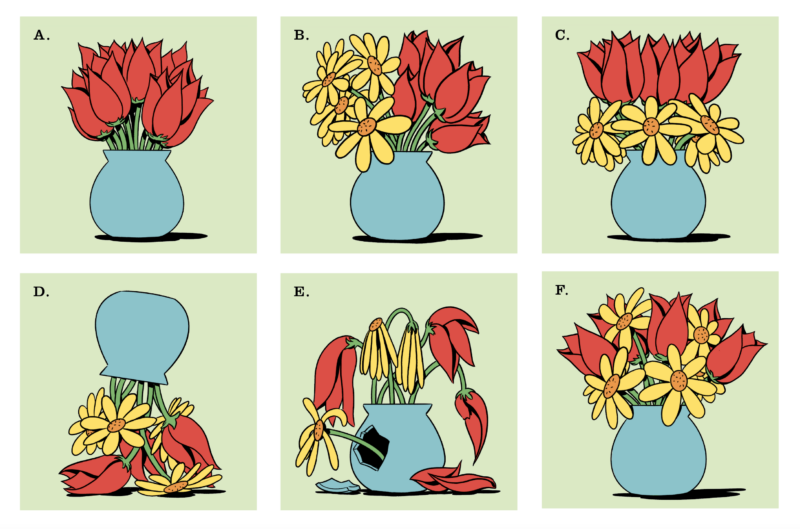

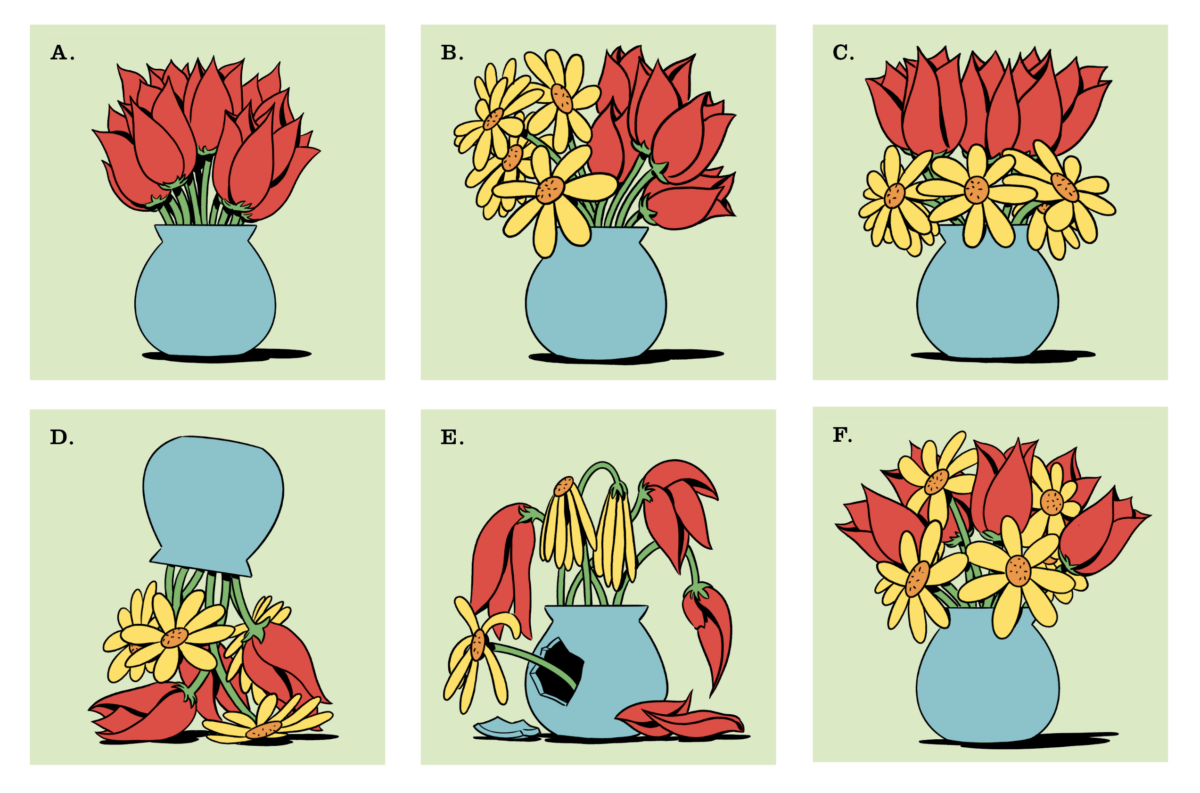

My grandmother’s advice: after you’ve put on your jewelry, remove one piece. Similarly, there are those who approach flower arranging by plunging an enormous bouquet into a big vase—undoubtedly impressive—then pulling out the heavy-headed peony, or the show-stealing rose, along with all but one stem of fern. Maybe every stem.

Less is not necessarily more. A perfect arrangement of anything is subjective. You can turn the vase this way and that. Your inclination may be to vary the different flowers, or to separate them into several vases, but if you take the one-vase approach, you probably won’t immerse the daisies in a clump, then group all the roses next to them. I know that some people hold the view that flower arrangements depend on the culture that inspired them, or admire or dislike the way flowers are presented because they express a new trend: obviously, the display sends one message when it looks one way, and carries different connotations when differently arranged.

When composing, certain short-story writers use the method of subtraction. I used to encourage beginning writers to make a messy rough draft, because when Flannery O’Connor wrote in one of her essays that you have to put something there before you can take it away, she meant exactly that: you have to do it before you can omit it. I go for rough-draft clutter because when I look at the typed word moon, that word might lead me to realize that there’s a good reason to have my story begin in moonlight. Thinking in the abstract about the moon wouldn’t have led me anywhere. What you don’t need can be highlighted and deleted (the moon’s waning, under your fingertips). Then you might ask yourself why a ladder leans against the house. And on it goes.

There are innumerable variations of how an individual story might be constructed. Sometimes those alterations bring a character into the foreground; other times, a character can recede so deeply, he/she might just disappear. (This was what my husband did in high school when he was forced to play softball: he’d be assigned to right field, where he’d slowly back into the woods behind the playing field, continuing to inch backward until he was obscured by the trees, then walk home.) Some of my characters have done the same thing to me, cleverly retreating. Others, who wouldn’t shut up and always threatened to steal the show, got their way, even if I later deleted the whole story.

