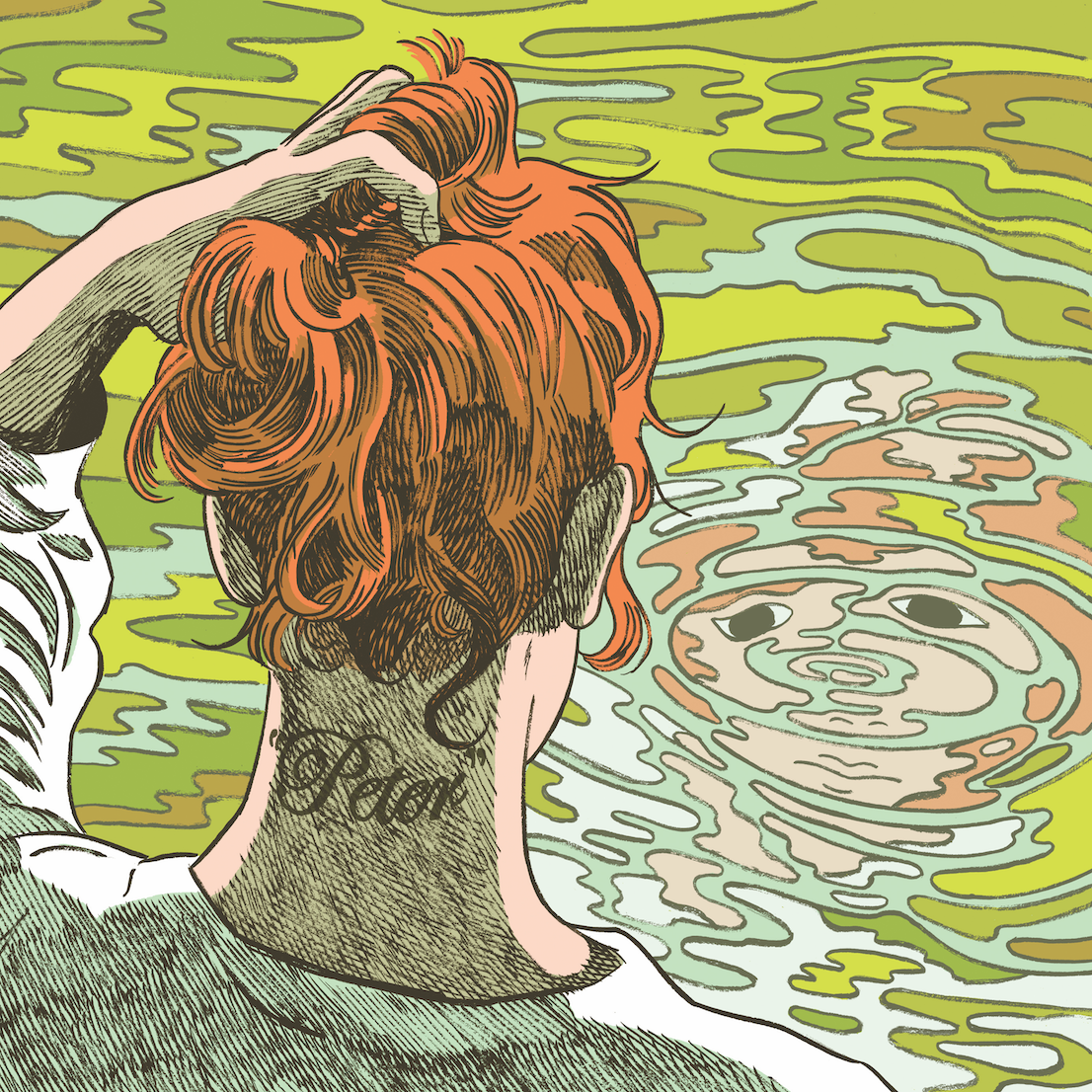

A shock survivor I knew years ago—an activist I’d flown out West to meet because I was writing a profile of her—showed me a tattoo she had on the back of her neck. She turned away from me, on the bench where we were sitting, on the balcony of a tree house overlooking a river. She lifted her red hair to reveal the tattoo, which said “peter” (quotation marks included). She had tattooed the word there to remind herself of her own story, which made me think of Memento. “Peter” was something that had been said to her by Jesus himself. It had helped her to finally escape from the hospitals and the doctors and the shock.

“Sixty-six rounds,” she’d often tell me, repeating that number. Sixty-six rounds of electroshock. Sixty-six was the figure she had tabulated, based on her medical records—at least the parts of her records she was later able to retrieve. But like her memory, the paper trail of what she underwent is spotty. She shared lots with me; my inbox was sometimes flooded with emails from her, each with PDFs attached. When I visited her at home, she’d show me boxes of files. She would have been consulting them, as a way to brush up on her own story prior to our conversations, like a student cramming before a final—a futile exercise, because her short-term memory, like her long-term memory, was now pretty shot.

I asked her that day at the tree house by the river what actual memories of her life she did have—of her childhood, for example.

At this she squinted. Like I’d asked her something challenging.

She produced a couple of recollections of her youth. But mostly, she explained, she didn’t remember her life. She didn’t remember her sons’ birthdays. She didn’t remember much of her marriages. She didn’t remember much of her career; for decades, she had been a nurse.

She shared one of the memories she still had from all those years she’d spent nursing, of a time when a small plane crashed near the ER where she was working, and they were slammed. She’d had a patient that night, a boy who’d lost a parent, and she still thinks of him whenever she smells gasoline.

Despite the huge gaps in her memory, it’s clear how much she had loved the work, that big bloody ballet. When some catastrophe came flying through those doors, everybody had a role; everybody was there to help. My sense is that she had stuck with the anti-shock activism for so long because she had worked in health care. She still had a nurse’s morality. She was a believer in medicine. Shock therefore incensed her.

She’s long since stopped practicing; subsequent to the treatments and their aftermath, she realized she couldn’t safely work. But her former profession seemed to linger around her still, like an afterglow. I’d noticed the easy way her tongue had with medical jargon and dosages. Or how she took my hand, noticed my blue nail beds, and wondered aloud if I had a syndrome called Raynaud’s. Her experience as a nurse also helped her, I think, when it came to trying to piece together her own story by retrieving her medical records, and when it came to presenting her case to legal professionals, the media, or anyone else who was willing to listen.

It’s a tricky matter, though: how to tell your own story when you don’t remember it. Like most self-identified “electroshock survivors,” the former nurse especially couldn’t remember the period during which she would have supposedly consented to the treatments, though in her case she doesn’t feel she was in a condition to consent, given the combination and volume of psychiatric medications she was then on. Her story, which I came to know well, contains many difficult aspects, ones that made her a less-than-ideal focus of a work of journalism (or legal case).

