I have an impossible memory of my aunt Martha. She is in a dance studio in dancewear—the 70s—tights and solid-color cotton. I don’t know if she’s walking or standing or sitting—maybe, through the course of the memory, all three. I am aware of her lithe body, the sweat on her skin beading in a late afternoon light. But my attention is on her face: smiling, post-exhaustion, so happy and tired like only a dancer, like only a mother, could be. The dance studio has a wooden floor—an old warehouse or factory floor—which has been sanded and finished in a honey sheen. And the whole space is awash in light. Sunlight through the rolled glass of the woodframe windows. Everything is sepia with the light, and her face hovers in the halo of her hair, iridescent with that rose sunlight of the American Southwest.

I say it’s an impossible memory because, even if something like that did happen, I couldn’t have been more than two at the time. How could I remember that? I do see from the vantage of a child: about knee high. My Aunt Martha is smiling—she is afire with the light—and I am standing close by, as if I am ready for her to take me and lift me onto her lap.

A memory I have of Martha that I know is genuine: I am in the room where she is. It seems like a hospital room, but I hadn’t known we were in a hospital until I entered the room. There is a signing book, and I am at it, and there is one of those toy bubbles that you buy from the coin machines at the supermarket, and it has a toy in it. And the toy and the bubble are attached by a string to the signing book, which I can’t read because I can’t read yet. And I’m semi-consciously noting how curious the toy bubble and the book are, and how I’m disinterested. And Martha, who is sitting up in her cranked up bed—she is pale as death, and will die, even a child knows—she says to me:

“Golden boy. Where is my golden boy?”

I don’t remember the funeral. I was about five. She was twenty-eight.

Did I mention that Martha was beautiful?

Calavera Azul by Sylvia Ji

I’ve been thinking about Martha as part of a longer piece about my grandparents. My grandmother, with Munchausen by Proxy, killed four or five people—mostly by accident, but still. (My experience with the police—I’ve talked to them—is not exactly CSI.) One victim was her husband (her second husband, who was terminally ill, and took a very sudden turn for the worse), one was her lover (he was younger than her, in his 70s, not 80s, but he kept breaking limbs, and after Grandma’s series of several frantic calls about the level of care he required, he dropped dead), and two were her children. Martha and Norman. Or, well, I shouldn’t blame Grandma entirely. Martha died of melanoma, which doesn’t usually kill people (though Grandma may have cared for her to death), and Norman died in a scuba diving accident.

To explain: Grandma didn’t want Norman to go diving that day, but he had already put money down for the boat (scuba diving is very expensive), and he insisted on going, so she poisoned him, probably with prescription pills (but it could have been vitamins, she had been a nutritionist), and then when he went anyway he made a fatal miscalculation (he waited, um, on the sea floor, for help).

Should I say that my brother, my mother, my wife and I all believe this, but hope to be mistaken? My parents were very young when they had me, and until I was old enough to care for myself, Grandma would take me in for weeks at a time, and at Grandma’s I’d be amazed by this unusual thing that happened, which I assumed happened to everyone. Sometimes I would sleep for 48 hours straight. Also, a few times in the middle of the night, maybe half a dozen, I had trouble breathing, and Grandma had to rush me to the hospital.

Santa Muerte by Joahannah von Frankenstein

Amore de Mori by Kelly Durette

***

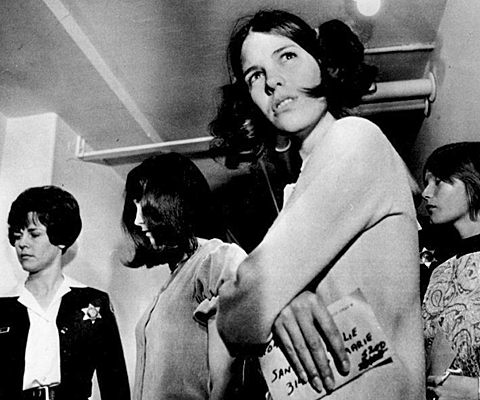

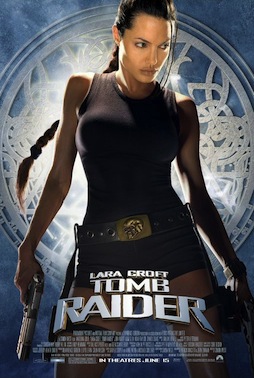

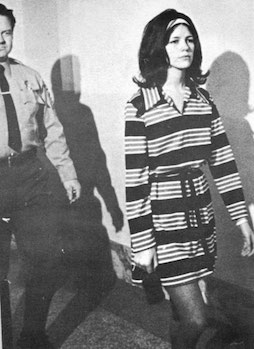

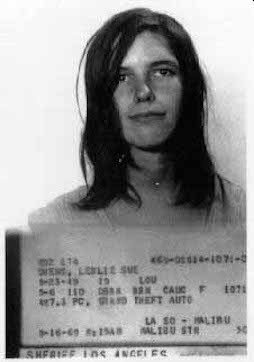

Do you know who Leslie Van Houten is? She was the hot Manson girl. Here she is walking to court in 1969:

