“When you photograph a moment, you’re photographing the death of that moment.”

There’s a scene in the Oscar-winning 1978 film Ordinary People in which an affluent but deeply dysfunctional family attempts to take a few simple snapshots during a holiday gathering. We all know the ritual, but here you can feel the tension ratchet up into the red zone as they try to decide who’s going to take the picture, who’s going to pose with whom, and where everyone’s going to stand. It goes on for a very long time until the stress is nearly unbearable. The scene crashes to an end when Timothy Hutton, as the troubled teenaged son, finally snaps, “Just take the goddamn picture!”

I was thinking of that scene as I flipped through Michael Lesy’s most brilliantly compelling, fascinating, and surprising work to date, Snapshots: 1971–1977 (Blast Books).

With the publication of his groundbreaking and wildly influential Wisconsin Death Trip in 1973, Lesy carved out not only a unique literary niche for himself, but launched a new form of journalistic social criticism. What he did, at heart, was propose a new way of understanding history by trying to understand what archival photographs might reveal about a time, a place and a people—not just the people in the photos, but the people who took the photos as well.

In the decades that followed, Lesy, now Emeritus Professor of Literary Journalism at Hampshire College, scoured increasingly large photo archives to produce Murder City, about Prohibition-era gangland violence in Chicago, Looking Backward, a collection of century-old stereographic images taken around the world, Repast, in which he used early twentieth century menus and archival restaurant photos to examine the evolution of culinary culture, and several sprawling collections that looked at the photographic records of America at assorted pivotal moments in our collective history.

In his latest, however, Lesy didn’t find his subject matter in a carefully curated, meticulously catalogued archive stored in a climate-controlled vault in some university library. No, the photos reproduced in Snapshots were all things he liberated from the dumpsters behind a photo-processing plant in San Francisco (and later from a Cleveland drugstore’s trash).

The processing machines at these photo plants worked so fast that often they’d spit out three or four copies of a picture before the operator had time to react, and those duplicates ended up in the garbage. As it happens, Lesy had a friend with a motorcycle who worked at the time as a courier, delivering rolls of film from drugstores around San Francisco to the processing plant, and delivering finished packets of photos from the processing plant back to the drugstores. Being a familiar face around the plant, this allowed him and Lesy easy access to the treasure trove of discarded snapshots in the dumpsters out back.

While sitting in those dumpsters, these may have been nothing but simple, banal, discarded personal snapshots—weddings, birthday parties, people posing with new cars or the 12-point buck they just shot—but to see them through Lesy’s eyes they take on an unexpected beauty and profundity. Given the time frame, yes, a cursory glance may leave us chuckling at the bell bottoms, the unlikely perms, and all that wood paneling, but there’s much more going on here, most of it perhaps far more familiar than we’d care to believe. Amid a nation and world rocked by Vietnam, the Tate/LaBianca murders, the Attica uprising, Watergate, and an endless string of radical bombings from coast to coast, the ordinary people in these simple snapshots—sometimes blurry, occasionally off-center—say more about the state of America at that moment than any collection of banner headlines.

“Seen through the eyes of an outsider like me,” Lesy notes in his introduction, “the snapshots looked in four directions at once: out at the subject, back at the photographer, inward at their assumptions and beliefs, and then out, beyond them, at the world in which they thought they lived.”

—Jim Knipfel

THE BELIEVER: I guess the obvious opening question has to be, what prompted you to start dumpster diving behind a photo processing plant?

MICHAEL LESY: First of all, it was a wealth of images that were just trashed. The idea that this stuff is just coming out like water out of a firehose, and just getting thrown away. It’s an industrial machine for images. I mean, images of families. That’s what snapshots are. There’s this big company that does this stuff, and it serves thousands of customers. I was thinking, this is a way to understand large groups of people. It’s just sitting there.

BLVR: This was a couple years before Wisconsin Death Trip. Were you already working with the photo archive at the Wisconsin Historical Society?

ML: It was around the same time. They’re different kinds of archives. Some of them are inside historical societies, and some of them are in garbage cans. The only thing they have in common is, who’s doing the looking and what questions are they asking?

BLVR: You mention in the introduction that you were probably salvaging about seven thousand photos a week.

ML: Or more, yeah. Eventually I asked my friend, who’s still alive, thank god, and that was his answer. It’s not precise, but it’s close enough.