It had always been a tough sell, a mere reported piece about electroshock. But once I had actually placed it, to an outlet that had at first been enthused, I found that my editor kept watering it down further and further, in terms of how straightforwardly I could talk about the science, let alone about the everything else—the political situation, I suppose. My editor kept asking for more of the other side, the pro-shock side. I’d alternate between explaining that I couldn’t stretch my own facts further than what my years of reporting had yielded, and trying nonetheless to comply.

Eventually, I became exasperated, worried I’d insult the survivors who had given me so much of their time—especially the nurse, but also all those who’d shared their miserable tales with me, sometimes at great length and despite great difficulty. Which also includes my late uncle Bob, about whom I wrote my first book. Bob was psychiatrically hospitalized as a teenager and probably electroshocked. I say “probably” because, while there’s evidence he was shocked, he didn’t mention this having occurred, perhaps because he didn’t remember. His stepmother, however, recalled that he’d been shocked in a state hospital.

When I was writing the book about him, which took eight years, I’d mostly avoided investigating electroshock itself. The subject intimidated me too much, or squicked me out. But after the book was done, perhaps feeling guilty, I began trying to better understand what was really going on with electroshock (or ECT, electroconvulsive therapy, as it’s called by the medical establishment nowadays). After I’d found and begun interviewing that former nurse out West, she passed along word to other survivors that there was finally a reporter willing to talk to them. For a while, they were contacting me all the time, and all the time I was interviewing shock survivors.

I don’t know if they remember me, but I remember them.

There was the man in his seventies who was institutionalized and shocked as a teenager, while his mother was dying of cancer. It was the bad old days—no anesthesia—and with every round, he felt intensely that he was dying; he’d thought about the experience every day since. He became a psychologist himself but was, when I first interviewed him, still closeted personally and professionally about what he’d survived. There was the man in Connecticut who’d been shocked against his will—and his family’s will—forced by a court order to undergo ECT after he’d permanently damaged both his legs trying to kill himself. There was the special-education teacher in the Midwest who, after the treatments, couldn’t remember what she did for a living, let alone that she had a master’s degree. She’d once received a greeting card from a stranger; she later figured out they were actually a colleague. There was the man in his twenties who, after treatment, couldn’t drive his car or tie his shoes. He explained the shame of that: having to ask his father for help tying his shoes. He’d had a high IQ in high school, he said. There was the woman who’d been shocked after her boyfriend was killed in an accident. She had debated agreeing to an interview, she admitted to me, because what was the point? She couldn’t remember an estimated 70 percent of her life. Her doctors had told her there was nothing they could do for her. Many of the survivors had heard: your memories will return. When the memories didn’t, they heard: there’s nothing that can be done.

That day by the river, the nurse explained that she’d probably forget me and our interview by the time she went to bed that night. This degree of memory loss was common for her. She told me how she’d leave a therapy appointment, and by the time she reached the parking lot, she’d have forgotten most of what was just discussed. For a while after her treatment, she’d volunteered at an elementary school, trying to get some basics back, like the elementary-level times tables.

Now, many years later, I’ve fact-checked her account and those of the other survivors I spoke with. Most of them tended to feel that their story wouldn’t matter, that nobody would ever listen to them. They often discussed, in detail, the medical situation, and the broader social situations, in which they found themselves. I also interviewed, at length, the professionals who ally themselves with the shock survivors, from psychiatrists to psychologists to attorneys, and I read endlessly: the books, the research. In my experience, shock survivors, like psychiatric survivors more generally, tend to have an accurate sense of what’s up.

Many of the shock survivors made a point during our conversations of mentioning the cultural figure who, to them, is their most famous example: Ernest Hemingway. They’d ask if I knew about Hemingway, and were pleased when I replied yes.

Hemingway received multiple rounds of shock at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, in 1961. He wrote to his biographer that the treatments had ruined his career, because he couldn’t remember anything anymore, and his memory had been his fodder. No longer could he remember his great mess of a life, all his adventures in Europe, in Africa, in Cuba. No longer could he remember the hunting, the fishing, the women, the wars. He couldn’t remember, therefore, he couldn’t write, therefore, he wanted to die.

“It was a brilliant cure,” Hemingway wrote of shock, “but we lost the patient.”

Soon after, he rose one morning, careful to not stir his wife, donned his favorite, bright red robe, retrieved a gun, and standing in his Idaho foyer, shot himself through the skull.

Then there is the public, who tend not to know about any of this. In a Family Feud–style board on Hemingway, for example, one would think of so much, his suicide included, before one would think of electroshock. Now, having read many more Hemingway biographies than I ever expected to, I can confirm that the shock part is true. Papa’s biographers, however, do not tend to highlight the role that it might have played in his demise, the way shock survivors do. Survivors tend to emphasize what Hemingway himself said. The survivors know that people tend to discredit the words of shock survivors. They know their problem, really, is an information problem.

When the public thinks of shock, they tend to think of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. But before they were “shock survivors,” the shock survivors themselves were members of the public. So they, too, had tended to think of Cuckoo’s Nest, of Jack Nicholson, whenever their providers brought up ECT.

Maybe you, too, think of Cuckoo’s Nest. Of Nicholson biting down on the mouth guard, the “little dab’ll do ya” of jelly on his temple. The white-gauzed electrodes touched to his skull and bam, the electricity hits. Maybe we remember his grimacing mug, the camera lingering a little too long, the white-uniformed staff holding down his seizing frame. Maybe we remember the end of the movie, when he’s turned into a vegetable by the next even-more-severe-seeming psychiatric intervention, a lobotomy. Or we remember when Chief Bromden then puts him out of his misery, which the audience is meant to view less as a murder and more as a compassionate assisted suicide.

Maybe because Cuckoo’s Nest is an old movie (1975) and an even older book (1962), a lot of people assume electroshock must be a thing of the past, a bygone treatment. Not only is this not true, it is perhaps just the opposite: ECT appears to be only increasing in popularity in America (at least given the admittedly not-great data that is available). Journalists such as myself run into an immediate problem when discussing ECT: the scientific record on it is pretty useless. For much of its history, hardly anyone in a position of authority was keeping track of things that would seem to be quite obvious to quantify, like: How many people receive ECT, and at what rate? How many people are injured by and/or die subsequent to receiving ECT? In the last few years, a number of new studies have been published on ECT, but there nonetheless remains a lack of research on vital questions like the extent to which ECT harms and even kills people.

