappy music, and that things got better after it. And when I listened to the music we wrote in high school, the original demos, I could really hear joy. Even in between some of the demos, or on video, we’re joking around and laughing. I think there was a grieving process connected to the realization of how fun it was to be a musician before making music became my job. I felt a real sorrow at having to become professional, because I wanted to play music for my friends.

BLVR: The letters, notes, and journals referenced in the memoir are really charged artifacts from the time. There’s so much inclination to write down what you’re going through. And these writings become dangerous because they contain your secrets. They got you both in trouble several times. The notes between Sara and her first secret love: the ones where you describe your sexual fantasies and, Sara, where you specifically describe a fantasy of wanting to be watched by—I think it was your drama teacher. You write, “I wanted a witness,” which I thought was profound. And so revelatory of the theme of being seen. How interesting is that desire to be seen, to be witnessed as a lesbian or having lesbian sex? The desire is so strong, it becomes erotic. Writing these notes—producing proof that you are hooking up—and then wanting eyeballs on a private fantasy: it’s so rich and conflicted and exciting.

SQ: I don’t even know why the details eventually didn’t make it in there, but the drama teacher was young and he was obviously gay. So there’s that. I didn’t imagine a heterosexual man watching us. I actually don’t think I imagined him watching us and getting turned on. I was excited by the idea of being seen as a queer person by another queer person.

BLVR: Oh, that’s really fascinating. What was it like to recognize that you each had very different experiences of coming to understand your identities during your adolescence?

TQ: You know, family and friends have made me feel really seen, in that Sara and I are telling two very different stories. We experienced our adolescence and our identities and coming out and the development of our sexuality and even ourselves as musicians almost in isolation. You can tell that to people, but they still see us as a unit. And they’re well-meaning people who don’t even realize they’re doing it. I think that releasing the book has allowed us to have lots of those conversations.

I think I did have a very different experience from Sara’s. And that’s affected my whole life. I don’t really feel internalized homophobia or uncomfortable about my sexuality in the way that Sara does, and I’m glad she got to tell that story, because I think a lot of people feel the way she does. We’ve been overwhelmed by the number of people who’ve come up to us over the last couple of months to say how wonderful it was to see us share the part of our story when we struggled because we were closeted, and when we labored over how to come out. A big part of what happens when you become a public figure is that you’re supposed to tell this really positive, awesome story: “Look, we’ve been embraced and loved and we’re popular, so it’s OK to be gay!” There’s just so much pressure on public people to tell only the positive side, and so I’m glad Sara told that part of the story. But it was super important to tell my part, because I also feel like the only time we ever hear about queer stories and coming out, it is negative, and I was like, “OK, but mine wasn’t. Mine was kind of awesome.”

BLVR: There’s a spotlight on the moment when you both cut your hair. Tegan, you write, “I’d been hiding for a long time. But now I wanted to be seen.” And “As she cut, the me I had imagined finally materialized.” And Sara writes: “I was convinced that Zoe would reconsider her rejection if she saw me looking so much like myself.” Hair can be a signifier of a person’s nontraditional, non-hetero relationship to the world. You guys are famous for your haircuts. I’ve googled “Tegan and Sara hairdos” because they’re fabulous. And I’m always like, Maybe I need that one.

TQ: Prior to writing the book, people often asked, in the context of our career or in terms of coming out, “If you could talk to your younger selves, what would you tell them?” And the first thing I always said was “Cut your hair.” And now, having written the book, I think I would never say that. As an adult, it seems so judgmental of me. Sara articulated this idea very well over the last couple of months. We were bullied in high school for being so different, and in a way, as adults, we’ve become the bullies because we look back at our high school selves and make fun of the way we dressed, the way we talked, our hair, whatever. And so we really tried to move our language away from that, and that’s been interesting to explore publicly, at events and with the press. I think for a lot of queer women, the cutting of the hair coincides with coming out or the first step in acknowledging that you’re different. And it’s really interesting, especially in our case, when you contextualize it in the ’90s. There was the raver movement, and almost all of the women in our group of friends in high school had short hair. And they were straight. They all had this spiky-razor do. So it was also really weird, because we could absolutely have had short, spiky hair. We wanted to, but we didn’t, because we understood that their short, spiky hair would be perceived differently on us.

It’s a chapter that I went back to over and over again. It was a hard one. I’m not 100 percent sure I was able to put into words how much meaning there is in hair when you’re queer. As soon as we cut our hair, I just felt reborn. People eventually became very fixated on our hair. And after that I definitely thought, Yeah, we should always have a weird haircut. But we were weird. We were in the indie rock world; everybody had weird haircuts. We were one of the more mainstream pop-indie rock bands, so we got a lot of credit… In those moments when we hypothetically advised our younger selves to get a haircut, the advice came from a place of shame. And now I don’t feel that way. I think we cut our hair exactly when we were ready. When we were ready, it was an unveiling.

