Seven years into his apprenticeship on the comic strip Tumbleweeds, adman turned cartoonist Jim Davis still wasn’t close to his dream of syndication. By 1976, he had learned how to ink backgrounds and time a gag, but his own strip, Gnorm Gnat, hadn’t gone any further than a local Indiana paper. His nonhuman protagonist was meant to ward off the controversy that Tumbleweeds’ cowboys-and-Indians premise raked in, but as one editor told him: “Bugs? Nobody can relate.”

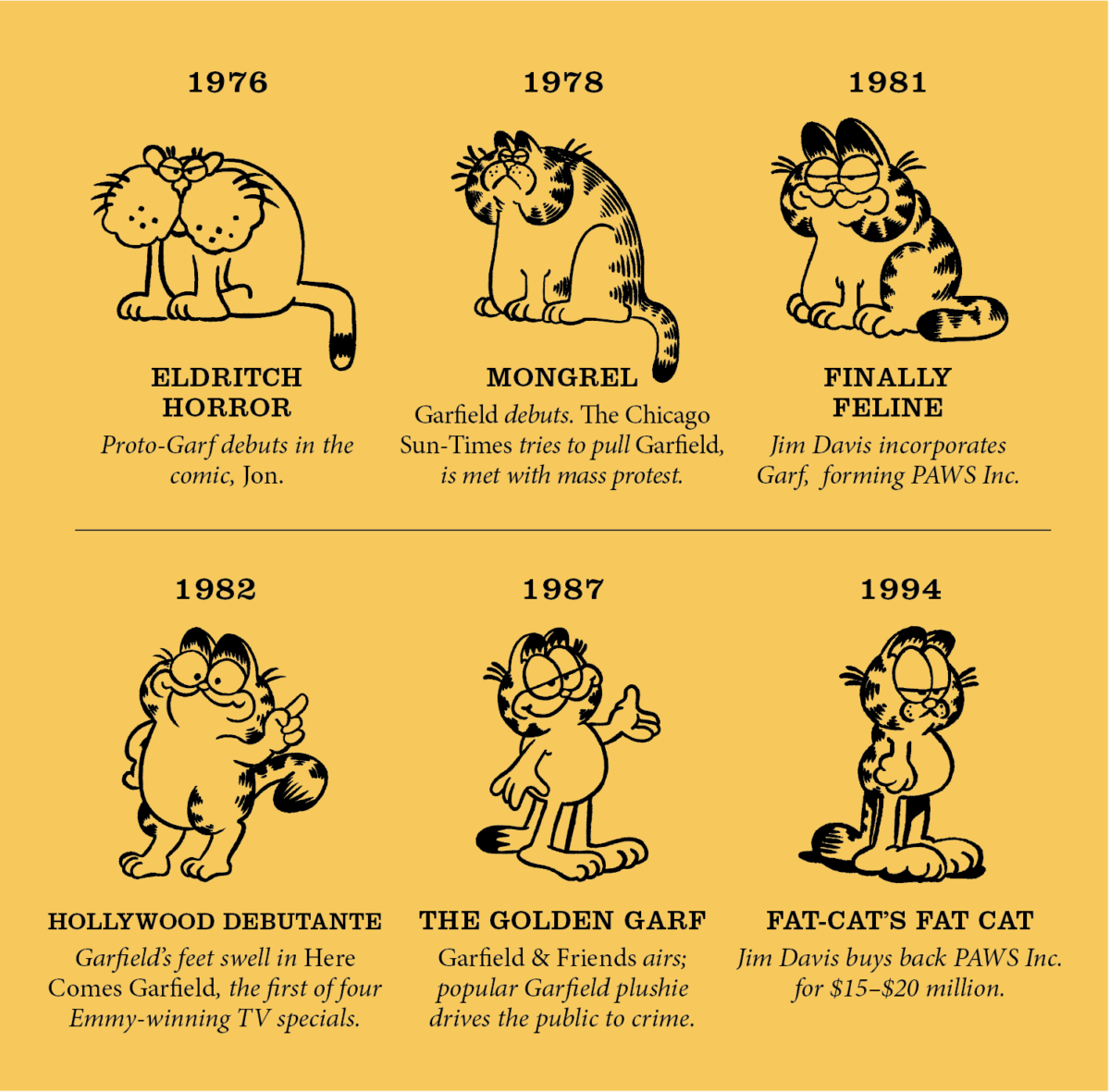

Davis pulled his comic about the smarmy, squinty-eyed gnat that year, and filled the slot with a new strip called Jon. According to one of his colleagues, Davis’s goals were modest: “All he really wanted was enough money to buy beer and cigarettes.” Loosely based on his own life, it starred cartoonist Jon Arbuckle and his hulking, jowly beast of a cat, who assumed Gnorm’s bad attitude and dour squint. Although the cat was only marginally easier on the eyes, he instantly became the star of the strip. Yet again, Davis’s strip left the pages, only to return with a new name the next year. In 1978, Garfield debuted nationally in forty-one publications, and at thirty-two years old, Davis was finally on track to creating one of the biggest comic strips of all time.

In Garfield’s first year, The Chicago Sun-Times tried to pull the comic—but was met with over a thousand protesting phone calls and hundreds of letters. Garfield’s market domination matched the cat’s personality. In a gag from the first month, Jon dangles a sausage, taunting, “Here, Garfield… Beg.” Garfield swipes at his leg and snatches the meat, chewing pensively as he thinks, “Groveling is not one of my strong suits.”

In 1981, Davis launched PAWS Inc., to handle the licensing of Garfield merchandise: the rights belonged to his syndicate, then called United Feature Syndicate, but Davis had creative control. Most cartoonists leave the merchandising to the syndicate and focus on the strip, but Davis had licensing in mind from the beginning. At the PAWS headquarters in Muncie, Indiana—the town that inspired the seminal study of Midwestern American culture, Middletown, a true American nowhere—he hired writers, artists, and other professionals to free him up to focus on the Garfield brand at large. Not that he took it easy: Davis worked sixty-hour weeks, with about a quarter of his time reserved for the strip itself.