I feel it’s important to dwell for a moment on the science, its imperfect record notwithstanding, because there have been efforts to know what can be known about ECT. One British academic psychologist who’s focused on this, Dr. John Read, has performed reviews of recent scientific literature on ECT, meaning he’s evaluated the meta-analyses and determined what the record has shown. Having spoken with him and read his work and that of others engaged in similar efforts, I can tell you, in brief, that what we know about electroshock is overwhelmingly grim. It therefore becomes hard to write a piece about ECT that doesn’t seem to question what some readers will doubtless feel has been a useful medical intervention for themselves or a loved one.

Available evidence supports the opinion, however, that these treatments essentially cause brain trauma, however severe. The impact of electricity to the frontal lobes is hard to predict, in part because patients receive different amounts of electricity and in different sequences. Therefore, ECT is a bit of a game of roulette: Some patients do feel ECT has helped them or even saved their life or that of someone they love. (For the record, I believe such people, too.) Some patients do not experience adverse effects. Others are moderately to severely harmed. People do die subsequent to ECT, though at what rate it is impossible, at present, to accurately know. Again, one cannot know exactly how common the use of ECT even is, though it appears to have become more popular for American hospitals to invest in ECT clinics in recent years.

The medical explanation for why patients tend to be prescribed multiple rounds of ECT is because the apparent beneficial effect of the treatment has always been observed to be temporary. Meaning, for the severely depressed patient, for example, who feels a lift after a round of ECT, that effect tends to fade. To shock’s opponents, this is easily explained by the fact that a frequent temporary side effect of brain trauma is euphoria.

Typically, an ECT patient receives multiple rounds of treatments, once a week or more, over a period of time, for weeks or months. Some patients return routinely for periodic “maintenance,” as did the actress Carrie Fisher. Fisher was an avowed fan of shock until her death at age sixty.

Fisher’s book Shockaholic is ostensibly a love letter to ECT, albeit a complicated one. In it, Fisher bemoans how ECT was eating her memory, such that she couldn’t remember vocabulary words, or having dinner with a friend the previous week. Fisher was also, like so many ECT patients, a consumer of multiple psychiatric medications, which, along with ECT, she credits with saving her from alcoholism and debilitating depression.

In her book, Fisher provides some history of shock, albeit the history one tends to encounter if one googles about it some. You’ll read that shock was developed in the ’30s, but that it’s come a long way since the bad old days. It’s true, in a sense, that ECT today is less gruesome than it was in decades past, especially before patients were anesthetized prior to treatments. Back then they were not administered muscle relaxers, and would sometimes break bones, especially in their legs and back. Before mouth guards, patients would often bite their tongue.

The point of ECT, or electroconvulsive therapy, has always ostensibly been to induce a seizure in the patient. It was once hypothesized that a patient could not have both schizophrenia and epilepsy, therefore inducing the latter in the form of seizures may somehow cancel out the former; this notion ultimately had no basis in reality. Shock itself, however, stuck around. It stuck around and it found more and more applications. Today, the clinical focus of ECT has shifted to patients with severe depression, often the sort of depression that has been re-labeled as “treatment-resistant depression,” meaning that multiple drugs have been tried and found not to work. The posture of the pro-ECT establishment, at least today, tends to be that ECT is a method of last resort, used for the very suicidal. However, while it is difficult to know, it is certainly possible that suicide rates might actually increase for ECT patients. And, as one survivor activist who keeps close tabs on all this has pointed out to me, “The FDA has no recorded research validating the claim that ECT prevents suicide.”

But in the popular imagination, the point of shock has never been the seizure. Pop-cultural depictions of shock tend not to show the seizure part at all, with a few exceptions, like in Cuckoo’s Nest, or in Showtime’s Homeland (often cited in medical literature for its general accuracy). Depictions of shock tend to focus on its other, more controversial reality: namely, that electricity to the skull induces brain trauma and therefore memory loss, and can have other negative effects.

Psychiatric researchers have studied how Hollywood fails to accurately portray ECT and the effect of these representations upon patient attitudes. Their papers tend to fault fictionalized versions of shock for being outdated—for showing ECT patients who do not receive anesthesia, for example.

The authors of such papers, however, cannot seem to grapple with these larger questions, like: What if ECT itself is the problem, not just Hollywood’s portrayal of it? What if, amid the greater informational void surrounding shock, its cultural depictions—these movies and TV shows and books—however ill informed, happen to sometimes say the quiet part out loud? Within these texts, I believe, one senses the reverberations of a crisis that has yet to be fully acknowledged by the medical establishment. For this reason, they bear close inspection.

Often our cultural portrayals of shock depict it as literal torture. Shock is a mainstay of horror and its ilk, shown in the Chucky franchise, and in American Horror Story: Asylum, and in The Exorcist III. It’s used to gruesome effect during the ending of Requiem for a Dream, when Ellen Burstyn’s character repeatedly receives ECT—heavily medicated, although not given anesthesia and therefore conscious and in apparent agony—while the film’s strings score swells. In the third season of the Star Wars series The Mandalorian, a character has his memory forcibly erased with a futuristic, ECT-like “Mind Flayer” machine. Shock is sometimes used as a punch line in bro-y bits where brain trauma is the joke, as in the Rick Moranis flick Strange Brew, or in an episode of Mike Judge’s Beavis and Butthead, where Beavis and Butthead shock their “nads” and cause a town-wide power outage.

But especially common in Hollywood’s depictions of shock is the idea that it can be used to brainwash an individual, especially with evil intent. In the 2016 movie Suicide Squad, the Joker creates his sidekick—his former psychiatrist and sometime romantic partner, Harley Quinn—using electroshock, while laughing and screaming (here the technology is apparently able to produce the effect of making one into a horny, violent clown). In The Manchurian Candidate from 2004, with Denzel Washington and Meryl Streep, Washington’s character is repeatedly electroshocked. It’s suggested that he is first shocked as a method of brainwashing during the Gulf War. Later, he receives ECT as a means of memory restoration, miraculously unscrambling his prior programming.

Arguably the most famous electroshock survivor in our current popcultural landscape is Captain America’s best friend, Bucky Barnes, a.k.a. the Winter Soldier. Initially presented as a strapping American lad heading off to World War II in his soldier suit, Barnes is captured by bad guys who brainwash him using electroshock and Russian trigger words, turning him into a nefarious hitman. Thus he remains for decades. By the time he runs back into his former best friend Steve Rogers, Barnes has become the Winter Soldier: He has a powerful metal arm, long, stringy hair, and an occasional smoky eye. He doesn’t remember his old buddy at all, apparently because of the electroshock. Slowly, over the course of many movies, Rogers helps Barnes remember him, rekindling their friendship and bringing him back around to the good side.

