Enter Ghost

October 1st, 2021 | Issue one hundred thirty-seven

Spiritualism’s theories of supernatural communication, the afterlife as media, and how technological hauntings live on in film

1.

There is a kind of cinematic prophecy, a big-screen dreamworld that eerily anticipates the real. An event erupts into our attention—a natural disaster, a political movement, a war, a celebrity scandal—and we feel we’ve seen it already in a film, with worse writing and better-looking actors. How this happens is anyone’s guess. These are prophecies without a prophet, the result of no supernatural power. They are just a strange by-product of Hollywood narratives engineered to fill seats. How many times did movie terrorists attack Manhattan before 9/11? How many viral outbreaks did we endure before the coronavirus pandemic? As governments scrambled to contain the current virus, their actions recalled the plots of pandemic films like Contagion (2011)and Outbreak (1995). The US government may not have been prepared for a global catastrophe, but Hollywood had already prepped our imaginations, giving the events of 2020, not for the first or last time, an unwanted familiarity.

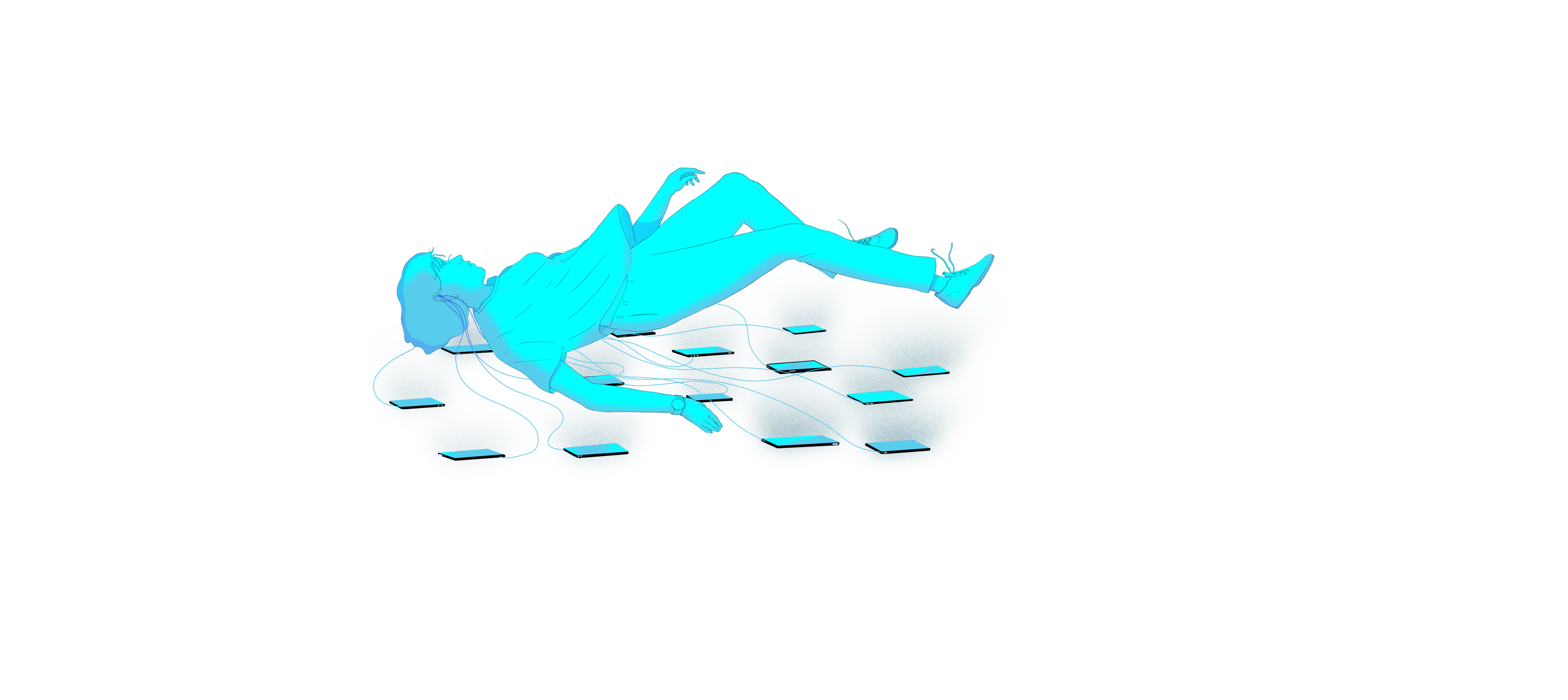

So we went inside, where screens colonized what was left of our time. In only a few weeks, friends, family, coworkers, political candidates, and celebrities were reduced to grids of faces in glitchy chiaroscuro. Online video conferencing had an unexpected leveling effect, in which celebrity-packed theater productions and family birthdays were nearly indistinguishable in their format and awkwardness. People we once saw in person every day now appeared on our computer screens, competing with emails and Netflix. Digitized, encoded, flattened, and backlit, other people became digital ghosts, neither fully present nor completely unreal. These digital ghosts proliferated, in homes and outside of them—ghosts that were no longer just weird or eerie but also melancholic and bored. The melancholy was paradoxical: one missed one’s friends and family, even though one could see them all the time. See them, but not be with them. Presence, rarefied, was now reduced to a field of pixels.

For two decades, horror movie producers have been grinding out films in which ghosts travel over digital connections, terrorizing teenagers in chat rooms and inconveniently intruding into video calls. Sporting tech-titles like Unfriended (2014), Friend Request (2016), and Cam (2018), these films are released, it seems, as frequently as app upgrades. They feature formulaic plots in which an online suicide or disappearance or rumor is not what it appears to be. Ghosts, demons—even Satan himself—are lurking in the network. The purer examples of the genre are shot entirely on webcams (or professional cameras imitating webcams) and use grid formats identical to those of a video conferencing app. It’s all very silly, with the expected exploitational admixture of hot-button issues (teen suicide, cyberbullying) and freak-out entertainment (The ghost is right behind you!).