BLVR: As you were going through them, was there anything in particular you were looking for? Any specific characteristic that would determine if you kept a picture or threw it away?

ML: I was just looking for stuff that made me stop. For example, towards the end of the book there’s a photograph taken, probably by a road crew. It was a road kill that got run over and then painted over. You stop and think about that. What it took to do that. What kind of mind would do that? “So let’s think this problem through.” That was so extraordinary that my friend and I kept that tacked to the wall for weeks and weeks and weeks. There were things like that that were just startling. Then there were things that were just deeply affecting. And then there was stuff that answered the question I didn’t know I was asking. That is, who are these people? These Americans—what do they do? How do they carry on? I looked at the book this morning, and I think what I was always going for were the eyes. The eyes and the expression. I was looking for hope, or anger, or sorrow, or whatever it was. Because you think of snapshots as fairly coarse, fairly crude common denominators as opposed to, I dunno, a studio portrait by a great portrait photographer. But as I looked, they revealed all sorts of emotions the subjects were experiencing at the time the pictures were taken. You don’t have to be a fine art photographer or have your work up on the walls of a museum to make photographs that reveal people’s souls. So I was looking for the eyes. I didn’t purposely go looking for the eyes, looking for people’s expressions, but they were so affecting.

BLVR: I think that’s especially true in pictures of people waiting to have their picture taken—that is, pictures taken a few seconds before or after the official photo, when the subjects are in place, but not quite ready yet.

ML: Sure.

BLVR: There’s a particularly striking example in the book, two photos taken a few seconds apart of a newlywed couple at a wedding party posed to cut the cake.

ML: Yeah, yeah, yeah. There’s a lot of those.

BLVR: In the official photo, they’re smiling and looking at the camera. In the next, they’re looking away from one another, their faces have fallen. It’s very sad, but that’s where you see the truth of the situation.

ML: What that amounts to, and what photos really can do—and I don’t think anything until then really did—was it gave you these interstitial moments. You have the official moment. There’s the official battlefield painting, or the official salon painting of the Great Man. Then outside of those archetypal moments there’s the way people actually are. What photographs did, which no one really anticipated, was it gave us a way to look at ordinary life in ways nobody expected. Because we weren’t up to the task either.

BLVR: Going through the book, there are two notes I jotted down. One was that, even accidentally, some of these photos are so beautifully composed. I think of the centerpiece, the picture of the little girl and the jumprope.

ML: There are no accidents, man.

BLVR: Also in here there are a lot of photos that have a real Diane Arbus quality to them.

ML: Oh yeah, but it’s not accidental. Part has to do with the editing, let’s face it, the initial pass through this pile of stuff. But it’s not all like that.

BLVR: No, of course not. I’m just thinking of a few scattered examples.

ML: Yeah, so first of all there’s the editing, and what the editing sees and doesn’t see. That picture of the girl with the jumprope is very, very beautiful. And all the Arbus stuff is very beautiful. But Arbus had also seen people. She made things that became art objects, but before she made art objects, she just walked through the world in a way that was disaffected, or lonely, or angry, or hopeful, or however she walked through the world. And she noticed things, like we all do.

BLVR: A lot of these photos were clearly taken to commemorate something in these people’s lives—weddings, birthdays, christenings. But in many cases, we have no idea what, no idea why someone was there with a camera taking pictures.

ML: Oh, come on, man, if you’re there in a motel room taking pictures of your girlfriend while she’s waiting to have sex with you…