Bucky Barnes’s story contains the ultimate fantasy of actual shock survivors: full recovery. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Barnes makes his way to Wakanda, where, with the assistance of vastly superior technologymagic, he is cured. In The Falcon and the Winter Soldier TV series, he is now living somewhat of a normal life, or trying to. He’s cut his long hair. He’s in court-mandated therapy. He’s also sleeping badly, having flashbacks, now having to confront his extra-long lifetime of extra-terrible memories.

Throughout Hollywood’s depictions of shock as torture, there is a particular current of anxiety to do with shock being used to control women. In the 2004 remake of The Stepford Wives, the plot culminates in the discovery of a secret medical facility within the town’s men’s club, wherein women are implanted with electrical devices to control them—a sci-fi imagination of an ECT-like technology.

The movie opens, however, seemingly in another lifetime, in which Nicole Kidman’s character is an executive at a major television network. While onstage presenting her new, aggressively feminist lineup, an enraged former reality show contestant (Mike White) attempts to shoot her. While recovering from this near murder, she is then subjected to ECT.

We re-meet her in a hospital suite full of flowers. She apparently has no idea who she is or what’s happened. Her husband, played by Matthew Broderick, drives her and their kids to Stepford, Connecticut, where he’s already purchased them an obscene mansion. She arrives in Stepford, silent. She wears dark colors and sunglasses.

Glenn Close (as their real estate agent) is initially dismayed by her appearance, until Matthew Broderick cheerfully explains about the ECT.

“Hello, little energizer,” Glenn Close replies. Later on, Nicole Kidman complains to her new friends in town lightheartedly that her doctor thought she “needed enough electricity to light up Vegas.”

In 2022’s Don’t Worry Darling, electroshock again comes up as part of a more elaborate female-control scheme. It’s ultimately revealed that Harry Styles’s character has kidnapped his own partner and held her hostage, placing her in a 1950s-skewed computergenerated fantasy. In this world, the women of one picture-perfect, gated desert community spend all day vacuuming and preparing roasts, and then forget to eat said roasts because they’re too busy fucking their husbands on the dining room table. Florence Pugh, playing Styles’ wife, slowly becomes more aware of something amiss in her world, in part because of the black-and-white flashbacks she keeps having to what is revealed to be electroshock treatment, which she’s seemingly forced to undergo once more by the men.

After returning home, she forgets a neighbor’s name. “My head’s been a bit of a blur since the treatment,” she explains to a friend.

“It’s OK. It’ll all come back to you,” her friend replies.

The viewer later realizes that that friend, played by the film’s director, Olivia Wilde, was in on the men’s scheme, abetting them in holding all the other women hostage. We’re shown a grimy Harry Styles in the real world, outside of the computer-generated fantasy, eating tuna fish from the can by the kitchen sink. He then gets back in bed alongside his imprisoned partner, donning the Clockwork Orange–style eyewear that transports him into the simulation. In her former life, Pugh’s character was a busy physician. We see her trembling eyes. We feel her humanity.

One can imagine, perhaps, the appeal of the fantasy of selectively targeting traumatic memories and erasing them. Michel Gondry’s masterful 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind portrays the sci-fi notion of damaging the brain so as to specifically erase the memory of one’s ex. The basic idea is echoed in the titular track of Ariana Grande’s new album Eternal Sunshine (“So I try to wipe my mind / just so I feel less insane”). In the music video for another song on the album, “we can’t be friends (wait for your love),” Grande sits in a retrofuturist mind-sweeping suite, wearing super cool single-eye makeup and knee-high boots, while her mind is wiped of her ex, even as she weeps and tries to stop the procedure. Eventually, she acquiesces, happily replacing him with false memories of instead loving a dog.

In Gondry’s film, the A-plot involves Kate Winslet and Jim Carrey deleting each other from their lives—or trying to. Jim Carrey’s character asks his mind-erasing doctor, played by Tom Wilkinson, if there’s a risk of brain damage. Wilkinson dryly explains, “Well, technically speaking, the operation is brain damage.” He adds, “But it’s on a par with a night of heavy drinking. Nothing you’ll miss.”

The B-plot has to do with the staff at the mind-erasing doctor’s office, namely the on-again, off-again romance between Wilkinson and his employee played by Kirsten Dunst. Toward the end of the film, it’s revealed that Kristen Dunst’s character—whose palpable crush on her boss is quite apparent—was, unbeknownst to herself, already involved with the doctor and had her memory wiped. His wife (Deirdre O’Connell) catches them as they reignite their affair, and in a magnificent moment says, just before driving off, “Don’t be a monster, Howard. Tell the poor girl.”

In Eternal Sunshine, men repeatedly use mind erasure to dupe women they covet sexually. Tom Wilkinson’s character has evidently refused to stop working with Dunst’s character, his former affair partner, even though he’s gone so far as to erase her mind. Her coworker (Mark Ruffalo) attempts to take advantage of her ignorance of her own situation as he also tries to sleep with her. We also see Kate Winslet’s character being conned into a relationship by another of the clinic’s staff, played by a super slimy Elijah Wood, because he knows her circumstances and has her ex’s discarded mementos.

I’ve often contemplated the real-life relationship between shock and feminism. Several times, years ago, I interviewed Dr. Bonnie Burstow, a late feminist professor and psychotherapist in Toronto who was a longtime, vocal opponent of shock. She understood shock to be a key feminist issue, plain and simple, right up there with abortion and equal pay.

This was because of the data. For its whole history, shock has been administered disproportionately to women. Two-thirds of shock patients are women, though that fraction is possibly higher. These days, your quintessential American ECT patient is a woman over fifty with insurance, experts told me. Female ECT patients have reported their husbands consenting to the procedure on their behalf, as well as outright coercion. As Dr. Burstow said to me once, “I don’t think people care about women’s brains.”

Perhaps my favorite terrible example of shock in pop culture—because of its sheer ahistoricism but also its aspect of feminist revenge—is the 2014 horror flick Amnesiac, starring Kate Bosworth. Her character monologues a history of electroshock to the man she’s strapped to a bed and is torturing: “Electroconvulsive therapy,” she explains, “dates back to the sixteenth century in Eastern Europe.” (Which to me is just incredible, considering that the technology of electrical power as we know it is more or less an advent of the twentieth century, but anyway.) Shock “really gained popularity in the United States in the 1930s,” she goes on, saying that although the treatments are “controversial,” they are still used for depression.

“I think this will help you, honey,” she says, turning on the machine. “I really do.”

L’elettroshock was first attempted on a human subject in 1938, in Mussolini’s Italy. Two psychiatrists at the University of Rome were presented with a man whom they diagnosed with schizophrenia; he had been scooped up at a train station by police, and, as one of the psychiatrists observed, didn’t “appear to be in full possession of his mental faculties.” The doctors’ theory was that schizophrenia might be cured by having seizures. Until then, they’d been experimenting on pigs. They now hooked the man up to their machine.

