An-My Lê is a photographer whose body of work, developed across thirty years, has been focused on the various manifestations of war and conflict—not as fixed moments in history, but as deeply imagined realms through which attempts are made to reapprehend the past or, however fitfully, imagine a possible future. As MoMA curator Roxana Marcoci has noted, Lê’s work highlights “intimacies that grow, paradoxically, out of conflict.” Thus, seemingly disparate geographies and histories are drawn closer together, suggesting relations across time and space: the Mekong Delta and the Mississippi Delta; deserts in California and the Middle East; wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and the United States; rivers and roads demarcating and erasing borders.

Lê’s gaze, like the military personnel and reenactors she works with to make her photographs, is focused on pushing the present moment, scene, or setting toward what is not there; rehearsing and practicing the act of launching oneself into the landscape toward what is held in the mind’s eye. War and conflict—whether anticipated through training maneuvers and simulations (29 Palms); or approached in its aftermath as a reenactment (Small Wars); or limned to reveal its displacements and continuities by shifting the focus from figures to the landscape (Viet Nam); or considered through the lens of past and current acts, sites, and emblems of contestation (Silent General)—are, in Lê’s photographs, fictions that belie deeper truths about human desires and frailties.

An-My and I spoke via Zoom in June 2024, on the morning after the presidential debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. An-My had watched the debate; I had not—though I had glanced at the headlines prior to logging on and had absorbed that it had been a debacle for Biden, who would drop out of the race less than a month later. Though our conversation did not touch directly on the debate, the urgency of the moment—the unspoken question of What next? What now? for the ongoing experiment of democracy—informed our conversation.

Prior to our call, I had sent An-My this message: “I am curious about the poetics of your gaze—the juxtapositions and shifts in scale, the still and restless eye—which, even as it traces the processes and residues of anticipated or recorded rupture, does so not toward any defined end, but deeper into the mysteries of the nature of self, memory, reality, change, and impermanence.”

Our conversation touched on all that and more: Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish”; Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days; Robert Frank’s The Americans; two iconic images from the war in Vietnam; landscape and land art and view cameras; pornography and Pompeii; notions of the monumental and the subtle and what cannot be “wrangled into the rectangle” of a photograph. Threads of peace, violence, and hope in the face of uncertainty were woven in throughout.

—lê thị diễm thúy

I. Focus on the Hooks

THE BELIEVER: Are you in Brooklyn?

AN-MY LÊ: Right now I’m in Carroll Gardens. But we’re moving. Where do you live?

BLVR: I live in Western Mass.

AML: Oh, you do! I think you have a bunch of photographers living up there near you.

BLVR: In these hills?

AML: Yeah.

BLVR: You were talking about what you say to your Introduction to Photography students…

AML: Yeah, we talk about describing what you see, what the signals are. You look at events and you notice things. How do you interpret that? The photography I’m interested in is one that describes moments, facts in the real world. I always tell my students that it’s so important to describe the world in as many details as possible, and to look for entities that have textures, that have possibilities for an open interpretation. And as the students get more sophisticated, they may capitalize on this possibility.

BLVR: Mm-hmm.

AML: The more you describe—the more precise you are, the more judicious you are in choosing what to describe, in choosing your point of view and the moment—the more specific your photograph can be. But at the same time, it is these descriptive, objective properties that also bring about its subjective aspect and allow us to riff beyond what is in the frame.

BLVR: So you’re playing upon the viewer’s subjectivity through what you choose to describe?

AML: Yes, though when you are photographing, you really shouldn’t be thinking about the subjective aspect. You should be in tune with potentials, but you’re there just to pay attention to how things are unfolding, to the surprises that pop up, and you try to grasp all the possibilities that happen in front of you. With more experience, you understand that certain gestures can lock the meaning into something too specific—in a way that allows only one interpretation—while there are certain other gestures that may provide an open interpretation, depending on who is reading the photograph. Photography is not exactly an equivalent, but there’s something that runs parallel to literature. You have words; you want to use your words to express your ideas; in photography, you have a world you want to describe in a vivid, factual way, not just in order to suggest the moment, but to speak about human existence.

BLVR: What did you mean by “signals” earlier? Material signals?

AML: Yes, absolutely material signals! Cues and signals, as constructs. It’s sort of like that Elizabeth Bishop poem about a person going fishing. Is it called “Fishing”?

BLVR: “The Fish.”

AML: “The Fish”! She describes the specificity of the fish: this humongous, vividly colored animal. But then she zeroes in on the hooks. So what? They’re just hooks! But then she realizes that that fish had been caught previously, that it had traversed, already, difficulties and so much else in life. And she decides to let it go.

