I first met Raven Leilani—who you’ve likely heard of by now—in graduate school at NYU, where I became a staunch admirer of the poetry and short fiction of hers I’d read online. We shared only one class together, during the second of those two years; a craft seminar. Leilani was quiet in that class, though when she did speak, her insights were revelatory. It was a special thrill to receive a galley of the novel she wrote during the program, Luster, during the early months of government-imposed lockdown. At a time when my attention span felt impossibly short, my mind clouded by the dread and monotony of 2020’s “new normal,” Leilani’s startling, meticulous prose and biting observations held me rapt (and often had me laughing out loud).

The opening pages of Luster plunge us into an explicit text conversation between Edie, a twenty-three-year-old Black woman making a host of questionable life decisions, and Eric, a married white man twice her age. Edie and Eric met on a dating app, where he pointed out typos in her profile, then told her about his open marriage; she saw neither of these as red flags, instead focusing on the heady buzz of their distinct power imbalance. The ensuing pages see Edie losing her dead-end admin job, struggling to pay rent, and tumbling headfirst into a tension-charged situationship—not only with Eric, but with his wife, Rebecca, and their adopted daughter, Akila, who is also Black. This unlikely collision of worlds fuels something vital in Edie as she fumbles her way towards a life as an artist. Leilani examines the nuances of race, class, artmaking, sexuality, and relationship dynamics with a shrewd and darkly humorous eye. Hers is a bold, urgent, and irreverent voice I’d follow anywhere. We spoke over email about failure, want, rage, and writing towards ugliness.

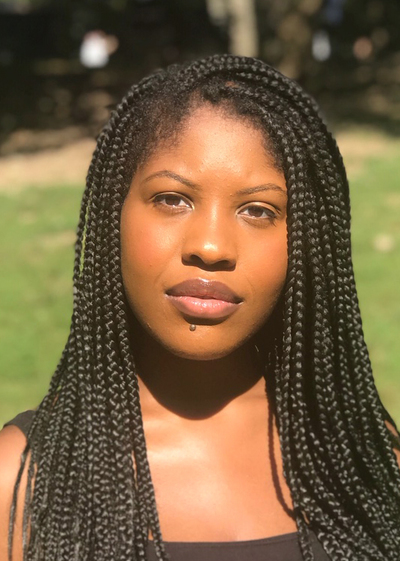

—Annabel Graham

THE BELIEVER: The conceit of an open relationship is inherently rich fodder for fiction. What I find most unique and compelling about the one you’ve rendered here is the sense that it isn’t Edie’s relationship with Eric that ends up being the most important one, or the one that changes her. Instead, those relationships she unwittingly forms with the women in his life—his wife, Rebecca, and their adopted daughter, Akila—come to the forefront. Can you talk about that choice?

RAVEN LEILANI: The relationships that are most interesting to me are relationships between women. Edie seeks intimacy and affirmation desperately, often from the men she is involved with, which I think is natural, but ultimately unfulfilling. It’s the women she encounters who treat her seriously and who challenge her in such a way where there is less room for performance, and more room is made to inhabit herself authentically, where she is more free to express her rage and joy.

BLVR: Were there any major differences between what you initially thought you wanted to explore with Luster and what materialized in the end? Did any themes or ideas emerge that surprised you?

RL: I started with the body. Ultimately that is all I need in a book—a book that is rigorous in its presentation of want, where room is made to show how absence can mutate desire and can make it an ugly thing. So I wrote toward the ugliness first, and that led me to everywhere else it crops up, in seeking intimacy, in artmaking—I was surprised by how much rage was there, in the subject matter and in me.

BLVR: Failure seems central to Edie’s experience of the world. I love the way you explore her journey towards becoming an artist in all its awkward, unglamorous chaos. What has failure meant to you, as an artist?

RL: Failure hurts, and some of it I’m sure I’ll carry around for the rest of my life, but it is everything. To be clear, I don’t want to indulge the idea that difficulty is romantic, especially if we’re talking about trying to make meaningful work when you are literally just trying to eat, but the reality of honing your craft is one that, to me, involves significant trial and error. I don’t think I started writing anything good until I accepted that rejection is par for the course. It made me less precious. It made me realize that revision is where the work gets done, that sometimes the thing you wrote sucks, and even if you throw work out, none of it is wasted if it gets you there. It freed me from the idea that writing to appease others might grant me entry, and in a way, it clarified my love, because there was no humiliation great enough to make me want to stop.