At first, they shocked him, but not enough to induce a seizure; eventually, they did trigger one. He is said to have cried out in agony, begging them not to shock him anymore, saying that he would die. The psychiatrists, pleased to have produced the seizure, heralded their machine a success.

The technology quickly spread across the Continent and to the States. By the 1940s, nearly half of public psychiatric institutions had adopted the use of electroshock machines. This was despite there still having been no research as to whether these machines were safe or effective. When that research did begin, ten years later, studies showed that ECT was ineffective at treating schizophrenia and depression—although it did accelerate senile dementia in older patients.

What these machines did produce were patients who were more compliant, less likely to put up a fuss in increasingly crowded and under-funded public hospital wards. Like the more extreme lobotomy, shock rendered patients docile, which to hospital staff could be seen as a positive. All this was presented as treatment, of course: as help.

Nurse Ratched, in Kesey’s Cuckoo’s Nest, speaks this doublespeak fluently. She first broaches the notion that it might be “beneficial” for the character of Randle McMurphy to receive shock therapy, “unless he realizes his mistakes.” In the world of the book, which was informed by Kesey’s time working in a state psychiatric hospital, there is no misunderstanding what shock is and what it’s for. As fellow patient Harding explains to McMurphy:

That’s the Shock Shop I was telling you about sometime back, my friend, the EST, Electro-Shock Therapy. Those fortunate souls in there are being given a free trip to the moon. No, on second thought, it isn’t completely free. You pay for the service with brain cells instead of money, and everyone has simply billions of brain cells on deposit. You won’t miss a few.

Speaking of doublespeak, perhaps the urtext that depicts electroshock being used as torture and mind control is 1984, released only a decade after the technology’s advent. In George Orwell’s novel, the protagonist, Winston Smith, is eventually seized by the authoritarian state, imprisoned, starved, tortured, beaten, and forced into all manner of false confessions. Throughout, however, he maintains some private dignity: his love for his partner, Julia, for example, and his hatred of his captors and their figurehead, Big Brother. Arguably, Winston’s eventual demise pivots in part—as the plot of Cuckoo’s Nest also pivots—on the employment of electroshock. After receiving the treatment, Smith is slowly reduced to what the party wants him to be: a gin-swilling cog who loves no one except maybe himself and Big Brother.

1984 is a warning, an imagining of a future dystopia. In this world, the masses are sedated with sports, porn, pop music, and news of perpetual foreign wars, and are unaware of the machinations of the totalitarian authority that is governing them. Orwell envisioned a society full of screens and surveillance supporting a vast policing and prison system, one where at any moment you could be grabbed by the state and detained and drugged and forced to undergo electroshock, potentially becoming forever altered.

This is more or less an accurate picture of America today, especially for those who are deemed severely mentally ill. An American with that type of diagnosis can be effectively condemned to a secondary class, legally speaking, entitled to many fewer rights and liberties than other citizens. That psychiatric patients experience all this is a reality that the public became slightly more aware of after the 2021 emancipation of one very famous sometime psychiatric patient, Britney Spears.

The fact is that today, plenty of people take psych meds or undergo ECT because they are compelled to—if not by pressure from their families or doctors, then because they are forced to by the state. Especially upsetting to anti-shock activists is that coercive ECT remains legal. Also horrifying is the fact that ECT is still used on populations who cannot legally consent, like children, people with developmental disabilities, and elders with dementia.

The one context in which the wider public has seemingly grown wary of shock itself is in regard to “conversion therapy”—as in anti-gay or, increasingly nowadays, anti-trans conversion. Indeed, when it comes to media coverage of conversion therapy, the barbarity of shock tends to be understood as a given, at least in outlets that recognize the humanity of us trans and queer folk. Not incidentally, I’d add, since the 1970s these identities have been more or less de-pathologized by the psychiatric establishment (though for trans people, our health care remains extremely gate-kept and, of course, is now under attack).

When it comes to “conversion therapy,” cultural depictions of electroshock plainly understand it to be torture, as mere punishment of the deviant. On HBO’s otherwise pretty stellar series Barry, one of the weakest plotlines, I’d argue, involves a vengeful ex-wife who kidnaps her gay husband and attempts to make him straight using electroshock. In an absurd DIY play on exposure therapy, perhaps, she forces him to watch a man dancing in a jock strap while pushing the voltage of the old-fashioned shock machine strapped to his head higher and higher.

Sometimes on TV, as here, shock looks cartoonishly evil. You’ll see the repeated trope of the shock practitioner cackling as they say, “More” or “Again,” shocking someone a second or third time. Shock machines themselves often look antiquated, even in contemporary contexts, as with the Barry example. Sometimes they resemble their close cousin the electric chair. On the TV show Alias, Jennifer Garner’s character is tortured using an old-fashioned shock machine in a very run-down facility in Bucharest, Romania. At one point she’s submerged in a filled bathtub before she is supposed to be shocked, but somehow the machine doesn’t electrocute her.

I recall a Halloween years ago, when, walking down a Brooklyn sidewalk I came upon an elaborate display that included a life-size figure in gray sweatpants, strapped to an electric chair, being shocked repeatedly in the skull. I wondered for a moment whether it was electroshock or an electric chair. Then I realized that perhaps in our cultural imagination, they are the same.

Again it frustrates the psychiatric establishment that pop culture gets this all so wrong. It’s unthinkable, to this camp, that anyone would question the clear, lifesaving utility of ECT. Some years ago, I turned towards various groups that are theoretically in charge, trying to gain some clarity. I was in touch with representatives at the FDA. I attended an American Psychiatric Association (APA) convention with a press badge. At the APA convention’s big pharmaceutical fair, I stumbled upon the booth for one of the two ECT machine manufacturers, which happened at that moment to be empty. It contained a backdrop with the slogan “Automated. Easy. Fast.” and a photo of the psychiatrist who’d started the company embracing one of his machines. Through the years I have tried to contact the manufacturers for interviews, most recently via email (for this story, both manufacturers were contacted in this manner and given an opportunity to respond). One has never responded; another answered my most recent email request and, during a subsequent exchange, I outlined this essay’s main points and asked if they had any comment, especially when it came to the treatment’s safety and efficacy. “As with any medical treatment or pharmaceutical,” the company’s president wrote, “there are side effects to ECT and we are very open about those on our website and in the Patients and Families Booklet that is sent out with each of our devices.” They said the way I described ECT in my letter “is not entirely accurate.” I asked them to clarify what the inaccuracies were, but they did not respond further.

