Format: 160 pp., softcover; Size: 7.56 x .59 x 10.03 inches; Price: $25. Publisher: Drawn and Quarterly. Number of Kinder Surprise Eggs depicted at the grocery store checkout: nine; Number of times the events of the past overtake the reality of the present: too many to count.

Central Question: Is it possible to find the universal in the particulars of a grumpy middle-aged cartoonist’s depressing life?

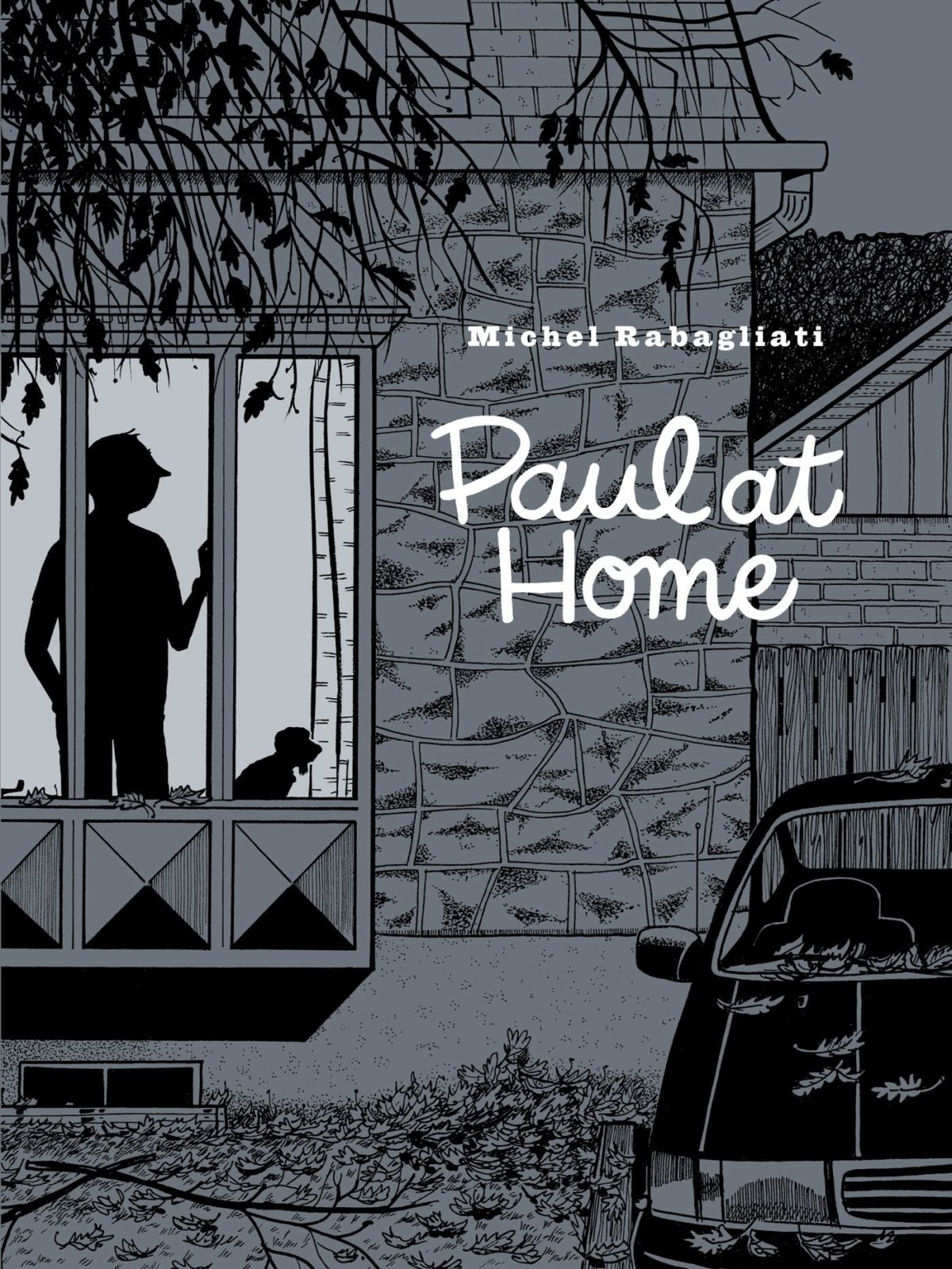

In 2017, the Canadian graphic artist Michel Rabagliati told the magazine Taddle Creek that he was at work on a new entry in the ongoing Paul series, a collection of graphic novels describing the life of a canny young Canadian not dissimilar from Rabagliati himself. This newest book would be “the most autobiographical by far and definitely the most depressing of the series!” Whether or not Paul at Home is autobiographical, it certainly trucks in the melancholy: Paul, whom Rabagliati’s dedicated readers have seen through a lifetime of adventure and self-discovery, now lives alone in a walk-up in Quebec, long past his prime as an artist and trapped in the eddying currents of late middle age. We watch as Paul visits specialists for his cracked tooth and sleep apnea, as he tries to connect with his young adult daughter, as he struggles to rekindle his elderly mother’s enthusiasm for life. But for a book that could easily become a series of complaints about loneliness, aging, and a fading career, Paul at Home is much more: it’s an exacting chronicle of the everyday, a work of big-hearted humor, and a memoir that’s as much about the potential of the future as it is about the bittersweetness of the past.

