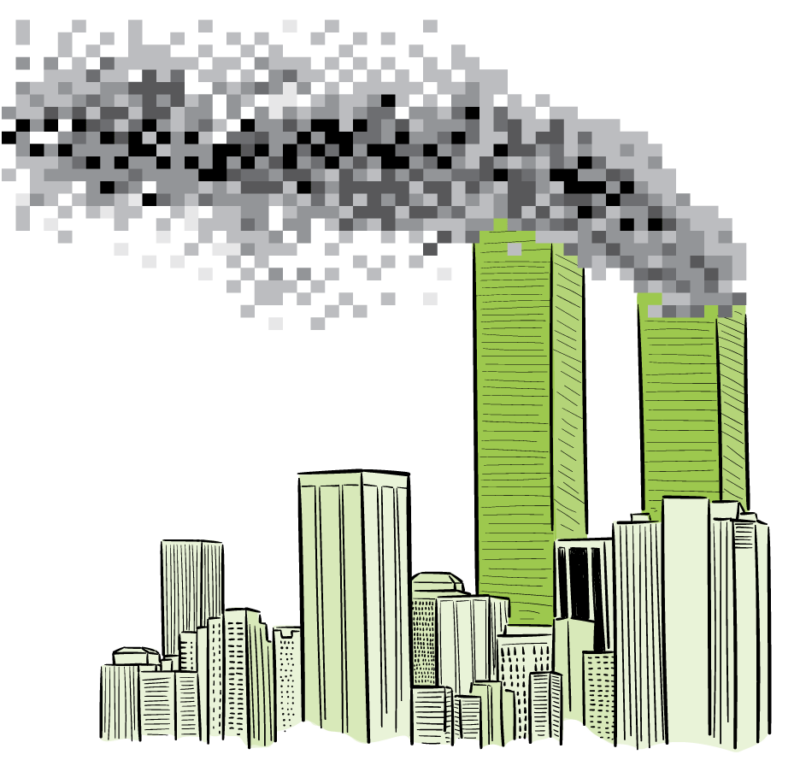

That September morning, I woke up to sounds coming from the alley off my apartment building in Vancouver, British Columbia. Someone down there was shouting in disbelief. Without much concern, I drifted back to sleep, until I heard the telephone ringing: it was my mother urging me to check the news. I switched on my desktop PC (Apple computers were too expensive then), logged on to the pre-paywall New York Times, and watched pixelated digital footage: planes were crashing into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, in Lower Manhattan. It took me twenty years to realize that this event was different from any other. It was my first global event experienced online—and perhaps the last national event we experienced in common, before the internet altered how our cultural memory works.

At the time, I had no sense of what that meant, or what cultural and philosophical implications it had. I registered the event as a historical fact, but could not yet consider how technology shaped my perception of it. Though our memories of historical events seem most firmly fixed in images, the last twenty years have seen enormous changes in how we see and process them. So much has happened in only the last five years—a global pandemic, mass demonstrations, political violence, the erosion of democratic norms, and more—that I am skeptical about whether any single picture sums up this inchoate time. Whereas throughout the twentieth century, the photographs of David Seymour, Henri Cartier Bresson, and Lee Miller—to name only a few—were reproduced in grand-format magazines like Life, or in daily newspapers, today we absorb the world via screenshots of fragments of brief videos, moments endlessly looped and shared as GIFs that circulate from phone to phone. Experiences of historical events that we have come to understand communally, via photographs and video footage, have been atomized by the ways we now use the internet. Logging on to personalized platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Reddit, and Instagram, we encounter content based on whom we follow and what those users have uploaded.

In Maël Renouard’s Fragments of an Infinite Memory: My Life with the Internet, translated by Peter Behrman de Sinéty, the author remarks that he now considers his childhood in the late twentieth century to be a time of relatively few images. “I have the impression,” he writes, “when I look back on it, that my...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in