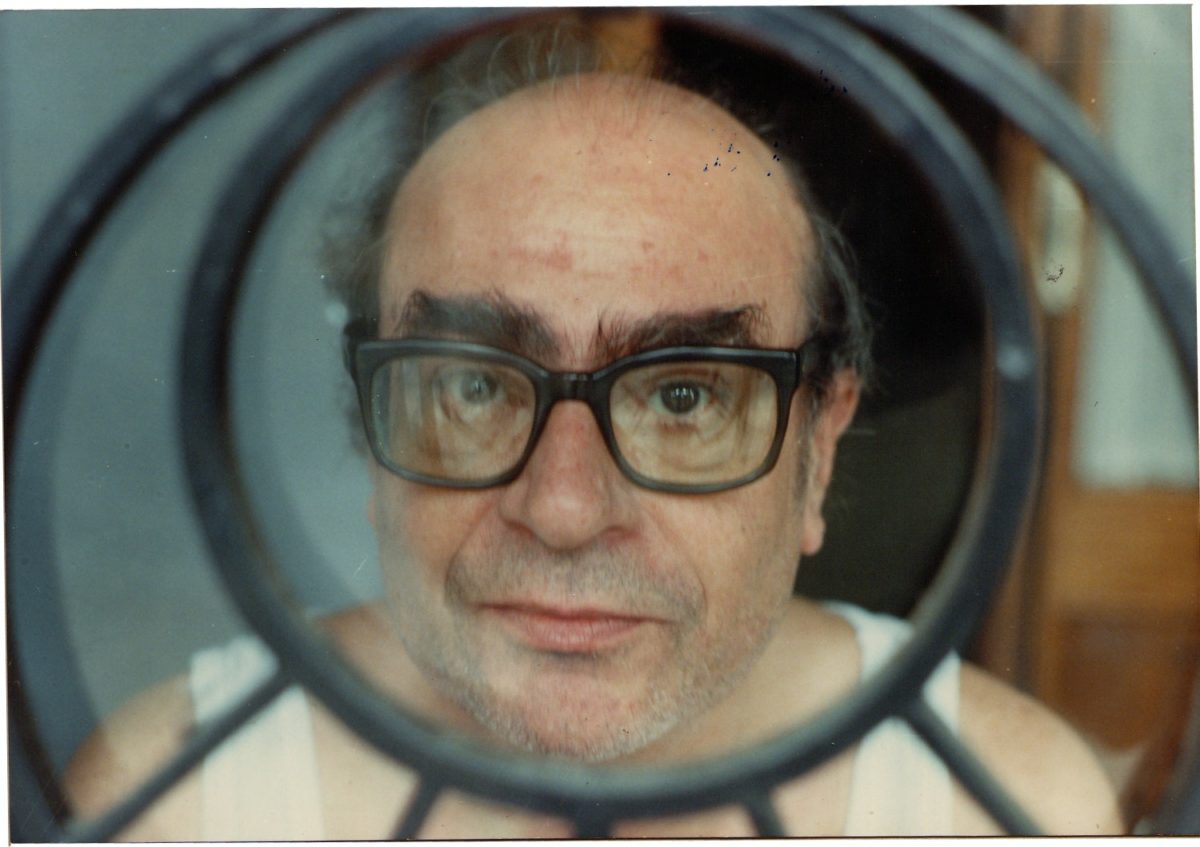

Mario Levrero—bookseller, cartoonist, crossword setter, leader of creative writing workshops, tango fanatic, and amateur mystic—was also the author of some of the strangest and most astonishing works in the Latin American literary canon.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in