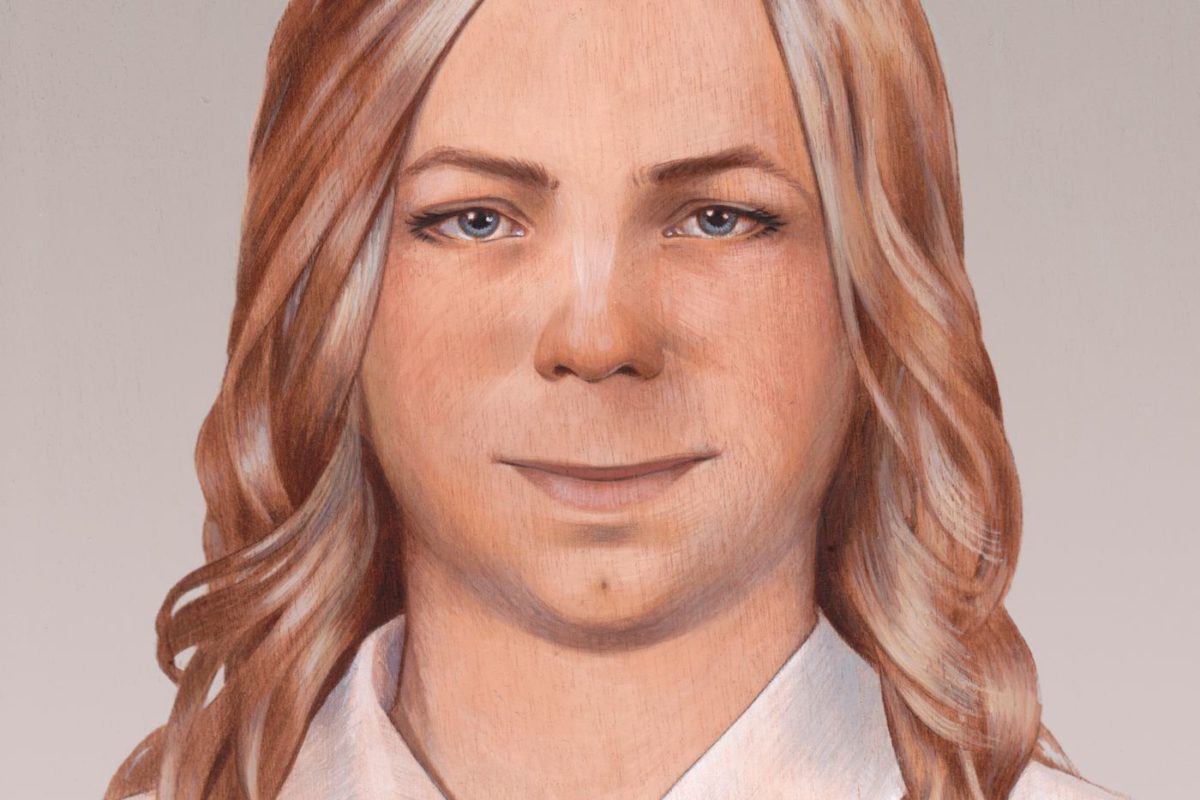

Writer and critic Hatty Nestor spent her childhood between the council estates of Essex and the desert landscapes of New Mexico. This experience of existing between two places, and her exposure to how criminalized people are portrayed in each of them, informs her first book Ethical Portraits: In Search of Representational Justice, published by Zero Books earlier this year. Initially started as an oral history project, the book is structured through a series of interviews with artists making portraits of incarcerated, wanted or missing people today, in prisons, courtrooms, zones of solitary confinement, and spaces with heightened law enforcement or other modes of surveillance. She speaks to courtroom artists known for their slapdash sketches of celebrities, painter Alicia Neal who was commissioned by the Chelsea Manning Support Network to create a portrait of Manning while in solitary confinement, forensic modellers and contemporary artist-activists, all the while questioning: “How can we represent those who are not seen?”

I speak to Hatty on a bright and early Thursday morning over Zoom, the white wall of her South London flat behind her. Her conversation style is similar to her writing: careful, thorough and questioning. Any suggestion of her writerly authority is immediately refused. Nestor says she never saw Ethical Portraits as a ‘big non-fiction book’, but something more open-ended, in which writing is used to ‘agitate.’ Carceral Capitalism by Jackie Wang (who writes the introduction to Ethical Portraits) is a cited influence, as is The Journalist and The Murderer by Janet Malcolm.