The haunted internet genre began with the upmarket template Pulse (2001), directed by Japan’s horror master Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Pulse is the Rosemary’s Baby (1968) of internet horror, a one-of-a-kind masterpiece that triggered countless rip-offs, spin-offs, remakes, and sequels, none of which re-create the movie’s singular poetry. Pulse is an enlarging spiral of terror whose starting point is a hacker’s suicide and whose outer curves contain a Tokyo emptied of people. In between is a plot involving an afterlife that has run out of room for the dead. With nowhere else to go, ghosts are downloading themselves into present-day Tokyo via a website featuring videos of wraithlike people in darkened homes. After a character discovers the website, ghosts begin appearing, the character commits suicide, and their apartment is declared “forbidden.” Meanwhile, other characters receive phone calls from the dead, and images of darkened rooms proliferate across more computer screens. Room by room, almost the whole of Tokyo disappears into the afterlife. Pulse then shifts genres, becoming a post-apocalyptic film, with the few unlucky survivors wandering through a depopulated Tokyo, eventually trying to escape by boat to South America.

Pulse doesn’t make any sense, but it doesn’t have to. The film elevates mood over logic, free association over cause-and-effect, somehow giving lines like “Instead, they’ll try to make people immortal by quietly trapping them in their own loneliness” an explanatory power. Pulse conceptualizes the internet as a necrotic space that warehouses ghosts, but also as a finite space, prone to overflowing into ours. Pulse is a film whose every frame is infected with a loneliness that spreads like a virus. Andwith that loneliness comes the lonely act of watching: people watching people on screens watching people on screens, with the film’s audience, of course, the last link in the chain. In one instance, a character looks at a screen on which they can see themselves, from behind, looking at that same screen, opening up a mise en abyme of solitary looking.

Today, it’s hard not to find Kurosawa’s film premonitory. People isolating themselves indoors, their apartments filled with clutter. Solitary, unwitnessed deaths. Long hours spent in front of computer screens looking at other lonely people. Television reports of dead strangers, each absolutely ordinary in their smiling headshot. Depopulated cities, quieted by a viral outbreak, the remaining pedestrians transformed into the last people on earth.

2.

Every communication network addresses an absence: someone has left the room, the house, the country, this life, and we want them back. Our networks will only ever bring back a piece of that person—a voice, an image—but sometimes a piece is enough. It is not hard to see how a technology that traffics in these pieces might be confused with the ghostly, and how in our imaginations, our communication networks might be confused with the afterlife. Ghosts have been infesting communication networks long before Kurosawa’s film, starting with the very first telegraph transmissions in America. The invention of the electric telegraph was synchronous with the rise of spiritualism in America. Both came out of a desire for communication—one with the living, the other with the dead—and both were optimistic gambles on the country’s future.

