“I think unlearning is where we are at. I think it is the thing that we can all do. It’s egalitarian. No matter where you were raised, no matter what your economic system, you can all unlearn what you have learned.”

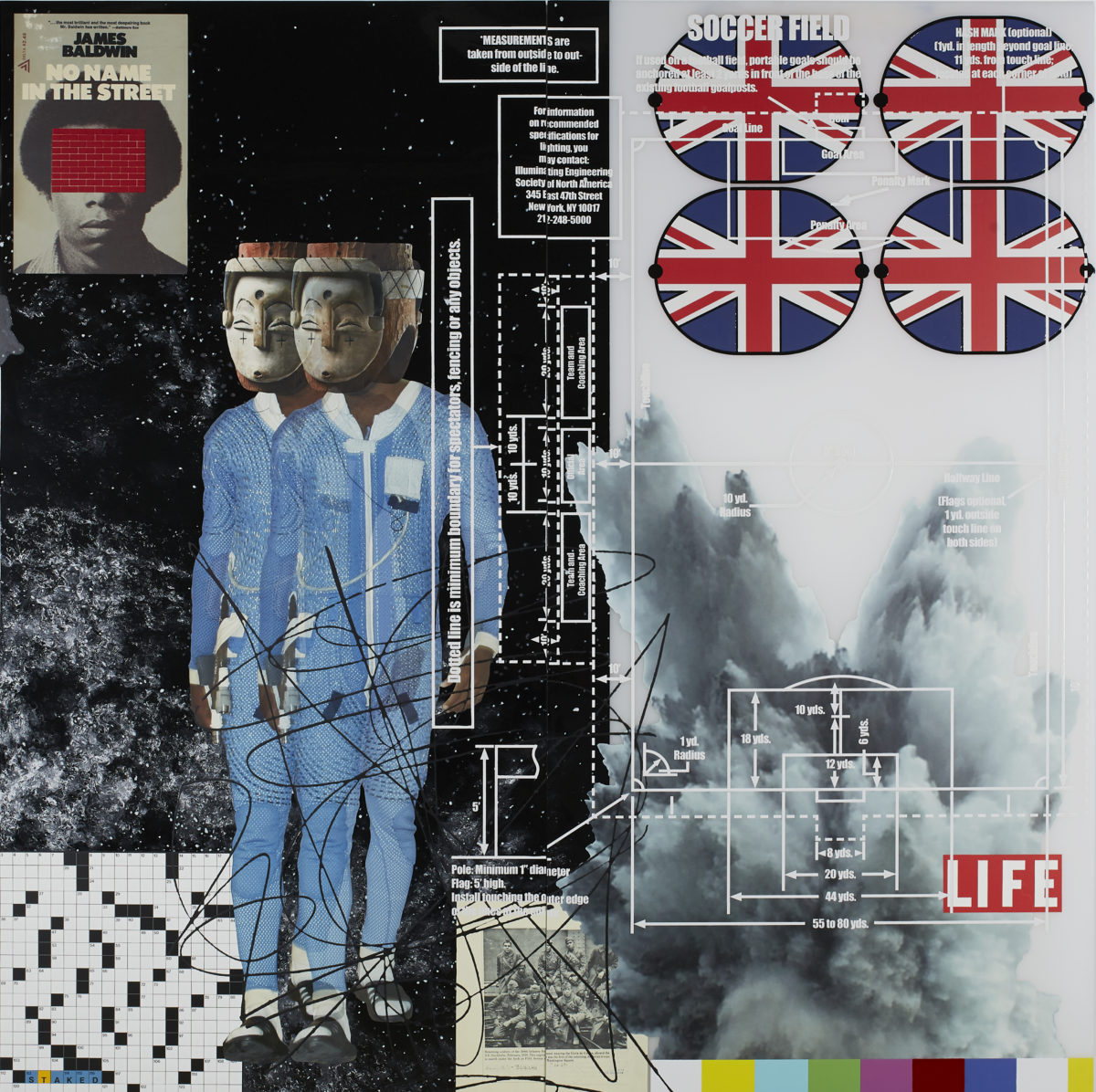

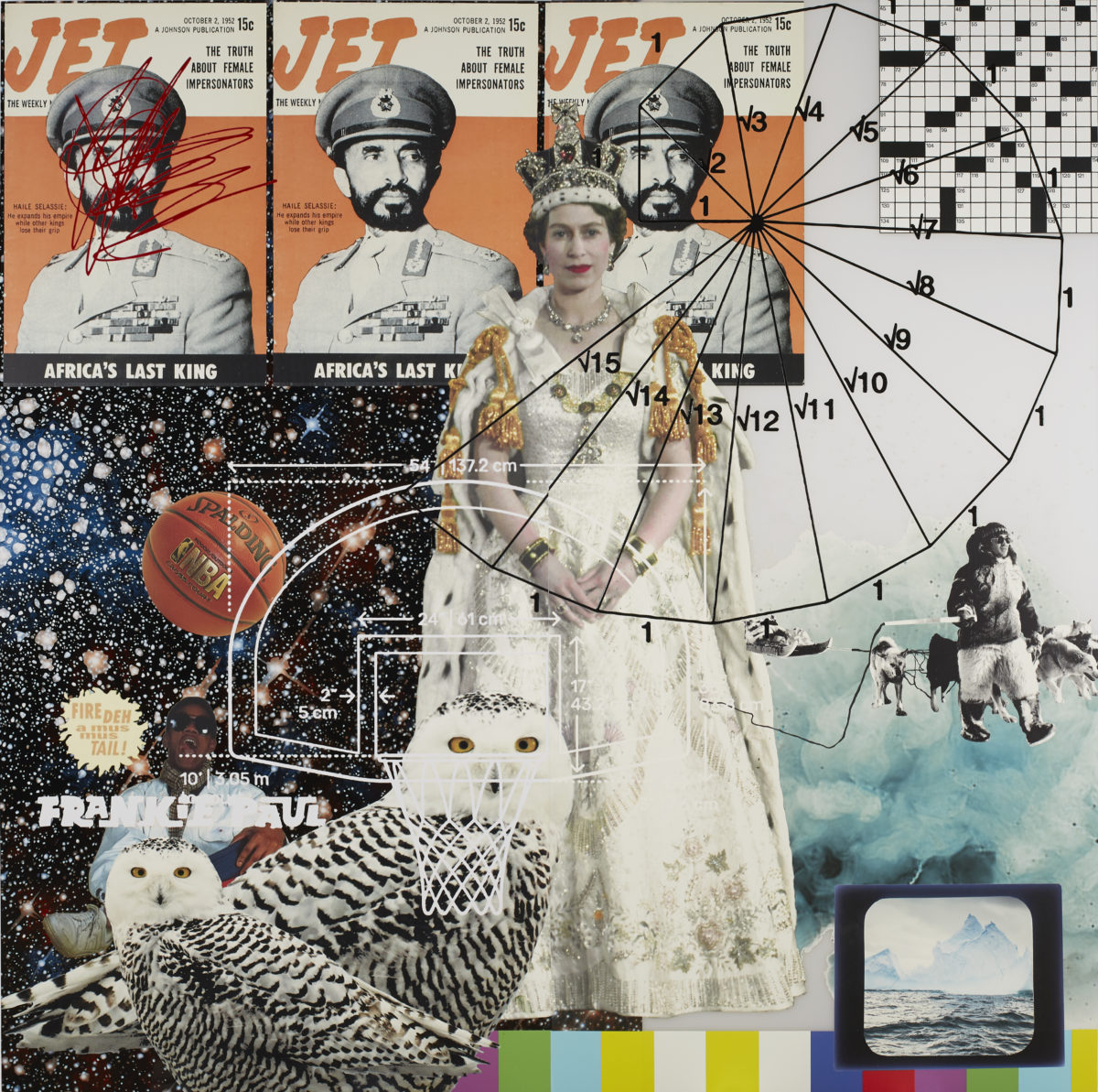

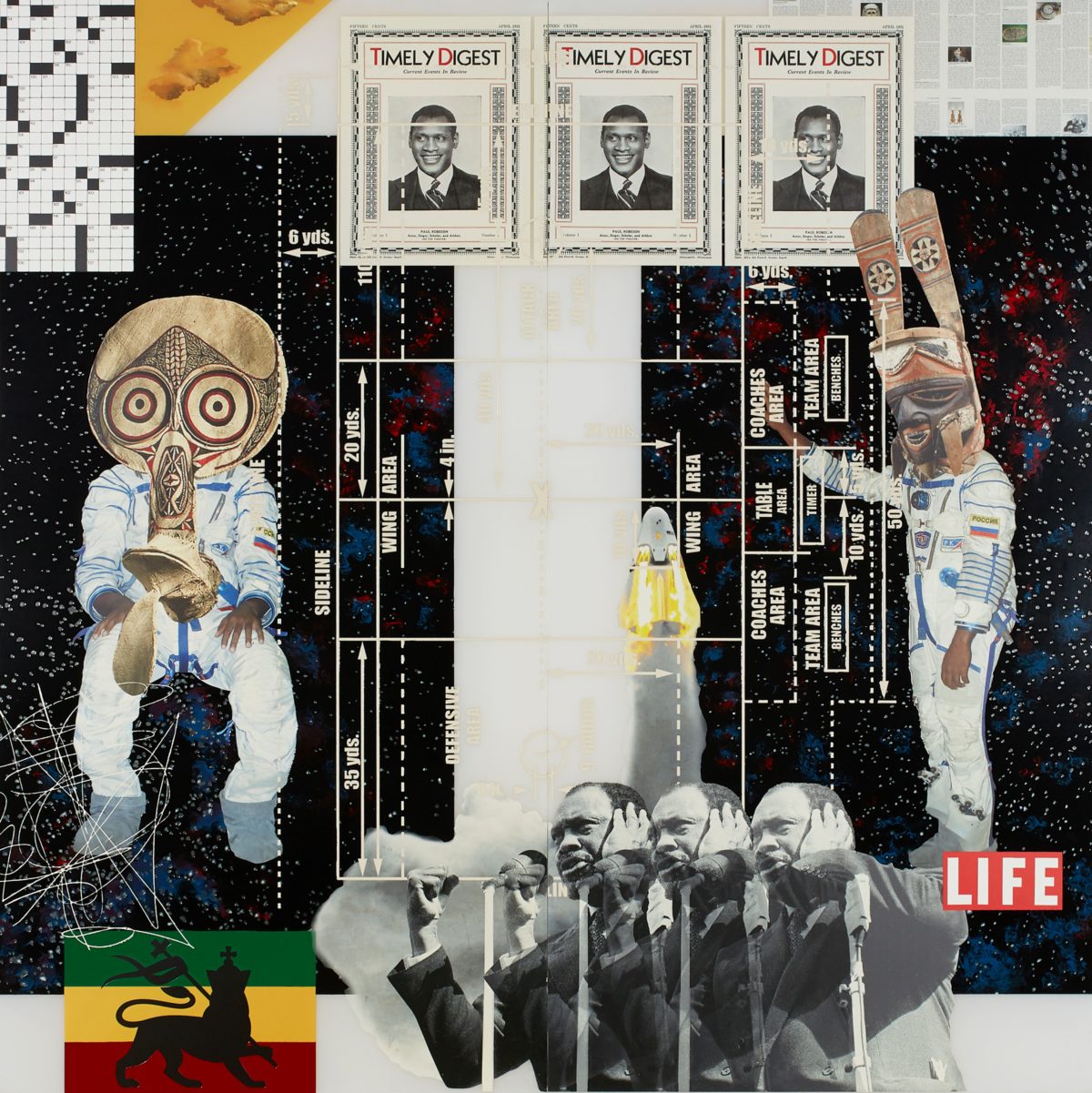

I caught up via video call with the artist Tavares Strachan at his Manhattan studio as he was getting ready to hop on a plane to London for the opening of his first solo exhibition at Marian Goodman, In Plain Sight. Strachan’s work explores the materiality of ecologies across forms and geographies, from the extraction of an ice chunk from the Arctic he then shipped to an elementary school in the Bahamas, to an over-sized blue neon sign reading “You Belong Here,” unfurled across the exterior of Compound––Long Beach’s new art and wellness complex––to the Encyclopedia of Invisibility, which unearths untold and little-known histories of imperialism.

Born in the Bahamas and trained at Yale, Tavares was the featured artist in the first Bahamas National Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale. In 2018, he collaborated with SpaceX to launch Enoch, a golden satellite inspired by Egyptology, into space honoring the first Black astronaut, Dr. Robert Lawrence, Jr.

We chatted about audience, about the child mind, and one of Tavares’ central ideas: the concept of “unlearning”—how we need to unlearn modes of being, thinking, and concepts of what is art-making. We closed our wide-ranging conversation with shared concerns about air travel in these times. I was reassured to hear that there were extensive measures in place to stay safe, including a fanny pack from the airline with gloves, cleaners, masks, and a 14-day quarantine upon arrival. Safe passage.

—Leslie Carol Roberts

THE BELIEVER: In Plain Sight just opened at the Marian Goodman Gallery in London.

TAVARES STRACHAN: It is an exhibition—you’re in a kind of world, it’s roughly 10,000 square feet—and it is about the history of invisibility. It is centered on my project The Encyclopedia of Invisibility, so I am building on that. One of the main installations is a room called Eighteen Ninety. And it is 1400 floor-to-ceiling drawings, all created on pages from the Encyclopedia of Invisibility.

BLVR: Why did you choose the year 1890?