Though there have been a number of lawsuits attempted against the manufacturers through the years, back in 2017, I was following along when a particularly promising-seeming suit was filed by a law group in California. Among the folks who pay close attention to this issue who I was communicating with at the time, there was a feeling that legal progress was being made. The case was, in fact, inspired by the nurse I’d interviewed out West, by her efforts to get some lawyers interested in ECT. That anybody in the anti-shock camp felt hopeful about anything seemed to me rare indeed. That case—which was against the company that didn’t respond for comment on this story—was settled right before it was due to go to trial, and the results were in favor of the plaintiffs (though there was no admission of wrongdoing on the part of the company). Following this ruling, however, that ECT manufacturer added a very small but very significant phrase to its machine’s long list of potential side effects: “brain damage.” This wording was quickly softened to “brain injury.”

Soon after, right around Christmas 2018, the FDA issued a press release: there had been a ruling about ECT. Prior to this, for decades the FDA had declined to weigh in on whether ECT was safe and effective in treating any psychiatric disorder. Now it was finally doing so, to an extent. It had changed the classification of ECT machines to Class II devices, which indicates “moderate risk.” Since the 1970s, when our first applicable consumer protection laws were passed, the treatment had been classified as Class III, which indicated the highest risk. ECT machines received this classification and were permitted to go on not because treatments were considered safe and effective, but because they were already in use.

Ever since, the FDA had ostensibly been waiting on the two ECT machine manufacturers to supply research showing that their products worked and were safe. These companies do not appear to conduct research themselves (though the manufacturer who did respond to me wrote that it does donate its own machines to be used in research and that “a vast amount of research and clinical studies have been done on ECT for the past forty years”). In any case, for decades, the regulation of electroshock never seemed to get anywhere, despite the periodic convening of FDA panels, which would then release some sort of report.

And yet now in late 2018, in the wake of “brain damage” being conceded as a side effect by one of the manufacturers, the FDA was finally issuing this ruling, reclassifying ECT as the less-risky Class II for patients diagnosed with catatonia and major depression, and saying it awaited evidence as to its safety and efficacy for other applications. One psychiatrist, a longtime shock opponent, blogged that it was now “open season” for shock patients. As Bonnie Burstow wrote me soon after: “Using terms like ‘reasonably safe and effective medical devices’ in the same breath as talking about ECT machines is double-talk at best.”

The former nurse with the tattoo on the back of her neck hadn’t known much about shock before her own sixty-six rounds, at least that was her sense. She didn’t believe that any of the hospitals where she’d worked had had ECT wards. To her, it’s obvious that electrical voltage to the head will cause brain trauma. To her, if any doctor pretends they don’t know this, they are lying (perhaps also to themselves).

She used to try so hard to get anybody to listen to her. She’d take out ads in the local alt weekly, looking for other shock survivors. She’d go around putting pamphlets under windshield wipers, even one time, when a parking lot employee was following behind her, removing each one. She’d stage protests outside the hospital where she’d gotten treatments.

In my experience, when you go to any Mad Pride protest, whether it’s specifically a shock-related one or any demonstration across from an APA convention or what have you, there are always self-identified shock survivors in the crowd. Old folks and young folks. People who were shocked a few months ago; people who were shocked a few decades ago.

Maybe because that’s who cares most about all this, ultimately. They are the ones who have had to carry on the conversation, often despite a great deal of hardship and social apathy and other factors working against them. They find one another. They congregate, in person and online. They tell their stories, or at least try to.

I recall one anti-APA demonstration some years ago across from the Javits Center on Manhattan’s West Side. A group of psychiatric survivors had gathered on a blustery spring morning. They demonstrated to nobody: to passing traffic and the few cops who stood yawning by. The survivors gave speeches into a bullhorn. One sang with a ukulele. They marched up and down the sidewalk, carrying a coffin.

They unfurled a large banner along the chain-link fence behind them, which I think they hoped the doctors high up in the convention center across the street might notice.

It read: NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US. Another slogan one sees and hears often at such protests is the doctors’ ancient credo, echoed back to them: FIRST DO NO HARM.

Globally, if you look to bodies like the UN and the WHO, for example, there is little debate that nonconsensual ECT is a violation of human rights. I’ve reported on the future of psychiatric civil rights overseas, as when I attended a World Hearing Voices Congress in The Hague. At such gatherings of psychiatric survivors and their professional allies, people frequently cite language from the UN and the WHO pertaining to coercive shock and the need for its abolition.

Some activists do feel that adults who are informed can and should have access to any available psychiatric intervention, even ECT. Others feel that shock should be outlawed altogether.

Do doctors have a responsibility to stop the use of this technology? In many other countries, this question is being considered more openly; here in America—home of the APA and its biomedical model of mental disorders—we tend to be unaware that these conversations are happening. A few years back, King’s College London hosted a prestigious public debate on shock. The statement being debated was “This house believes ECT has no place in modern medicine.”

And yet. If one day you are in a doctor’s office—maybe your own, maybe a relative’s—and you hear your best option, perhaps, at this point, is ECT, and you hear that shock isn’t like it used to be in the old days now, anymore, it’s not Cuckoo’s Nest, that it’s safe and effective for severe treatment-resistant depression, whom are you going to trust?

As one survivor I interviewed wondered aloud to me once: What would have happened if ECT had been presented accurately to her? If they’d said, nobody’s claiming to know why or how ECT actually works, and you may lose your memory, including potentially your memory of who you are, and your loved ones, and what you love to do, would she have consented?

The fact that shock may deprive you of whatever you once did with your life is rarely made clear in our portrayals of shock, Bucky Barnes being an exception. I would also cite the 2008 film Revolutionary Road (based on the 1961 novel by Richard Yates), for which Michael Shannon received a Best Supporting Actor nomination for playing a resentful shock survivor.

He has been temporarily released from a state hospital and is visiting with Kate Winslet, who’s playing an unhappy, nonconformist Connecticut housewife. Her realtor, Michael Shannon’s mother (Kathy Bates), had gratefully broached the subject of allowing him to socialize with Winslet’s family. The scenes in which the madman comes to visit are deeply uncomfortable; he often spouts off truths that the sane people around him otherwise avoid acknowledging. On a walk through the forest, Winslet’s character is sympathetic when she learns about Shannon’s plight.

“I hear you’re a mathematician,” she says.

“You hear wrong,” he retorts. “It’s all gone now.” He matter-of-factly explains about his electroshock: “It’s supposed to jolt out the emotional problems. It just jolted out the mathematics.”

“How awful,” she says.

“How awful,” he echoes her. “Why? Because mathematics is so interesting?”

