What’s Not in a Name?

January 12th, 2022

If Emma Woo Louie’s car hadn’t been out for repairs, she wouldn’t have met Cyrano. When the young driver from China told the 95-year-old Palo Altoan his name, he had her attention immediately. As in, de Bergerac? He had read the play and taken a liking to it, he explained. He hadn’t met any other Cyranos before.

This sort of naming origin story isn’t new to Louie; indeed, for years, collecting them was a singular obsession. Before a trip, she’d call up the local cemetery wherever the family was headed and ask if any people of Chinese descent were buried there. Given how diverse, personal, arbitrary, and informal names and their origins are, they’re hard to study. So for Louie, gravestones were remarkably informative, containing records of hard-to-access information: A person’s full name in its original Chinese characters, the English spelling they used, and their place of birth, which gave her a clue as to what dialect they spoke. “My family thought I was crazy,” she tells me.

As for many people in the small but passionate world of name study, Louie’s interest was born from a social irritant. The spelling of her last name caused people confusion: People would ask if her husband was white, or point out that 雷 should have been transliterated as Lui or Lei. “I wanted to explain to my kids how they came by the surname Louie,” she says. Both her father and father-in-law migrated to the United States in 1884. Before there were spelling norms for Chinese names, she tells me, new arrivals tended to write their names according to how they sounded.

In 1998, the independent researcher published Chinese American Names: Tradition and Transition, a fascinating piece of research about heritage, bureaucracy, and cultural confusion. Among its many stories are ones like Cyrano’s, who, Louie speculates, was following the Chinese tendency to choose unique names, rather than popular names or the names of existing people, like family members or famous figures. Thus came Bendrew, Dragona, Kenjohn, and a woman who emigrated from Taiwan and chose for her American name, Mirage.

The name exists as a gate between the private and public. It makes the ineffable self, well, nameable. It sits at the boundary of time, the product of a gestation that could have started nine months before you were born, or decades before, or generations earlier. Like an inheritance, a name in so many ways has nothing to do with us, is a privilege we did nothing to earn, and presents a legal and social burden should we wish to shed it. The emotional and cultural baggage of a name starts out being carried by someone else, by people who’ve maybe never met us and know nothing about us, or maybe in a hospital all hopped up on joy juice and adrenaline. When it passes from private to public, the letters written onto a line on a birth document, a name takes on the politics, religious beliefs, and cultural and linguistic predilections of the society we’ve come from, which may well shift if we join a new one. Expectations around gender, class, and race solidify in a name, well before a person even has teeth.

Names are choices—just usually not ours. “Nobody chooses names in a vacuum,” writes Duana Taha in The Name Therapist: How Growing Up with My Odd Name Taught Me Everything You Need to Know about Yours. That doesn’t mean our parents are in control either. Whatever atmospheric pressure is in the air when a name is chosen, it may completely shift by the time a person is an adult. Consider all the parents excited to bestow Karen in the 1960s, when it was the fourth most popular girl’s name in the United States.

A personal name can have little meaning, as in Henry, which is thought to mean “ruler of the home,” or Savanna, as in the open plain. It can also bear a tremendous weight. My brother’s name, Sieu, means “superb”; drive through Fairfax County, Virginia, and he’s plastered across Vietnamese strip-mall supermarkets. I’ve long admired the Jewish naming tradition of passing on part of a deceased family member’s name to a child in the next generation. Devra, the sister of a good friend, was named after their uncle David, an artist who died young of AIDS. A few years ago, Devra, also an artist, was killed in a bike accident at twenty-eight. My friend’s son, born this year, carries the middle name Dev.

And in America, a name that sticks out can be a target. As in the journalist Riyadh Mohammed, who was advised to leave behind Mohammed, one of the most popular names in the world, when he arrived in the US from Iraq. Or the Oakland college student Phuc Bui Diem Nguyen, who was told by a professor to “Anglicanize” her name because it sounded like a swear word to him.

But a name can also blend in too well. As in the journalist whose own father would holler “Sarah Todd” when she got a call on the landline, “just to distinguish me from all the other Sarah’s who might be hanging out upstairs in my bedroom.”

To a linguistic outsider, a name can be a guess, or a gamble. As in Cyrano. Or a childhood friend of Louie’s, who was named California.

Or it can be armor. “It acted like a shield of sorts,” writes author and editor Kevin Nguyen of his first name, “One that protected me when I was out of the safety of my home.”