BLVR: Part of what you’re talking about is the eye that’s brought to bear upon the thing, the consciousness that’s brought to bear upon the thing. That consciousness is reading, gleaning, and perceiving that the fish is a thing in time—that it has a history. And then there’s the response. So in photography, what you’re describing are these split-second, unspoken choices. You’re absorbing all the signals and cues, and there’s a constant re—

AML: Re-shuffling and re-shifting.

BLVR: Right, if you maintain soft eyes, a soft gaze, so as not to fix the frame.

AML: [Laughs] Well, at some point you have to fix.

BLVR: What is that point?

AML: We use different methods, the way one would in fiction, paying attention to the details, the gestures. For example, a man is walking, and sometimes the walk looks generic. But perhaps there’s some kind of gait that is interesting, that suggests: Oh! There’s an effort there, or this is something they do all the time, or they’re just walking really quickly. Those differences matter because they can add up to suggest something about his personal history. Describing space is equally important. How do you draw a viewer in? How do you create tension?

BLVR: Why is tension important?

AML: It keeps everything taut. You often read a photograph from left to right. But sometimes you may be taken for a spin. It is important to be able to draw the viewer in and give him some sort of experiential, physical experience. Landscape is what I am most comfortable speaking about. Olmsted, he designed Central Park, Prospect Park, and has been very influential. I am often telling my students that they need to photographically construct a landscape similarly to the work of a landscape architect. You need to provide an entry point and lead the viewer through your photograph the way the architect may take a stroll over a bridge, through meadows, up a hill. You want someone to get lost in the image, and as they get lost in the image, they start thinking about everything they read and what it means to them.

BLVR: Associations.

AML: Associations, history, personal history. Often, artists who are not photographers think there’s a lack of authorship in photography. Because you just push a button, right? It’s not synthetic, the way painting is, where every [mimes a brushstroke] counts. But there actually is! Where you place the camera, the moment, the height. There are a lot of small things that seem not so obvious, but they do matter. And there’s a consistency too. Everyone can make one or two great pictures. But how do you build up the body of work?

II. “What has not been answered?”

BLVR: I was able to catch your show [Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières] at MoMA, and it was great to see the range of forms. In seeing so much of your work in one space, I really had a sense of the development over time: that movement from the early work, when you first went back to Vietnam, toward something more immersive, and the emergence of different bodies of work.

In terms of the photographs you made in Vietnam, you have talked about how you had certain expectations, and then you arrived, and it was neither what you remembered nor what you’d been told, but everything in between. Your eye initially looks toward people, but then your eye shifts to the landscape—rivers and things—which gives you a sense of continuity. Change and continuity—these seem to be recurring themes in your work: what remains, what is altered. They feel very much like explorations that are not necessarily planned but organically unfolding.

AML: I think that’s very perceptive, that notion of something changing over time. But then somehow you still need to find something that reverberates, something that you can identify and carry with you, something that feels substantial. This is what’s anchoring me. What has not been answered? What are the next questions? What was I not able to do? What would I like to try? That’s what always leads me to the next thing. In the end there are all sorts of intermingled, unified questions that somehow connect back to one another.

BLVR: I know that Michael Heizer’s work and [Robert] Smithson’s work are potent for you. I was thinking about this as your “double negative”: You’re not a victim, and this is not about trauma. Those might be frames that others want to bring to the work or bring to you as an artist. But you’re like: That’s not mine, and that’s not me. As a result, your exploration of war, the psychic aftermath of war, the anticipation of conflict, as well what it means to prepare for an imagined event—it’s all so complex, the threads you’re weaving. And throughout, you shrug off these two notions of the victim and the trauma. Not that there aren’t consequences of these events. But you resist those two frameworks, and that is what allows for the depth and richness and continual movement in your work.

AML: That was not always clear to me. Making the work slowly made me understand. At first, people would suggest ideas for projects and it was always, No! When I first went to Vietnam and I was photographing landscapes, friends would say: Oh, you should look at the effect of Agent Orange! Or: You should go to the battlefields. That is the direct causal effect of war, and of course it was devastating. But it was too specific, and I wanted to move to a different terrain.

How do you move beyond the specificity of your own story? I had a teacher in graduate school who was very matter-of-fact. He said: Nobody cares about you. They just care about what’s on the wall. If you make great work, people are interested in everything. But your story itself is not that interesting. Nobody cares. He was very blunt.

BLVR: But that’s useful!

AML: It steered me on the right track.

BLVR: It’s the work that remains. It’s the work that is the site of exchange and interaction.

AML: The idea of the victim is also complicated. When my family came to the United States, we were showered with support. We felt saved. My father could have been in the reeducation camp for dozens of years because of his involvement in education. And we could have lost years because of the nonexistent education in Vietnam at the time. We felt so lucky. We got support, and we were able to go to good colleges. At the same time, to Americans we were reminders of the devastation—the fact that Vietnam was such a failure. They thought of the violence; they thought of the consequences on American vets. They were reminded of the student protests.