The atmosphere at the Muncie compound resembled a modern-day tech start-up more than the home of a sleepy cartoon cat: employees clocking long hours, a product with meteoric success, and a visionary clutching the reins. “After our work during the day, Jim would buy us pizza, about five o’clock in the evening,” recalled Gary Barker, a longtime artist for the strip, of the PAWS culture in 1983. “We would work until way late, as long as we needed.” He kept a sleeping bag behind his desk.

Those hours yielded results. Garfield’s popularity skyrocketed in the ’80s. The fat cat starred in Emmy-winning prime-time TV specials, and collections of the strips in a never-before-seen horizontal format (pioneered by Davis) came out every year. One week in 1982, seven of the ten slots on The New York Times’ paperback bestseller list were Garfield titles, a feat that made publishing history. The same year, Garf even graced the cover of People, crowding out news about Christie Brinkley and the Eagles. In 1983, a Garfield balloon debuted at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, the biggest parade balloon ever by volume, according to Davis.

The strip matured along with the business. Peripheral figures, like Jon’s roommate Lyman, and wacky environments were less common, but the gags and character dynamics were still fresh. A gag might begin in the land of giant breakfasts, but Garfield always woke up in his familiar cat bed. Heavy merchandising fueled both the firm and its fandom. In 1987, PAWS introduced suction-pawed Garfield plushies for car windows. After selling 225 million in two years, PAWS pulled them from shelves, as they had become so popular that people were starting to break into cars to steal the plushies—only the plushies. But theft was a secondary concern: Davis stated that his biggest fear was overexposure.

The next year, Garfield and Friends began airing on Saturday mornings on CBS. Garfield’s design had become sleeker to meet the technical challenges of his earlier animated specials, physical changes that seeped back into the strip. After there was some trouble animating Garfield’s walk for the Here Comes Garfield special (1982), no less an expert than Peanuts creator Charles Schulz stepped in and drew Garfield with human-sized feet. Davis took the tip to heart: by the end of the decade, Garfield was a full-time bipedal in the strip, and a much slimmer one at that.

Garfield was now an economic force. Davis employed around fifty full-timers in Muncie, and personally earned about thirty million dollars a year, enough for all the beer and cigarettes he could want.