Writers have a love-hate relationship with characters who take on a life of their own. How will the writer prevail, amid scene-stealers? One obvious answer is: So what if you intended something? What might be gained, at least for a while, by following an uncertain path, an unknown plot?

I say this as Deep Background, and also to make quick remarks about a story’s beginning, as opposed to my real subject, its end, after which comes (if the writer is lucky) a second ending: the story’s placement in a book.

To varying degrees, writers wrestle with their characters, as the characters simultaneously wrestle one another. Sometimes it’s as if a wrestling mat has been spread out, and the competitors have to work it out down there: the writer isn’t even the referee; it’s the writer who must adjust, not the characters. Similarly, as Raymond Carver wrote in his essay “Fires”: “Somehow, when we weren’t looking, the children had got into the driver’s seat. As crazy as it sounds now, they held the reins, and the whip. We simply could not have anticipated anything like what was happening to us.” This situation wasn’t unique to the Carvers. They let the kids intimidate them because they felt overwhelmed, tired, or confused (psychologists give advice about how to deal with this dynamic all the time), but about the Carvers’ children, I have to ask: Why should they behave better than fictional characters? Consider the number of times Carver admitted to being surprised by things that seemingly happened outside of his control in his writing. He quotes Flannery O’Connor, saying about her story “Good Country People” that “I didn’t know there was going to be a PhD with a wooden leg in it. I merely found myself one morning writing a description of two women I knew something about, and before I realized it, I had equipped one of them with a daughter with a wooden leg. I brought in the Bible salesman, but… I didn’t know he was going to steal that wooden leg until ten or twelve lines before he did it, but when I found out that this was what was going to happen, I realized that it was inevitable.” Carver was relieved to read this, because he thought it was his “secret” that he, too, composed this way. As many writers do. I’d say this is usual. Maybe not infallible as a writing method, but often the default position: in relinquishing power, the writer might gain a story.