Malcolm’s influence is evident in Nestor’s conversation with courtroom artist Priscilla Coleman. “I realised that ethical conundrum of portraying another person was as relevant to me, as an interviewer, as it was to her, as a sketch artist: both are practices of necessarily subjective witnessing,” Nestor writes, emphasizing the complicated power struggle between artist and sitter, interviewer and subject, even outside the criminal justice system. Coleman is a good subject for Nestor; a Texan artist who moved her work to the UK when courtroom sketches were banned from US courts and who has drawn portraits of Amy Winehouse, Rolf Harris and Heather Mills pouring water over the head of Paul McCartney’s lawyer. Coleman describes her job in cold, workmanlike terms, which is essentially a media job, with tough deadlines. In Ethical Portraits, Nestor considers these courtroom sketches—usually of high-profile and celebrity cases and so familiar from appearing on television and in newspapers for most of our lives that they are almost invisible, an archaic and harmless oddity—in a new and critical light. Due to Nestor’s thinking, we see them afresh, and as part of the same subjection and control of the criminalized subject as mugshots, e-fits, pro-fit systems, or disingenuous artist projects. “I have come to understand an ‘ethical portrait’ to be a depiction of someone which holds political weight, is integral and empathetic, which challenges marginalization through a visual image,” Nestor writes, with a sense of longing. Ultimately, she believes that aesthetic is justice possible.

—Natasha Jane Stallard

THE BELIEVER: Let’s start with the title: Ethical Portraits. It’s an interesting choice to frame a book about the visual representation of prisoners. In the book’s introduction you ask, “Can art create an accurate, ethical visual representation in instances where prisoners are otherwise dehumanised?” You examine portraits of prisoners which aren’t ethical, ones which are trying to pass as ethical, and others that may be successful. So the title suggests a sort of longing or an unresolved ideal. Is that how you saw it?

HATTY NESTOR: Definitely. Both of those terms are rooted in definitions from the art historical and ethical sphere. Portraits were historically always of people in wealthy positions or positions of prestige. In portraits there’s always that power dynamic at work. And obviously the term ethics is so broad. There’s a lot of writing about the ethics of faces, for example. When I was looking at drawn and painted portraits in the justice system, I thought I couldn’t write about questions of portraying without considering ethics too. Hopefully the book isn’t didactic. It’s more thinking about the ways in which portraits can be created in that system which may further the invisibility of people who are already rendered invisible. And the instances where that’s been subverted, like the Chelsea Manning case. But longing is an interesting idea, because it links into the idea of utopia, or the ability to imagine otherwise, like dreaming. That’s what I took from Jackie Wang’s book Carceral Capitalism—the psychic power of imagining otherwise is so fundamental for people who are physically constrained, which relates to representation too.

BLVR: Images like mug shots and courtroom sketches are so ingrained in our culture that the book also serves as a reminder to reconsider them as an act of portraiture. As you say, there is always a power dynamic at play between who is taking the portrait and who is being portrayed. Before it’s even seen. The courtroom sketch artists who you interviewed talk about their job in a very workmanlike way. Essentially it’s a media job with extremely tight deadlines. They sit in court all day and once they’re out they do the sketch in ten minutes.

HN: Courtroom sketches are really interesting. They are images that the justice system commissions or requires to give visual testimony and documentation to people who are on trial. I interviewed the courtroom sketch artist Priscilla Coleman who said sometimes she changes small things to depict someone in a way she thinks they might want to be depicted, like removing a double chin. We are conditioned to think the justice system is doing something neutral but there is a lot of subjectivity at play. Courtroom artists have to sell sketches to media outlets, so there’s also the question of capital, and what will make profit. It’s an act of art in the name of capital. When actually it’s people on trial. Courtroom sketchers only depict famous people and high profile cases because that’s what the public wants to see, and it is sensationalized.

BLVR: One of the first images which come up when you do an image search for “ethical portrait” is of Tyrone Lamont Allen, whose mugshot was photoshopped by the Portland Police in 2009 to remove his facial tattoos. You don’t focus on mug shots in the book but you describe them as “the protocol of the justice systems implementation of discipline. They’re the least merciful representation of prisoners, which demand their subjects to act as if they were already corpses, staring into the camera with morose expressions wearing the uniform orange jumpsuits.” When you spoke to Alicia Neal about her commissioned portrait of Chelsea Manning, she makes a comment about the black and white selfie of Chelsea Manning which was then used by the press and “circulated like a mug shot.”