Davis was preoccupied by more than just paw size, however. He knew the world (and thus the market) was changing, and was determined to adapt. In the mid-’80s, everyone on staff was given a computer and ordered to learn how to “do email.” In the early ’90s, PAWS adopted the very first version of Photoshop. And in 1994, Davis made comics history with an unprecedented move: for somewhere between fifteen and twenty million dollars, he bought back the rights to his own comic strip. As the new millennium neared, Davis sensed that changes would come to the medium. In 1998, he predicted that in a decade or two, “the newspaper as we know it is going to evolve into something in the electronic environment. Young people are more comfortable staring at a computer screen or video monitor than they are at a piece of newsprint. That’s the reality of the day.”

Garfield was already well-suited for the internet: it was relatable on the most basic level (this cat loves food and hates work!), visually iconic, and culturally nonspecific. Nonspecific in all ways, really: when Davis’s comment about Garfield having no race, nationality, or gender in a 2014 Mental Floss interview was dug up in 2017, a fierce Wikipedia war was waged over the cat’s official gender. Someone with a congressional IP address weighed in.[1] Garfield, with its predictable timing, broad audience, and vast archives, was fertile material to be reimagined without having to keep the market in mind. In 1996, the strip went online, and fans, tired of the usual gags and armed with newfangled photo-editing software, started remixing.

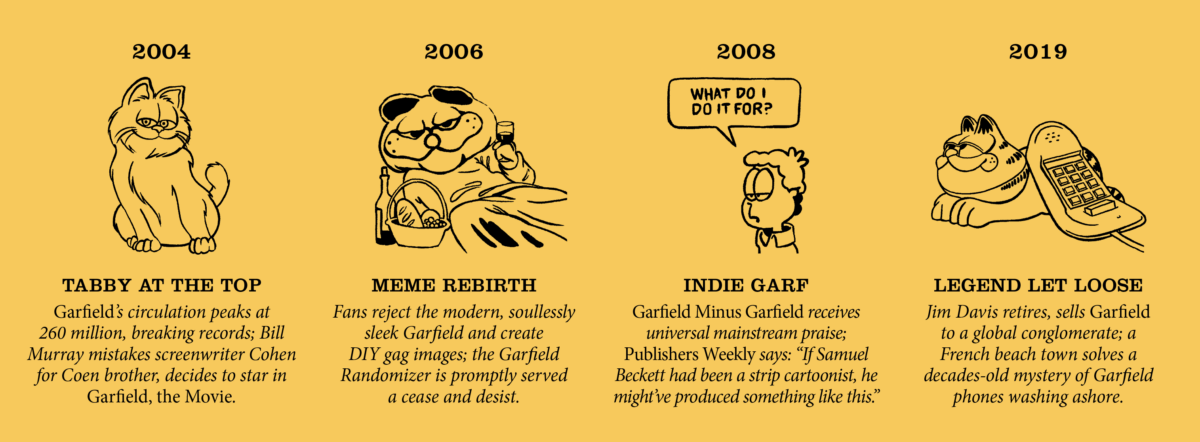

Recontextualized comics were a phenomenon that had existed even before the internet—in zines, where elements of comics that people were bored with were swapped out for fans’ (or haters’) own material. The Dysfunctional Family Circus was a fan creation that gave Bil Keane’s deeply trad midcentury comic, The Family Circus, new and foul captions. David Malki, creator of the webcomic Wondermark, discussed the phenomenon in a 2006 blog post: the paradox, he wrote, is that the more well known the original product is, “the riper a fruit it is for subversion.” By the early aughts, nothing on the comics page was riper than Garfield. In 2002, it had entered the Guinness World Records as the most syndicated comic strip ever. At its peak, in 2004, the comic reached 2,600 daily papers and 260 million readers—if the math checks out, about 4 percent of the world’s population. Yearly profits were somewhere in the ballpark of a billion dollars, easily clearing the total GDP of several small countries. But while the strip kept growing, many complained that its glory days were long over.