But let’s say that however the writer was overwhelmed, or left sitting comfortably, consulting notes for how the personalities and events in the story would emerge, ultimately a story came to exist, and if and when the writer was satisfied, there it was: it could continue on its trajectory into the world, sometimes in a magazine or literary quarterly, other times not, but held on to. What are writers to do with many of these successful stories, except aspire to give them continued life by collecting them in a book they hope will be accepted for publication?

The question then becomes how to arrange that book. What do you do if you have half a dozen stories, including one that’s thorny and wickedly funny, another that has a golden center but is otherwise dreary, one whose narrator speaks tongue-in-cheek, another told from a dog’s point of view? (As an aside: I remain particularly pleased by my story “The Debt,” in which a dog who, as a puppy, was thrown out of a car window but lived, interrupts the present-day story to make remarks about its rescuer—a character who we already know is, in other matters, really a piece of work.) Back to what I was saying: I’m thinking that those hypothetical, dissimilar stories I’ve conjured up might be a first collection, unless the writer is a very protean writer indeed—though, to state the obvious, the majority of story collections are written by people who’ve attended an MFA program, so they might have understood their mandate from the first, about focusing on a theme or one character, whether they wanted to hear that or not.

In 2023, publishers want “related” stories. For example, ones with a consistent character who moves through them. Publishers also feel impelled to gain wider readership by labeling obviously related stories “A novel in stories.” Or, in some cases, they simply assert that the tenuously connected stories constitute a novel. The novel is more than a reassuring touchstone; it’s a kind of unmovable boulder, somewhat related to a concept the French have, which is to call memoirs novels. If your first book is a story collection rather than a novel, you’ll be lucky—perhaps even so lucky that you have a two-book contract, and your stories are already written and the novel isn’t, so that the stories are intended as your introduction as a writer, an early glimpse of your sensibility, as if writers are analogous to the lucky piece of turquoise a gambler touches for good luck before placing her bet. Or they’re published because of overwhelming enthusiasm in spite of being stories, or for many other noble reasons.

Sometimes it will turn out that writers were wrong, and novels actually become their optimal genre. Other times, when a writer has written only one book, they can’t be expected to know what they’ll eventually write. I don’t know if Grace Paley aspired to write a novel (or even if pressure was put on her to do so), but I never heard her say she did. (She never wrote a novel.) There are, of course, quite a few examples of short-story writers who’ve never published a novel, including one of the best short-story writers ever, Deborah Eisenberg. (Read “Twilight of the Superheroes.” Why would she need to write a novel? This rhetorical question is also often asked about Alice Munro’s transcendent late stories.) Raymond Carver never wrote a novel, even when his children were grown, and he had the money to eat, and he wasn’t trying to write—of course, in longhand—during work breaks, sitting in his car, those times when he had a few moments off from janitorial work, or the sawmill. When he became very ill, he wished to exclusively write poetry. I knew the short-story writer Peter Taylor, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his short novel A Summons to Memphis (one of only three he ever wrote, over his long career). He was as bemused as he was appreciative, saying that “they” must have just wanted him to have it. He knew the genre on which his reputation justifiably rested.

It’s hard to generalize (and rarely helpful), but at least in first assembling one’s stories as a collection, writers will probably stick to their original concept of how the reader should best come to know the characters: for example, James Joyce writing about people living in the small town of Dublin pre-1914. What troubles writers, it seems to me, is a question no different from one we consciously or unconsciously pose to ourselves that isn’t restricted to writing: whether first impressions really are hugely important, even to the point of being indelible. We’ve learned from Malcolm Gladwell that people’s impressions are formed frighteningly quickly, so, really, it might not be the best idea, if you’re thinking about a logical order for your stories, to have an otherwise truly intriguing character kick things off by telling a stupid joke.

