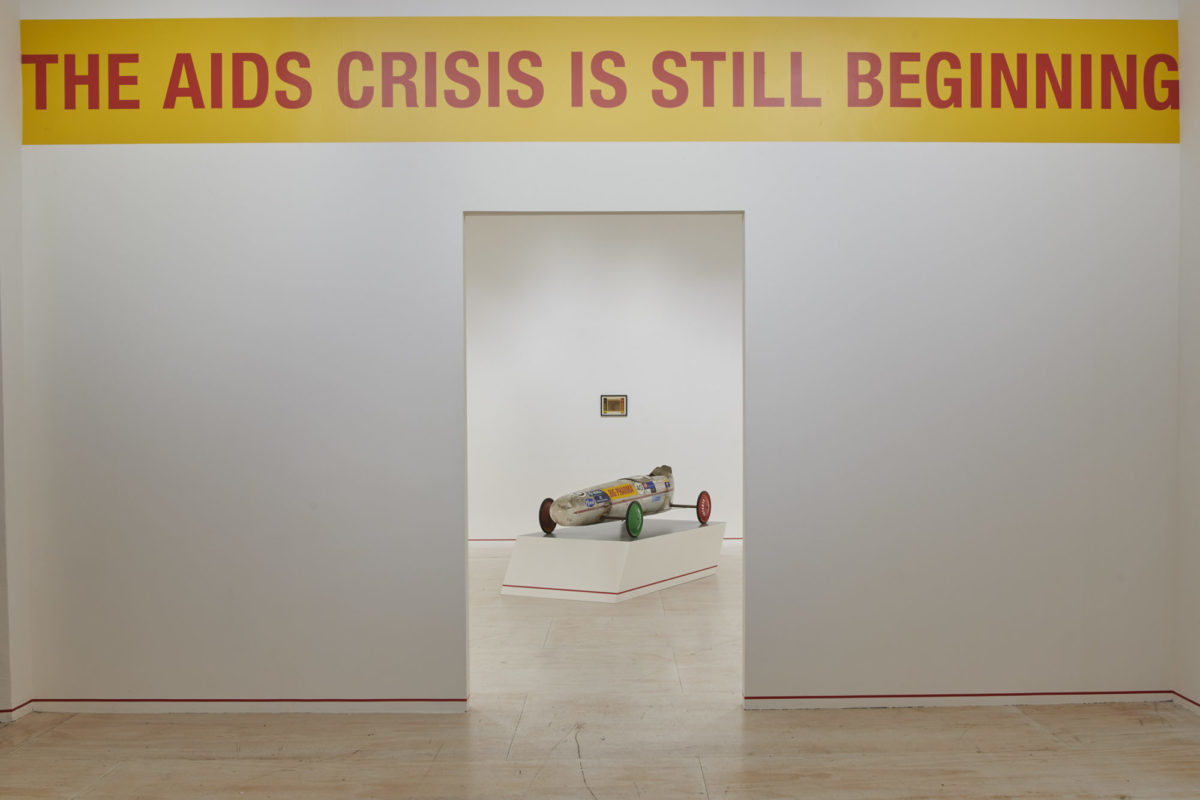

I went to Gregg Bordowitz’s show I Wanna Be Well looking for answers. I can’t recommend this as a way to approach an exhibition, and I can’t say I was totally conscious of it when I arrived. I am not conscious of everything now. My brain holds on to information only briefly. I ascribe this to my own chronic illness, pandemic burnout, my family and friends’ ongoing and acute illnesses, planning for another school year while just beginning to understand the traumas of teaching through the last, fatigue as I readjust to social life, and more, and more.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in