And here she is at a parole hearing a few years ago:

She’s still quite attractive, don’t you think? That’s been a problem for her. “All dolled up,” said Prosecutor Stephen Kay in 1978, during the course of Leslie’s third trial. Now she makes a point of showing up to her parole meetings wearing prison garb, no make-up and hair pulled into a bun.

“All dolled up” was an inspiration for me. I’m working on a Leslie Van Houten paper-doll book. It will come complete with multiple outfits and the rest of the Manson gang. One of the arguments that the Manson people put forward (only a few are still aligned with him) is that “The Family” is a creation of American culture, a reflection of whatever American culture is at that moment. At the moment of the Manson murders, America was in the act of a massive, brutal, senseless murder of innocents. The Family’s maybe dozen murders (my estimate) were nothing compared to Henry Kissinger’s illegal bombings of nations we weren’t at war with, which is to say, Henry Kissinger’s murder of 200,000-300,000 people. Kissinger’s slaughter is all documented, everybody knows he’s a war criminal (he’s wanted in numerous nations), but he’s still O.K. for Harvard or network television or American History.

When I think about Charlie Manson, when I think about his crimes, I think his great mistake was in choosing his victims. He had a group of militants that he had trained, fanatics who would do anything, kill anyone. He targeted local drug dealers who were sort of on his turf, a B-movie costar, a hairdresser and a grocer. If only he had killed Kissinger, some future generation would put him on a stamp.

My aunt Pam was a Beatlemaniac. So was Leslie. Before I was born, my mother and father drifted around the American Southwest—the deserts where Manson took the gang to wait out the Armageddon. When I think about the Manson crowd, running around making movies, making art, making music, I think that they were basically the same as the Warhol crowd, but not in New York City. Not easy to accept, but much of young America in 1968 and 1969, the crossing over to Manson territory was a few more acid trips and one or two really out-there friends.

Oh, and my father was a militant. He spent several days in the New York City tombs for “attacking a foreign embassy.” He’d been putting up vague “stop killing babies” posters with a friend, and he was arrested. The posters were about Vietnam, but he’d inadvertently put them up on the Lebanese embassy. The Lebanese were completely freaked out, and the authorities feared an international incident.

Oh, and my aunt Martha really was an underground operative. My parents lived in New Mexico when I was a baby. One of Martha’s entourage was a draft dodger (my father had evaded the draft by dieting down to ninety pounds.) When Martha and my mother and the gang went out to a “rock concert,” the police raided our house. My father, who had stayed behind with me, managed to talk his way out of getting arrested—someone had to care for the baby, he argued.

At Spahn Ranch, in the Manson days, there were more than a dozen children running around.

***

In the late 60s, the war with conservative culture—obese, carcinogenic, bureaucratic, homicidal conservative culture—was on. And my side was winning. It’s easy upon reflection to say that Manson and his people were lunatics, but their lifestyle was indistinguishable from the young dropout scene in the States and all over the world.

And Leslie, far from what she really was—an acid-melted, brainwashed, nineteen-year-old—has been cast as Girl Death. She is the Skinny Girl.

Santa Muerte by Chris Parks

The skinny girl is Santa Muerte. Sometimes she’s pretty, and sometimes she’s terrifying:

Sometimes she’s helpless:

Ophelia by John Everett Millais

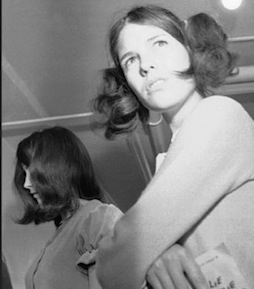

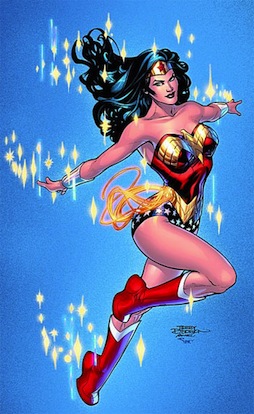

And sometimes she’s justice:

Sometimes she promises peace, and sometimes she promises war:

And sometimes she’s all of the above. Here are “The Manson Girls,” Susie, Pat and Leslie, on a perp walk in 1969:

Here’s just Leslie:

Here’s Athena:

Athena by Taregh D. Saber

Here’s Judith, my mother’s namesake:

Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio

Here’s my mother, 1988—a full page for a newspaper artist interview in Cover Magazine (note the heads):

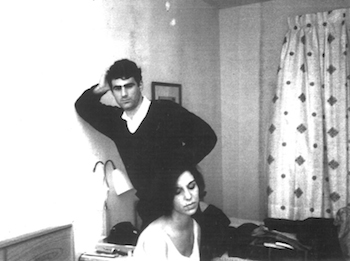

Can I show you a picture of my Aunt Martha?

She’s with her husband, John. John looks like my father, and both of my mother’s husbands, and, uh, a little like me.

Agatha, Martha’s daughter, is a just few years older than me. As a young child, I adored Agatha; she was like a sister who cherished me. When we were both visiting Grandma, we would walk to M.H. Lampstons, a knick-knack store, which was the only thing to do in Merrick, Long Island. After her mother died, we walked there, as usual, but on the way she made a mean, horrible face. She terrified me with it all the way to the store and back. I was so marked by the face, I learned how to make it. I look a little like the joker, no?

My image of the skinny girl comes from my memories of Martha, as well as memories of Barbara Moynehan, a beautiful, charming friend of my mother’s about whom I fantasized throughout high school. She died suddenly of cancer.

I expect that my experience of death is rather ordinary: death has come to the young and the old; death has not been greedy, and death has not been generous.

Oh, and I meant to show you. This is Agatha:

Photographed by John Wyatt

I don’t see Agatha very often, but I still miss her like a sibling, and I feel, or I imagine I feel, a connection with her—that she also took her mother as The Skinny Girl. I think she made it a part of her look, don’t you?

Do you think that through loss, people could share something so intimate?

Death is a personal lover to each of us, and she/he will tailor a face, an irresistible allure, that is at peace with your memories, your character, your body, your thoughts, and your desire.

***

Here’s Leslie’s mugshot from when she was arrested for grand theft auto in 1968:

Leslie was only present at the murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca (not the Tate murders), and she’d probably only been stabbing a corpse—stabbing that was more like “scratching,” according to the autopsy report. Sharon Tate’s sister, Debra Tate, hates the idea that Leslie may not have killed anyone; it comes up at the parole hearings. Back in 1969, Leslie was the first family member offered a deal to testify. When she didn’t take the deal, the prosecution granted immunity-for-testimony to Linda Kasabian, who was a party to both sets of murders, and a pretty shady young woman (who continued to be pretty shady), but looked blonde on the stand and played up the young mother thing (her kids are also in and out of deep trouble).

Leslie was the beautiful child, the radiant child, and I would guess the smartest (like doctor, lawyer smart) of the Manson family defendants.

But Leslie, Ophelia and Joan of Arc, was the most adaptable, the best canvas for a national Skinny Girl: a new, American archetype. She could be crazy, or she could be evil, or she could be helpless, or she could be innocent.

***

My grandfather David recently passed away. When I was about thirteen I saw an old picture of his cousins. I realized, immediately, that I found these cousins attractive. They looked just like the women I’d been attracted to, and that I would be attracted to all my life. I’m sorry I don’t have the picture of my cousins. My aunt Pam is still looking for it.

My aunt Pam is very beautiful—a tall runner who has a soul maybe twice as big as everyone else’s. She won’t give me a picture to show you. (And maybe this is the best place to tell you that, honoring my father’s wishes, I’ve revised this essay since it was first published. I’ve removed an image of me and my father, and images of my grandmother and great grandmother.)

This is a woman I dated in college. Here she is, back then—she’s playing a man in a play:

This is a woman I dated while I was in school.

This is a woman I dated in my late twenties:

This is the woman I married:

I took the picture the night we met. We were on the stairs in a gallery building in Chelsea. “Why are you taking my picture?” she asked me.

This is Josephine Meckseper, who I used to pal around with:

People often mistook Josephine for my wife, and my wife for her.

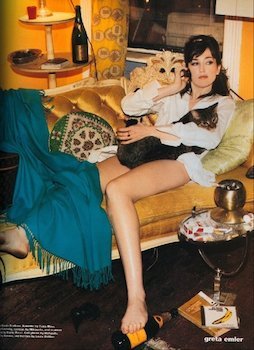

Here’s Greta, another old friend (in a magazine in 1999):

This is Miss Emily, a webcam model (one of my favorites), who read a sonnet of mine for Vice Magazine:

I think Miss Emily looks like Agatha, don’t you?