There’s a kind of double burden in a story collection, because those who first appear, even when they become invisible later on, continue to tinge the stories that follow. So: think of your favorite short-story collection, and say which story comes first. Personally, I couldn’t tell you this about any of my collections. I’ve certainly placed a story first with conviction, only to move it elsewhere, because, though I didn’t want to omit it, it was wearing too much jewelry.

Who’s to judge? The counterargument is that more can be better. My friend Liz wore forty silver bangles on her wrist. Janis Joplin never gave restraint a second thought. Though I’ve read Dubliners innumerable times, I don’t remember which story comes first—or where stories are in anybody else’s book. I can say which were my favorites, and I have that weird reader’s ability to visualize where something is on a page, but not where in the book it’s to be found. I’ll know that a sentence by James Salter I want to read again (who wouldn’t?) is on the right-hand page, two-thirds of the way down, near, but not exactly at, the end of a paragraph—but in which story? I can rarely zero in on it. I guess I do remember that Deborah Eisenberg’s Twilight of the Superheroes begins with the title story, because I used to teach it, and I didn’t have to flip through the pages to find it. (Some people demagnetize watches; my Post-it notes come unstuck.) “Midair” by Frank Conroy, from the book of the same title? Somewhere in there. It would be interesting to know where Alice Munro placed her title stories, those times when she had one, and if that varied by book. No doubt her editor Ann Close could say immediately, but I can’t. I should also factor in that there are people who don’t read from first to last. My brilliant friend Michael Silverblatt (of KCRW’s Bookworm) once told me, in passing, that he first approached a book as a physical object; he’d hold it and think about it, then decide to read a bit of the last story, or even the book’s final sentence (my god!), because getting a feel for the book was a way to enter into it. (He sometimes speaks reverentially about aspects of a book, from the typeface, to the paper, to the cover’s embossed lettering—but it’s just something he notes for himself. To Michael, a book is a tactile undertaking, as well as his opportunity to explore its contents.)

Since I’m so interested in how writers figure out an order in which to present their collections, why don’t I retain that knowledge? I think, in part, because I’m a reader, definitely not of the Michael Silverblatt sort. (I’m too inhibited; he’s at ease with books. He does a pas de deux with them, even when they’re near strangers.) As for the title story becoming the book’s title, I often agree with what the writer has separated out for special notice, but not always. Sometimes, although writers have the “right” title for an individual story (I used to happily let Roger Angell, or other friends, title my stories), one story’s title is often not expansive enough to apply to the whole collection. As we all know, there’s also marketing: it’s not apocryphal that Grace Paley’s Enormous Changes at the Last Minute was often shelved in “Psychology.” Such things are to be worried about.

In 1976, when my stories were first published as a book (Distortions contained nineteen stories, which by current standards is ridiculous), the collection didn’t have to have a theme, and the stories didn’t have to be related. I chose the ones I liked best, of the ones I’d written during the previous few years, and my agent submitted the book to publishers. Even then, they were pretty much the also-rans. I mean, I’d have—I was lucky to have—a two-book contract, and the other book had to be a novel (if you can believe it, there was a time, pre-memoir, and certainly no one had any reason to think I could write nonfiction then, including me). Rather than imposing a theme, all I had to do was some weeding, without any seeding. I like to think I was good at this—meaning, hard on myself. Certainly other people, in and outside of publishing, were an enormous help (“Oh, that story. Leave it out”). The order of the stories didn’t have to do with a trajectory, or with the stories’ interdependence: they were just there, like a box of chocolates: there was no reason the Madagascar vanilla buttercream should be next to the lemon verbena lavender-infused shortcake heart. There was likely to be a description of the chocolates inside the box (brilliant English majors are still often recruited for such jobs), so you could avoid eating a very delicate chocolate right after eating one with an intense chocolate taste that would overwhelm it, or you could simply try something and see if the flavors clashed. Obviously, the candy descriptions had to be enticing, brief, and to the metaphoric point. While I suppose a similar little brochure could be included with a story collection (“Sweetly funny, with hints of salt and anomie”), short stories are already over-described. That’s what reviewers do; they summarize them (at least in paraphrase; paraphrase makes everything strange), describing their inventive, unexpected, shocking plots. Books could come wrapped in paper, tied with ribbon, with cholesterol warnings rather than spoiler alerts… but enough. Sequestering during COVID was hard on me, as it was for many, many others.