BLVR: Did you feel that—

AML: It was a burden.

BLVR: Uh-huh…

AML: When I was in college, whenever the word Vietnam popped up, I could feel the tension; people avoided looking at me. I remember seeing [the Oliver Stone movie] Born on the Fourth of July with friends, and I would be vocal about something, and they would go: “Oh, somebody’s getting personal here.” I felt like I was carrying the burden of that failure. We were accepted, we were embraced. But at the same time, we were proof of this awful episode in Vietnamese—in American—history. It was my goal to get past that. I am not a victim. That’s why that picture of the young girl burned by the napalm bomb [Nick Ut’s The Terror of War] is traumatic to me. The way people seized on that image—it made sense: they wanted the war to stop, and these were iconic images that were helpful in that sense.

BLVR: The Burning Monk [Malcom Browne’s photograph of Thich Quang Duc’s self-immolation in 1963] is also iconic, but very different.

AML: Especially the pictures that were taken at the beginning, before he was completely immolated. It felt like one of the rare moments when violence and peace came together at the same time. It was an incredible act of protest and resistance.

BLVR: Returning to Heizer’s and Smithson’s work and the notion of monumental and massive engagements with land. Those guys are digging trenches, and the work is about what’s not there: this wedding of destruction and creation, of nature and man. We have these processes that are man-made, like war. War is something that we as a species do. We make it, and peace is something we also make. With Thich Quang Duc, it was all so intentional. Someone is willing, with their own body, to illuminate the possibility of hope. There are others who have gathered there to witness it. We wouldn’t say that’s an individual act. That’s a collective act.

AML: It’s a collective act. He was supported.

BLVR: And it was planned. It reflects back on everything—everything that is at stake about being alive. It is such a spectacular act, but it’s also so deeply subtle where it wants to reach.

AML: It’s small, in a sense, but it’s so far-reaching.

BLVR: In the midst of a monumental thing like the war. These shifts in scale also come up again and again in your work.

AML: Scale is something I’ve definitely been concerned with, whether we’re talking about landscape or even portraiture. At first, it was insurmountable, thinking about it.

BLVR: How come?

AML: To deal with something that’s greater than you, that big subject of war. The big subject of conflict. Can you do that as a photographer, not using a lot of text and using simple titles? When you’re not a writer, when you’re not a researcher, a political scientist, a historian?

BLVR: And you’re not doing reportage.

AML: Right. Trusting that the medium, in the way I’m using it, can carry the day was not always clear to me. But it’s the notion of scale, yes. It’s obvious to me in the landscape that there are so many opposing forces. The idea of destruction but then of renewal. Or the idea of constructing something, only for it to disappear over time. But then there will be another movement to counterbalance that. Often there’s order and disorder in the way things come toward an equilibrium. Perhaps it was very naive of us to look at America and think: This is the land of opportunities. This is where we can rebuild our life and give a future to our children and grandchildren. Now democracy in America is questionable. But that’s an experiment that’s been going on since Walt Whitman first wrote about it. It’s still an experiment. America is a very young country, so I am hopeful that things will continue to forge ahead.

BLVR: You’re hopeful.

AML: I’m not brushing things under the rug. I see what is happening and it’s stressful, and that’s why I started photographing in the United States. But I am hopeful, yes.

III. A Stitching of Old and New

BLVR: It’s interesting that you’re pulling from Walt Whitman’s book Specimen Days as you travel the country for your current series, Silent General. Whitman is attending to Confederate and Union soldiers. He sees into the moment, the wreck, the ruin. And he also maintains hope by doing, by dressing wounds and such.

Equilibrium is a word you keep coming back to. In your conversation with Hilton Als [first published in Aperture in 2005], you also talk about clarity. You’re working to arrive at clarity, which is “not necessarily the truth.” I found that so interesting. When something becomes clear, there’s the follow-up question: And then what? The work is not prescriptive. It doesn’t say, Therefore, do this, or Do that. It’s almost like sounding a bell. And in that possibility of clarity, one comes closer to perceiving all the entanglements, all that is actually present and interlaced, what cannot be cut off from the other. That is what prompted my question about the poetics of your gaze, a gaze that has developed over time, and that is not separate from your intellect and your passions and concerns—it is the inflection of how you might touch the world through the camera’s lens.

You’ve had such a long relationship with the view camera; you talk about how it’s clunky, how you clamber with it. It makes you visible in the landscape. It is a signal that something is happening. What is your relationship to the camera?

AML: I started using it because I was working for this guild of craftsmen [in France] where I photographed objects and architecture. The view camera is ideal because of its ability to control perspective and focus. It uses a much larger negative, which can record a landscape in its minute details. A print from this larger negative describes space in a more experiential way. Enlargements really hold up. You can feel the air between things. But the camera is very cumbersome. It’s heavy.

