PRINT IS DEAD

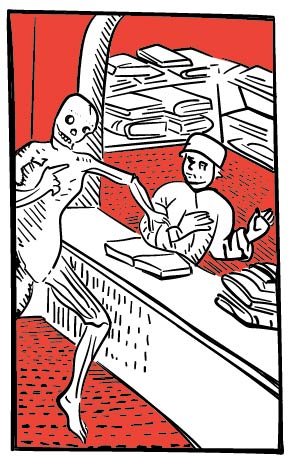

In his late-fifteenth-century woodcut of a danse macabre, Matthias Huss depicts Death striding into a printer’s shop to remind a bookseller and his colleagues of their mortality. When I look at this image now, five centuries later, I find it hard to avoid making a joke that even at the dawn of print, print was dead.

During the COVID-19 crisis, a more serious reading of the woodcut is unavoidable: that reopening a bookstore—or any place people gather—could be fatal. Death comes in looking for a buzzy debut novel, or the latest brief against encroaching fascism, or a collection of poems, and takes a bookseller with him.

DEATH ENERGY

In Rebel Bookseller, his memoir and how-to, Andrew Laties tells the prospective bookseller that “you can focus on the fact that your independent bookstore is doomed and then let this reality prevent you from launching the thing. Or you can focus on your doom and use this foreknowledge to help you plan for finessing your business’s reincarnation.”

He refers to this feeling as “death energy,” taken from a Buddhist concept of the greater truth beyond the ephemeral nature of all human endeavor. I think of this concept often these days at my store, in Point Reyes, California, trying to harness this energy in the midst of a crisis to receive and sort books, to pack and weigh and ship parcels, to wheel the handcart to the post office and return to start the process over again. There is something mind-numbing in the tedium of these tasks, a lack of variation that’s so unlike bookselling in so-called normal times, when conversation and connection spark insights or lead to sudden, unexpected relationships. Selling books is not the same as bookselling.

One afternoon during the second month of our store’s closure, I set up my iPhone on a table facing the counter and recorded a time-lapse video as I packed books. I shared it over social media, never expecting that, as of this writing, it would be viewed nearly seven hundred thousand times. Many people saw the act as heroic (and others, to my dismay, as archaic).

It was neither of those things: it was a necessity. It was a bookseller harnessing death energy to keep a bookstore going, doomed though it might be.

DAY FIFTY

On the fiftieth day of quarantine, I woke early—not as early as my wife, who, in a truly heroic act, has shifted her schedule to the margins of the day to accommodate two full-time jobs—to the sound of our fifteen-month-old son, Liam, pattering down the hall from the bathroom to our bedroom. He pushes the bedroom door open each morning to ensure that the fixed stars of his universe are still in place—there’s Dada, the cat (“Zoozoo”), the tempting pile of books on the floor, the phone charger, a flashlight, and a pen—before moving along, his steps more stable and efficient by the day. He started walking in mid-March, just as we closed our bookstore.

The world came to a standstill just as he was taking off. It seems that nothing can slow him down.

This is what I tell customers and friends who ask us how things are going: it would be immensely easier to get through these days—both physically and psychically—if we weren’t taking care of a toddler, but it would be so much harder without him. Who else would insist that we dance and sing every day, even as we feel gutted by the news? Who else would give us permission to marvel at the simplest of actions: a dog licking water from a bowl, a deer in the yard?

Liam meets a chicken at a neighbor’s house and the world is made anew.

BOOKSELLING WOULD BE A GREAT JOB IF NOT FOR THE CUSTOMERS

These weeks are exhausting. I would never compare myself to medical professionals, first responders, or grocery store clerks. Still, I feel worn down by the continual adjustments. All the booksellers I talk with feel the same. We watch other stores launch social media book-recommendation hours, “virtual tables” for their websites, Instagram Live story times, online author events. And we feel we should be doing more.

It would be disingenuous to deny that these feelings arise from business interests—we do need sales. But even more, we need to connect people to books—and we need, ourselves, to connect with people. The first principle in this bookseller’s oath is “People over profits.” In the absence of that ability to connect, we feel rudderless.

What good are these sales if they are untethered from the physical fact of the bookstore, a space of gathering and communion?

A STORY IN TWO VOICES

The story of indie bookstores in the twenty-first century must be told in two voices. One voice tells of an endangered species brought back to life by pluck; the other says more humbly: We skirt the same abyss as everyone else. It may appear closer to us than it does to you, but when measuring the distance between here and oblivion, what are a few inches? A few inches. The thickness of, say, War and Peace.

As Point Reyes shut down around us—shops that rely upon foot traffic, like those that sell local handcrafted art and weekend entertainment, had no viable alternative—I continued to go into the store. We were flooded with website orders, just as customers, almost without prompting, rushed to support beloved bookstores across the country.

To sell a book in a store involves conversation, intuition, and deliberation. It involves reading body language and movement—in short, it’s a human enterprise. Selling a book online is purely transactional: A customer may come to that book through your urging, but the complexities and, really, the beauty of that transaction are flattened. You find the book on the shelf and ship it off. The transaction is done.