That said, I’ve done something you won’t be surprised to hear about. I’ve written a book containing six related stories. Let me qualify: related, but deliberately not interwoven. All the stories in Onlookers take place in the same Southern town, in approximately the same time, and involve characters who have a passing acquaintance with one another, or cross paths, but don’t know one other well. They might live in the same building; a character might see the doctor of the first story exiting a food store (a real one) that my characters favor, but that’s that. One character might visit another in a nursing home, but she’ll be a relative’s friend, not their own. I had fun going back into a story that had a short scene in which perfunctorily well-mannered middle-aged and elderly people eat together at a restaurant, and interjecting an opinionated, outspoken, though definitely not entirely wrong female doctor who is very upset and wants to stir things up. That happens in the first story in the book—I brought in a nonbeliever, an antagonist. Later, she appears in another story I’d written earlier, though I decided to place that story later in the book. In it, she’s even angrier, provocative, and certainly not entirely wrong. She’s a minor character, yet she speaks to an undercurrent in the first story that shakes up everything pleasantly banal that the characters have been agreeing about, exposing them, letting the reader know that someone is sounding an objection to life lived conveniently on the surface. You go, Bronwyn! What a pleasure to “develop” her in terms of a consistent trait (her big mouth), then later to place her in a situation that alters her life, so that while the anger remains a constant, it changes, and is there for a more personal reason.

When I began writing Onlookers, I wasn’t thinking of a group of related stories. One of the stories was written nearly two years before the others, and the first and final stories were both written last, to bracket the book, once I realized what I’d been doing. (I admit: I sent it to my agent with eight, not six, stories. Her assistant, Mina, and she and her daughter Priscilla Gilman, who’s also a writer and an amazing reader, independently felt that two of the stories should go. They were right—then the book was on track without two good stories that were also digressions. Thank you, Lynn, Mina, and Priscilla.) Also, the last story deliberately presents an inherent kind of digression, not only of character, but of milieu, though it turned out I was right about a previously mentioned minor character: he’d been waiting patiently for me to get to him. It had been my instinct that the final story should contain a different tone, rather than being smoothly incorporated into the collection. Energetic, too-talkative George could easily sustain it. Without him, that story’s other character, Stacey, the empathetic head nurse where he works, could never have been revealed. It seemed to work to bring in the “wrong” character, in a collection focused on people and things that are never quite right for many different reasons. Loquacious yet rather inarticulate George became a different version of Bronwyn (whom he doesn’t know; I couldn’t have put those two together, because George operates on instinct, and would have walked out on her), yet Stacey’s fondness for him, and what he provides her with, define her, and she’s the one whose imagining ends the book. If she (if it) lifts off, it’s all due to George.

There are many eminently sensible ways to end a book. When I asked Don Lee—whose shapely yet seemingly loosely held collection The Partition really impressed me—how and why he’d ended with the amazing three-story cycle, he gave me some background information: He’d written “The Sanno” as a stand-alone story, but because he’d flashed forward in it, he decided to write a second story about his character Alain (“Reenactments”). Then he realized he’d have to write a third: “I liked the idea of covering one character’s life over forty-five years, especially as a parallel to the title novella in my first collection, Yellow, which had followed a character from adolescence to middle age. With both collections, it made sense to me to end with the longest piece of the cycle. Otherwise you run the risk of alienating readers if they aren’t drawn to the long work, whereas if you begin with some unrelated stories, they can quickly turn to the next story if the first doesn’t grab them.” (This, from a person who worked as a brilliant story editor, as well as being a writer. I’d say that Don has a heightened awareness about how many readers read story collections.)