BLVR: How heavy is it?

AML: It’s not just the camera itself. You have the film holders. Instead of using rolls of film, you have sheets of film that fit into these holders. There’s only two shots per holder, and each holder is probably heavier than a paperback. I carry thirty of those—that’s sixty sheets of film—for a long day of work or half a day, if it’s really busy, and then I reload. Then you have to carry all the film and the changing bag. You have to set up, you have the tripod. Then there’s that disconnect of seeing the image through the ground glass upside down, and then having to close the lens—you stop seeing what it is you’re photographing.

BLVR: When you stop seeing, is it kind of like a held breath? What is the sensation when you stop seeing?

AML: I always pre-visualize my frame. I try to imagine where my frame is out in the landscape, and which people are coming in and out of the frame. It’s not such a self-conscious act anymore. It taught me to see the frame before I open my camera.

BLVR: In your mind’s eye?

AML: Yes. I would drive around, and I would look, and I would already see the picture. The camera is often just for the minor adjustments. But sometimes I don’t see it, even though I know I have to make a picture. Then it’s a bit of a struggle, looking through the ground glass. There’s also the fact that you can’t photograph action. Sometimes you can fudge a little bit. But basically, you have to ask someone to hold still. Or you have to find ways to photograph things either before they happen or after they happen. That taught me a lot, in terms of thinking about the nineteenth-century photographers who covered the Civil War, like Timothy H. O’Sullivan. He set things up and photographed before or after a big battle. Or I have to look for something that is not the main event. That has become my MO—figuring out something even though I am not there in time, as an event unfolds.

BLVR: What about the body of the camera in relation to your own body?

AML: You want to be subtle, but how can you be subtle when the camera itself is so commanding? Everyone pays attention to you, so you have to perform.

BLVR: What are you performing? Are you performing the photographer?

AML: When I first photographed in Vietnam, I was really self-conscious. Do I need to look like I know exactly what I’m doing? Am I asking them to move around too much? Do I look like I don’t know what I’m doing? But there’s something about the camera that gives you authority. I became less self-conscious about how people perceived me. Then there’s the issue of working with an assistant. When I was working in Twentynine Palms [for 29 Palms, a series in which Lê photographed Marine Corps recruits at a training camp in the Mojave Desert], you often have to pack up in two seconds, and you gotta jump in the Humvee. You’re carrying all this stuff by yourself, and as a result you’re exhausted by the end of the day. And then you can’t work as well the next day. So I started asking students to come with me when I couldn’t afford an assistant—which means you’re performing not only for the people you’re photographing but for whoever else is looking at you. I quickly got over that. But yes, there is something performative about knowing that everyone’s looking at you.

BLVR: You’re the cause of the pause!

AML: Yeah. In the same way that I don’t like asking people for help, while I’m photographing, I also don’t like to stop things and say, Oh, can we do that this way. But sometimes I question myself: Did I go far enough? Did I ask for everything I wanted? Did I stick around long enough?

BLVR: Going back to 29 Palms, the second time you were there, after COVID, you were coming to terms with the fact that your mother was in the early stages of dementia, which was exacerbated by the isolation of COVID. You were at Coyote Perch [part of the Marine Corps Air-Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California] and looking out onto a landscape you had seen before. But then things became “unmoored”—that was the word you used. You were experiencing an overload of information and stimuli. And you arrived at this realization that you could no longer, in your words, “wrangle things into the rectangle.” Instead, what was required, you noticed, was a more immersive response. I feel like this is one of those key moments in the trajectory of the body of your work, where what’s happening inside you in relation to the landscape and what you’re looking at comes to a head. Because “the rectangle,” or the frame you’re used to, is no longer sufficient. There emerges a new relationship with both your camera and your work. I am very interested in that moment—because it’s bodily.

AML: Yeah, it’s bodily. I didn’t feel like I needed to produce something. I allowed myself to just be in the moment and experience and get emotional. I let my mind wander.

To go back to land art: I still haven’t seen Double Negative, and I saw Heizer’s City very recently, long after I made 29 Palms, but I had been thinking about visiting various land art as a way to escape photography and be more physical about dealing with the landscape—to be more ambitious, in a way, or break out of the strictures of photography. I was just tired of those strictures, and I wanted to be out of bounds. The larger scale of the prints in 29 Palms and the projections allowed me to do this.

Around the time I got out of grad school, photographers felt the need to make work that would hold up in an art gallery versus a photography gallery. There was always this notion that you should print your pictures as large as possible. I resisted that a bit. But maybe this was a way of not just making a huge print, but making something that is physical and experiential, something that is more of an installation. That’s how the idea of the cyclorama and the circular installation of Fourteen Views came about.