TS: The drawings, pencil, oil sticks, silk screen—all have patents specifically from the year 1890 superimposed on them. In 1890 there were more patents submitted by Black inventors than any other ethnicity. This is the only year it ever happened. In 1890, twelve percent of the population of the United States were Black. But they had more patent submissions than any other kind of person. This was shortly after the abolition of slavery and there was this “exhale” moment and we all know what happens after that.

There was this very specific moment in time: for instance, synthetic cortisone? Synthetic cortisone [vital for its economic accessibility] was invented by a Black person. I think of 1890 as this really magical moment in time. A kind of apparition, right? And I wanted to figure out a way to talk about this super-magical moment that was a blip or sweet spot in America where slavery was just abolished and there was so much imagination—so much trapped imagination being released into the world. And how much fear that imagination brought on to America and had to be suppressed and shortly after that, there was segregation and Jim Crow, right after that. All this advancement in Black intelligentsia was rolled back immediately.

BLVR: You referenced how this instantiated racism and oppression—“fortunately and unfortunately” were your words—also emerged in other forms of creativity.

TS: It brought rock and roll, it brought reggae, it brought hip hop—because all of these other things started to roll back. And these folks were forced to be creative in these other ways. When, for example, musical instruments were all being removed from schools in the Bronx, this was a huge part of the reason hip hop was invented there. So you think about these kinds of parallels between this kind of apparition of a moment in time and then its relationship to creativity and invention. And also your relationship to what you are told as a child. You never hear about 1890! Why do we not hear about 1890? When there were less Black folk and more creative inventions by Black folk than anybody else—right after being enslaved!

BLVR: Were there any particular patents that captured your imagination?

TS: The light bulb! The light bulb was greatly improved upon by a Black inventor. All kinds of things.

BLVR: I feel like this is a book that has to be made: the 1890 book! That feels like it would do more to unpin these tethered white histories and timelines and change the cadence of how we learn.

We were also talking about what statements of solidarity with Black Lives Matter that corporations like Chipotle have made—along with artists, politicians, colleges, and on and on.

TS: I feel like the statement thing acquiesces a little too much to social media culture and speed. It’s more rhetorical and less action-based. Statements are like,”Hear what I say and then I am going to do something different.” Which is what most people do, anyway.

BLVR: Your work “We Are In This Together” is slated to open in Telluride this autumn, to be in place on the mountain for eighteen months. It’s a neon pink public art installation: a statement in words that are fifty feet wide at their widest point.

TS: The project started five years ago with the Ah Haa School for the Arts and the Telluride Foundation, and it kind of grew into this conceptual idea surrounding this phrase, “We are all in this together,” which, since then, has taken on a new series of meanings in popular culture. This was around the idea of these “statements.” Overreaching statements that, if you have to say them, obviously mean the opposite. That’s the genesis of that work. I think it’s connected to all the other text-based work that I have been interested in over the past couple of years. I chose pink because it’s a color I grew up with, and it seems harmless.

BLVR: Pink was also the color used by British colonial map makers to designate the British Empire so the maps they made showed their sovereignty in a pale shade of pink. Is this also part of the reference?

TS: I think I am always referencing those kinds of intertwined histories. And by intertwined I mean—you know, my name is Tavares, and this is a West African name originally that was adopted by the Portugese. My last name is Strachan, which is a Scottish name. So I am kind of a living testament to an intertwined nature of the East and West—a new iteration of a post-colonial-ish human.

BLVR: What were the challenges of the construction, the materiality of the sculpture in that ecology of ice and snow?

TS: I think ecology is always hard, just because—and maybe I am going to go a little meta-, but it’s hard to be human without fucking things up. And the only way to do it is to become closer to the system or environment that you are spending time in and living in. We—myself included—have had a hard time doing that. I mean the pandemic is obviously the result of human imbalance in the natural world. Animals are being pushed out. I just read this article about how when animals are pushed out of their natural environment, the stress produces more virus variations and the viral load increases in those animals, those creatures, and it makes them more susceptible to pass them on to humans. Deforestation, for example, is one of the reasons one of the arguments to why we have all of these viruses.

BLVR: The iterative nature of your work and the range and scope that your work traverses—you have the heart and soul of an explorer.

TS: It’s hard to talk about because—I was raised in the Bahamas then moved to the States to train. Training is deeply problematic, especially in academia—because you learn how to put things into categories. And I think all of those categories are difficult and deeply problematic. The thing that was attractive to me about being an artist is that you were told you could do whatever you wanted—and one of the things that I wanted to do was not put things into categories. And being an explorer allows you to do that. Because a huge part of exploration is blindly going into things. And I think that is deeply connected to the idea of “unlearning.”