HN: Mugshots are solely for documentation. They’re how you can be identified in prison. If you go to a prison website you might be able to see a mug shot alongside a prisoner’s number. What became really interesting to me is the idea that you can be identified by an image, when that image is so far from how you would like to be identified or how you see yourself. There is much more to be said about policing online and offline, and the circulation of a portraits, or a selfie, without permission from the person. Chelsea Manning’s leaked selfie is a great example of this. At the time the only public images of Chelsea Manning were in uniform and the selfie which had been sent as a call for help to Paul Adkins, her supervisor at the time, which was then leaked. The transgender trolling that happened after that in the news was really, really cruel. The selfie was circulated in a manner which goes against what a mug shot is supposed to do in terms of identification.

BLVR: It’s a self-portrait.

HN: Yes and that’s something which can be deeply personal. It was this kind of trolling that led the Chelsea Manning Support Network to carry out the commissioned portrait by Alicia Neal. Her comment always stayed with me actually, she said the mugshot was “very damaging to Manning’s image.” Because are we actually talking about a mug shot here? Or are we talking about a violation of someone’s call for help that just happened to be through a visual image? I think it’s interesting that she said it was circulated like a mug shot because most people’s mug shots aren’t always hyper visible or circulated.

Acrylic on birch plywood and digital

8”x10”

BLVR: In the interview Alicia Neal says she wanted to portray her realistically and not like a fantasy character. She doesn’t use some of her usual modes of painting. She gives her a Mona Lisa smile. It’s a really beautiful portrait and they never met in person. You describe the portrait as arriving from a position of “shared hope.”

HN: I think Alicia Neal was very sensitive when creating her portrait. Chelsea Manning was having a really rough time in solitary confinement. And Alicia Neal was in this weird position where she had been commissioned by the support network because Chelsea Manning had picked her from a selection of artists. Alicia Neal portrays herself as someone that’s quite politically neutral, who actually created this deeply political image.

BLVR: You also make a comment about Chelsea Manning’s access to a support network and being able to commission an artist like Alicia Neal.

HN: That felt like a very difficult thing for me to say but there is also a hierarchy within accessibility. Chelsea Manning is someone who has horrifically suffered at the hands of the legal system and the military. She exposed violence through leaking documents, which most people wouldn’t do because it would cause them so much personal anguish and harm. She faced a very long sentence for whistleblowing. Because it was a high profile case there were lots of people who wanted to get involved, and also give further representation to her through different means, whether that was legal support or personal. She’s so adored by the left and seen as a hero, and now has a great deal of visibility. Nonetheless there’s obviously thousands of inmates who will be in horrific situations and will not have that access. So we also have to look at these hierarchies in terms of which cases we know about and how they’re represented.

BLVR: What also becomes apparent in Ethical Portraits is how the general public’s imagination of courtrooms and incarceration comes from high profile cases or the entertainment industry, because that is the dominant mode of visual representation. You mention yourself watching true crime.

HN: True crime is really interesting because it makes us reflect on what attracts us to extreme, high profile cases. This in itself mimics the hierarchies of representation, of visibility through sensationalization in the media. Are we drawn to true crime because it reminds us of something we’re not? Or is it just another kind of drama with crime and violence contained within it?

BLVR: You say how the drama lies in whether or not the person is going to lose their agency.

HN: Absolutely. The Ted Bundy case was interesting for that reason. He was a very privileged white man who had studied law, so he could perform his own defense. Lots of women turned up to the trial to see him, even though they could have been his victims. There’s something in that about voyeurism. It’s not surprising that true crime has taken the role it has in popular culture. The high profile cases which end up as true crime are a very particular, sensationalized representation, whereas the majority of prisoners usually don’t receive any representation publicly. It does reflect the underlying sentiment of what people are interested in. True crime asks a different question of the viewer as a participant and what this genre evokes in us.

BLVR: You refer to Janet Malcom’s analysis of the power dynamic between the journalist and their subject in The Journalist and The Murderer and her famous line “the journalist is always morally indefensible.” I find that interesting for two reasons: one, how you included an interview with an artist in each section of the book, while questioning how the artist had visually represented their subject, which makes a very astute point about how the portrait artist and journalist are dealing with similar issues in the ethics of representation. And two, because Malcolm’s book takes on a true crime case, while also critiquing the genre and self-critiquing her role within it.