If it’s not already obvious, I, too, am obsessed with names, and it is because I, Thu, have picked at the scab of my name since childhood. My three siblings and I were all named by our paternal grandfather, and my parents were unforgiving of any attempt to adopt new names. My sister Phi-Hong took her campaign the farthest; tired of delightful nicknames like Hong Kong Phooey, she petitioned my parents to change her name to Kim or Linh, still Vietnamese but more manageable. She was squarely rejected.

So we don’t Americanize; we explain. “Like ‘see-you’”; “like the boy’s name Ian”; “like the number two,” none of which are quite right, but which take almost no time for a native English speaker to process. My name is not at all “Thu like the number,” it’s actually Thư, meaning letters, books. But actually, it’s Thư Hương, meaning the fragrance of literature, and it’s all the way in the back of your throat, like a jaw-ful of sung perfume. But actually in Vietnam it’s customary to drop the first of two names, so a new person meeting me there calls me just Hương, soft and light, and it feels immediately intimate. But to most everyone in my life, I’m Thu, a number, a pronoun, a particle, a dart hitting cork. I don’t ask people to try to call me Hương; I discourage it. I don’t want to hear her mutilated. (Even writing my real name in a font designed for English threatens its nature; depending on the device and browser you’re reading this in, the vowels may bulge and distort its elegance.)

For better or worse, we’re given our names, and we figure out how to deal. And in the US, some are dealt more, and deal more, than others.

I. THE BIG SMOOTH

In 1929, a young American man named John is having trouble finding a job. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa as an undergrad and has a master’s from the University of Illinois, but none of his applications for teaching jobs are getting a response. His friend and mentor, a Dr. Clark, asks if he’s ever thought about changing his name.

John’s father, Nikolai, is from a Lemko village in the Carpathian Mountains. “Most Lemkoes are themselves uncertain whether they are Ukrainians, Russians or Poles, or merely Lemkoes,” he told the Slovenian American writer Louis Adamic. “My father doesn’t know to this day. He doesn’t care. … It’s all the same to him.” Nikolai is a miner and single father to their family of five. John describes a poor and miserable childhood full of bullies; “anti-foreign” teachers who would make a show of stumbling over unfamiliar names; lunches of meager baloney beset by thick bread eaten in secret at school; being sent home for tattered clothing.

Salvation arrives in the form of an idealistic new teacher. She takes John and his sister specially under her wing, learns how to say their names properly, visits their home, and guides the children to their academic potential. So why is John, in his late twenties and decorated with scholastic accolades, unable to find a job? With some reluctance, he changes his name from John Sobuchanowsky to John S. Nichols, after Nikolai.

The account in Adamic’s 1942 nonfiction book, What’s Your Name? is at times melodramatic—but not unfamiliarly so. The trembling confusion of a young American child of immigrants, the soaring ascension past what his parents could achieve themselves, the humiliating realization as an adult that xenophobia does not dissipate in the space of a few years.

When John reveals the truth of his name to the woman who would become his wife, a tearful Mary Land confesses that she was actually born Mary Schwabenland, the daughter of German immigrants. She’s overjoyed at their chance to start over. “We are Americans regardless and no matter what! This is a new chapter, and what came before is torn out of the book,” says the future Mrs. Nichols.

But it’s this “torn out of the book scheme,” as John calls it, that becomes a rotten brick placed at the foundation of their family. Mary is intent on leaving their roots completely behind. The couple raise their daughter, Barbara, to believe she’s an old-stock American. The resentment in their union builds and comes to a head one day when Barbara comes home supremely jealous of her schoolfriend, who apparently has an adoring grandfather from Slovenia with an excellent surname, Ogrizek. Mary “sat like a statue, pale and silent,” as, slowly, the narrator tells Barbara that she has a living grandfather too, and not only that but he’s also an immigrant. And his last name is Sobuchanowsky. This sends Barbara into a fit of joyful hysterics and Mary into a “white rage.”

John’s account has a poignant storybook ending: John reunites with Nikolai, who meets Mary and Barbara for the first time. Grandfather and granddaughter become inseparable, and as anti-immigrant sentiments rumble at John’s school, the family transfers to the West Coast, Grandpa Nick along with them. Barbara insists on becoming Barbara Sobuchanowsky Nichols. “[But] the ending of the story is not completely happy,” writes John in the final paragraph, “For us of the second generation things are still unclear.” It seems that the earlier chapters of the book, torn out and then hastily stapled back in, don’t quite fit the original binding.

The problem of a name in America is the problem of the American experiment in microcosm: How to shove the world’s phonetics and conventions into mouths and minds that consider Anglo whiteness and the English language to be the default.