BLVR: So much is expected and assumed of Black women by our culture—there are so many unwritten rules and restrictions. You address that fact head-on here, especially in Edie’s gutting recognition of the stringent expectations placed upon her by Rebecca, who seems to want Edie to be a “certain type” of Black woman that suits her own personal needs. How did you navigate writing into that tension—and writing a character like Edie, who actively resists conforming to society’s skewed ideas of how she “should” be?

RL: I wanted to afford a Black woman the latitude to be fallible. I wanted to write against the idea that there is a particular way to comport yourself to earn the right to empathy. Black women are especially subject to this expectation, and I think to have to expertly navigate racist and sexist terrain to survive and be denied the right to a human response is to deny that person dignity. It’s a recipe for a repressed, combustible person. I’ve been there, and I’m still unlearning that reflexive curation as we speak, so it was a relief to write a Black woman who leads with her id. It was a relief to write toward her want and rage without apology, which is, unfortunately, what some people might find unlikeable.

BLVR: In the early pages of the novel, Edie fantasizes about Eric punching her in the face; later, he does enact violence upon her, with her consent. Can you talk about Edie’s relationship to violence, and what it means for her to choose it?

RL: The question of why she wants this is predicated on the assumption that she shouldn’t want it, but on all fronts, I tried to steer clear of the idea of should. Or I tried to write non-judgmentally, and allow a black woman, who is subject to the mandate of performance in the public realm, to assert her agency privately and ask for what she wants without pathologizing her choices. I think I could honestly say too, that I’m not entirely sure what it means—that I wrote a black woman who is being ground to dust in all areas of her life and has decided to take a more active role in her annihilation and this attempt to seize control of an inevitable thing ripples through her sexual leanings. I’m really open to all the readings on this. The conversations I’ve had around this part of the book have been really surprising and wonderful.

BLVR: On the prose level, your precision is astounding—the word “sharp” has been used in almost every review I’ve read of Luster, and it’s apt—your sentences cut in a visceral way. What is your writing process like? Do you revise heavily as you go, or does that come later?

RL: I revise really heavily as I go, to the point where I can’t continue if something feels wrong. It makes me a much slower writer, and that’s frustrating, but I do truly want any reader that comes to my work to feel how much I care, how much joy is there.

BLVR: You’re also a painter. For you, how do the two mediums of writing and painting inform one another? What has each taught you about the other?

RL: Not to bring the mood down and return to failure again, but painting was the medium that taught me how to fail and how to know when to quit. Unlike writing, with painting, the failure I felt there was excruciating. Maybe because when I saw the extent of my limits, my love didn’t outweigh the work I knew I would have to do. So I have had a much slower journey with that, and as you can see that subject keeps creeping into my written work. On how the actual craft translates, with both mediums I had to have a come-to-Jesus moment about the unsexy components of making art. I couldn’t just jump in and take liberties. There needed to be an understanding of the fundamentals, of what makes a composition or story work. For painting, anatomy, perspective, etc; for writing, the crafty decisions that happen in between the emotional thrust. The math that comes before the color. For a long time my bedrock was flimsy, and until I addressed that, so was everything I built on top of it.

BLVR: Were there any pieces of art—books, films, paintings—that felt particularly inspiring or helpful to you while writing Luster?

RL: Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior, Audre Lorde’s The Erotic As Power, Katie Kitamura’s A Separation, Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, Edward Hopper’s Ground Swell, Batman: The Animated Series, Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, Numa Perrier’s Jezebel, Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale, Morgan Parker’s There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Samantha Irby’s We Are Never Meeting in Real Life, François Ozon’s Swimming Pool.

BLVR: Do you have any rituals, writing or otherwise?

RL: I clean if I’m procrastinating, but otherwise, I sit in bed with my computer and write until I can’t anymore. I always write with music, usually something scary and percussive. I can’t write around other people, so I’m always writing at home, usually in bed.