HN: What Janet Malcolm does really successfully is how she polarizes her own role alongside her subjects. She talks about being morally indefensible, that journalists and writers might be telling a story the subject doesn’t want to be told, which is a form of representation itself. But there is this kind of power dynamic which Janet Malcolm talks about, where interviewing is always an act of portrayal as well. Each chapter in the book has an interview, so I’m creating a portrait of each person through writing. For me, it’s the idea that writing can agitate. I really think about that as a writer—how can I raise awareness without necessarily reconfiguring people’s behavior or telling them what they should or shouldn’t do. Those are some of the moralistic questions that were most challenging.

BLVR: At this point it would be good to discuss your personal position in writing about the experience of incarceration. You grew up in a working class family in Essex and the book includes your experiences of living in the Mid and South West of the US between 2017 and 2018.

HN: Institutionalization is something I experienced firsthand through a family member. The way in which someone can be disciplined, their behavior constrained and access to news and education restricted. This form of disciplined experience you know, hit me like a truck. It was so strange, dissociative and odd. You don’t realize as a kid how it affects you, yet later your relationship to a system is already conditioned.

BLVR: Okay, that’s interesting.

HN: I know. It just felt like I was witnessing it. I don’t know if a lot of people who experience institutionalization when they’re young have this ethical judgment. But for me, I don’t think I did. The experience in this country is slightly different to the US. But the way in which we deal with people in the justice system or how we define a crime is what I’m passionate about and care deeply about, because obviously it’s embedded in so many questions of class alongside other political and ethical issues.

BLVR: In the introduction of Ethical Portraits you discuss why you took the decision to interview the artists rather than the incarcerated. Can you tell us more about that.

HN: Speaking to artists was interesting to me because they can seem like gatekeepers, and at times have a great degree of power over representation. They have an element of control and they are sometimes mediating the inside from the outside. This ties into public perception, especially courtroom sketch artists. Artists actually enact what interviewers do and they are given a lot of implied power in terms of testimony. An artist who is doing this kind of portrait may come to it from very different places, particularly in terms of ethics, such as the Captured project by artists and activists Jeff Greenspan and Andrew Tinder. There is a really complex relationship between an artist’s intent and then what actually prevails in terms of agency.

BLVR: You criticize the Captured project for its prescriptive element.

HN: I found the Captured project quite difficult for several reasons. The project is more about the art and what the founders of the project are trying to do, which is to make a point about how rich people “white collar crime” don’t get incarcerated for their crimes. While those lower down the economic ladder do. We already know that. If that’s the only point, does the project need to use the free labour of artists in prison? I question the method by which they found the artists for the project, which was through eBay. If an artist in prison is selling their artwork online, there must be someone helping them or a support network at work. I don’t think there was a big enough excuse for the project to rely on eBay, especially as there is Jmail now, which allows you to send out mass emails to a lot of prisoners at once. Although, a lot of the prisoners I spoke to did find the project really humanizing. But I did find something quite problematic in terms of the portrait style and its ethical sentiment.