Enter the Garfield Randomizer, a script that pulled three random panels from the depths of the online Garfield archives and threw them into a single strip. It was funny when it didn’t make sense, but even funnier when it did: Jon smugly saying, “Cheer up, Garfield”; Garfield raising a paw in defiance; Garfield slapping Jon in circles. The Garfield formula was so exacting and narrow that the Randomizer produced plausible results while bringing back the surreal edge found in the earlier comics. Davis has been open about keeping the backgrounds nondescript (despite a whiff of the American Midwest) so that readers around the world can relate, and about perfecting the strip’s rhythm. Malki noted: “The unanimous sentiment online was that for the first time in years, Garfield was funny again.”

Alas, within months, PAWS issued a cease and desist order, and the Randomizer project was shuttered—although the creator posted the code, which may be how copycat sites exist to this day. The most surprising element of this corporate backlash is that it seems to be the first and last time that PAWS cracked down on internet fandom. Malki addressed the corporate owner directly in a post: “Learn to recognize a compliment. We like your stuff. It has meaning to us, both as individuals and as a culture. We grew up with your characters, and so they have an emotional resonance for us that overflows with potential. Let them come out and play with us.”

They did. Garfield variants proliferated in peace: Realfield (Garfield replaced by a real cat); Garkov (Garfield strips generated by text-predicting Markov chains fed by the archive); Barfield (don’t ask). By 2008, PAWS was singing a different tune. When Davis and Ballantine, the publisher of all PAWS books, got wind of a Garfield variant that was taking off, they turned the content into an official Garfield book, with commentary from Davis and Dan Walsh, the variant’s creator.

This was, of course, Garfield Minus Garfield, the best-known Garfield remix to date. Walsh simply erased Garfield from the strip, exposing Jon as a depressed guy in the suburbs talking to himself. It was a hit on campus; perhaps the 2008 financial crisis made this kind of misery resonate with young millennials.

These early variants, and the leniency about intellectual property, laid the groundwork for today’s flourishing Garfield meme culture. After the Garfield Randomizer came Lasagna Cat, a 2007 YouTube series staging absurdly high-quality live-action Garfield gags; Garfielf (2013), a deliberately low-quality animation of Garfield; and ImsorryJon, the absurd/creepy punch line for a swath of horror-themed memes in the late 2010s that started with a 2013 comic in which Garfield eats the house with Jon inside. After ImsorryJon came… Lasagna Cat, again? After a decade’s hiatus, it returned with a bang: a one-shot monologue about the brilliance of the surreal 1978 strip in which Garfield puffs on Jon’s stolen pipe, set to Philip Glass’s score to the film Kundun.

There have been countless viral Garfield memes over the last two decades, each trying to outdo its predecessor’s absurdity. Straightforward derision in the aughts yielded to ironic fandom in the 2010s, which has turned into sincere stanning, flaws and all. The Garfield meme page @garfigment was created in June 2022 and quickly amassed eleven thousand followers, of whom about 60 percent are aged eighteen to twenty-four. (Some fan accounts, like @everydaygarfield, have hundreds of thousands of followers; more niche, chattier ones hover in the tens of thousands.) Vincent, the twenty-five-year-old account owner, described their fan base: “A large portion of the fans really are nostalgic for the old comics. [They like] how you can just have fun with them and make them into what you want.” Vincent described a strip from the ’70s that includes the lines “My uncle Barney went to the vet once. He came back as my aunt Bernice.” Someone had dug up the strip and tacked on another panel with some new Garf commentary: “Trans fucking rights babey.”

The early permissiveness that PAWS showed to online creators allowed a deluge of Garfield fan content to populate the internet, which is now constantly being rediscovered and remixed yet again in the era of stan accounts and social media archiving. It’s easier than ever for young people to be exposed to Garfield, through memes or vintage merch, which has taken on a charming or cursed quality, depending on the item. (Lava lamp? Fuzzy toilet seat cover?) Garfield remixing continues offline, too, thanks to the artists who turn out their own takes on Garfield in the form of fan comics, art zines, and even tattoo designs. Tiny Splendor, a small publishing collective in California, put out a 2021 fanzine of “Garfield-induced” content called Garfield & Friends, home to the smutty comics, alternate Garf-verses, and melancholy pandemic musings of sixty-four artists. According to Sanaa Khan, who spearheaded the project, everyone she contacted “turned out to be a secret Garfield fan.” It features Louise Leong’s guide to drawing our hero (with expressions ranging from “wonky” to “so fucking bored”), Robin Milliken’s geometric abstraction “Rare Checkered Floors,” and a spare, introspective riff by Jaakko Pallasvuo: “You didn’t want to be Garfield anymore… you wanted to write poetry.” Themes include Garfield going through a breakup; Garfield breaking up with you; drugs; femme and/or goth Garf-sonas; superhero Garf; depression; full-frontal Garf; rim jobs; and the hundreds of Garf phones that have been washing up on a French beach for three decades—a mystery finally solved by the 2019 discovery of a hidden shipwreck.