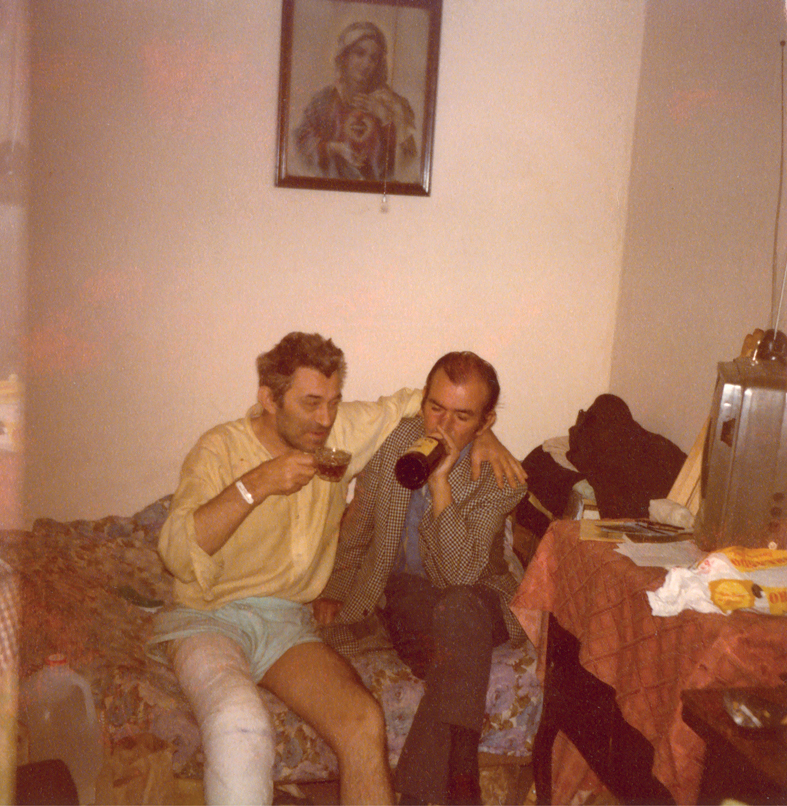

BLVR: Or the two guys drinking in a seedy room, one of them with a broken leg. I love those guys.

ML: That was Blast Books’ Laura Lindgren’s doing. And not just Laura. There was a guy, one of my best students—he’s in the acknowledgments—his name is Zach Phillips. At a certain point I was clearing out my office. I was at the end of my teaching life, and I gave him a lot of stuff. And god bless him, he found those pictures in that pile. I hadn’t noticed them, or if I had I hadn’t even thought of them as keepers. But Zach found them when he was a twenty-something guy looking back at ancient history. And he turned Laura onto those. So it was that process of discovery by intimate strangers that got those pictures into the book.

BLVR: Speaking of things we may not initially notice, there’s a short series of photos in the book—I think these are from Cleveland—in which we see a Black woman in red slippers reading the paper, then dancing in her living room with family—maybe her sons and grandkids—then dancing with a very confident-looking man. And Laura Lindgren mentioned that it was only just before going to press that she noticed that the man, in the last picture, is carrying a gun in a holster at his waistband. All these things you can look at a million times and simply not see.

ML: That’s right. We see things that we don’t know we see. There’s a picture on the cover of a book I did when I was at W. W. Norton called Long Time Coming, which is photos taken by the Farm Security Administration. It’s a picture shot over the shoulder of a bystander looking at a July Fourth parade. So that’s the cover. In the foreground is a picture of a lady in a 1940s housedress. I wanted that picture, and I wanted it on the cover, but because I wanted it on the cover I had to look at it even harder, and that’s when I saw she’s missing one leg. And I thought to myself, that’s really what this whole country was all about. It has to do with not seeing stuff that you do see, and then realizing that you saw it, and deciding not to forget it. You’re three people at certain stages of the looking. That’s really how to look at snapshots and look at the pictures in the book. There are some people who I think are very alive and alert, and probably can see a lot at one glance. But most of us need these remedial devices to really see what’s there.

BLVR: There are so many examples of that in the book. In one there are four girls lined up in front of a house, and it takes a second or third glance to realize one of them has a leg brace and a prosthetic shoe. You think nothing of it until you notice that.

ML: And then you notice her girlfriends are all styling their legs differently. I ran that past Laura, and she was skeptical. I still think it was a response to that girl’s disability that the others, who were her girlfriends, are posing purposefully, showing their legs in different model styles. Reading photographs for the backstory…

BLVR: That’s exactly what I wanted to bring up. We’re approaching all these intimate photos as outsiders, and we can’t help but to invent back stories and relationships between the people in the pictures.

ML: When you sit down—well, no longer, but when you used to sit down—with family albums, no matter how well executed they were, whether they were just scrapbooks or whatever, however haphazardly or shabbily made, when you go through them, you tell different stories to different kids or different friends each time you go through it. There are a whole bunch of back stories we tell ourselves for each snapshot. Then you turn them into stories that you tell strangers or friends, and those are different too. That’s the whole process of the stories that are provoked by the images.

BLVR: When my wife and I were going through the book, we were coming up with all sorts of crazy stories.