Spiritualism—having emerged from the same wild cluster of New York counties that gave the nation Mormonism, Adventism, and Millerism—was a socially progressive movement. Many spiritualists were also feminists and abolitionists. Spiritualism drew its members mostly from the white middle and upper classes, educated men and women who were disillusioned with Protestantism’s conservatism and patriarchy. They were determined to abolish slavery and give women the right to vote. (The house in Rochester that hosted some of the earliest séances was also a stop on the Underground Railroad.) Some Black political radicals gravitated toward the movement, including Sojourner Truth, who lived for a decade in Harmonia, a utopian spiritualist community. Spiritualism was one of the few women-led movements in nineteenth-century America, and more of its writers, artists, and mediums—the last, famous, highly paid, and sought after—were female than male. Historian Ann Braude has shown that spiritualism’s stages and séance tables were among the few places women could have a voice in America at the time. (Though, paradoxically, not always with their own voices, as trance mediums were often said to be channeling the voices of dead men.)

At the time, death was everywhere: children died often and young; slavery destroyed countless Black lives and would lead to civil war; and families were lost to what would become preventable diseases. First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln organized séances in the Red Room of the White House, some of which were attended by the president. Mrs. Lincoln was not alone: by 1890, forty-five thousand Americans were formally associated with a spiritualist society, though the number of believers was probably much higher.

Meanwhile, these same Americans were sending telegrams and learning to make phone calls, two technologies that, even to the educated, appeared to border on the supernatural. For the first time, the world was communicating with itself across great distances, nearly instantaneously, and spiritualism was right there to ride the wire. The “spiritual telegraph” became the movement’s prime technological metaphor, though it was frequently literalized when some mediums offered their services for intercontinental communications. Scholar Anthony Enns writes of the medium James V. Mansfield, a.k.a. “the spirit-postmaster,” whose arm would spasm during séances as if charged by “an electro-magnetic circuit, enabling [the spirits] to approach and influence the nerve-center of his motor system.” This “human telegraph” would then tap out the letters with his finger, in a manner that was “business-like, orderly, and straight.”

Spiritualism lacked a foundational book, and it had no real theology. The movement was many things, but it was also a theory of communication—a wild, pseudoscientific one, but a theory all the same. Its message was simple: there was an afterlife, and we could speak with it. By the turn of the century, spiritualism was a clearinghouse of supernatural communication technologies: table rappings, talking boards, automatic writing, spirit slates, trances, even fanciful machines. Some of these technologies, such as automatic writing, were far older than the United States itself, while others were as new as the telephone. Spiritualist publications freely sampled from the current scientific discourses on electricity and chemistry, and much of the movement’s theorizing was done by scientists operating on the margins of their professions. Spiritualism designated its members as “investigators” rather than believers, encouraging a kind of light skepticism. Rarely, an investigator ranked among America’s new scientific elite, as in the case of Thomas Watson, an assistant to Alexander Graham Bell.

Every Sunday in 1875, Watson convened a “spirit circle” with his childhood friend George Phillips. With Phillips leading, the table they sat around tipped and rapped in response to their questions—the efforts of a “disembodied spirit,” according to Watson. Soon John Raymond, the future mayor of Salem, Massachusetts, joined them, and the three men graduated from rappings to ventriloquizing the dead. In one session, Raymond started convulsing and, perhaps in preparation for his political career, declaimed a thirty-minute speech from a dead orator.

For Watson, his parallel activities—the invention of the telephone and the séances—produced a paradoxical confusion between electricity and the spirit world. As he would later write of the séances: “I was now working with that occult force, electricity, and here was a possible chance to make some discoveries. I felt sure spirits could not scare an electrician, and they might be of use to him in his work.” Notice the reversal: electricity was the true occult science, one that might explain the spirits away while also assisting the electrician in his scientific work.

Late at night, Watson spent hours “listening to the many strange noises in the telephone and speculating as to their cause.” He heard snaps, grating sounds, a twirling like the chirping of a bird. He was the first to hear these sounds, and with scientific theories of electrical interference yet to arise, he speculated that they came from another planet. As Avital Ronell writes in The Telephone Book: Technology, Schizophrenia, Electric Speech, Watson “opened an altogether original channel of receptivity… [he was] the first convinced person actually to listen to noise.”

By “noise,” Ronell means electrical noise, static. Long before forward-thinking electronic-music composers made static a subject of serious listening, Thomas Watson was concentrating his ears on it, hearing what he thought might be interplanetary voices. Voices, music, soundscapes, the ghostly—the next century would search for signals where there were none, sometimes as a prank, more often in search of meaning.