Eighty years ago, it was the newest immigrants—from Ireland, Italy, Russia, Poland, among others—to the US who were charting a path through its Anglo-Saxon waters. What’s Your Name is a delight to read, not only for how clearly its themes resonate almost a century later, but because it’s an extravagant twist of vowels and consonants, a bounty of Kwaiatkowskis, Vojvodichs, Maksymyks, Kalakukas, Robinovitzes, Siranooshes thrown like confetti across the otherwise English page. Adamic was a vocal proponent of multiculturalism, and he was prescriptive. He believed that, if necessary, names should be slightly sanded down to be more manageable for English speakers (as in the case of the original ç in his surname), but that an Anglo-Saxon cultural ideal was a relic, and clinging to it, a fallacy. “Where does ‘reasonableness’ as to names begin and end? Whose ‘reason’ is going to approve which name?” he wrote.

For Adamic, names were no less than the core of an American culture war: “These are the circumstances, the weapons, the elements, the issues, the lineup of the psychological civil war of which the battle of names is the most obvious part,” he wrote. “Complicated as is the question of names, I believe it is but the clearest manifestation of immense and as yet barely recognized cultural stirrings in the United States.”

Not all name changers were hand wringers. In 1948, Beverly Winston wrote that when she changed her name from Beverly Weinstein, she had no intention of abandoning her Jewish community or identity. “She viewed her new name simply as a piece of acceptable clothing, like ‘a corset, shoulder pads, or a “sincere” tie,’” writes Kirsten Fermaglich, a professor of history and Jewish studies at Michigan State University. Fermaglich’s 2018 A Rosenberg by Any Other Name: a History of Jewish Name Changing in America is a far more sober, largely angst-free academic volume that argues against the image propagated in popular culture of the self-hating Jew passing as a gentile while their secret eats away at their soul. Especially by the late 1940s, says Fermaglich, name changing among American Jews had shifted away from anxiety over anti-Semitism and had become a tool for the upwardly mobile. The fees and petition to have a name legally changed, after all, were not cheap. In 1948, The Atlantic published an account by “An Anonymous Jewish American,” a journalist who filed to change his last name, along with his brother, a few years prior. The total cost for “having joined the human race” was $60, several hundred dollars in 2021.

“The goal,” writes Fermaglich, “Was simply to manage Jewishness so that it did not interfere with mobility.” Avoiding potential friction was a way of “covering” (as distinct from passing), a term coined by the sociologist Erving Goffman. In his memoir of cultural and legal criticism, Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights, Kenji Yoshino defines it as “ton[ing] down a disfavored identity to fit into the mainstream.” The first examples he gives are Ramon Estevez, who became Martin Sheen, and Krishna Bhanji, who became Ben Kingsley.

Many of the name changers described in A Rosenberg by Any Other Name were simply fed up. Bosses and coworkers were unable (or unwilling) to spell or pronounce names correctly; people had problems with getting mail delivered; others had embarrassing miscommunications over the phone. “Jewish names were conspicuous and drew attention to their possessors,” writes Fermaglich. “They required individuals to think about those names daily as they managed complicated relationships with both Jews and non-Jews.” A friend tells me of his grandfather and great-uncle, who changed their last name from Feinberg to Foster, because it sounded “too Jewish” for lawyers. I hear from an in-law who only recently, at fifty years old, found out his Grandpa Marty was actually Grandpa Moses.

Names morph, run wild. Name trends, like new words in a language, do not follow an obvious logic, cannot be tested in a lab. So American immigrants attempting to cover and assimilate have given rise to new, unexpected norms. As Fermaglich writes, Jewish American parents, doing their best to pick American names for their children, gave them English surnames as first names; Norman, Stanley, Milton, and Irving have since come to signal Jewishness.

There are also “Chinese sounding” American girls’ names: Amy, Jenny, Grace, and Vivian are disproportionately popular among Chinese Americans versus the general public. Andy, as distinct from Andrew, and Dan, not Daniel, are disproportionately popular Chinese American boys’ names. Kevin Nguyen is common enough among Vietnamese Americans to be its own meme.

II. SPELL CHECK

The story of a name in America is one of racism, xenophobia, language, history, ancestry, community, identity, fathers, mothers, sons, sisters. It’s also a civilization-level clash of paperwork.