A SIGN OF ORDER IN THE WORLD

Some mornings I walk into the store, lock the door behind me, and let the burden of all that needs to be done fade away for a moment. I stand in the bookstore and take it in. (Calling it my bookstore feels presumptuous. It’s not mine; it belongs to everyone who walks in.) I don’t love the smell of books (if only we could charge people for exclaiming, “Oh, I love the smell of books!” when they enter), but I do love the sight of them neatly arranged, a glimmer of order in an entropic universe, even as a thin layer of dust has settled on the untouched regions of the store over the past few months.

And then I mentally rearrange the bookstore: shifting tables, removing shelves, culling stock, all in an effort to imagine what browsing a bookstore in a post-pandemic world will be like. How many customers can this small store safely accommodate? How do we disinfect books? Do we disinfect books? How do we ensure social distancing? And masks: Where to begin with masks?

As the days drag on, I find respite from incoming orders and steal some minutes here and there to transform some of the imaginative work into physical work, tending to this neglected and suddenly haunted space. There are moments on these afternoons when, weighed down by uncertainty and despair, I feel an overwhelming desire to dismantle the entire thing, leaving the space empty and, if not pure, then at least receptive to whatever comes next. Because what comes next cannot be what came before.

A THEORY OF BOOKSTORES

A bookstore is a place where daydreams have license to roam. This place, a physical place, is conducive to reverie, to the acquisition of new, unexpected knowledge, to digression and discovery—browsing a good bookstore emulates the squiggly plotlines of Tristram Shandy.

It happens in and of the body, the path you follow through the displays, the fact of the bookshelves—books too low, too high; what’s at eye level sells best, the volumes on the lower shelves marked by dust and neglect. Maintaining this space is a burden that we must bear, carrying hope and disappointment into each experience.

No matter how small the space, a bookstore always remains tantalizingly out of reach. It can never be exhausted. Borges’s library is vast, infinite, but it needn’t be. It could be housed in a closet.

But digression, as many frustrated readers of Tristram Shandy learn, is not efficient—and efficiency is just as much a product as the toilet paper delivered via Amazon Prime. And so when that rare customer complains about a backordered book they bought “to support a local business,” I text a fellow bookseller to ask if they have it in stock and if they’d be willing to trade it for a book they need.

It is not efficient to respond personally to every order with a note of gratitude—or to vent or rant or ask customers how they get through these days. Yet I spend evenings at the dining room table working my way through orders this way, late into the night, feeling it is my obligation, as one human being connecting with another, to eschew the idea of efficiency.

A BOOK SALESMAN

I’ve had enough conversations to know this feeling isn’t unique to me, but I worry about the idea that bookselling is at its purest when there is no one to sell books to.

Perhaps as a form of self-preservation, I call myself a bookseller but never a book salesman. There’s a passiveness to bookseller, a vestige of a noble profession that adheres to the term. A bookseller, in this usage, never treats books as units to be moved. (There are some in this industry whose mere glance can strip away the varnish of mystique that shrouds a book, turning it into a tchotchke or gewgaw, an object that has a price and makes a profit—not much—and a life span based on how many copies it sells per year.)

This isn’t to say a bookseller is a passive component of the great machine of publishing. Though our reach extends only so far, though our light is only so bright—let’s not overstate our importance but, rather, revel in its modest scale—we continually work ourselves to exhaustion to connect readers with books and one another, knowing that a book can alter the course of a life.

It is the humanness of this scale that so appeals to me. It is unfashionable and unsustainable in a world where the rich grow richer by exploiting resources and workers, often conflating the two, but I think the resurgence of bookselling over the past ten years owes much to a desire to remain connected in a fragmenting world.

It is also, like so many other things we love and cherish, perched on the edge of an all-devouring darkness that threatens the lives and livelihoods of millions.

A SILVER LINING

I find myself angling stories toward the positive, perhaps because the alternative, which is truer to what I feel internally, is too difficult to say aloud.

During the introduction for a Zoom event with Merlin Sheldrake and Helen Macdonald—the pair were discussing Sheldrake’s book Entangled Life, a work that explodes ideas of identity as much as it elaborates on the biology of lichen and mushrooms—I mentioned that there are silver linings to virtual events. (Silver lining: an expression I don’t think I’d ever used prior to this occasion—a ready-made phrase, rising up in a moment of need.)

A silver lining: The crisis has given us, a small bookstore in rural Northern California, an opportunity to reach a global audience. It has flattened certain inequities in publishing: an author without a travel budget can now join us for an event, when an in-person visit might not otherwise have been possible. And though a virtual event will never replace the ineffable feeling of a live gathering, where invigorating conversation and collective energy can occasionally create a magic that lingers for days, it can reach unexpected places and fulfill needs that we, booksellers, cannot see or know.

THE HOUR BEFORE

My favorite time in the bookstore: the hour before opening the doors for the day. The store is lit only by soft morning light; here in West Marin, it’s often gauzy as the fog slowly burns off. The shadows angle neatly under the display tables, and a feeling of sanctuary envelops the space. A quietness that’s soon disturbed by conversation and crowds. Not ruined by those things, just interrupted; this interruption is the natural order of things. That quietness is always there, beneath the bustle of commerce, the voices of children, the conversations that arise when people and books meet.