BLVR: Which is interesting because the cyclorama points back to early photography and to early moving images.

AML: It’s still about tradition, yes—I sort of love that. I could have gone completely high-tech and digital. But I was more interested in showing how it could be both immersive and rudimentary at the same time, which is the way vision works. How can you connect a horizon line? How can your eyes associate two structures that are very different things? The eye allows you to connect many different things visually and intuitively.

BLVR: It’s a leap, or a kind of stitching.

AML: Yeah, it’s a rudimentary stitching. I wanted to retain that sense of something being simple, of things being made by hand—something that hearkens back to the nineteenth century. But at the same time, I don’t fetishize old things. I’m totally excited about new technology and I use it a lot. I love this hybridization of the old and the new. This hybridization is also in the content of the work: talking about the present, perhaps suggesting the future, but also walking back through history.

IV. “You have to meet the devil halfway”

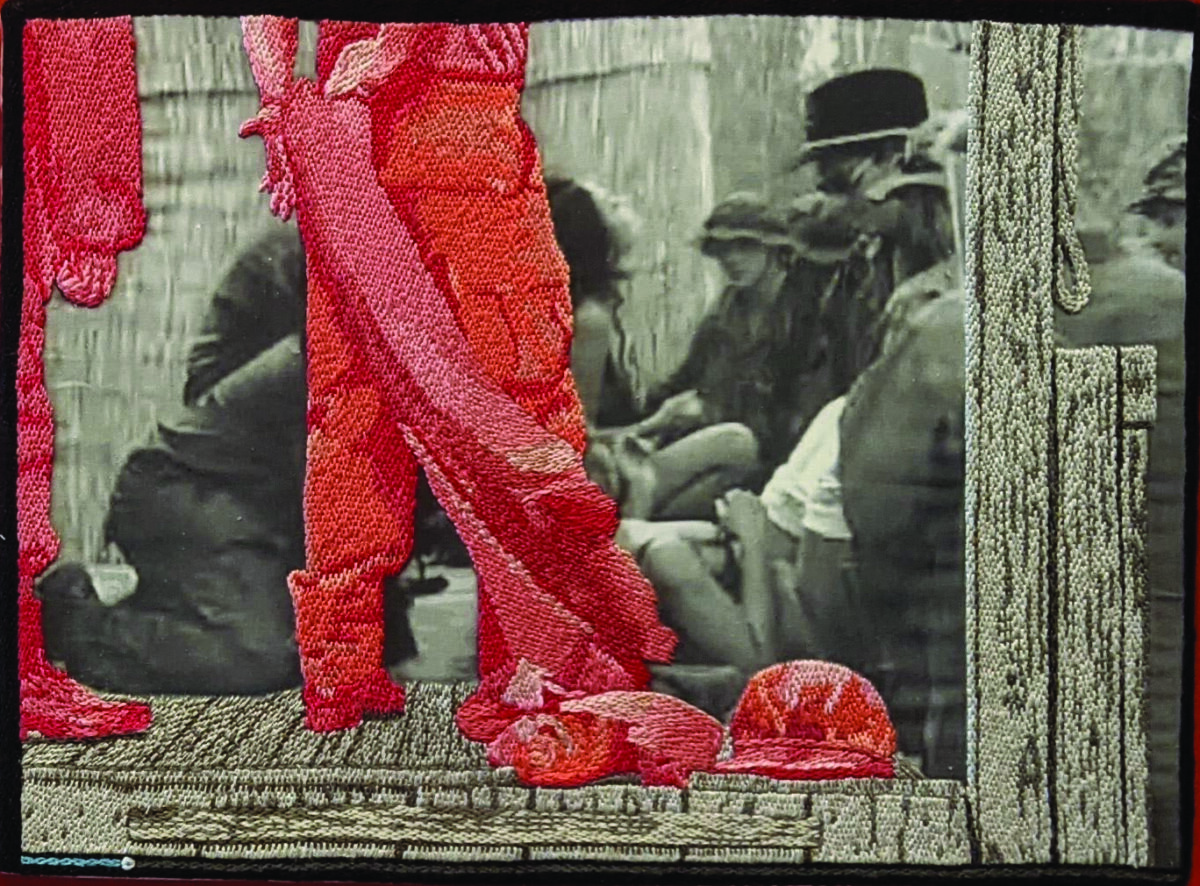

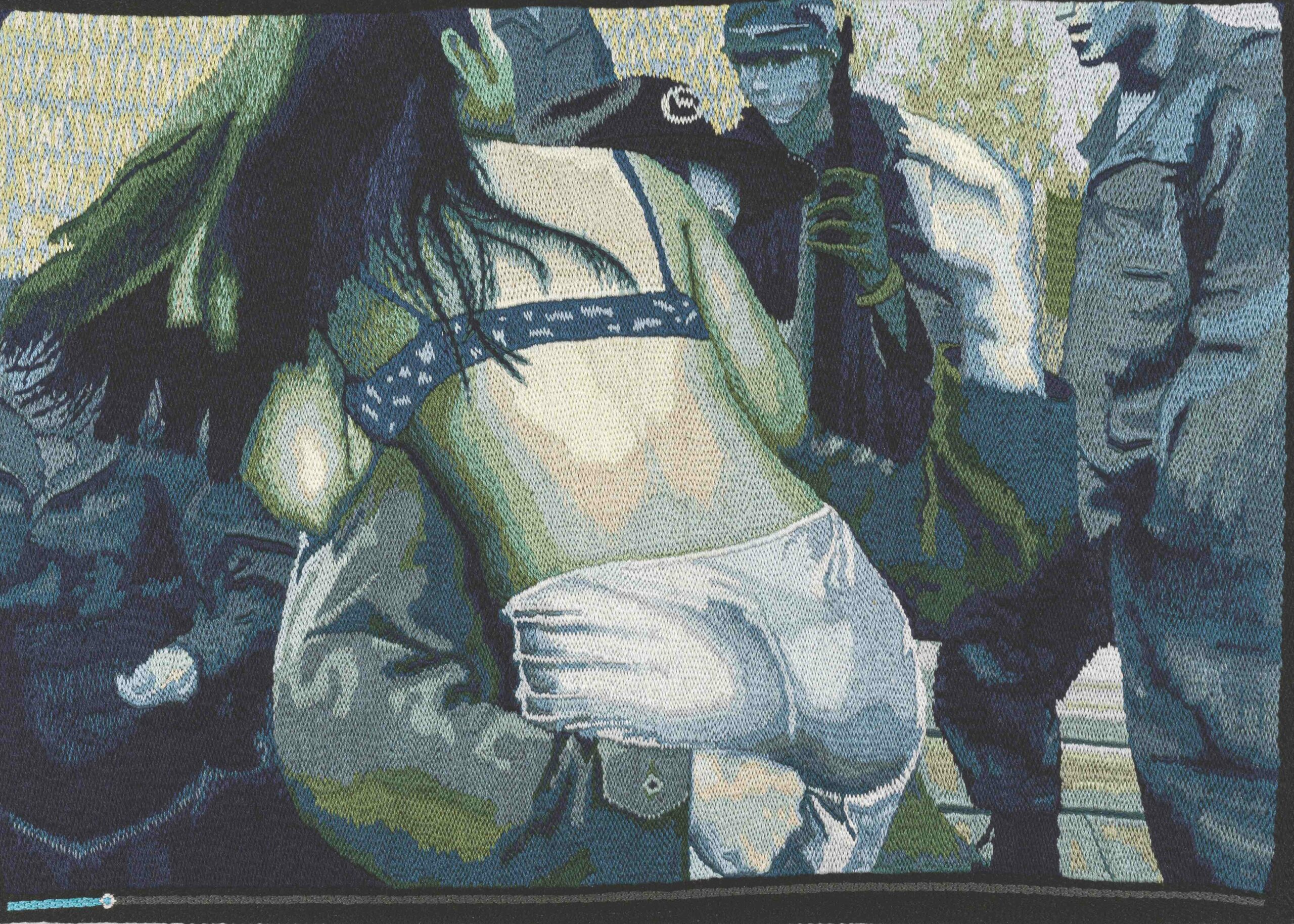

BLVR: Let’s talk about Someone Else’s War (Gang Bang Girl #26) and Gabinetto. There, you’re going from a film, to a video, to making stills, which you’re then turning into embroidery. I was curious about your interest in having these different frames.

AML: Yeah, there’s a kind of layering.

BLVR: A layering. And then going back, the frescoes [in Pompeii]. You’re framing the pornographic.

AML: There are the larger landscapes, the establishing shots, and the more explicit ones. When we embroidered the explicit shots, my assistant and I just kind of scaled the images down to the size of a laptop, which is how people watch porn. And we were able to control the colors more.

I’d had that film [Gang Bang Girl #26] for so long, since 2000. It had everything I was interested in: this idea of a fake war, of people reenacting something, of landscape—because it happens in the landscape, which is really unusual. But at that point, when I first got ahold of the video, it was too intense, so I put it aside. Then at some point I realized it was something I needed to tackle. Even though you don’t want to look at it, pornography is so present in society. The fact that people went to such great lengths to make this film, it must have been popular, right? Just as popular as the fetishization of nurses and doctors. You have to meet the devil halfway. I stopped thinking about the intensity of it and got to work.

BLVR: In a way, you’re overwriting with embroidery thread.