As for my late friend Peter Taylor, he was asked in 1987 (the year he won the Pulitzer) how he’d like to be remembered. Answer: “I would like to have as many of my stories as possible survive and be read and liked.” Maybe it went without saying that now people would take note of his having won the Pulitzer, but I think he meant what he said: read the stories, please. (He took a little distance from himself as he continued: “At my age it’s hard not to want to feel that your last book is your best book.”)

Maybe where a writer ends a collection depends on their temperament, as well. Joyce knew, after he’d written Dubliners, that the book needed one more story to complete it, and he made it a difficult one, a far-reaching story that was obviously rooted in things he wanted to say about Dublin (and Ireland). “The Dead” became the final exploration, and the ultimate purpose, of the book. It also happens to be the most magnificent story. (Elsewhere, he wasn’t going for magnificence.) I don’t think he was so much pulling out all the stops as making the reader pause to see that he knew them. It’s a story that makes you rethink all the others, which is a hard thing to do. In many story collections I admire—whether the heart-stopping story comes first, last, or in the middle—the ordering has been thought out, even if it misfires. If there’s a Collected Stories, writers do have a chance to take the obvious approach, and reprint them chronologically (which might take into consideration when they were written, rather than when they were published). I think writers are very aware of how they’ve changed; it’s just that they might have doubts about whether that change is necessarily good—as Peter Taylor hints. But with a first collection being published now, well: if the stories are mix-and-match, the writer will probably either not get published, or will have to make concessions. Is it depressing or painfully consoling that the publication of Dubliners was delayed by Grant Richards, the London publisher, for seven or eight years because of concerns about how certain things Joyce included might be upsetting to Dublin’s inhabitants? (Imagine Dubliners with trigger warnings.)

Onlookers is my ninth collection (tenth, if you count The New Yorker Stories), but I caved: related stories. Though it wasn’t as painful as I thought, because the book’s variations on a theme snuck up on me, somewhat the same way Don Lee’s first Alain story led him onward to the others: my six stories involve the taking down of Charlottesville, Virginia’s Confederate statues, though I didn’t write about a rally I didn’t attend (I’d moved). What I did try to address was the covert or unmeasurable effect this debate—and of course the horrifying rally of August 2017—had on different characters during a similar time period. In some stories, the statues are still in place; in others they’re gone. As I wrote, some of them truly disappeared overnight; I have photographs of others in various stages preceding their exit, with graffiti sprayed on their bases, or plastic netting barriers built around them. And, along with Robert E. Lee sitting atop Traveller, the monuments vary: also removed was a statue of Lewis and Clark with Sacagawea, a subject that’s revisited from story to story. Regardless of differing opinions, it was deemed necessary to get rid of the towering male explorers and the subservient woman over whom they tower, while other characters explain in a vexed way that of course she was kneeling: she was a guide! A guide would look at tracks. Nevertheless, the debate and the solution regarding the highly contested statues became a constant refrain. These issues were there, even when they weren’t talked about, even when Bronwyn wasn’t raging. COVID, too, got into the book because there it suddenly was, a reality. Nothing I’d set up had been quickly or easily solved (if it is, why write?), but I kept feeling that one additional perspective—a personal vision—was needed. I think that would have gotten lost if I’d placed it earlier. But it’s certainly a different book if, because of its length, the reader doesn’t read the final story. It’s the reader’s loss if they have the same attitude about the Alain stories that end Don Lee’s book, and it’s just unthinkable that someone might pick up Dubliners and stop after reading the next-to-last story, and think, I get it. That’s enough.

Read to the end, please! Ask yourself why the writer chose to end on that note rather than another. Then reconsider the collection from the writer’s perspective as well as your own. If the writer’s guessed right, you can feel their presence hovering, taking a motionless bow, silently speaking to the work’s subtext, maybe, or even turning a little mean, provocative. Writers can keep themselves out of a book for only so long, and the final words of their final story often give a huge hint about what was at stake all along. Of course, as is true of “The Dead,” whatever you read is likely to be O so eloquently expressed—one final revelation, one final wager.