Ten years ago in Nevada City, California, I encountered two coffee mugs in the front seat of an old Mercedes station wagon belonging to Joe Meade, an artist and collector. They immediately caught my eye: oversize and made of white porcelain, they were wrapped in charming illustrations, quirky line drawings depicting a mass of rabbits tumbling in playful, erotic entanglements. “Those are cool,” I said. “What are they?” “Woah, dude, you haven’t heard of Taylor and Ng?” Joe was delighted. “You’re gonna love this. It’s very Bay Area.”

I held the cartoon-animal-orgy mugs in my lap as we drove to Grass Valley, and Joe, with his encyclopedic knowledge of California ceramics, gave me a crash course on their cultural significance and the life of their maker, the late artist Win Ng. Created for the home-goods company that Win cofounded in 1960, the mugs were subtly provocative mementos of mid-century San Francisco, evoking the sexual revolution and the gay civil rights movement. Though they joyfully depicted free love, they were sold in high-end department stores and made their way into the homes of everyday people—not just those inclined toward countercultural and queer lifestyles. In addition to running his company, Joe said, Win Ng was an exceptionally talented abstract sculptor working at a pivotal moment in California ceramics, a time when the medium was expanding beyond its siloed place as craft and into the world of fine art.

At the time of my ride-along with Joe, I was feeling like an outlier in my master’s of fine arts graduate program in San Francisco. While my peers were casually discussing theory at the bar, striving for commercial gallery representation, and immersing themselves in the Art World (capital A, capital W), I was emphatically not. Instead, I was a graphic designer and journalism school dropout, interested in the vernacular and in hyperlocal narratives of place, especially within San Francisco, where I was born and raised. Win’s story—of someone who straddled the dualities of art and design, of commerce and concept—felt like a gift, like a taste of something I was hungry for. Despite the art history classes I’d taken, and despite my attraction to homegrown Bay Area art scenes, here was a San Francisco artist I’d never heard of.

As the years went by, I continued to encounter Win’s work in improbable yet familiar places. I found him on my mom’s bookshelf, in a 1971 book called Herbcraft, published by Yerba Buena Press, an imprint of his company. Inside, on the textured, cream-colored pages, were folksy, near-psychedelic drawings of nude waifs sitting on toadstools beside enormous sprigs of mint. I found Win in my grandmother’s dank cabin in the redwoods, when I noticed, after decades of visiting, that the doorstop holding open the bunkroom door was a Taylor & Ng bacon press, a grinning cartoon pig cast in iron. There he was, peeking out of my aunt’s bin of cleaning rags: a Taylor & Ng Christmas dish towel from 1983, soft and stained, featuring an ice-skating rat wearing a Santa hat. My chance meetings with these objects in my everyday life stoked the deepest sense of intrigue. To me, they represented an undercurrent of Bay Area material culture, mementos of another time, place, and energy. I was determined to learn more, so I began my process of inquiry in a place I know well: the internet.

Win Ng was born and raised in Chinatown, one of eight children. Starting in the mid-1950s, he contributed to an important movement in ceramics, as part of a loose group of West Coast artists that included Peter Voulkos and Robert Arneson, whose nonfunctional, abstract work helped shift the medium from a utilitarian, traditional craft toward a sculptural fine art rooted in expression. In 1960, just as his fine-art career was taking off—with solo shows and critical reviews—Win and his then boyfriend, artist Spaulding Taylor, began to make and sell their functional work together. Their collaboration eventually became Taylor & Ng, an early lifestyle brand that achieved mainstream commercial success. His multidisciplinary practice spanned ceramics, illustration, painting, industrial design, and creative merchandising. A critic referred to him in 1960 as “a veritable dynamo of creative energy.” In 1963, Win told Ceramics Monthly, “I don’t think of art—I just do it. It’s part of living.”

I dug into online newspaper archives, saving every scrap I could find to my desktop. And still, with each new fact I found, a thousand more questions unfurled before me. And what else? I wondered. Who was Win Ng? What could his life tell me about San Francisco? About my own creative practice? I quickly ran into the edges of the internet’s information on Win. His Wikipedia page is anemic, and the few online artist profiles recycle the same information. He is largely absent from the art-historical record, despite his achievements and popularity. I had found a San Francisco artist’s story that I couldn’t easily read elsewhere, a shiny, magnetic bit of intrigue—a story that I’d have to assemble for myself.

When Win’s work found me, over and over again, it spoke to me loud and clear, its personality bursting with humor and warmth. I sensed that his work and story deserved to be known. And so I called strangers, scrolled eBay, and circled the Bay Area to find the objects he made, the places he lived and worked, and the people he knew and loved. I wanted to piece together Win’s story, so that others might know him too.

The first thing Ally Ng says to me when I speak to her on the phone is “My uncle has been kind of a mystery for me, too, my whole life.” She invites me to come over and see Win’s house, one of two mid-century modern homes built from old-growth redwood, in a family compound perched on the north side of Bernal Hill, facing the city. She grew up next door. Her father, Norman, was Win’s brother.