The telephone would become the next century’s great interrupter. Globally, the phone network fragmented attention. Dinners, quiet nights at home, intimate conversations, and reading time would rarely be free from intrusion by distant voices. Intimacy was rewired, near and far scrambled. Voices from the past, ex-lovers, bill collectors, family members looking for money—the phone suddenly produced anyone and anything we’d tried to forget. And why not the dead? Starting in the nineteenth century and running well into the twentieth, one could read of haunted phones and phone-switching stations, of calls from dead relatives and murdered lovers. In 1878, The New York Sun reported that calls coming from a telephone installed in a cemetery’s office were waking a Catholic bookseller in the middle of the night. When it was found that no one had accessed the cemetery phone, and that the bell was mechanically operated, the cemetery owner locked and secured the room holding the phone. The calls continued, and everyone involved suspected a spirit was at work. On September 24, 1907, the Alexandria Gazette reported that a new phone exchange had been built in Wellesley, Massachusetts, because phone operators believed the old one was haunted. (A night operator had been found dead there two years earlier.) In the January 1933 issue of The Telephone and Telegraph Journal, a subscriber complained that after a repairman fixed their supposedly haunted phone, a rumor spread in the town that the house itself was haunted.

It took longer for the haunted telephone to cross from news into fiction, with Elliott O’Donnell’s 1934 story “The Haunted Telephone” being one of the earliest known examples. It tells of a country doctor who, after answering a telephone call, finds that his identity becomes blurred with that of his disappeared predecessor. The story is also one of the earliest in which telecommunication causes confusion between the past and present. The plot of Nigel Kneale’s now-lost 1954 BBC radio play You Must Listen sounds very much like the urban legends circulating in the margins of the press: After a phone is installed in a solicitor’s office, the staff hears a

woman’s sexual monologue on the line. (No voice ever responds.) The voice, they learn, is that of a mistress whose lover is refusing to leave his wife. She commits suicide and her voice haunts the line. Mario Bava’s three-part film Black Sabbath (1963) features an episode in which the voice of a supposedly dead ex-boyfriend haunts a woman’s phone. Around the same time, Richard Matheson adapted his short story “Long Distance Call” for a 1964 Twilight Zone episode (“Night Call”), in which a lonely elderly woman receives calls from her deceased husband. In the TV version, before she hears her husband’s voice, the woman hears static on the other end of the line.

3.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s 1965 short story “Dial F for Frankenstein,” the phone network does not transmit the dead but becomes its own living being. Clarke’s story is set in 1975, then the near future, on a day when all the world’s phones ring in unison as a kind of planetary prank call. Everyone who answers the phone hears not a voice, not a recording, but “a sound, which to many seemed like the roaring of the sea; to others, like the vibrations of harp strings in the wind.” But it is the sea sound that predominates, the rush one hears when listening to a conch shell, that “secret sound of childhood.”

In London, at a café across from the Post Office Research Station, a group of engineers debate what caused the call. Was it a power surge? Or was it the recent satellite launch, intended to connect all the world’s telephone networks? The group’s amateur sci-fi author has an idea: Since Alexander Graham Bell, he says, the telephone system has been thought of as a giant brain, with each switch acting as a neuron. What if, after the satellite launch, the switches in the phone network reached a critical mass of connectivity? And what if, like a newborn, the network is now awake and looking for food?

As they talk, the lights flicker. A jet flies unusually low over the building. Later, a fire alarm rings. After that, a bank receipt shows an employee with almost one billion pounds in the bank. One of the engineers opens a newspaper, and although the layout has the normal columns of type and photographs, the text is scrambled into “a sea of gibberish.” What is happening? The engineers guess that the new “supermind” is like a newborn baby: it’s looking for food—electricity—while extending its reach and causing havoc. A BBC report confirms that across the globe there have been industrial failures, the launch of guided missiles, airplane groundings, the shutdown of stock exchanges. The communications satellites have cut themselves off from central control—there is no way of shutting them down. Then the BBC signal goes silent, leaving the engineers to consider whether humanity itself has reached its end.

When the story was published, none of Clarke’s readers would have expected a fire alarm to connect to the same system that lays out a newspaper. There wasn’t yet an internet, and telecommunication networks were a specialized topic. Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, later claimed he read Clarke’s story as a child and that it had inspired the Web’s creation. Though, considering that the story ends in an apocalypse, it’s hard to see why anyone might want to emulate it.