***

I’d very much like Leslie to be released so she could shoot Henry Kissinger in the head. But then again, he’s quite elderly, and will probably die soon anyway, and I don’t want to spare him any suffering. For there to be any justice in this world, she’d have to torture him first.

Recently, I met a young Manson acolyte. She’s a stunningly beautiful twenty-five-year-old former child actor who just got her MFA in creative writing from Columbia University, which is where I picked up my MFA (I’ve also been up there a little as faculty). Of course, she’s not a Manson acolyte; she’s working on a novel based on a peripheral player. She seemed to be only slightly more interested in Manson than me.

The only thing that interests me about Charlie: he was a perfect doll. He was tiny, and the women dressed him up, and he dressed himself up: Charlie the Cowboy, Charlie the Revolutionary, whatever. The clothes in the group were communal, and the women wardrobed from a pile (sometimes they secretly stashed things for themselves). Dress-up was a Spahn Ranch theme. Leslie would be “cowgirl” when she led tours of the old western sets—or, for a party, she’d be motorcycle girl. The women wore what they felt like wearing, or what Charlie felt like having them wear. (To best pimp them out to men that he thought were powerful or necessary.)

Oh, I should mention: rape was also a part of The Family life. Steve “Clem” Grogan was a rapist, and (in the opinion of this writer who’s been reading Manson junk for three years) a casual murderer of hitchhikers. Bruce Davis (also, uh, my educated guess) was another murderer of his own accord.

Oh, and by the way, Steve “Clem” Grogan, aka “Scramblehead,” has been released. Oh, and Bruce, who some people think was involved in the Zodiac killings, was just granted parole. Bruce is born-again. Tex too. Tex, a little older than the other Mansonites, was the spree-killer who carried out the Tate and LaBianca killings. Oh, and the late Susan Atkins too, born again. Oh, and Catherine “Gypsy” Share. Born-again. Oh, and Bruce and Tex are clergymen; they speak for Jesus. (Leslie has remained a godless Pagan.)

I should maybe also mention that I’m also attracted to Barbara Hoyt. As she was in 1969.

Barbara has also become a Christian. She’s outspoken about keeping Leslie and the others in jail. I agree about the others, but not Leslie. Also, I miss the old Barbara. The family liked to boast how healthy and beautiful the girls looked when they were with Manson, and Barbara was indeed slender and gorgeous when she was at Spahn.

Do you think she looked a little like Leslie? And maybe my grandmother?

It is very difficult to get into the headspace, but in 1968 and 1969, there were 3000 campus bombings, political hijackings every day—planes, buses, trains, everything—and a continuous violent clash between protestors and police. Add to that a suffocating, endemic oppression of women and minorities, and a grotesque repression of creative culture. Once, I said to my mom, “the revolution almost happened.” And she said, “John, it was on.”

Could my mother have been a Manson girl? Well, she wasn’t flaky enough. But her sister was. My father? No, but he was in love with the same desert landscapes as Manson, Death Valley, etc. Also, many of Manson’s religious ideas came from the gnostic Christianity then going around—and my father went so far as to live in a monastery. Pretty spacey. And the kind of upbringing I had—the child of a failed open marriage, the clan-living parental style, the willful absence of authority (I called my mother and father Judy and David)—is right out of the Manson playbook. My friends, including me I suppose, looked just like the kids at Spahn. Maybe the 70s wasn’t entirely made up of hippy parenting, but what, 10%, 25% of kids lived a prehistoric lifestyle?

The Manson group picked up a term. “Alaman.” Maybe from the German surname Alaman, meaning “All men,” or maybe from the Islamic story of Al-aman Mirza. To the family, an alaman is someone who is to you a mother, a father, a son, a daughter, a sister, a brother and a lover. The Manson ideal, which is arguably the Christian ideal, and arguably the ideal of Buddhism, is to treat everyone as your alaman. And that’s why Leslie is so particularly interesting, and so particularly threatening. In the same way I identify with Leslie, see her as my mother, my aunt, my wife, my girlfriends, my children, and the sister I never had, other people can also find sweethearts in her. She has been so demonized, been made so disproportionately accountable, that our will to forgive her, however conscious, is overwrought, and her appeal brinks on the divine.

***

Bobby Beausoleil, Leslie’s boyfriend, the one who brought her into the Manson group, was something of a clown.

John Waters made an appeal for Leslie’s release, which fell flat (he published the plea in the Huffington Post as a 5-part essay, which he then included in a book of his writings). Not even I found Waters convincing. John, like Bobby, is something of a clown.