AML: I’m covering it up. I’m trying to make it—what’s the word?—less problematic, or less jarring, similar to how I photograph people rehearsing for war. Even though I had wanted to go to Iraq, I ended up photographing people who train for war. Maybe it’s a way to not be the photojournalist who’s right there as the thing happens. I think every kind of action is a removal of the real thing, turning it into something that’s hopefully more revealing and more interesting.

BLVR: You’re handling one of the aftereffects of the war, the continuation of one of the lines of fantasy. Like earlier, when we were talking about the cyclorama and the idea of pulling something from the past into the present. The embroidery thread pushes the image back, but also surfaces something.

AML: Right, and the image is still present underneath. Most people have watched some kind of porn, so they’re familiar with the types of figures and actions. I think, with our imagination, we can fill in the disconnect very quickly, on top of the stitching. I had a bit of an issue with how beautiful the transformation was—from pornographic film to embroidery.

BLVR: Was the softening an intention?

AML: It’s an intention, yes. Because that’s what the medium of embroidery does—it removes some of the specificity. When you photograph, you want the specificity. But I think that’s what I learned from painting: If you look closely, you can’t really see what you’re looking at. But as you step back, the image comes into play. Instead of brushstrokes, we’re using stitches. And over time I became more sophisticated in terms of color theory. At first, I just used real colors. Like: This is green, so I’ll use green thread.

BLVR: Matching.

AML: Yeah, matching. But then eventually I completely changed the color palette and went with only pinks and reds or blues or some other totally new palette, which was fun and experimental. I stopped seeing the image itself. But I’m glad the final work still contains its origins, in that there are whiffs of this issue of disparate power—the sex labor, the vulnerability of children and women in war. So many themes are still embedded in there. I brought the pictures that I had made in Pompeii [to the installation of Someone Else’s War (Gang Bang Girl #26) and Gabinetto], not just to talk about desire or eroticism, but to talk about this imbalance in power. Many of the sex workers back then were slaves. They were spoils of war. This may seem so jarring and awful, but it’s always been war and sex—they have always been connected somehow.

BLVR: So what happens, say, in Small Wars, when you are the only woman in the woods with these guys who are doing the reenactments? I loved that in your conversation with Monique Truong and Ocean Vuong [at MoMA in March 2024], you said, “They were working out something, and I was working out something. And it was the safest war.” That notion of it being the safest war was so striking to me.

AML: I have to say, those reenactments were safe physically. But emotionally and psychologically, they were not safe at all, because in my head it made me go back and think about both the war and what it means to be an object of desire. I think those guys really believed in the myth of the Vietnamese woman, the female warrior. I’ve had some of them come up to me with crazy comments. It was shocking at first, but then they would say: “Oh, we’re just in character,” or whatever.

BLVR: You were entering into their reenactment, but you were also making the pictures. I was curious about the process of setting up the image, assuming the role, playing the role. How long did the take go for after the image was made? After you set it up, when did the reenactment pick up again without the camera?

AML: I switched between being an actor and being a director.

BLVR: It sounds like you were also conscious of a certain gendered dynamic that still exists, since you were the only Vietnamese person and the only woman there.

AML: When I wore the Vietcong black pajamas uniform, some reenactors would come up to me and say, “Oh, you’re so hot.” There’s a picture that a friend took of me holding an AK-47, which is not in Small Wars. But it’s one photograph in a stack of prints that I had brought back to the reenactors to thank them for posing for me. I never thought it would be so popular. I thought they would prefer the pictures of themselves. Instead, many of them wanted that photograph of me. They even offered to buy it. Something about that photo really triggered their imagination—I’m sure it’s based on movies and literature about Vietnam they’ve read. It happened mostly when I wore the VC uniform. The North Vietnamese army uniform was not as interesting to them.

That whole issue about being an object of attention, or being hypersexualized as an Asian woman, was one of the things, among others, that led me to really push forward with the embroidery. Even though the embroidery happened many, many years later. You see something that’s interesting and you don’t know what to do with it. You put it in a drawer, and then it comes back later.

BLVR: It has a kind of murmuring quality. It asserts its voice at some point.

AML: Yeah, the reenactments also helped me realize that I can make something productive out of this experience and be a director and take charge. That was very empowering—that I could help us understand something; that the work is as much about Americans’ popular imagination of the war in Vietnam as it is about the event itself.

V. The Arc of History

BLVR: How do you feel as we move further away from the time of the war and its direct aftermath?

AML: When I made that work, it was before we had invaded Iraq. I think Vietnam was still the main war that people remembered. Afterward, things shifted, but I shifted as well. As our politics became more embattled in the United States, I shifted to photographing here. I wasn’t sure if I could be inspired by a subject that was nonmilitary, non-war-related. But I realized that my work is about conflict, and we are deep in a contemporary conflict in the United States.