Predating Pulse by a few decades, “Dial F for Frankenstein” imagines a network that expands beyond its confines, laying waste to its makers. There is no ghost—for the first time, it is the network itself that is alive. Unable to speak, it prank-calls the world. And when the world answers, there is no spirit on the other end of the line ready to announce its arrival. What’s calling is the line itself. Without a voice, without a soul.

The German media theorist Friedrich Kittler was a collector of these kinds of calls, calls that said nothing, came from nowhere, sounded like the ocean or like a conch shell’s roar. In his book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, he writes about a dream of Franz Kafka’s in which the writer finds two telephone receivers, or Hörmuschel (“listening shells”), on the parapet of a bridge. Kafka picks up both receivers and asks for news of someone named Pontus (the name of an ancient sea god). On the other end of the line he hears “a sad, mighty, wordless song and the roar of the sea. Although well aware that it was impossible for human voices to penetrate these sounds, I didn’t give in, and didn’t go away.”

Kittler traces that static-like sea sound through early modern literature, from Kafka to a little-known 1907 short story by Maurice Renard. In it, a composer and his friend, grief-stricken by the loss of several of their dinner club members, alternate between listening to a recording of their dead friends and putting their ear to a seashell. One asks: “What if this ear-shaped snail stored the sounds it heard at some critical moment—the agony of mollusks, maybe? And what if the rosy lips of its shell were to pass it on like a graphophone?”

Later, Kittler discusses another lost short story, this one by Salomo Friedlaender, a.k.a. Mynona: “Goethe Speaks into the Phonograph.” The story’s conceit is that sound waves and voices never fade: “These [air] vibrations encounter obstacles and are reflected, resulting in a to and fro which becomes weaker in the passage of time but which does not actually cease.” Build the correct machine, the story’s professor protagonist believes, and you can snatch the sounds back from the past—in a way, resurrecting anyone you wish. His first test subject? The father of German literature, Goethe himself.

After a visit to the writer’s tomb, the professor hooks up a microphone and phonograph to an anatomically correct re-creation of Goethe’s larynx. He brings the contraption to the writer’s study, placing the larynx on a tripod not far from where Goethe’s mouth might have been. There, the professor and his audience listen to the writer speak with poet Johann Peter Eckermann about Newton’s theory of color.

Kittler stresses that with the invention of voice recording, one could, for the first time, capture not just the sign of a thing but its physical residue, emanating waves frozen in wax. (The same could be said for photography, which captures the light bounced off bodies.) This fact changed how we thought about our media, its powers as well as its possibilities. Kittler does not seem very interested in spiritualism, though he would have found it offered a playground of strange media ideas. In particular, he could have discovered a cluster of theories that proposed that no image or sound is ever lost. Like in our own digital age of cloud storage and Time Machine backups, this is a dream of a past in which everything is recoverable. The dead come back if you know where to look—all you need is the right sensitivity or ingenious machine. An artificial larynx and a phonograph, maybe, or a supernatural talent allowing a person to miraculously repossess the past.

4.

Annie Denton Cridge claimed to be just such a person. Little is known about Cridge today. What survives comes from her spiritualist publication, The Vanguard; her stream-of-consciousness books, including My Soul’s Thraldom and Its Deliverance; and the few traces researchers have found in archives. She was born in England in 1825. In the 1840s, along with her brother, the geologist William Denton, she immigrated to the United States. By age twenty-three, she was a writer, a memoirist, and a socialist. She was also a grieving mother who had seen her infant child’s spirit rise from its body to be greeted by its deceased grandparents. From that moment, Cridge was an ardent spiritualist and claimed the ability to see ghosts.

According to her brother, Cridge was also a “psychometrist,” a person who, by laying hands on an object, can glean information about the object’s past. The term was coined by Joseph Rodes Buchanan, a physician and her brother’s employer. In a journal he published, Buchanan wrote that psychometry, from the Greek for “soul measuring,” was a gift available to certain people, who, just by touching an object, could learn something about its effects (if it was a medicine) or its previous owners (if it was a personal item). In experiments he describes at exhaustive length, Buchanan claims to have shown that individuals with “acute sensibility” could read the contents of a sealed letter by holding it to their head (thus anticipating Johnny Carson’s Carnac the Magnificent by more than one hundred years). Others, when presented with a written autograph, could produce a “mental daguerreotype” of the autograph’s owner. Buchanan’s crackpot science could, he claimed, revolutionize human communication, medicine, archeology, and history. It might even lead, Buchanan wrote in a fit of the manic optimism that colors much of his writing, to the reconstruction of all of human creation.