Some patients do just give up: the shock survivors told me of their comrades who’d killed themselves. The former nurse out West would tell me about other survivors who were gone now, like one friend who’d been a golfer, but had stopped abruptly after his treatment. Later, his body was found on a golf course with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. I admit that, as a reporter, I haven’t ever met a group of people as generally miserable as shock survivors appeared to be—at least when it came to their daily existence, how tough it often seemed, and how lonely. And I say this as someone who’s spent much of my career interviewing psychiatric survivors, which is to say survivors of extreme trauma, as well as others who are in situations that might leave them socially isolated and/or eternally

present—folks with severe brain injuries and other cognitive disabilities, for example. I’m not the first to observe that shock survivors are especially miserable, perhaps because in our society, they aren’t even acknowledged to exist.

The only vaguely accurate portrayals of ECT itself tend to be of its use on willing and compliant patients. On Homeland, for example, the bipolar-diagnosed CIA operative protagonist (Claire Danes) undergoes ECT voluntarily. She seems to do so, however, in order to forget her affair with the terrorist she’s fallen for, images of their moments together flooding her mind as she succumbs to the anesthesia prior to convulsing.

On Six Feet Under, one of the show’s widowed matriarch’s new partners, George, depicted brilliantly by James Cromwell, is revealed to have had a trauma history and, triggered, falls into a psychotic episode. He then elects to undergo ECT treatments, which are shown to be challenging but ultimately helpful to him.

It’s the sort of nuance often lost in any conversation about shock. One of the psychiatric survivor activists I’ve come to know once expressed appreciation of that Six Feet Under story line about George—its being pro-ECT notwithstanding—because of how it endowed these topics with complexity. Viewers see George as a boy as he witnesses his alcoholic mother’s suicide, which now triggers a present-day episode.

But it is largely socially unacceptable to portray shock patients as aggrieved about what’s happened to them, however damaged they have been by it. One exception being the 2005 biblical-monster flick Constantine, in which Keanu Reeves plays the titular chain-smoking demon slayer and shock survivor with a no-fucks-given attitude. In a flashback, an overhead shot depicts Constantine receiving ECT as a teenager. “My parents were normal; they did what most parents would do,” Constantine says in a voice-over. “They made it worse.”

It’s apparent in the world of Constantine that no amount of electricity to the head is going to help you, unless your only goal is to deaden yourself inside, or literally to die. In the case of Constantine, he still sees demons, plenty. Demons are real. They’re also seen by his costar, played by Rachel Weisz, a detective whose identical twin sister committed suicide—suspiciously, they feel—in an old-fashioned-looking Los Angeles psychiatric hospital.

In a more recent Constantine television reboot, however, this apparently radical stance on ECT has been totally softened. In the series’s opening scene, an adult Constantine receives ECT, explaining: “Believe it or not, I came here voluntarily. My name is John Constantine, and I’m an exorcist. In my line of work there are days you just need to forget.”

A 60 Minutes segment from 2018 called “Is shock therapy making a comeback?” featured Anderson Cooper interviewing Kitty Dukakis—a longtime, outspoken pro-ECT patient. It showed footage of her anesthetized and receiving treatment, Cooper noting her trembling feet. Kitty is the wife of a politician whose name is less famous these days, but who remains quite famous in this niche discourse. She cowrote a 2006 book (Shock: The Healing Power of Electroconvulsive Therapy) and has often appeared in such media reports. It is usually the case, as in this 60 Minutes segment, that such media acknowledges pro-shock patients as if their point of view is novel, and at the same time ignores the existence of self-identified shock survivors and their professional allies.

Before I reached out to her, the former nurse out West had labored for years trying to get any media to pay attention to her. I once asked how many reporters she’d contacted. “Thousands,” she replied. Once or twice she’d gotten a write-up for a protest, or maybe something else would seem to be happening, but then it would fall through. After our own effort seemingly failed, she’d sometimes email me excitedly, telling me about a TV crew or an online outlet that was finally doing the big scoop.

Then I wouldn’t hear from her.

Some years ago, she shifted her strategy from the media to attorneys. For a while she mailed these binders of information she compiled about shock to law firms—all law firms, any law firms. She contacted countless attorneys, but nobody bit. Dejected, one day she finally gave up and threw everything into a dumpster. She went out and drank some wine and, passing a tarot reader, decided to stop in for a reading. The tarot reader told her to “get the papers off the floor,” which she took to mean get all the binders out of the trash and keep going. Not long after, one of her binders did catch somebody’s eye, at a law office in Sacramento. He was just an intake clerk, but he sent the information to his father, who was an attorney in Southern California.