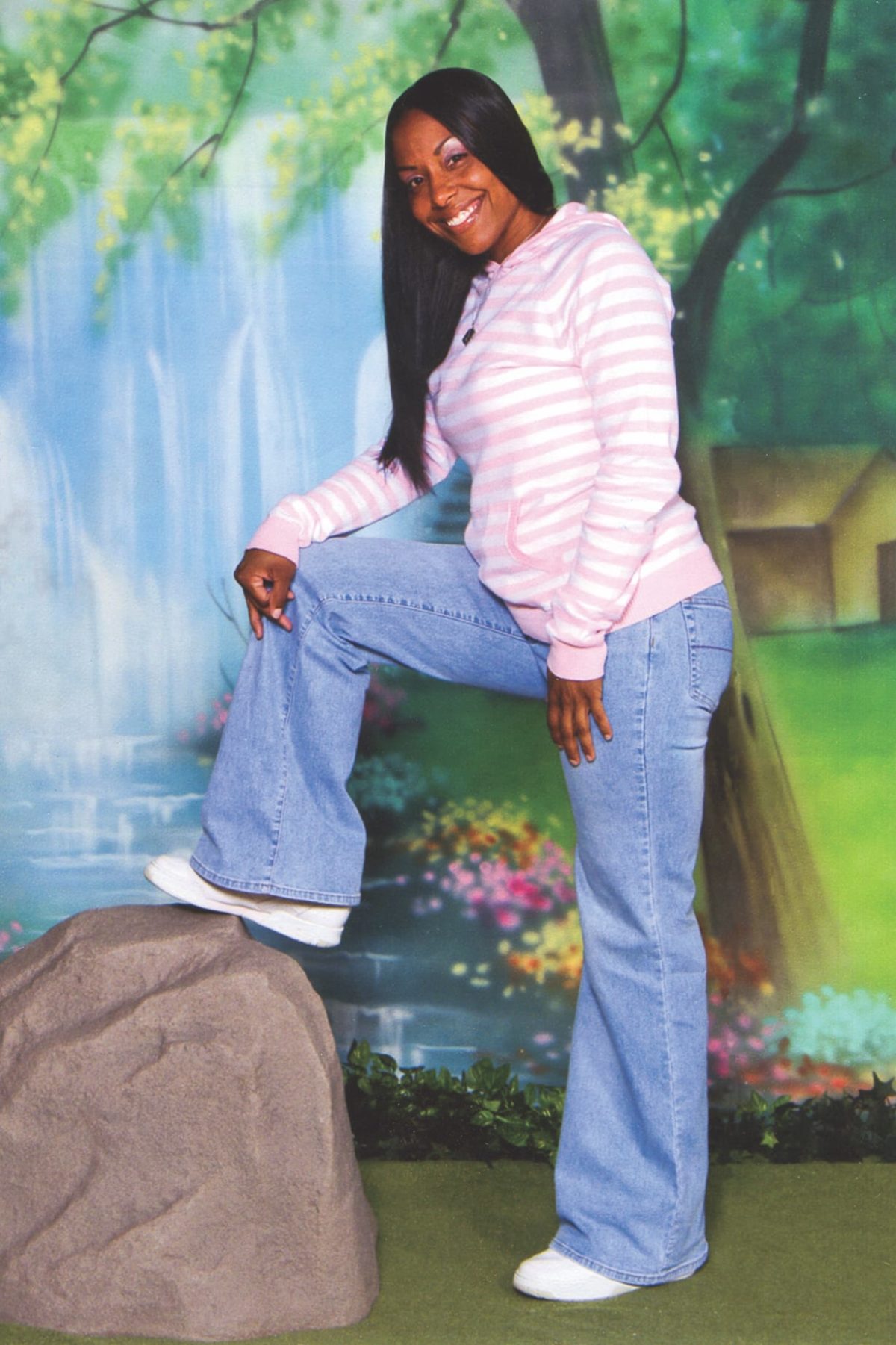

BLVR: In the portraits of high profile cases we’ve mentioned there is no choice but to engage with the media landscape. In the Captured project they chose to create images for media consumption. In contrast, you praise artist Alyse Emdur’s project Prison Landscapes for its approach. When you put those projects side by side, it is easy to see how the mural images aren’t there to make an easily digestible point, which gives them a more intimate value.

HN: Absolutely. A choice was made to not include information about prisoners in the book, so you don’t know their names or numbers. Outside of the book’s context, the person could be anyone standing in front of a mural anywhere. That kind of anonymity is enabling. The murals have a sense of utopia and hope, and they were often painted by prisoners. Emdur, who collected the portraits, was not instructing a particular artistic image.

BLVR: What becomes very clear in your book is how an “ethical portrait” isn’t just the final image but the process in which it was produced. Particularly when you are working on portraits with people who are very limited in the images they can create. You also mention how in the Prison Landscapes series, the inside and outside collapse, rendering an instance in which difference can be imagined.

HN: Yes, Emdur isn’t commissioning the portraits, she’s collecting them. She did this mostly through letters and she also had her brother incarcerated. So there’s an acknowledgement of the privacy that’s happened. The murals in prison aren’t produced for the public and there is a lot of choice within them. And the portraits in front of murals are usually taken to be sent to friends or families. There’s something very private about them.

BLVR: The mural scenes feature landscapes of waterfalls, beaches and sunsets or iconic city scenes and monuments. They’re never fantastical or sci-fi scenes. In an interview, Emdur says what she gathered from her correspondence about the murals, is that “realism is like gold in prison.”

HN: The realism tied into a wider societal idea about how we see nature or public monuments—what does it mean to be photographed next to the Statue of Liberty? Again, it is also important to think about which inmates get to paint murals or even have face to face visitation rooms. Obviously that’s not a possibility in high security units. But the prison landscapes are important because they give access to the idea of dreaming and being sometimes different to how prison defines, and represents you.

BLVR: You are very careful to pose questions about each of the portraits that you examine in Ethical Portraits and to leave things open-ended. But you do propose that visual art does have an important position in terms of representation.

HN: The portraits I investigate have very different ethical questions tied to them. Some of the portraits in the book do provide something that is not “legal” justice, but justice in terms of representation. Particularly in this era of surveillance, image tampering and forensic modeling, we have to consider the role of these images for their criminalizing and liberatory effects.