I was in Pie Town when I began to realize everything was breaking down. Two or three days earlier I had driven west from Houston with a small potted saguaro, plotting a new photography project that might someday be called I Took My Cactus to the Desert. In the desolate, timeless flatness of West Texas it was pretty easy to turn up the music and lean into ignorance, to feign obliviousness to the bad news beginning to blanket social media. But on March 13, as I pulled into a volcanic New Mexico campground called Valley of Fires, I remember thinking just this seems right. I parked, climbed to the rear of my car, and read a text message. “BUCKY,” it said, “Nick just realized that you’re going to be in Pie Town on Pi Day.” “Wow,” I think I said in response.

According to the signs, Pie Town was founded in the 1920s, built around a pie-serving rest stop for travelers along what would become Highway 60. Today it has about 180 people and at least two pie shops—the famous one and the other one, plus a third that seemed long-shuttered at the time of my visit—a couple houses, and a concrete-slab basketball court flanked by signs advertising the annual Pie Festival.

I drove in from Valley of Fires on Pi Day morning, past the Very Large Array, intending to have breakfast and then dogleg northeast to Cookietown, Oklahoma. I made a few bad pictures at a dirt cemetery and got chased by a dog that charged at me full tilt from behind a water tower before suddenly pulling up at some invisible boundary. Then I went for pie. A man on the Pie-O-Neer patio wearing wraparound sunglasses and a surgical mask—the first sign I saw of the pandemic—asked me to sanitize my hands before I entered the restaurant. I accepted a squirt and he handed me a sticker advertising his THC chocolate brand’s Instagram account. At the register I purchased a slice of New Mexico apple pie, which had Hatch green chilis, from a woman whose portrait hung on the wall behind her. All the while, anxiety was beginning to bubble. Through the front door came the surprisingly numerous, disproportionately tie-dye-clad Pi Day tourists. I ate. Refreshing Twitter constantly, regretting my decision to travel, I got a second slice. Something with chocolate and red chilis. That was the last food I had from a restaurant, and part of me wishes to keep it that way.

I left Pie-O-Neer, left Pie Town. Some strange autopilot drove me out onto a dirt road. I saw a cow, deleted Twitter from my phone, walked to a mountaintop from which I could see no trace of humanity, texted friends, and worried. Cookietown would have to wait. I slept a little and read some Lonesome Dove. Then, finding the highway, I drove back to Houston. For the majority of that fourteen-hour drive, when not consuming podcast dread, I entrenched myself in the comfort of Gruff Rhys’ 2014 record American Interior on repeat.

American Interior is an odd one, maybe a little like Hank Williams would sound if he were from Pembrokeshire and toured with a puppet and a drum machine. It’s a travelogue that radiates both warmth and longing, perhaps the ideal road trip album for a confounding time when road trips are poor decisions. Rhys, also the frontman of Super Furry Animals, made it after learning he was a descendant of the explorer Johnathan Evans, who had traveled to America from Wales in the 1790s in search of rumored Welsh-speaking Native Americans. The trip did not go well. Evans died in New Orleans. Centuries later, Rhys came to the states to retrace his ancestor’s steps, accompanied by a custom-made puppet of the explorer—a fact that seems to reaffirm many of my own life choices every time I recall it. Rhys made a film, a book, and a record about the trip. The songs that came to make up the record interweave both men’s travels through a variety of stylistic shifts as Rhys sings of loneliness, cartography, and the need to keep existing in spite of the inevitable chanciness of plans.