SQ: I think about hair a lot. Right now I have longer hair, and I’ve been joking that I’m going to keep growing it. Sometimes I feel my hair is a way of being disruptive. Everyone expects me to have short hair. So even when I tell myself I’m going to grow it out more, it’s a way of subverting what people expect of me and being sort of unconventional.

We begged my mom, from the time we could talk, to cut our hair. She finally let us when we were four. I loved it. And I basically had short hair until I got into middle school, and it was very clear to me that to be somewhat successful socially, I needed to grow my hair back out. For some queer people, the first time they cut their hair is in adulthood, but I had already had that experience and had so deeply related to my identity as a young person with short hair, and I was constantly misgendered. I think that in some ways, growing my hair out had nothing to do with my sexuality. It had more to do with not being seen as a boy. Like, I have breasts now and everyone knows I’m a girl. So I need to match my hair to my body. Shaving my head at eighteen was a way of saying, This is the way I want to look and feel. And, weirdly, in those first couple of years after I shaved my head, I got so much attention from guys. I think it’s important to note that it was a look and a style that was popular. I feel like I looked profoundly gay, like I was sort of going out into the world saying, I’m gay! Don’t even try! and yet I was constantly hit on by men. [Laughs] I remember being like, What the fuck?

III. THE GOLDEN CIRCLE

TQ: What became really significant as we wrote High School was a long stretch through the first ten years of our career when we didn’t have anywhere to talk about how hard being queer and being a woman in the industry is. The second half of our career has been almost entirely focused on identity and being queer, and that feels overwhelming at times. Because it’s like, Well, don’t you want to know about our process with music? So there was a weird switch, and the book gave us an opportunity to talk about both halves of our career. In a strange way, I feel like we really used the trauma and the silence that we had to muck through during those first ten years to write the book. As adolescents, I don’t know that we were truly aware of some of the isolation and lack of support from adults that we felt as young women, as well as the internalized homophobia and some of the shame, especially on Sara’s side of the book. And yet that’s such an undertone of the whole book. The book has given us an opportunity to reprocess not just our adolescence but that first big part of our adult life as we came to terms with who we were and created our identity.

BLVR: With the clarity that comes with age and distance, the memoir seems to have allowed you guys to acknowledge what you’d overlooked about yourselves from your individual youthful perspectives. How did the accompanying album, Hey, I’m Just Like You, contribute to that?

TQ: One of the things I was most bewildered by in terms of revisiting the music was how we basically have just rewritten the same song, like, fifty times. The way that we write on the album about relationships and running away—it’s so clear how much of our Tegan and Sara voice we already had in high school but had written off. In terms of the way we layer our voices and the interplay between our vocals and the way we actually write, the length of our verses, the structure of our songs—all of it was developed in high school. And we’ve never known that or spoken about it—and part of it is because we’ve been documented by other people. So we’ve accepted the narratives because we read enough about ourselves in a certain way and were like, “Right. So we figured out who we were from 2003 to 2010.” And it’s like, Nope. That’s just because, to the mainstream reviewers, nothing existed: not our music or our personas. Nobody was writing about that time, and therefore it just disappeared.

BLVR: When I was growing up, there were far fewer gay icons. Ellen [DeGeneres]’s coming out, in 1997, marked time for me in terms of my development or awareness of lesbians in the world. And then another big one for me was The L Word. And you guys. You are referred to as “queer icons.” How did that status dawn on you and what was it like?

TQ: Throughout our career, there have been moments where I recognize our status in terms of where we sit in the community and the influence we’ve had. And then other times, it’s changed. I think we’re really lucky because we got popular, or people recognize us. But I think of how many other queer artists weren’t recognized, and I just shy away from even acknowledging our icon status. I hate it. You have no idea how many times a week I remove icon from our bios, or, I don’t know, the framing of us as that. How many times I fight with managers and record labels; I don’t want to be called that. And then I also want to be seen as that. It’s complicated. I remember two conversations that really stuck out to me after the Pulse shooting in 2016. We were having all these conversations in the press about how upsetting that was and getting a lot of questions like “Well, you’re a queer space too. Do you feel nervous touring because you’re a queer space?” Initially, I didn’t understand that, because I don’t see our show as a queer space. I mean, certainly I think it’s a queer-friendly space. But I’ve always seen us as embraced by the mainstream. And there’re so many straight people that listen to us, because we’re played on the radio and there are so many men in our audience—because we were embraced by the indie rock world and toured for so many years with men. There was this weird stigma that felt factually untrue. And so a part of me was embarrassed, like, “Oh, no you have it wrong. We’re not a queer space.” And there was this whole period of time where I had to come to terms with the fact that for a lot of people we are a queer space and that’s really cool. In the last five or ten years, there have been conversations about the disappearance of queer spaces and queer bars. There’s the feeling that we don’t need those anymore, that queer people are accepted everywhere.

BLVR: I don’t know what to make of that. Gay bars feel very different to me from straight bars.

