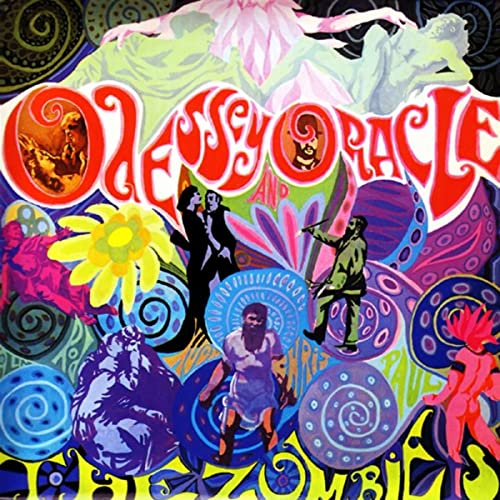

I found it in the discount bin at my local record store, the case so badly cracked that it popped out of place when I picked it up. I’d never heard of The Zombies, or of Odessey and Oracle, but I’m a child of failed hippies, and I couldn’t resist the cover: scrollwork and flowers, a riotous burst of colors, a smattering of dancers, so much lovely chaos that my sentimental teenage heart couldn’t take it. I bought it immediately.

It was 1993 and I was fifteen years old. The year before, my parents had separated, and my father had moved from our home in Kentucky back to Florida, where I had grown up. It would be months before I saw him again. My father was the parent I’d always felt closest to, mostly because he told me constantly how similar we were and I’d grown to believe it. Left alone in a house with my mom and sister who were, at the time, almost like twins themselves, I felt alone and adrift.

For a while, I let the drift take me. I had earned a reputation as the good kid because I got As and rarely talked back. But at fifteen I learned that the key to being the good kid was simply to be so good at deception that you never got caught. It was easier to come home at curfew and sneak out again once my mom was asleep than to come home late, easier to slip out the silent back-porch door than to leave through the kitchen door that creaked. It was easier still to accept alcohol and pot and other means of distraction from someone older, because there is always someone older trying to tempt you when you’re a teenager. Someone older, it turns out, rarely asks if you’re old enough to do the things you’re intent on doing, and the one who sought me out never asked me about myself at all. Like me, they weren’t especially interested in the particulars, and they were good at keeping secrets.

But the problem with being good at not getting caught when you’re a teenager is that you deprive yourself of the kinds of attention that bolster your self-esteem, and become vulnerable to the kind that exploits it. The aimless, furtive things I did in the quiet of that person’s car—not sex but nearly, not illegal but nearly—made me feel fleetingly powerful, but they didn’t make me feel less alone. So I stopped seeing someone older, and turned to my father’s favorite music instead. I burned through his beloved discographies, The Beatles and the Godspell soundtrack and Lynyrd Skynyrd and Jefferson Airplane. All of it sounded hollow without him singing along.

Outside the record store, I ripped open the case and put the tape in my Walkman. When I heard the first warbling notes of “Care of Cell 44,” it sounded close enough to my father’s music to be familiar: cheery and somber at the same time, like The Beach Boys trying to sing a jail-cell door open somewhere. I felt at home in the album’s psychedelic melancholia, so I decided to inhabit it for a while. I wore Doc Martens and my mom’s old cotton gauze blouses, grew my hair out until the ends split. I listened to “A Rose for Emily” and read the Faulkner story of the same name. I pontificated insufferably to anyone who would listen about how The Cranberries’ new album owed The Zombies an incalculable debt.

Not long after, my parents decided to divorce, and my mom started dating again. When her boyfriend began staying the night, I would lie in my bed in the room above them and put a tape of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons in my Walkman to drown out the sounds of them having sex. When they were done, I’d often put in Odessey and Oracle, always side one, and play through until the last notes of “Hung Up on a Dream.” I listened occasionally to other things, but for a while that album was the only one that would help me sleep.

In 2019, in the middle of my own divorce, I started dating another writer I’d met on Twitter, someone who lived across the country. To stay connected, we texted and FaceTimed, and we made each other playlists. The first one he made me was filled with Regina Spektor and The Cure and Liz Phair, songs I loved but had never mentioned. About a dozen songs in, “This Will Be Our Year” from Odessey and Oracle’s B side began to play.

For a moment, I could feel myself at fifteen again. The cool of the cotton sheets on my childhood bed as I lay in the dark, the sounds of my mom and her boyfriend finally settling into sleep below me. The sheer relief of the silence, of the Walkman in my hand. The plastic pop and crack of the hinged tape case as I opened it, the rub of the paper liner between the pads of my fingers, the way I didn’t need to turn on a light because I’d read the Shakespeare quote written there so many times that it echoed in my head:

Be not afraid:

The Isle is full of noises

I remember turning the tape over and running my fingers across side two: “Changes.” “I Want Her She Wants Me.” “This Will Be Our Year.” In all that time listening to that album as a teen, I’d never played side two. I’d heard “This Will Be Our Year” a handful of times on the radio but never played it myself. I hadn’t earned that kind of happiness, I told myself. Nothing had changed. No one wanted me. It wasn’t my year. The A side was for making it through the bad time, the B side for when things were better. But by the time they were, I had moved on to other music.

The Zombies were right, at least for a while: 2019 was our year. I moved out of my ex’s house, got a divorce. I began to feel like a mother to my children again rather than the hired help. I spent hundreds of blissful hours with a person who made every moment feel like there was a future with a thousand possibilities instead of the drudgery of a single one. When I listened to that album last year, especially that song—sometimes alone, sometimes with my fingers threaded through his—I felt peeled back and broken open, past the bad marriage and the even worse divorce, down to the bones of the person who existed before:

And I won’t forget

The way you held me up when I was down

And I won’t forget the way you said,

“Darling I love you”

You gave me faith to go onNow we’re there and we’ve only just begun

This will be our year

Took a long time to come

Every time it played, it felt like my person was whispering to me: My love, you don’t have to earn your happiness. Where it doesn’t exist, you make it.

And then.

And then.

The record store where I bought Odessey and Oracle is closed now. The restaurants I used to park behind with that someone older are all closed too. Instead, there’s pot and alcohol and isolation, all of it easy to come by, all of it familiar. And for now, I’m fifteen again. This time, much of the country is with me. The sadness has ripened, the loneliness multiplied.

I still text my person every day. Most nights we talk or FaceTime for hours. I’m listening to Odessey and Oracle again, all the tracks, often on repeat while I run along empty rural Kentucky side roads. Whenever “This Is Our Year” comes on, a strange thing happens: 2019 plays in my head like the end of Cinema Paradiso. There is kiss after kiss, touch after touch, a montage of all the tiny intimacies and joys that have been taken from us. For a while that reminder was welcome, but now it makes me unbearably sad. Just like you, I’m lonely. Just like you, I’m desperate for the kiss, for the promise, for the future, any future at all, to make itself known.

I’m still, in small part, the same absurdist, sentimental fool I was at fifteen. That flaw makes me believe that someday things will get better. That flaw forced me rework the ending of this essay ten different times to try to write the happy one, but I haven’t been able to write it yet. I try to imagine the After, the person I love in my arms again. I imagine hearing this song. I wonder if it will have the same resonance. This year has made me doubtful. Still, I told you: I’m a fool. I hope, I hope there’s a time again when these lyrics ring even a little bit true.

— Megan Pillow

Louisville, day 171