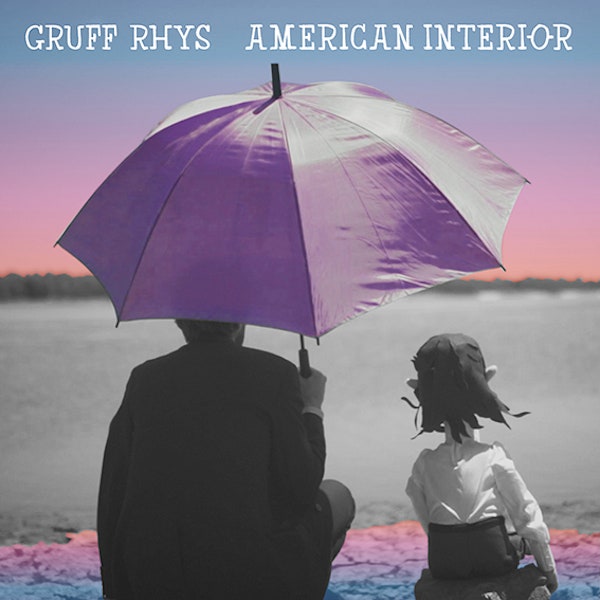

My love for this record is personal almost beyond reason, a feeling I rarely hold for music. Its two protagonists have come to feel like my friends, maybe because of how effortlessly Rhys erases the temporal distance between them. This is a sweet erasure that begins on the album’s cover—man and puppet, backs to the camera, share an umbrella as they gaze across water at the sherbet-to-different-sherbet gradient of an imaginary American sunset. Then there are the rollicking, heartachy songs: On “100 Unread Messages,” for instance, Rhys sings of the hopeless wait for a transmission from the long-dead Evans (“You said that you loved me / I knew it wasn’t true”) while simultaneously recounting, point-by-point, of the latter’s journey. By the time we get to “The Last Conquistador” a few tracks later—“My route was clear but a cloud fell upon me / stepped into darkness, only stars left to guide me”—Rhys’s identity, or at least his quest, has effectively blurred into Evans’s. The breakdown of these barriers gives me permission to step into the mix: John, Gruff, and me, all searching for our own thing. We all come up empty, feel perhaps a little silly, but Rhys has found a way to bind us together and make it alright.

I first encountered American Interior in 2015 as an exchange student at the Royal College of Art. A recent arrival from the University of Texas, I didn’t know where I was. I was homesick. So I got a ticket to see Yo La Tengo in Shepherd’s Bush, and the opening act happened to be Rhys and his Evans puppet, with some sort of didactic cue-card setup to help the audience along. I was enthralled, giddy, and spent the next few months wandering around London thinking about the man with the puppet, listening to the record over and over in my temporary bedroom. On one occasion I turned it off and went for a long walk. Whole Foods was closed so I did a manic lonesome dance through the crowds of Piccadilly Circus: a cartoon of a solitary American in a raincoat, stomping with foolish verve past fancy Pizza Hut, while a man with a Welsh accent sang about the Mississippi River. It’s likely I danced past Downing Street. I reached the Thames, sprinted south across Westminster Bridge, moved against the stream of pedestrians and tourists with no objective. As I reached the south bank, a large man in an unmistakable burnt orange University of Texas sweatshirt stood right in my path. I pointed at him without breaking my stride. Somewhere in all this, not knowing stopped mattering. Inside the inescapable, unpredictable world of blind progress—a centuries-long experiment built on some peculiar notions about the nature of life—it was certain I was a very small thing. But dance was on the table.

Now it’s ten in the morning, May 2020. I’m alone in my kitchen in Texas, where I sometimes can’t believe I live, nursing my eye with a washcloth—I have suffered a jalapeño injury while making guacamole for no reason. “The Last Conquistador” is playing from my phone: “A combination of disease and confusion / my whole life’s work was just an illusion.” Hey, I think, ow. A little much during a pandemic. And yet, with some creeping mirth, I concede that I never expected anything but confusion. Death has always just kind of been hanging out in the corner. There’s an animated gif I’ve been sending friends when I can find no choice besides laughter; a cartoon of Death, reclining on his stomach, skull in his palms, dreamily kicking his legs. Tiger Beat stuff. Now Gruff is singing something dancy and Welsh called “Allweddellau Allweddol.” Yeah, I think, of course. Living is a weird privilege, a weird necessity. It’s a strain to imagine what life must have been like when John Evans succumbed to malaria and was interred a few hours’ drive from here, but Rhys permits me a conjecture: it was as chaotic, as beautiful, precious, and terrifying as it is now. Maybe I cherish American Interior in part because it affirms precariousness as an inevitable consequence of being human, but does so with a light enough heart to celebrate the value of the endeavor. It’s wild out here. In here. Even if we must create a puppet of our beloved, we should love. Wiping a tear from my eye—because of the jalapeño, I guess—I pick up my phone. “Walk into the wilderness / walk into the wilderness,” Rhys’s voice repeats from my hands. “Walk into the wilderness.”

— Bucky Miller

Houston, day 70