You already know this story. A massive global pandemic strikes. The US ignores the danger for too long, under the assumption that nothing like that could ever happen here, and then suddenly everyone everywhere is infected. Stay-at-home orders come too late for hundreds of thousands of people who must run the course of the illness, which can be fatal or at very least have long-term physical and neurological affects. You know this story because we all are living it right now.

It also happens to be the plot of the novel I have been writing for nine years.

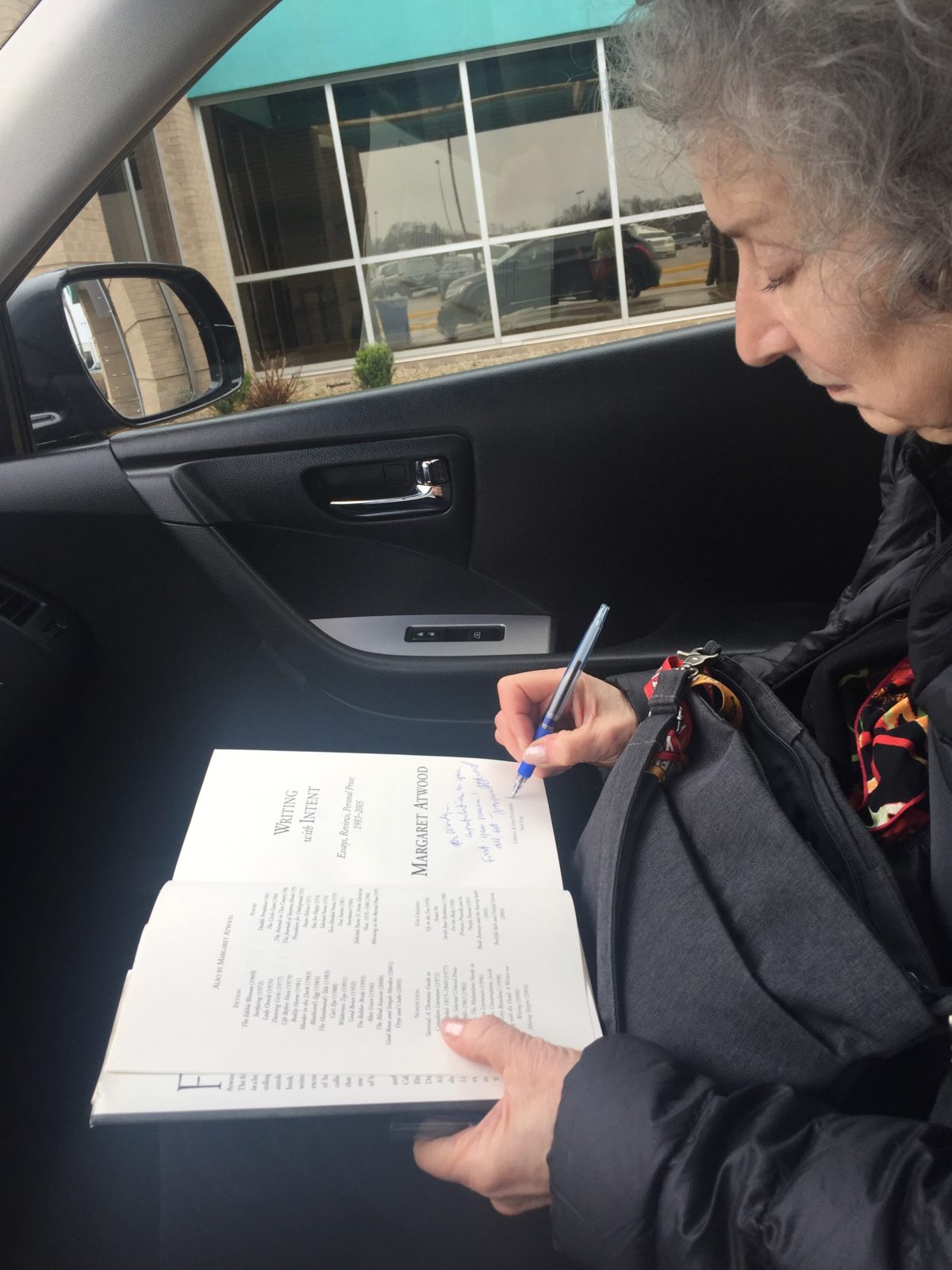

A few years ago, I was Margaret Atwood’s point person for a literary festival in my hometown, and had the fantastic gift of spending some quiet time with her while I drove us from place to place. I didn’t want to be That Person who keeps talking about her work—or my work—after she had faced hundreds of people and a long signing line. So instead we talked about waterfowl, and the seasonal differences between Toronto and northeastern Wisconsin. As I drove along the Fox River, through the late spring fog that had settled over the valley, the landscape felt very much like the setting of a dystopia, except we were seated in comfort, on leather seats with warming elements. I pointed to a spot where I typically saw bald eagles, and brought up the American white pelican, recently returned after a harsh winter. She offered some obscure bird trivia and after I countered with other weird bird facts, she said, “You seem to know a lot about migratory birds for someone who organizes book festivals.” I told her that I was in the midst of researching bird migration for my pandemic novel. She directed her cold steely focus upon me and said, “Go on.”