BLVR: When was the shift?

AML: I finished Events Ashore [a series in which Lê traveled with the US Navy on maritime and coastal missions across nine years] in 2012 or 2013. Then I was at a bit of a loss as to what to do next. I was invited onto the set of [the 2016 historical war film] Free State of Jones by the director [Gary Ross], and I started photographing their setups of the trench wars, like the Battle of Corinth. I loved working on film sets—the preparation, the repetition reminded me of working with the military. I thought those pictures alone would not be enough for a project.

BLVR: But that’s what generated the first fragment for the project Silent General. So you’re stitching together these fragments…

AML: Yeah, and then other works in the South, in the beginning of the lead-up to the presidential election of 2016. When things started really unraveling in the United States, it made me consider the American road trip for the first time. As much as I love Robert Frank—I’ve been teaching him for a long time—I never felt implicated in it. I realized that I needed to do my own American road trip. And that’s what I’ve been doing.

BLVR: The novel I’ve been working on is deeply informed by Robert Frank’s The Americans. The notion of what “the road” is, the road as a ribbon. And this being such a big country! When you move through it, the air changes, the landscape changes, the people change, the accents are different. It’s when you move through it that that you feel the density of the atmosphere, and the history. I recognize that in your work. I spent some time in Marfa, as well. Pinto Canyon and the border patrol station. It’s so close to the Rio Grande. Mexico is right there. In parts of the Rio Grande you can just walk across the border.

AML: There’s such a fluidity there. So the idea of a wall, per se, is not necessarily a solution.

BLVR: I have a friend who lives out there. She’s married to someone whose family has had a ranch there for some time. And migrants come through the land. They have bits of carpet that they pull behind them as they walk, to hide their tracks, to avoid border control. These are the layers of what is going on on the ground.

AML: And people come to work for the day, and then go back across the border. Or people cross to have lunch with family. It’s so organic.

BLVR: And medical care. It’s very porous. It relates to that question of what makes America America? As you’re on your road trip, what is it that you’re gleaning? What is your camera picking up?

AML: This democratic experience, we struggle to realize, is complex because of how vast and wide and wild the landscape is. I don’t think we’d be who we are if we were the size of France. Size-wise, France is smaller than Texas.

Toward the end of Walt Whitman’s life, after he had a stroke, he started meditating more on the landscape—what it means, and how vast and wild it is, but also how restorative it can be. It’s always that push and pull. We are always focused on the current moment, but still we need to step back and look at the entire arc of history. Perhaps this moment is just a very tiny fraction of our history, and things will come around.

BLVR: Thinking about landscape, it’s hard to keep your eye on the simultaneity of loss and emergence.

AML: Well, with Spiral Jetty, what peeks out versus what remains submerged is all dependent on the time of year.

BLVR: Time plays such a big part in what becomes visible. One thing we didn’t really get into is your work in color. In Events Ashore, color allows you to differentiate between the sky and the sea. You were working in black and white for so long.

AML: In black and white, you pay more attention to the way things are drawn. You are removing information by removing the colors. With less information, something else happens. Maybe your imagination is forced to play a little bit more. The color in Silent General connects it to the unfolding of today, the contemporary world. There’s an urgency there.

BLVR: You’re clearly very sensitive to the texture of color, of light. You’ve talked a lot in interviews about being a “straight photographer,” but part of what’s so poetic about your work is that sensitivity.

AML: I think the details provide the physical experience to the viewer. I like to try to pack as much as possible into a photograph. Whitman was a journalist, and you can sense that descriptive quality in his work, which is poetic but still very concrete. I love that. And that’s what’s great about photography—how concrete and specific it can be. But also poetic.

We haven’t yet talked about truth. [Wags her finger]

BLVR: We didn’t talk about truth!

AML: Maybe it’s for another conversation.

BLVR: I love that you wagged your finger… so Vietnamese! You were like, We didn’t talk about truth.

AML: Because that is the scandalous part of photography. People equate photography with truth. But all photography is fiction.

BLVR: Maybe photography reminds us about the construction of truth.

AML: Or the construction of a certain moment that you want to draw people into. I’m surely not interested in telling people what to think.

BLVR: You’re not prescriptive. I totally get that! There’s a steadfastness, but it’s not a conclusion.

AML: I mean, I know what I think.

BLVR: You just don’t tell me!

AML: I hate when I read or see a movie and I feel like they really tried to manipulate me. And maybe I am manipulating you a little bit by providing all these facts.

BLVR: But you’re creating a world.

AML: Yeah, the way a fiction writer does.

BLVR: Yes, there’s a kind of architecture.

AML: I want my world to be convincing. I want you to feel that you are experiencing something.