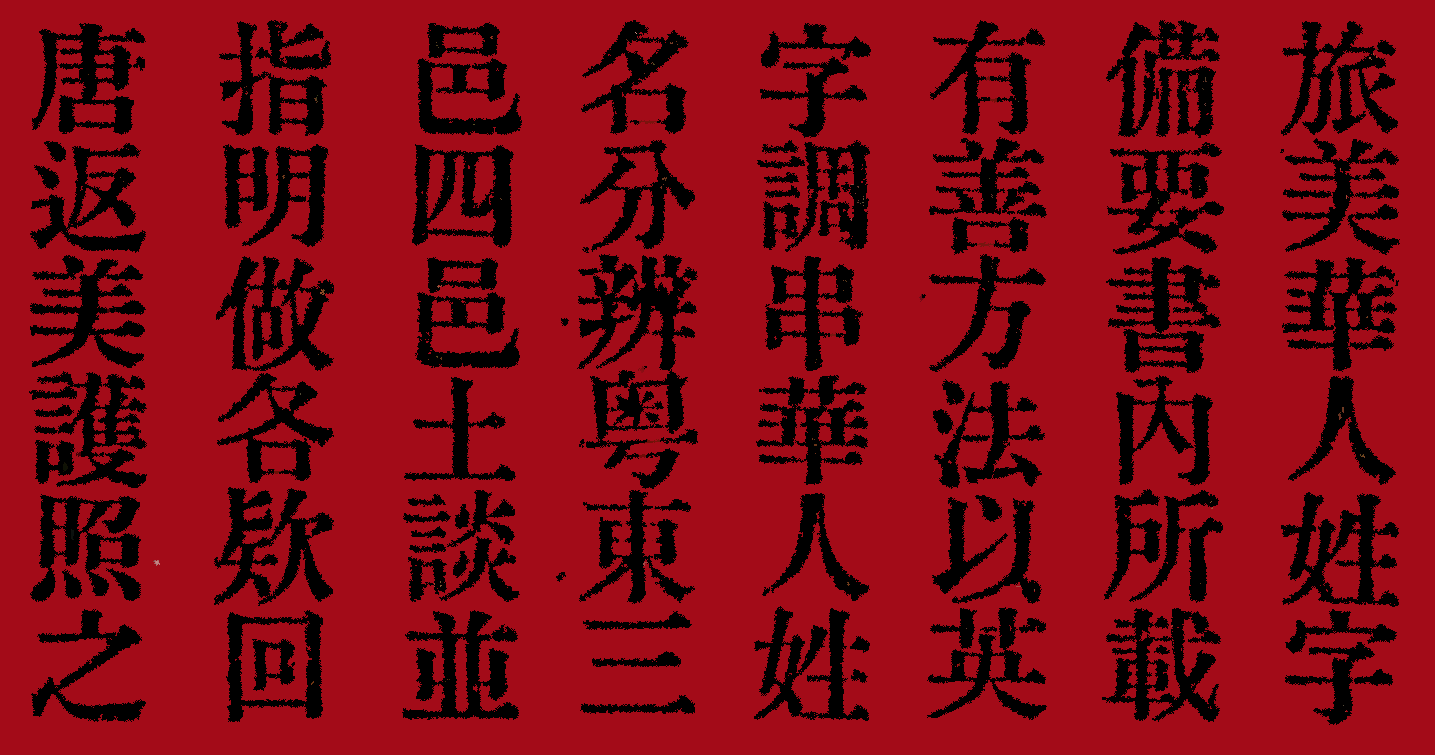

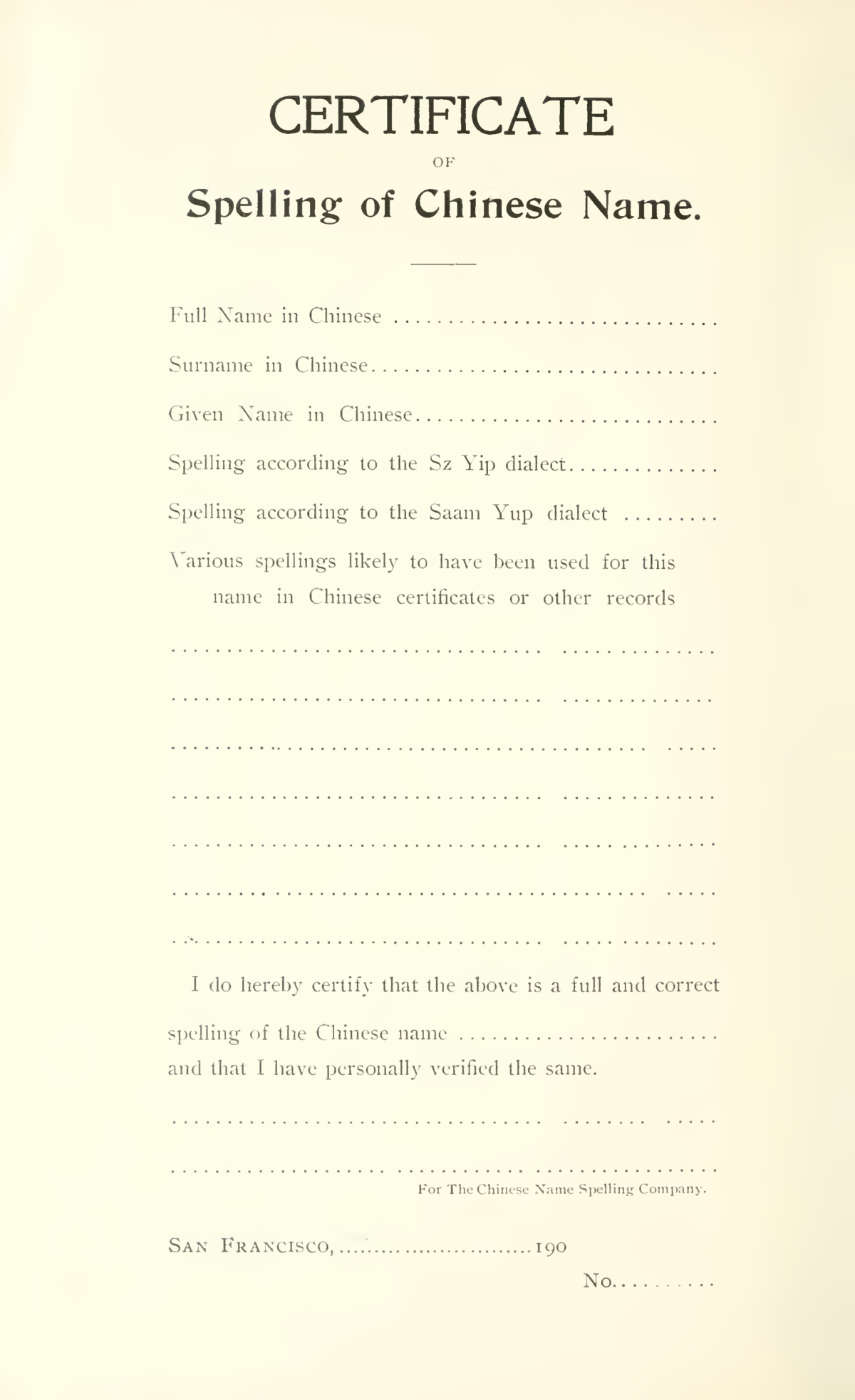

In 1904, the Chinese Name Spelling Company published a slim volume called The Surnames of the Chinese in America. The first twenty pages offer a standardized list of transliterations of Chinese surname characters according to the two dialects most common in the US at the time. “The David Jones System of Spelling Chinese,” devised by the official Chinese interpreter for the US Courts in San Francisco, is recommended and signed by a US attorney and three clerks.

The last fifteen pages of the booklet lay out in English and Chinese the bureaucratic regulations of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. To leave and return to the US, an immigrant registered as a merchant (and not as a laborer) had to produce an affidavit “signed and sworn to by two witnesses who are not Chinese.” Throughout, the publisher stressed the importance of consistent spelling to avoid bureaucratic confusion and possible deportation, and, naturally, offered its own services as a solution: For a fee of $30 in today’s dollars, someone from China could get a certificate of all the possible spellings of their name. “For contracts, leases, wills, deeds, affidavits, store names, and for all kinds of legal documents in use in Courts, United States Customs, Internal Revenue, and Commerce and Labor Departments of the United States, Bureau of Immigration and Chinese—such as writs of habeas corpus, bonds of appearance and appeal, certificates and affidavits on appeal, applications for duplicate certificate of residence, partnership lists, statements, etc,” says the booklet.

The imprecise process of transliterating Chinese characters to the English alphabet is just one of a number of frictions between name conventions, many of which echo across Asia. The boxes of one custom simply don’t transpose onto those of another. An obvious example is that names from China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan do not map to a first, middle, and last name. Even for Chinese researchers of her generation, Louie writes, it was not always clear how to adapt to the new system or to interpret individual choices. Should the two customary monosyllabic characters get forever conjoined into one polysyllabic name? (As in the artist Dong Kingman.) Or separate but hyphenated? (As in Yo-Yo Ma.) Or would initials be easier? (As in I.M. Pei.) And hang on… which is the surname? Louie tells me about a family in northern California that descended from a man whose first name was Lee and surname was Lum. But when his name was recorded, the order got swapped, and the Lum family henceforth became the Lee family.