ML: Oh yeah, oh yeah. I remember sitting down with people in Cleveland and asking them about themselves and their families, using the photo albums they had to get them to start talking. What would always happen in these interviews was that there would be one photo that kind of cracked them open. You could almost hear the crack. And then all these stories started coming. They became a different kind of storyteller. This photo had provoked memories and thoughts and feelings that they had kept to themselves. The photo made them talk because they were relaxed and they were open to the past, to memory. After that, all the stories they told as we went through the photo album became more fulsome than they had been otherwise. It’s not only a good interview technique, it’s a good psychological technique for talking to people who are depressed or guarded or whatever. If you’re patient and persistent, people will begin to tell you things about themselves and other people they wouldn’t have spoken aloud without the stimulus.

BLVR: Taking snapshots used to be such a familiar, complex social ritual. You filled up a few rolls of film, brought them to the drugstore, dropped them off, and about a week later picked up an envelope with the finished photos. They were tangible things you could hold and flip through. At home you arranged them in albums, rearranged them, wrote captions, stored them on the bookshelf, and, like you said, showed them to people who stopped by. It was a very social activity.

ML: Yes. And now there’s Facebook, which is a different kind of social activity. The thing about Facebook is that it’s full of different kinds of lies, in the same way that snapshots were always full of lies. But they’re different kinds of lies because Facebook has its own implicit editorial boundaries. Now they’re explicit, in terms of race or gender or whatever. You can’t say certain things. But before that tightened up, anything goes. This is what you’re supposed to put on Facebook: happy moments, good moments, cats… People just implicitly seem to obey the norms that Facebook presented. “Everyone’s doing this, so I guess I’ll do it too.” So there is that kind of difference, because photo albums aren’t that kind of public. Really public. So what we’re getting with these images is not exactly what we’d be getting with Facebook. Years ago when there was this thing called Flickr—

BLVR: Sure, I remember that.

ML: So there was this guy who was the director of the Library of Congress, and he was pretty hip for an archivist and historian. He directed the library to sample one week, maybe two weeks of the Flickr feed, which is now stored somewhere in the bowels, the memory, of the Library of Congress. That’s a way in, too, especially if you look at the stuff as a kind of historian from Mars. He can see at one glance everything the earthlings are doing. All this stuff, all this visual information, if you know how to look—if you’re visually literate, which most historians aren’t—reveals so much.

BLVR: You mention in the introduction all the violence and all the chaos around the country at the time.

ML: Still.

BLVR: Yet you look at these pictures, and you don’t see Attica, or the My Lai massacre, or the Tate-LaBianca murders reflected in them—at least not in any obvious way—but it’s still a much more honest portrait of America at that moment.

ML: Yeah. Look, you know this, I know this, everyone who’s progressive and hip knows it. What the corporations do is give us a headache and then they sell us the aspirin. That’s what they do. They associate their products with happy family life, or at least happy ordinary life. People conform to what’s at least supposed to be happy—“it’s a snapshot, smile.” The only exception may be that African-American marriage where there’s a sign on the wall that reads, “Black and Proud.” Other than that there’s not much broadcast on political issues. They’re just there.

BLVR: There is a series of photos that closes the book taken around the periphery of what appears to be a military funeral. That could be a movie right there.

ML: Wait a second—that’s not a funeral.

BLVR: That’s not a funeral?

ML: No! It’s Memorial Day.

BLVR: Oh, Jesus. I’m an idiot. I guess that’s what happens when you grab a few clues and make up your own backstory.

ML: There are pictures in the book from a VA hospital, there’s Veteran’s Day and Memorial Day. A Boy Scout shaking hands with this absolute greaseball mayor.

BLVR: Someone made the point, and it might’ve been Laura, that these images are utterly alien and utterly familiar at the same time.

ML: Absolutely. All the time.

BLVR: Once you get past all the early seventies trappings—the fashion and the home decor—you see that then, as now, when you get right down to it America’s all about guns and cars.