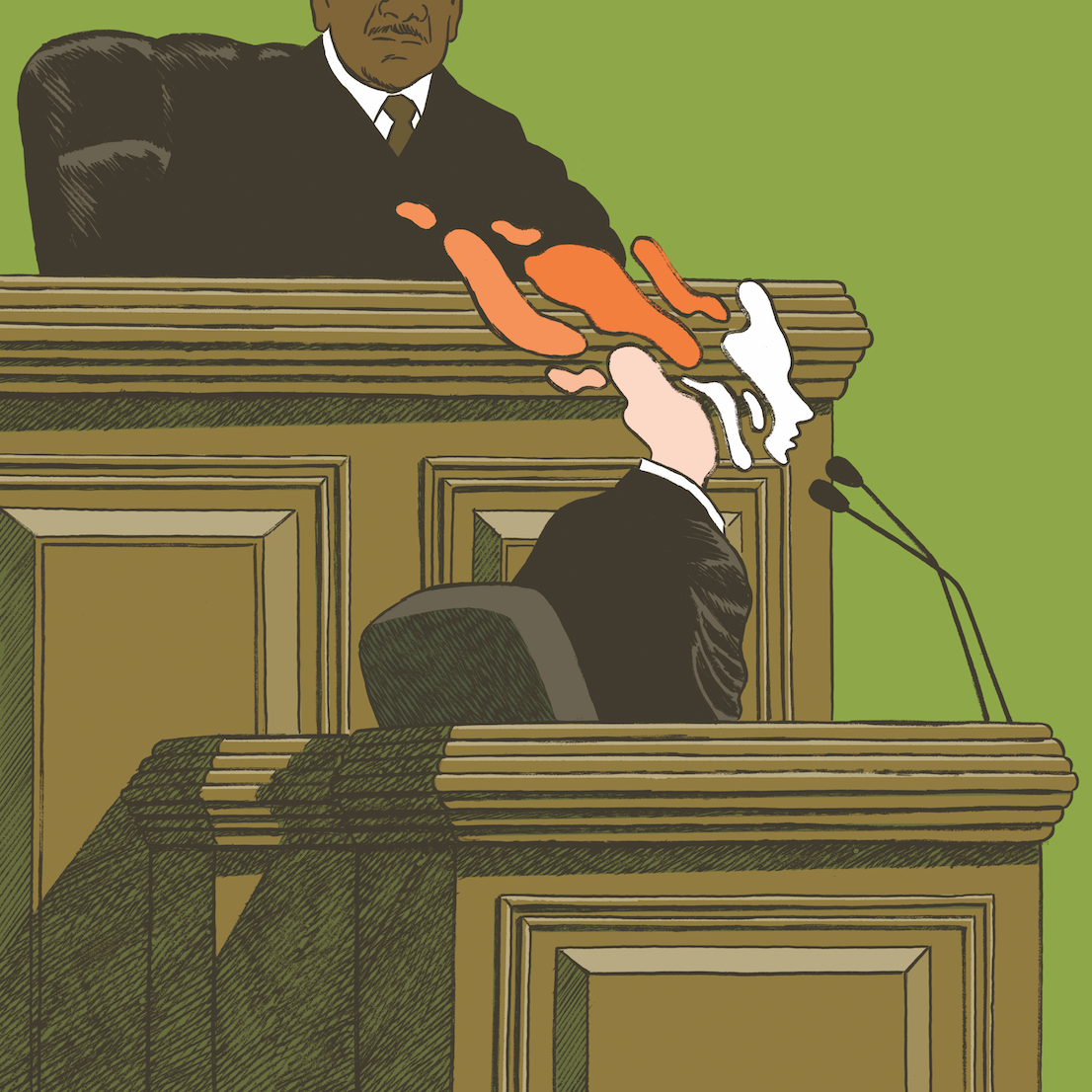

I eventually interviewed them both, the father-and-son legal duo who decided to take on the ECT machine manufacturers. The dream, I suppose, would be Erin Brockovich–but–for–shock—however, it’s very hard to sue anyone about ECT. Most survivors who claim they have been damaged—the potential plaintiffs—don’t tend to have much memory of what happened, especially of the lead-up and the treatments themselves. In the eyes of the law, or even just of a jury, such people may be deemed much less trustworthy-seeming than, say, doctors, hospitals, and corporations, who also tend to be well represented.

One of the other big hurdles, the attorney in Southern California told me, is that you cannot file a class action lawsuit if a judge doesn’t “certify” a “class,” as in, legally recognize a group of plaintiffs as a group. Unlike a group of coal miners who were injured in a single accident, or townspeople who were all poisoned by the same water supply, ECT patients are individuals who’ve received various treatments, on various schedules, from various hospitals that use machines made by one of the two different manufacturers, and so on. Determining liability in this legal context can become so challenging that the whole matter tends to get tossed out.

Individual plaintiffs do sometimes receive one-off settlements. I spoke with one of the two plaintiffs who’d received a settlement after that 2017 suit. He’d been an Ivy League–educated former bank manager. He’d had ECT after he was hospitalized for catatonia in the wake of a divorce.

He had kept a journal during that time, which is probably part of why he made for a good plaintiff. Before receiving the treatments, he’d thought ECT was a thing of the past; he’d thought of Cuckoo’s Nest. He’d been assured it wasn’t like the bad old days.

He described the treatments themselves, how they’d have you up real early, grumbly belly because you can’t eat prior to having anesthesia. They’d wheel you down into the dark guts of the hospital, put you out, and you’d wake up with the worst headache of your life. Many survivors described that, how you woke up so disoriented, dazed, and totally confused, with your head in such excruciating pain.

Despite the FDA’s reclassification of ECT, I don’t doubt that people will continue to try to protest shock; some have always tried. Since its invention, shock has always received a great deal of pushback, both from within and outside the medical establishment. When shock first arrived in America, it was decried as plainly evil by some, doctors and laypeople alike, even as it was also quickly embraced.

I’ve wanted to die, badly. I’ve had days when dying was my main thought, when not dying was my main effort. As in, I was actively battling an interior self that wanted me to jump off the balcony, now, now, or drive into that median or off that cliff, now, now. I have known such depths of depression, just to be real about that; I’ve known them since my childhood, which included a lot of severe trauma. Nowadays, I’m also someone who’s known what we’d call “psychosis.”

So, for a long time and with great interest, I’ve wondered what can be done for a head like mine. I say this not to freak you out but just to be honest about the fact that long before Uncle Bob first got me curious about this, I was somebody caught here. Caught between this life and something. Somebody who desired, deep down, a way out. Even my own death sounded better sometimes than surviving another night in my reality.

Ultimately, I have survived, the whole story of which I won’t go into here. But point being, I do know that I personally would never consent to having ECT, knowing all I do about it. I also respect if other adults would make other decisions for themselves, especially people who feel their desperation so extremely.

I will say that it does scare me that we do not let these be personal decisions, which psychiatric treatments we receive. That instead we leave these matters, this tremendous power, up to regulators, which ultimately means to individuals who are probably unaware of much that they do not feel the need to question, because the psychiatric authorities have deemed it true.

The nurse out West doesn’t remember consenting to shock, but she supposes she must have. She guesses it was because of the medication, and also because she wanted to see her children. But she doesn’t recall the sixty-six rounds themselves, or that time period. As for how she got away, this she remembers because of the tattoo on the back of her neck.

For context, she wasn’t before, and still wasn’t when we spoke, a Christian. But how she escaped was that they were shocking her and shocking her, and she really felt they wanted her to die, but then, one day, she had a vision.

In the vision, she was friends with Jesus.

They were standing together by a water’s edge.

Then Jesus addressed her as “Peter.”

“Peter,” he said. “You are a healer.”

Jesus now told her to put out her hands, and then poured gold that ran like liquid through them.

She needed to escape, Jesus said. Pack a bag, quit your meds, go to your sister’s, in Iowa. So she did. She packed a bag and quit all her meds cold turkey (except the anti-anxiety medication she knew she couldn’t just stop taking without going into serious withdrawal), and she somehow got herself to the airport, and through TSA, and to Iowa and freedom.

When she turned away from me and lifted her red hair, showing the “peter” tattoo on the back of her neck, she told me, “To remind me.”

It was heavy, the sense that she almost certainly wouldn’t remember this very scene, our conversation on the tree house balcony, which she’d insisted on renting for the occasion, despite my telling her that it really wasn’t necessary for her to rent a tree house for our interview. It was on her bucket list, she replied, to stay in a tree house. I didn’t ask if she was dying.

She would sometimes tell me she believed that she and the others had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), as in, the condition that football players and boxers can get. Which made some sense to me, given that it results from repeated head trauma. She’d discuss her symptoms and tell me about her efforts to get cognitive testing from various neurologists.

I’d write about this scene of us by the river, I offered, in my piece. That way, she could read it eventually, and remember it that way.

Yes, she’d remember it that way, she agreed.

The idea pleased her.