A 140-year-old decision to conform to the order of Western names is playing out today at a global diplomatic scale. Japan, where I currently live, is consistent with other Asian countries in that the family name is given first, then the personal name. But a perhaps uniquely Japanese twist is that when names are spelled out in the roman alphabet, it’s customary to reverse the order to accommodate the Western style. So a business card with the name 中島祐希, “Nakashima Yuki” (surname, first name) would likely have written underneath, “Yuki Nakashima” (first name, surname). I have a debit card and an ATM card issued from the same bank, one with my surname first and one with my given name first.

But there’s a growing call to rethink the convention, which was adopted during Japan’s era of concerted Westernization. In 2019, Japan’s minister of education proposed that the government revert to the traditional name order wherever their names appear in the roman alphabet. The statement caused a ripple of confusion across English-language media outlets and is how the new Japanese prime minister appears as Fumio Kishida (first name, surname) in The New York Times and Kishida Fumio (surname, first name) in The Economist, but Xi Jinping (surname, first name) appears as such in both.

III. ON THE LIST

In fact, the US is relatively liberal about names. Until 1993, France had a list of acceptable names that parents legally had to choose from. Hungary and Denmark still have such laws. Australia doesn’t allow, among other things, names that are too long, and names that could be confused for official titles or positions, like Queen or Colonel or God. In most US states, it’s legal for adults (that is, those not in the prison system) to just choose a new name and start using it, without having to notify the court. So why do people still line up or shell out cash to make it official?

“Legibility” is a term in state-making that refers to the process of mapping citizens: to categorize and arrange peoples, in order to, among other things, tax them. In 1890, the US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Thomas J. Morgan, gave government officials and school superintendents permission to assign English names to native peoples in cases where their naming patterns didn’t fit the English American standard. He was especially preoccupied with the tribes in which members of the same family didn’t share a common surname, which he thought would make a bureaucratic mess of land inheritance.

The ability to have one’s name be easily legally processed is quite literally part of what it means to be a citizen in the eyes of the government. In Australia, if a baby is given a name that is prohibited by law, then the state will simply assign them a name, so the birth can be legally registered.

As Fermaglich and Adamic both argue, over the last century the US ramped up citizen-making measures: ration cards, veteran benefits, the draft, welfare checks, insurance policies, home ownership, and a worldwide passport standard. Toward the end of the century, the government started making legal services cheaper and more accessible. And then in 2001, the US entered a new era of government surveillance. All of this meant that people started showing up to court not to give themselves new, easier to pronounce names; instead, in the age of paperwork anxiety, they were lining up to fix mistakes on their documents. Echoing the Chinese Exclusion era, now it was not just having a name, but having consistent, identical versions of that name, that allowed a citizen to be processed by the state.

It’s not hard to see how a list of names can be abused, and even weaponized. One might have expected 9/11 to give rise to a new wave of name changes for Arab Americans. But reality folds back on itself: Arab Americans came under such scrutiny in the years after the attack that a petition for a name change could itself be a red flag. According to Fermaglich, in 2008 the NYPD started requesting and compiling petitions for name changes to and from Arab-sounding ones. The following year they started running background checks on people on those lists and calling them in for questioning.

“Names are everywhere, and because they’re everywhere, they have a power we’re not even aware of,” says I.M. Nick, the editor-in-chief of Names, a journal of onomastics, and the former president of the American Name Society. Nick is also the author of Personal Names, Hitler, and the Holocaust, a socio-onomastic study of genocide, and for her, a state-maintained list of names automatically sets off alarm bells. In Edwin Black’s 2001 explosive bestselling book, IBM and the Holocaust, he investigates the Hollerith punch card reading machines made by IBM, which he argues were leased to the Nazis to identify, sort, assign, and transport the people selected to be sent to concentration camps. He writes, “IBM Germany invented the racial census—listing not just religious affiliation, but bloodline going back generations. This was the Nazi data lust. Not just to count the Jews—but to identify them.” Even more unnerving than a list of names, it seems, is how readily it can be processed.

