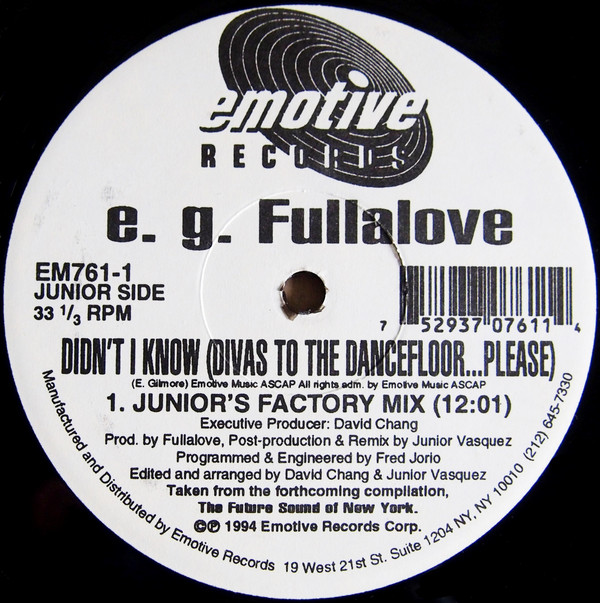

It always felt as if the chosen were being called by some mysterious but benevolent power. It could be heard at the end of the party in the early morning, somewhere at one of the legendary nightclubs in New York City: Sound Factory, The Warehouse, The Tunnel, Limelight, Café con Leche. Before that and out of historical earshot, similar tunes had consecrated founding temples like Paradise Garage or The Loft, storied venues that housed Black and brown gay, lesbian, and trans people desperate to find the lower frequencies in bankrupt 1970s New York. It was reserved for the twilight hours, the time of the late-arriving or slow-to-depart acolyte or disciple. It was the moment for ritual movement, for a fixing ceremony among the initiated. Prior to Kelis summoning all those boys to that impossibly saccharine yard, E. G. Fullalove’s Didn’t I Know? (Divas to the Dance Floor… Please) extended a steely invitation to have house music not so much dress you in the silk Toni Morrison imagined as the healing power characteristic of black church tenors, but rather allow this secular yet sanctified sound to augment or highlight whatever garment your grown self had fashioned or procured.

I found that different level of experience, where ecstatic black queerness resides and enlivens, in the post-pandemic days of the mid-1990s. The latex generation emerged into a world reeling from the genocidal impulses of a nation that had allowed AIDS to ravage and depopulate particular communities for over a decade. But the spectacle and soundtrack of (black) queer nightlife provided balm and sustenance for my searching and fearful self, who fleetingly wondered whether the plague that had befallen the community I was now entering was divine wrath or societal circumstance. There was destined to be little handwringing about this question, just as there was no time or patience for hesitation during that fateful conversation I had with my identical twin brother a few years before, in the stairwell of our apartment building, concerning our shared condition. Refusing the spiritual lockdown that consigns so many to unremarkable sterility, aridness, and personal betrayal, Andrew fanned away my confused tears in pointed if nondramatic fashion, admonishing me to stop crying about something we had both always known, and were only just confirming. It turned out he was already saved, a congregant of that sonic church. Concerned about the real dangers of saying yes to one’s own life, Andrew assimilated music and queer sociality as necessarily fortifying.

My twin, this truly queer pioneer, a former colonial Catholic schoolboy from Jamaica, had been secretly attending meetings and hanging in cafes with writers aspiring and established since we had both returned to the city following brief dispersals to different colleges upstate. We had arrived salty and disaffected from small, apparently bucolic towns with Main Streets chock full of hostile or self-conscious townies, gaudy bric-a-brac, and dive bars frequented by newly liberated adolescents. We were angry with each other. He did not yet know how to tell me that all those girlfriends, all that toxic running around with basketball players was simply cover; I was heated over his reckless and wanton abandonment of our tacit agreement and was now preoccupied with plotting my solitary queer future. I won’t get into the deep spiritual and cosmological symbolism attached to twins, but it’s a profound bond. We founded and refined our peculiar language, anticipated thoughts, communicated with looks.

Andrew interrupted that brief but disconcerting period of mutual misapprehension with surgical precision, spontaneously launching the question; I returned with the briefly halting but finally corroborating reply. After this we would hit the streets regularly, especially on Saturdays. He had already cleared some fitful adult ground with our parents, who now only demonstrated intermittent displeasure with the late-morning turning of the key in the side door and were somehow quieted and soothed by the hushed management of its weight. After an ambitious breakfast, we bounded out through the gates of our sealed-off community on the hill, through the park, out into the hum and flurry of Fordham Road, and then down to Jerome Avenue, where we browsed well-organized garments at one particular Salvation Army for what we planned to feature in the small hours of the next morning. An enormous amount of what Audre Lorde understood as “care and energy” went into what Andrew and I took to be black/bohemian/house-head/writerly early-Sunday-morning fashionable. (The barbershop on Webster Avenue, perilous and exciting as it was then, deserves its own extended consideration.) I witnessed a great deal of repressed pain and desire in those spaces, buffered and held in tense check by the music all straight, homosocial venues require.

There is a certain quality of sun, and a particular quiet, that brings to mind the sense memory of coming home from Sound Factory on a Sunday morning. It is gossamer and electric, stripped of shameful association. The cellphone footage of an isolated scene from Junior Vasquez’s 2015 comeback set at the Arena nightclub in Hollywood is compelling not so much for the sustained glimpses of NYC mainstays like Kevin Aviance and Josè Xtravaganza moving to Vasquez’s surprisingly uninspired remix of Fullalove’s classic, but because it conjures that familiar democratizing, sometimes category-defying energy that can settle over dance floors in the early morning. Mirroring the diasporic ritual of possession, the members of this church have decided to plead the blood at this hour, governed by sound and whatever other liberatory spells they might be under.

The twins can dance, but they can’t vogue! Andrew and I always insisted on being unaffiliated, on fashioning our own particular grammar and syntax, so we took the bodily observation as a compliment coming from somewhere in the direction of the House of Revlon or Xtravaganza. Eyes fierce, heads straight, knees up and running point, shoulders back and narrating, we were there to bear witness. We queer spirits slashed the air with hands, shoulders, and feet—with hips transmitting coded messages punctuating the beat.

Bundha-lahah-lahah: slay her!

Bundha-lahah

I’ll push her down baaack-waards.

We can be sure it saves lives and makes money, but the neoliberal incorporation of this remarkable journey as depicted on, say, RuPaul’s Drag Race or Pose too often flattens out, cheapens, and glosses up the lives and energies lost pre-pandemic to gentrification and reckless overdevelopment. There’s more to tell here about how my brother and I can’t find our frequency again, this time chiefly due to the drudgery of racialized wage labor, the profound failure of American psychiatry, and the promise and inadequacy of drugs—over the counter or illicit. The violence of this world means Andrew can’t quite “keep his feet down here,” as he always described the struggle for psychic balance. And although it hurts to be severed from his remarkable love and power, now twisted and turned inward, knowing he is selfishly at large in this hostile world has to matter less and less—especially if I can still hear the song and conjure it as calling.

— Rich Blint

New York City, day 143