ML: Yeah, you’re right. But let’s go back to the military funeral for a second. There’s something to be said for accurate information. Although you can project whatever you’re inclined to project, the cost of foreign wars, whatever, but there are other things going on in that set of photos, as I read them and edited them and saw them in sequence. It had nothing to do with the death of a single person, but the wages of sin and of war and of military adventurism. And of cruelty and of guns and of all that shit. That’s all in those pictures, and a military funeral, too, can be in those pictures, but it’s not. It can be, depending on where your mind’s at and how it travels. How it travels, how it strays, the dance that comes of the thoughts that those images provoke. But it’s very important to have accurate information before you start improvising. I think that’s really the challenge of making photo books. As an editor, you’ve done all that improvisation yourself, and then you say, Okay, so now how can I keep the viewer inside these bounds without them knowing I’m keeping them inside these bounds? How can I give them the illusion that they’re free to free-associate? I know very well from my own meditations on the images what those free associations might be, then carefully, in a sneaky way, limit them. So I think there’s something to be said about how I edit.

BLVR: Given that these were found photos and not taken from a carefully catalogued archive, did that change your approach to the material when it came to putting a book together?

ML: Sure. I always thought they were a potential archive. I always understood that what I was doing was looking at them with the eyes of a historian. But, you know, if you’re really alive and alert, you realize the present is going to be gone and dead in a millisecond and will be subject to being archived without you even thinking it will be. You know, “This is what the crowd looked like lining the street in Dallas.” And they didn’t even know Kennedy was about to get his head blown off, right? You don’t know the present, unless you’ve been looking at the past so long that it becomes, in your mind as a researcher, the present. Let me put that a different way. You look at the past as a historian, and you look at it for so often and so often and so often that the thought occurs to you, “These poor dead fuckers thought they were living in the present.” But they’re really not. They’re dead and buried. I think it’s very important to live that way, whether you’re an archivist or not. Just to realize it’s all gonna be over very quickly without you realizing it. You’re capable of not seeing anything, even though you think you are, even though you pride yourself on your alertness. Walking around with a sense of sadness and regret in the present because you know it’s gonna vanish? Because it is vanishing? That’s what’s inside of a lot of photographs. A lot of studio photographs.

BLVR: I remember reading somewhere that when you photograph a moment, you’re photographing the death of that moment.

ML: Yes, that’s exactly what we do, and that’s why I love photographs.

BLVR: In a related thought, given the photos in the book are fifty years old, and a number of the people in these pictures are relatively young, was there any concern along the way that once it comes out, someone might pick up the book and see themselves?

ML: Oh, all the time. I mean, I used to travel with these as slides. I traveled with these slides for twenty years at the invitation of colleges and associations of various kinds. I would sometimes show these instead of the slides I’d made for whatever the new book was. I was always, always waiting for someone to stand up when the lights came back on and say, “That’s my Aunt Mildred—the one with her ass in the air in front of the Christmas tree.” I was always waiting for that, because it happens. But it hasn’t happened to me. I made a book called Murder City, about Chicago. Anyway, there’s a picture on the cover, out of focus, of a crowd on the front steps of a church. I don’t know if they’re actually bringing the coffin down or not. But there are two guys who really, really look criminal. Now, people in Chicago are extremely interested in Chicago. And I got two or three letters from people who would say things like, “That’s my uncle, and he was mixed up with the Capones…” These letters would go on and on about what a rotten guy he was, how tough he was, what a murderer he was. And they were fuckin’ proud. I wasn’t anticipating that people would recognize their dead relatives in that out-of-focus funeral photograph. But I’ve been waiting for it to happen, because it happens, and I just betcha it’s gonna happen again.

BLVR: I have some friends who were in San Francisco at that time, were taking a lot of pictures, and were using several of these photo processing plants, so every time we turned the page, we were expecting to see one of them.

ML: Oh, yeah—why not? I was living with these pictures and showing them on occasion, thinking on them and dwelling on them and preserving them carefully from one different place we lived to another.

BLVR: If I may, how big is this archive right now?

ML: I honestly don’t know. I had one set of pictures that I always lived with, both the slides and the snapshots, which I kept in one of those metal index card boxes, the kind with the hinged top. And I labeled that one a long time ago, and the label was “Love in America.” I kept that box near me, either where I worked or where I slept, for years and years and years, as if it was a treasure. When I was cleaning my office out and giving things away to my students and staff, I think there must’ve been probably several hundred images, which I was keeping in a file cabinet inside double Ziplock bags. I don’t think that was good for them, because they bent. I kept those, and then I kept all the slides and the alternates of the stuff Laura and I were using for the book. Over a period of fifty years, there were probably four hundred images. Over that fifty years, I thought I possessed the secrets of American life, and it was my job to keep them safe and pass them on. I really thought of it as an archive, the way archivists think of the things that are in their charge. You take the long view.