TQ: A lot of people have talked about how queer women have used music venues and bands as ways to get back to having a community space. So that’s been really interesting to me. And that’s when I start to understand that Tegan and Sara the band has been significant over the last twenty years due to the touring we’ve done and the business we’ve invested in countries outside of North America. Even though outside of North America we’re a much smaller band, we invested time and energy in international touring because we understood how significant it was to create spaces for queer people and women and people outside the mainstream. That will be a big part of our legacy. I also acknowledge how much subtle infiltration we’ve done in the mainstream. Like, for fifteen years now, we’ve played on Grey’s Anatomy and One Tree Hill probably thirty to fifty times; an enormous amount of our music has been used in really, really straight TV. But until the last few years, I just didn’t feel necessarily like a gay band. And I wanted to. I think people assume, “Oh, you’re a gay band. So you must hang out with all the other gay bands and support one another and whatever.” And it’s like, that didn’t happen until recently—I met Melissa Etheridge like two years ago for the first time. I’ve never met Ani DiFranco. Every time there’s a new queer artist, even though they often don’t even know who we are, I just reach out: “Hi, we’re Tegan and Sara. We’re a band. We love you. If you ever need anything, let us know.” It’s something that Sara and I made a huge effort to do. It was a weird thing where every once in a while someone would say that we are beloved in the gay community. And I’m like, “Yeah, I don’t know, are we?” I don’t mean that in a mean way. But we hadn’t been in the golden circle, necessarily, either.

BLVR: What’s the golden circle?

TQ: The Advocate and Out [magazines] and GLAAD [the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation] and the HRC [Human Rights Campaign]. They tend to give their awards to straight women. Which is really cool, because as we know, when you’re a marginalized community, you need your allies. So there’s been a huge focus on allies. We celebrate Carly Rae Jepsen and Taylor Swift because when people advocate for us, we embrace them and love them because we need them. Gay people can listen to music outside of music by gay musicians. But as a queer artist, especially from the indie rock world, we weren’t celebrated in that way by the golden circle. Then with [the 2013 album] Heartthrob, we started to really be embraced. I remember we went to Logo’s award show the year Heartthrob came out and all the gay men were like, “We love you guys!” I was like, Wow, something changed. I also really mark that with us being more glam and more feminine. Because it was a real shift.

BLVR: The acknowledgment was notable because it came from gay men?

TQ: I think so, yeah. I don’t think gay women are as organized or as powerful in that way. NPR did a wonderful piece on [our 2007 album] The Con, looking back on it, and they talked to all these young, queer artists about how much influence we had on them. I cried. I was like, Oh my god, I had no idea that we’d had this influence on Hayley Kiyoko and Shura and Snail Mail. It was great to hear it. It was so profound when Taylor Swift said she liked us or when Katy Perry tweeted about us, because it has been so hard at times. That’s why the second we go off the road, we spend our time talking about books and TV and music that influenced us or that we loved because it meant a lot.

BLVR: When you were first signed as teenagers to Neil Young’s label, you did an interview with a gay magazine and you asked the label if it was all right to reveal your sexuality. They gave you the OK, so you did. That feels brave. Can you identify where that bravery came from?

SQ: I think it was a perfect storm around that time because that conversation you’re talking about happened after we got out of high school. In some ways we did start our career sort of closeted, in that we were playing shows and doing press and radio under the cloak of being teenagers. You don’t ask a seventeen-year-old in grade twelve what their sexuality is on CBC Radio, you know. So I think we sort of exploited the fact that people weren’t being very probing initially. We were dealing with baby stuff. And then, I’ll be honest with you, I think what happened was—I don’t know if we would have asked the label, “Is it OK?” or “Should we talk about this?” without the gay press. It was that they brought us gay press that signaled to me that people suspected we were gay and the fact that the label brought it was an indication to me that it was OK. But we still asked for permission. I have asked myself: OK, in a different universe, we don’t get gay press. How long would it have taken for us to eventually have to figure this out? I don’t think it would have been much longer. But I don’t know if coming out to the press was brave. We were really out in our personal lives. We had girlfriends; our parents were fine with it by then. I wasn’t hiding it, but I didn’t yet know how to integrate it. When people asked us about boyfriends, we would say, “We don’t have boyfriends.” And then we’d move on from there. And so I think this was one of those moments where it seemed like the work had been done for us.

TQ: There’ve definitely been points in my adult life in our career where I’ve wanted to blend or not showcase our sexuality or have it be such a focus. Like right now, it’s such a focus, and that’s fine. I’m really embracing it. We’re having a huge wave of embracing queer culture and understanding it and exploring it. But I also think that as an artist and as a creative, there is always this sort of nagging alarm: like, by embracing this and talking about this openly, am I sending out signals to anyone not like me that say, This is not for you? Because I’m trying not to deter everyone by constantly focusing on this one part of me that makes me different. It does make me different, sure. But love is not different, and relationships are not different, and heartbreaks are not different.