I felt a bit like a field mouse noticed by a hungry falcon, but when Margaret Atwood tells you to talk, you talk. “It’s kind of a You’ve Got Mail mixed with The Walking Dead and a little Jaws thrown in,” I said. Then I told her how inspired I was by her own dystopias. Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale had premiered that week, so everyone was talking about the political elements of dystopias. Atwood pointed out that Gilead, the novel’s totalitarian patriarchal theocracy, was brought about by a disaster of environmental or medical origin, which she had based on other historical disasters that she’d studied. In other words, everything she had written about had happened before. She encouraged me to look to history for my work too, real pandemics and real quarantines. I had fallen in love with the way her characters react to and against disasters in her dystopias. The atrocities feel earned at a visceral level and that, I told her, was exactly what I wanted in my own work. I added that I couldn’t eat shrimp for almost a decade after reading The Year of the Flood, a novel in which the protagonist sustains herself by foraging for fly larva and notes that they have a similar look and consistency to shrimp. She nodded and responded, “Maybe you wouldn’t do very well in the apocalypse.” I concurred. I have no doubt that I will be part of the first wave taken out, despite all the research I put into plotting my own survival.

My pandemic novel was inspired by two certainties. The first is that when the next extinction struck, it would all play out on social media. It would be a shared apocalypse, with likes, retweets, and memes. The other idea was that zombie movies are essentially pandemic stories. Zombie movies are set in universes that are just like our world except for one fact: in zombie movie universes, no one has ever seen a zombie movie. If they had, they’d see what was going on right away and know exactly what to do: suit up and start whacking zombies until all the bodies hit the floor. These are all survivor fantasies grounded in xenophobia and violence. Movies and comics like Zombieland, Night of the Living Dead, The Walking Dead and The Dead Don’t Die suggest that, in the face of a mounting virus, violence against a specific race—the infected, the undead, the source of whatever pandemic is raging—is the only way to make it out alive.

From those two threads, my novel was born. What if there were a global pandemic that presented much like a zombie outbreak, but what if those “zombies” were just legitimately sick moms, dads, uncles and store clerks? And what if decades of zombie movies have trained us to survive a lurching zombie hoard with “double taps” and double barrel shotguns. And for those who didn’t resort to violence, how would that go? Especially those of us whose primary response to scary and unsettling world events is to make a sarcastic joke on Twitter.

It wasn’t especially prescient that I chose to write about a pandemic. I wanted to focus on how well people do when the bounds of society abandon them. After all, I grew up reading solitary survival stories—from Jean Craighead George’s stunning Julie and the Wolves to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter to Scott O’Dell’s beautiful Island of the Blue Dolphins to V. C. Andrews’s plots about children alienated from society (either tucked in the attic of a large house by their abusive relatives or whisked off to the mountains in Appalachia).

In late August 2019, I sent most of the novel to my doctoral advisor, novelist Douglas Unger, who encouraged me to push a little further in the final denouement. Then I had a long chat with novelist Maile Chapman in a French café about what it would feel like to be locked down in a single place, afraid of catching a virus people knew little about. We talked a lot about how Katherine Ann Porter’s short story “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” explored business as usual life and romance in the midst of a global infection.

Once finished with the final polish on 124,000 words, I started my query letter for agents. But then it was early 2020 and as we all know too well, an actual pandemic started building and spreading and by then my speculative fiction was no longer speculative.

I watched as my friends on social media began to emulate and in some cases repeat verbatim conversations that my characters had in the novel. I had spent months refining the wording of fictional social media posts only to see exactly the same joke and the same tone be repeated on Reddit’s Shower Thoughts forum. After years of tempering down the insanity of my novel because it seemed too much to be believed, the reality was in some ways far worse, in terms of the scale of the pandemic, and our refusal to take scientific evidence seriously. My characters stay inside. They don’t order pizzas because they can’t: my novel’s fictional business owners won’t risk the safety of their staff to deliver a $30 pizza order.

I have spent the resulting months irritated that I was beat to my own punch lines. Despite my own pessimism, in building a fictional pandemic where I thought I’d made everything go wrong, really not enough had gone wrong in comparison to the real thing. My fictional global pandemic was well in hand after just 120 days by the end of the novel, but here we all are.

Speculative components of Atwood’s own novels continue to come true, from Oryx and Crake’s fluorescing bunnies and lab-grown meat to the crackdown on abortion rights presaged in The Handmaid’s Tale. Now I wish I could take another drive with her again and ask her about the things in her work that came true before she managed to get the book to print. Perhaps she’d have a solid answer. Or maybe she’d point out that everything that ever happened in human history is bound to happen again. As a writer, that’s both comforting and terrifying, but at least I don’t have to worry about spoilers anymore.