IV. DOES NOT COMPUTE

One morning in August I lined up in Manhattan to get a free COVID-19 test. Half an hour later, I watched as the guy ahead of me in line went to get swabbed, as I stood huddled with two staff members, staring at a computer screen and muttering through our masks about how to deal with the fact that my driver’s license has no hyphen but my other IDs, including my passport, do. At last one staffer threw up her hands. “Give her the hyphen.”

The forms we fill out have multiplied over the years, and so, too, have the rigidity of their boxes: In a globally connected world, digitization hasn’t set our names free; instead, it creates and reinforces what counts as a name. Hyphenated names throw web errors; names with spaces are pushed together; names too long for the character count are cut off midway; two last names become a middle and a last. Autocorrect reminds us over and over which names are recognizable, as it denies the existence of others. (In my phone, Bich Ngoc becomes Bich a fox; Lotfi becomes Lotto; Kato becomes Mayo.) Having an “unmanageable” name today does not just mean that your boss will flub it in front of everyone at work, or that your teacher will pause with dread after the name in front of yours. It means that a site asking for your credit card information will reject you, will rebuke you with: “Please enter a valid given name.” It means your text documents will zip a red squiggle under your name, saying that the computer can’t find you.

Once you bring up name pains, people want to talk. My friend whose last name is McCoy remembers an airport ticketing kiosk in Singapore that rejected her reservation because the second capital in her last name didn’t register in the system. A friend whose last name is True got called down to attendance in elementary school because his name rendered all the other kids’ names “false” and wiped them from the spreadsheet. Before the days of email, one of my sisters couldn’t register her last name in the company voicemail registry because it required three letters, and ours has only two.

Teake is an artist and movement specialist based in Los Angeles. His first memory of coming up against his name is from around age five: At the end of a school trip to the public library, Teake tried to check out the book he’d chosen. “I couldn’t,” he says. “They were like, ‘That’s not a real name.’”

“I don’t think I was emotionally invested in the book,” he says, laughing, “But that leaves a mark.”

Teake has one name. He doesn’t think of it as having only a first name or only a last name; it’s just the one. It’s not a family tradition that’s been passed down, nor does it come from any particular ethnic or linguistic heritage. His parents both have first and last names; he and his sister were given just one each.

A call to his parents, who knew how Teake’s library credentials were registered, eventually resolved the issue. And that day young Teake learned an important lesson: “This is part of life now.” Teake understood that having a name that did not technically fit in the system meant he’d have to be the one to adapt. Enough encounters with disbelieving authority figures has taught him to have copies of his identification documents at the ready at all times, including his social security card. Enough problems at the airport has taught him that there’s a special code for people with only one name, and he just has to find someone who’s heard of it. Enough error codes on webpages has taught him to be creative in filling out registration forms. “But then I have to remember how I was creative the first time,” he says, laughing again.

It seems like a lot of burden for one person to carry. But Teake doesn’t seem to mind, and he says though he did have thoughts about changing his name when he was younger, he no longer considers it. But his sister did. “We’re not ones to look for approval from anyone else,” he says. “That was a pragmatic decision. No value judgment around that.”

Why do this to a child? one might ask, not without reason. Teake says that the answers and rationales he’s gotten have varied over the years and from parent to parent. But he says he’s comfortable with the ambiguity, speculating that perhaps his name has attracted, or forced him to seek out, more open-minded people and communities. Indeed Teake clearly eschews a host of conventional identities; he playfully resisted a number of biographical questions I asked him (age: “thirties/time is a construct”; race/ethnic heritage: “ambiguous”; pronouns: he/they/“fluid and not too attached”).

V. CUSTOM MADE

“A lot of people just decided that they weren’t that person…That’s not my name, I don’t like that name, I want to give myself an identity,” filmmaker Banban Cheng tells me. They describe coming out when they were younger, and making friends they know only as Tiny, Pants, and Yes. I met Cheng over a decade ago, but, until very recently, knew them as Ang*la.[1] For reasons that might be obvious to anyone who’s met the compact Houston native with a dry side-smirk and self-described “butch body, femme heart,” the name didn’t quite fit. “There was always a bit of a distance between people who knew me by Ban or Banban and people who knew me by Ang*la, culturally speaking,” they say.

In 2020, reports of hate crimes in the US against people of Asian descent were up seventy percent from the year before. A conversation that Asian Americans had been having amongst themselves, about the lasting effects of assimilation, about being an invisible minority, and about where they fit into the fabric of the country, seemed to reached the national consciousness at last. And Cheng, who had felt this gap in their two names, felt spurred to act: They decided to drop their given English name and publicly adopt Banban, the name they’ve long gone by at home and in their Taiwanese American community in Houston.