Other artist-fans I spoke to consistently cited the weirder, less popular Garfield media as inspiration, like the book Garfield: His 9 Lives, a 1984 collection that experiments with different art styles and darker themes—much darker themes. The book is off-brand enough that it earned a 2011 Family Guy shout-out, in which Peter Griffin asks: “Why did you do Garfield: His 9 Lives, Jim Davis? Why did you do that dark, freaky one where Garfield kills that old woman?” (One of the vignettes in the book suggests that Garfield’s hatred of the vet stems from his past life as a tortured lab cat.) Amy Beardemphl, a graphic designer in Seattle, is a fan; in her free time, she draws Sad Cat, starring a burping, alcoholic Garf, reimagined as a depressed former child star bickering with TV’s Alf at the bar. These “copyright infringement comics” have been published in underground zines in Seattle, New York, and Quebec. Even though Garfield was built to reach the widest-possible audience, the smaller successes seem to have secured a cult legacy of their own.

Few media empires are able to attract mainstream and indie fandom. Naomi Fry, a lifelong fan and New Yorker staff writer, believes that creatives are drawn to Garfield’s passive defiance, which she describes as “the attitude of a critic,” and integral to her childhood. “Garfield is ultimately a cynical commentator with some remnant of hope within him,” she mused, “and if you’re talking about creative people, or people who are still trying to do something in the world, you want to believe that what you’re saying matters, while at the same time knowing it probably doesn’t really matter. It’s also a kind of deniability! You don’t want to come out stupid. I think a lot of people are careful about putting themselves out on the line, because there are so many ways in which you can be humiliated, especially now, when everything is public.”

The official Garfield brand continues to expand in the twenty-first century, but the newer media doesn’t receive the same kind of love. The 2000s movies Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties and Garfield: The Movie raked in cash and critical lashings alike; the many mobile Garfield games surpassed thirty million downloads in 2014, with negligible cultural impact. And after a career fighting for control of his strip, Davis is loosening the reins in his mid-seventies: in 2019, he sold the Garfield property to what is now Paramount Global (Nickelodeon’s parent) for an undisclosed sum. The company immediately announced a new video game series, a TV show, and a movie. (Online, fans are already bemoaning the upcoming 2024 Garfield movie, bewildered by Chris Pratt’s role as Garfield.) The only part Davis held on to was the strip itself, “the thing that gets me out of bed every morning.”

In a series of 1989 Halloween strips, Garfield wakes up in an alternate dimension: dark, askew, and uninhabited. He’s cursed to live on without his caretaker in a universe unlike anything he’s ever known, and he finds it unbearable, retreating to his imagination to reunite with Jon and Odie—and so the strip continues as normal. The omniscient narrator (unique in the canon) intones: “After years of taking life for granted, Garfield is shaken by a horrifying vision of the inevitable process called ‘time.’” Outside the strip, Garfield faces a similarly ravaged landscape today, as newspapers slash their funny pages to compete with the internet. But due in part to Davis’s market clairvoyance, time has been kinder to the gluttonous feline himself, who may end up being the last great face of the funnies. Davis may be winding down, but his creation seems to have found the secret of eternal life, thanks to media monoliths and online fanatics alike. Garfield’s fate brings to mind the last line from “Space Cat,” the ninth of His 9 Lives: “I’m a hero, and heroes don’t die.”

*

[1] It wasn’t Garfield’s first time in Congress: in 2003, Mike Pence wished happy birthday on the House floor to his state’s most famous feline.