BLVR: Unlearning? That’s beautiful!

TS: I think unlearning is where we are at. I think it is the thing that we can all do. It’s egalitarian. No matter where you were raised, no matter what your economic system, you can all unlearn what you have learned. Or at least try. So the exploration part of my practice is, along with the other parts of it, has a lot to do with unlearning. There is an infinite game I am interested in, and I think the infinite game I think parts of the story I am trying to tell.

BLVR: You mentioned a “failure mechanism” built into how you work?

TS: Because I am moving around a lot in my practice, it makes it more difficult to have a cohesive story. Maybe in twenty-five years, it might be possible to have a more cohesive story? And I think that there is a built-in risk involved in that. Because the opportunities in this way of work creates much more vast opportunities for misunderstanding, working this way. This is the unlearning part and I think the misunderstanding is the unlearning part for me.

BLVR: You take on and challenge the notion of “expertise”—for instance in the work you have done with SpaceX—how you trained as a Cosmonaut, then were in residence at the Allen Institute in Seattle while developing your work Enoch, which then was launched into orbit?

TS: The Enoch project I did with the LA Country Museum and SpaceX—was inspired by the ancient Egyptians and Egyptology, and thinking deeply about time travel—and the ancient Egyptians notions of time travel and space travel and the afterlife—a kind of disembodied reality, the idea of gatekeepers to the physical and spiritual world. Those Egyptian histories allowed me to think more elastically about contemporary narratives like Robert Lawrence’s story. [Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., PhD, was the first African American astronaut. He died in a training accident in 1967, without ever reaching space. Recognition for Lawrence was slow to come in the years afterward.]

BLVR: So you create a world where Robert Lawrence can go to space, at last.

TS: How you can think about the past tense as active—most of what you learn about the past tense is that it is Stoic and fixed. But if you think about it the way the ancient Egyptians think about it, it’s all malleable. So then it is possible to put someone into space who hasn’t gone when they were actively alive. And so it connects to this kind of hidden histories idea, but it also connects to the power of being able to think about time as more malleable and less fixed and linear. So there is a certain power in that. It allows someone like me who is very much a byproduct of the “colonial project” to have a lens outside of just trauma. I think this is one of the things I am interested in: How do people who look like me escape the dimension of trauma and find these other ways to find voice and reconnect with one’s history.

BLVR: It sounds like SpaceX was an ideal collaborator.

TS: From the jump SpaceX was told by the experts—all the technologies they were developing—they could not do it. But they just keep pressing on. I think one of the more interesting parts of the Enoch project was how seamless the conversation was with SpaceX. They heard the idea and said, let’s do it. They are very radical and you know for years they were told they couldn’t do what they intended—but they kept at it anyway. It’s very expensive and time consuming to do these things so the fact that they saw the value in this was really a testament to them and their willingness to collaborate. Their practice is as close to art-making as you can get on an industrial level. They push constantly. Which is kind of the history of art process.

BLVR: From the earliest days of your art making, you have explored ecologies and histories—in 2008 you extracted a chunk of Arctic ice and shipped it via FedEx to your elementary school in the Bahamas, where it was displayed in a solar powered freezer.

TS: I am from a place where if you wear an orange shirt, you are a radical. It can be that conservative. It was important to me to put this object at this school and speak to my five-year-old, seven-year-old, eight-year-old self—because those were the kinds of things I was curious about then. I know that’s a reductive explanation for the motivations, but it taught me so much about myself and my community. The weight, the density, the fragility—using the sun to keep the ice kind of intact.

BLVR: And it was key to work with the kids?

TS: They were fully on a journey with me, about a kind of flipping the colonial lens around – we are used to people coming to visit us on the island. We are used to the idea of thinking about the explorer as other. And so what happens when you become the explorer?

BLVR: Sometimes I teach young kids about writing and I am always struck by how much they love their work and want to share it, as opposed to college and graduate students who often introduce their work by stating it’s not good.

TS: I think my audience are younger people—not that physical person but that mindset, that eight-year-old mindset—and this question of audience has never been articulated to me, while a stuent. I think a huge part of art practice does not give a shit about audience. I think they don’t care about audience. Because I think if you cared about your audience a lot of people would be making things radically differently. What I mean by that, you can have an audience of four people. For me, I can have a school group in the Bahamas be my audience forever. And then everybody else can watch me have that dialogue with them. So it’s not that I am not sharing it with the world, it’s that I am talking to that specific audience and you can participate in that dialogue. And find connection through watching this conversation, so, I think that distinction is really, really important because your audience does not need to be everyone. It shouldn’t be—it should be pointed.