At the beginning of the book, Paul is in the grocery store searching for a single tomato for a meal he plans to cook for his mother. This experience is quasi-universal, and it was this detail that made me, a millennial at the beginning of their career, interested in learning more about this anomic boomer. The story of another life becomes immediately relatable when it focalizes around the mundane: picking a tomato, crossing the street, eating dinner. The banal, pinprick’s-width event is precisely the kind of thing that reminds us of our common humanity. The smaller the story, in other words, the larger its audience.

Paul visits a crowded bank where he imagines being detained and questioned for trying to deposit a check in U.S. dollars. Paul deals with his next-door neighbor, Antonio, who is adamant that Paul cut down the dying tree in his backyard. Paul notes with disdain that a pool maintenance store is called “Aquatic Solutions” (“‘Solutions’ is the word of the year… Ten years ago it was ‘club’ or ‘depot.’ Solutions club depot! Million-dollar name!”) Paul ruminates on the fonts of highway signs. Paul gets pissed off that everyone on the train with him is on their phones. Even in the midst of Paul’s cynicism, Rabagliati draws him wide-eyed and open-faced, and it’s this graphic friendliness that makes him more than a caricature of middle age. It’s easy to identify with Paul in these moments regardless of age or other demographic markers: the book is proof that the highs and lows of human life don’t discriminate. Paul at Home is broad and accommodating in its minutiae, big enough to contain a diverse readership. Though it may help to be a cantankerous old white male cartoonist before picking up this book, you don’t necessarily have to be to enjoy it.

As I read, I found myself not only relating to Paul but reflecting on shibboleths between generations. Paul’s daughter wants to leave Quebec and live in England, and, reading this, I remembered how I’d spent my early 20s in a state of restlessness, convinced of my parents’ ignorance and eager to break free of their influence. It’s rare for Western popular media to spend any time dwelling on the empty nest: it’s so easy for us to forget, in other words, who and what we’re leaving behind. Paul at Home was a refreshing reminder that, if we’re lucky, there are people who love us waiting for our safe returns, and that we, too, may someday become those people waiting on kids who want nothing but to get away from us. It’s easy to pretend that we’re going to be young forever, but the truth is that age comes for us all. And believe it or not, that doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing.

Paul at Home refutes the old adage that with age comes wisdom: at fifty-one, Paul appears to know as little about what he’s doing as any of us do at thirty-one or twenty-one. But it does impart an essential truth about getting older, which is that the life behind us tells a story that only gets richer as we age. Rabagliati tells the story of Paul’s mother, a woman who, despite suffering through years of depression and a marriage as unhappy as Paul’s, still managed to live a life full of many of the things she wanted: kids, cooking, and trips to the beach. In a particularly touching scene, Paul depicts his mother at the peak of her happiness, a beautiful young wife putting on makeup in preparation to see a British singer in a “big fancy theater” with Paul’s father. Later, Paul takes his mother back to the family’s old apartment, where the two remember his mother happily watching Paul and his friends play in the alleyway. The reminiscence is short-lived, but it’s a reminder of the life shared between them, the fact that transcendent beauty can be found in the everyday—which seems, incidentally, to be one of the major themes of Paul at Home.

The dead tree in Paul’s backyard becomes a motif throughout the book, increasingly brackish and rotten every time we revisit it. Toward the end, the tree has been hacked apart, and its trunk lies in pieces on the ground. In a different memoir, the tree’s death would be intended to give the reader some sense of foreboding, perhaps to underscore the idea that, as Paul’s mother’s life comes to an end, so too will Paul’s career, his relationships with his daughter and ex-wife, and then his own life as well. But Rabagliati repurposes this motif as a message of hope and renewal. Just as Paul has said goodbye to some of the major players in his life, his neighbor Antonio offers him a small cherry tree in a pot. Paul is at first skeptical—Antonio never offers him anything without demanding something in return—but when he learns that the gift comes with no strings attached, he experiences perhaps the first moment of relief and genuine happiness in the book. He plants the tree and in subsequent pages, in begins to grow. Although much of Paul’s life is behind him, his story is not over.

It may be easy to mistake Paul at Home for a book about loss, misery, and the hopelessness of middle age, but it’s sunnier than all that. In its careful attention to detail and thorough examination of the challenges and triumphs of being human, it’s a book that offers an opportunity for growth, not just for Paul but for the reader sympathetic to his situation. As a chronicle of a life, Paul at Home is a success. Unless Rabagliati writes another Paul book, we can’t know for sure what will happen to our misanthropic hero, but we can only assume that his future will be much brighter than expected.