The clown iconography has historically been associated with “The Skinny Girl,” as has Hades, a.k.a. the devil.

I own the candleholders. My Aunt Martha bought the top one at a fair. I decided I needed two, so I bought the second one on the internet.

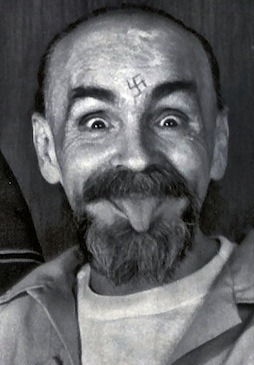

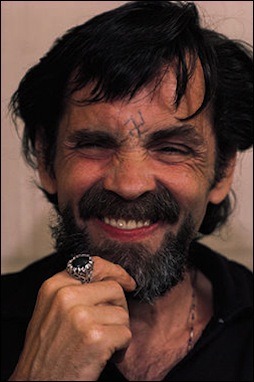

Look closely. That face, that demonic face, is the face my cousin Agatha taught me.

Manson has a few versions of it:

My mother is a painter. The second painting she made (she was a child, but this is somehow her second painting as an “artist”), was a portrait of a jack in the box, which had a devil face. It was terrifying, but my favorite. My mother recently sold my grandmother’s house; she didn’t move out before the buyers took over. They just threw everything away, I guess. Including that painting. It was the big scandal in Merrick: the buyers tore the house down.

This is a portrait of my aunt Martha:

My mother painted the portrait. It lived at the top of the stairwell, which was dark and covered in moldy blue carpet that was loose. It was here that I was molested by Peter, an older boy who lived down the block. Peter shared a demonic smile with my uncle Norman. A self-portrait of my mother lived at the bottom of the stairs:

There were other portraits in the house, but these were the two I saved. The house smelled like mold and baby powder (which resided on the water tank in the bathroom, because my grandmother didn’t believe in flushing the toilet every time—the baby powder would suffice.) The house was cold in the winter.

Ok, confession, I found out very recently that the first painting was also of my mother. It looked just like Martha, and I always thought it was her.

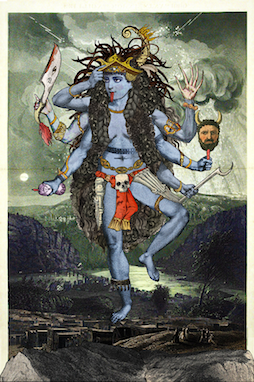

Oh, here’s Kali:

Kali Ma by John Clowder

See the devil mask?

When I was a kid, I had a mask in my room. Balinese. My mother bought it for me. Here it is:

The mask is a little bigger than a child’s face. My wife keeps it hidden in a drawer, with other witchy relics from my childhood (a carving of a snake and five skulls, photos cut up by family members, bell bottom toddler pants, etc.).

I know there’s a bit of clown in me, but I don’t think I have quite as much as Manson, Beausoleil or Waters. When I have illogical fantasies about Leslie, I imagine I am the type of man she would have settled on. Beausoleil, if he hadn’t murdered someone (and so ineptly), might well have grown into something relatively “normal,” or at least, “stable.” When Leslie was thirty-two, in 1982, she yielded to temptation, to the hope of love, to the hope of freedom, and after an extensive correspondence, married an ex-convict named William Cywin. He hatched a harebrained scheme to break her out, and before he tried to execute it, he got caught. Leslie didn’t know anything about the plan, and severed ties with him, but that marriage has been used as evidence of her continuing bad judgment. Another clown.

During the course of my thinking about Leslie, I’ve gotten married, had two children, gotten pretty bougie, published five books, broken my skeleton to bits (with sports), gone 70% deaf, haha, which was depressing but entertaining, and overall matured as a man. Or, so I suppose. I still sometimes find myself saying, in the middle of the night, “I’m ready to die.” But I don’t mean it. I’m as happy as I’ve ever been. So I’ll think to myself that this draw to death is something that’s a part of all of us—and may be something normal, something healthy. How could we move forward, how could we walk this course, if some part of us wasn’t ready, always ready, to pitch our boot over the edge of the fresh cut ground?

***

I remember, in graduate school, there was a pretty blonde woman who was diagnosed with cancer. She was a few years older than me, maybe twenty-five (I was twenty-one). She had fine straight hair and translucent skin and blue eyes. She wasn’t my type at all, but she also had a big sarcoma behind her sternum, and I was attracted to her. In class—it was a writing workshop—I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Sometimes I wonder about her, and then I marvel, because I find I’m still attracted to her, and then I wonder if she’s dead.

More about John Reed at http://johnreed.org