Buchanan does not mention Annie Cridge in his 1885 Manual of Psychometry: The Dawn of a New Civilization, but her brother devotes space to her in his own 1863 book, Nature’s Secrets: Or, Psychometric Researches. For several chapters, Annie and her sister-in-law, Elizabeth, are William Denton’s star subjects. When presented with a host of rocks and fossils, first Annie and then Elizabeth narrates the objects’ origins with novelistic vividness. After Annie is presented with a piece of limestone from near the Missouri River, she sees a hill by a river. When Elizabeth is presented with tufa from near Vesuvius, she has a vision of a violent eruption.

Psychometry’s trigger is touch, but vision is its real operative sense. The women are presented as seers. “I see…” begins most of the testimonies. Though the telegraph might have been the medium’s preferred metaphorical machine, for the psychometer, the world-governing metaphor was the daguerreotype. Like most of the pseudo-scientific writing on spiritualism, William’s book begins with a reasonable premise: we retain memories that we unconsciously repress and bring back involuntarily at a later point. Denton then expands his theories to argue that objects retain unconscious impressions of what takes place around them, like a daguerreotype. Here he makes the leap: “In the world around us radiant forces are passing from all objects to all objects in their vicinity, and during every moment of the day and night are daguerreotyping the appearances of each upon the other.” Enter Annie and Elizabeth, whose brains are “sufficiently sensitive to perceive [these radiant forces] when [their brains are] brought into proximity to the objects on which they are impressed.”

In Denton’s writings, history—the deep history of geology, or the more recent history of one’s life—operates like a photograph, or, more accurately, a film strip. What is of interest in Denton’s writings is not their scientific accuracy but his anticipation, almost by accident, of the cinematic apparatus. The first film cameras would be invented at the close of the century, but here is an idea that the world retains not just a single image of itself but a succession of images. When Cridge and Elizabeth narrate their visions, they are static—they are describing paintings, really—but on occasion their language suggests motion, as when Vesuvian lava flows into a boiling ocean. What Denton describes is a kind of cinema avant la lettre, history as a phantasmagoria, “the history of its time passed before the gaze of the seer.” Far before Orwell and the Stasi and the National Security Agency, the world becomes a giant recording device, aimed in all directions, with total information awareness.

Nigel Kneale, the writer of the lost telephone radio play mentioned above, used these ideas in his cult TV show The Stone Tape, a bizarre 1972 BBC Christmas special in which a ghost is projected from the stone wall of an ancient house. (A ghost of a woman appears, falling from the same staircase over and over again, as if looped on a tape. The “tape,” a group of scientists learn, is the stone itself.) Denton’s ideas took a century to find their ideal home: on a TV show (among the first to be shot entirely on video) about ghosts who are trapped like images caught on video tape. This is the afterlife as media, as a space in which one’s image is predestined to play in infinite reruns.

Likewise, spiritualism’s afterlife is found in the movies, where it is doomed to repeat, perhaps forever, the same gestures and plotlines. In narrative films like The Uninvited (1944), The Changeling (1980), and Hereditary (2018),one can watch the familiar séances and psychometric visions; child ghosts who return to grieving mothers; and chalkboards writing their own messages. On occasion, one gets a complex evocation of the movement, as in Olivier Assayas’s Personal Shopper (2016). But more usually Hollywood depoliticizes spiritualism, stigmatizing its ideas and transforming its mediums into eccentric crones. Christianized, the lesson of Hollywood spiritualism is that one shouldn’t play with Ouija boards and that Satan lurks in every basement.

There is, though, in films like Pulse, a residue of the movement’s weird theories of mass communication, however dark this vision may have turned. The happy miracles of the “spiritual telegraph” have become the nightmares of the haunted internet genre. As scholar Jeffrey Sconce has written, spiritualism’s optimism concerning communication technologies was greatly tempered, if not completely reversed, during the twentieth century. By midcentury, the dead were no longer up for a telephonic chat: they pestered, sabotaged, interrupted, and terrorized. In a word, they haunted. Now, with cloud storage and 24-7 connectivity, the past, it seems, is always recoverable. But it is impossible for us to believe that cell phones and Zoom calls will deliver this past free from worry and fear. The problem is not how to bring back the past, but how the dead can, once and for all, stay that way.