(I’m reminded of a passage from Adamic, writing eighty years ago: “I hear that in 1942 many of the Japanese Americans evacuated from the coastal areas of California, Oregon and Washington switched back to Japanese given names: Mary to Mariko, Lillie to Liliko, etc. One youngster said: ‘Since they insist on considering me a “Jap,” I may as well have a Jap name!’”)

“Ang*la is so feminine,” they tell me. “Banban had always felt more right.” Banban is gender neutral; it was chosen by their maternal grandmother after a literary brother and sister duo, each of whom had Ban as part of their names. “I want to say they were warriors, but I could totally be making that up,” they say. Banban is something of a sobriquet; their other given name is Zheng Ying-Ji, the latter of which sounds a bit like Angie. Cheng wonders how their immigrant parents knew it was short for Ang*la.

It turns out to be a surprisingly common choice. According to one informal inquiry from 2009, Ang*la is one of the most popular English girl’s names among Chinese Americans. Indeed, there was another Ang*la Cheng that went to their high school. “One time the NSA came to visit our house,” they recall. Cheng had a school assignment in which they had to write to a celebrity, and they chose John Warnock Hinckley Jr., the man who tried to kill Ronald Reagan as a “love offering” to Jodie Foster. “You’d think it was because I was obsessed with Jodie Foster—but it’s not. It’s because I was obsessed with Ronald Reagan,” they tell me, smirking. The NSA, it turned out, went to the wrong Ang*la Cheng’s house first.

Cheng readily admits that by nature they don’t feel comfortable taking up space. “It was awkward at first to be like, ‘Pay attention to me! Now, this is my name. It’s gonna be inconvenient for you to try to say it,’” says Cheng. “When you slip up, it’s going to make you feel kind of weird, and it’ll make me feel kinda weird, too. But, like, let’s try to do this together.” Cheng didn’t start out thinking of Ang*la as a dead name, but now as more people get used to Banban, the old name is moving farther away. “It just feels simpler to commit to Banban rather than have the other name looming in the background,” they tell me, “Like I have two identities or something!”

For Vinh, choosing a new name felt like a necessary step in coming out. “At the time, there was a feeling like, ‘If I don’t do this, I’m faking it, I’m not doing it right, it makes me less trans or something,’” he says. Last spring the twelve-year-old New Yorker told his family that from now on he’d be using he/him pronouns, and that he would go by Ren, a name he’d been using online. He’d chosen it based on Wren, a character in the dragon fantasy series Wings of Fire. His mother balked—not at the new gender identity, but at the name. It wasn’t Vietnamese.

“I guess the main conflict about me coming out was just my name,” Vinh says. He had already become attached to Ren, which is popular in Japan and vaguely Star Wars-y in the US, but he understood it was important to his mother that he have a Vietnamese name. All the family on his mother’s side have Vietnamese given names—and just the one, not a Vietnamese legal name and an English nickname. That includes me, Vinh’s aunt.

From childhood my siblings and I have been saddled with names that branded us, with peers and teachers and bosses whose mouths couldn’t form the ieu and oa and ng sounds. I see a mix of pride and wary pragmatism reflected in the next generation of our family: my six (soon to be seven) nieces and nephews have all been given Vietnamese names that are relatively easy to pronounce, with spellings that are unlikely to strike fear into the heart of a new teacher on the first day of school.

A new name would mean flying in the face of generations of family tradition. But Vinh didn’t ask for any of that baggage; none of us do. Here was a moment to consider: Can we all, beyond getting married or coming out, break free of our clunky inheritances? Is there a future in which we continuously reassess our names throughout one lifetime, interrogating them every few years to see if they still fit, if they still speak, if they still call on us the way we call on them?

Maybe. But for here, for now, a compromise. Ren with friends, Vinh on paper and with family. Perhaps the two names will be met with wrinkled foreheads of incomprehension, will require extra murmured explanations, will cause confusion and cases of mistaken identity. But that may very well be the weight of moving forward.

[1]Cheng agreed to share their given name, Angela, publicly for the purposes of this article. We use Ang*la to denote this is a dead name.

More Reads

Close Read: Thiago Rodrigues-Oliveira, et al.

Veronique Greenwood

Take the W: Entry Points

Katie Heindl

Credit: Creative Commons, johnmac612, CC BY-SA 2.0. When I started writing “seriously” about basketball eight years ago (before that, I wrote NBA fan fiction for David ...