I arrive on a Saturday and can’t find my way in. All I see from the street is overgrown grass behind a low wrought-iron fence. Much mystery indeed. Ally pops out of a hidden door in the fortress of dark-stained wood siding. She’s wearing a sweatshirt that says BERNAL HEIGHTS.

We walk from street level up to an enclosed hilly yard. On the south edge of the large lot is the redwood house that Win had built in the mid-1960s. The yard is overgrown in a way that is common in San Francisco: unruly, lush. Orange-tipped jade plants engulf an inoperative redwood hot tub. Yellow sour grass flowers lean over paths whose cobblestones, Ally tells me, came from the ballast of a ship. At the center is a pond, brimming with life, and from it emerge two Stonehenge-y cobblestone sculptures that Win made.

“He wasn’t, like, a fun uncle who was deeply engaged,” she says. She lists her memories: “He would go outside wearing a silk kimono to water his yard. He smoked Sherman cigarettes, he had a boyfriend, and he had parties.” These parties often involved a yard full of nude men soaking in the hot tub and using the sauna. Ally says she grew up thinking this was typical. “You’re like, OK, grown-up parties are hot tubs and naked people.”

In 1959, the same year he finished his undergraduate studies, Win bought a modest, single-story Victorian house on this three-parcel lot for nine thousand dollars with a loan from the GI Bill. At the time, Bernal Heights was a working-class neighborhood, home to many families who had worked at the naval shipyard in Hunters Point. It had not yet been declared Redfin’s “Hottest Neighborhood of 2014.” There was no microbrewery, no e-bike shop, no pretentious food store selling Maldon Salt and Gruyère. In 1960, the Examiner referred to Bernal Heights as “an area that is attracting artists with its low rents and magnificent views.”

Win’s house is currently empty between renters, so Ally takes me through the sliding glass door into the kitchen. Though the simple, underwhelming galley kitchen doesn’t match the vibey, gourmet, mid-century vision I had conjured in my mind, the rest of the house oozes with character. The living room is clad in rough-sawn redwood siding, with thirty-foot ceilings and parquet floors. Sunlight beams in through the skylights. A catwalk with a black iron railing overlooks the huge living space. All the exterior doors are sliding glass, and all the interior doors have square cast-iron pulls—there is not a single doorknob in the entire place. It feels like a Sea Ranch house, if an artist were peering over the shoulder of the architect, whispering ideas. Ally says that’s pretty much what happened.

Off the carpeted upstairs hallway, each of the bedrooms has a view of the downtown skyline. Ally calls the tiny bedrooms “crash pads,” where she imagines Win’s friends would stay after his wild parties. Michael Hunter, an artist and queer-studies scholar who rented the house for fifteen years, told me two of the small upstairs bedrooms were labeled office and gym in the fuse box. “It was a queer house,” he said, made for entertaining and socializing. “It wasn’t a family house.”

According to Natalie Ng, Norman’s first wife, though, it actually was a family house, at least initially. As soon as it was finished, Win’s parents and some of his younger siblings moved in, and they all lived there together for a time. Natalie spoke of festive weekends, everyone gathering for home-cooked meals and games of mah-jongg.

I turn from the view of the city, and across the hallway I see a mural in the bathroom. Next to a normal old sink and toilet, big tonal stripes and quilted blocks of greens and blues follow the edges of the redwood boards. There’s a hippo bathing and a turtle swimming in the reeds. There’s an artichoke flowering above the water, a green sun, and little plants with perfect circles forming blooms along a curving stem. The mural charms me; I can feel Win’s humor and intention.

I had eagerly accepted Ally’s invitation to visit Win’s house, hoping the place would radiate his energy in some palpable way, so I might glean inarticulable insights into his personality. The vibrancy of the mural gives me a hint of this feeling, but it also illuminates the lack I feel in the rest of the empty house. Without the trappings of his daily life—dishes in the sink, shoes by the door—I can’t get the sense of Win that I had hoped to find.

I’m still thinking about the mural when Ally invites me into her mom’s house next door to see a massive oil painting in the living room. It is one of Win’s later works, an unfinished piece from the last decade of his life. A full golden-yellow moon sits high in a dark blue sky, with rings of light radiating from it in orange, blue, and purple. The textured landscape is layers of green jungle plants. This painting is unfinished because Win didn’t paint landscapes; there are awkward empty spaces within the bushes, reeds, and sky, waiting for animals. The painting gives me the same feeling his vacant house did: that its story is waiting for me to fill in the blanks.

Win moved to Bernal Heights in his early twenties and lived there for the rest of his life. Aside from an army stint in France, the only other place he called home was Chinatown.

His childhood home on Washington Street looked out over Portsmouth Square, a place that has been called Chinatown’s living room. His parents, immigrants from Guangdong Province, raised a family of ten in two two-room flats, where they warmed bathwater on the stove and used a shared bathroom down the hall.

Starting when he was fourteen, Win worked for two years sweeping up in the studio of celebrated Chinese American ceramics and enamel artist Jade Snow Wong. Though she denied being a mentor to Win, his exposure to the craft and the materials in her workspace stuck with him. As a teenager, Win began working with enamel, crafting cuff links and selling them to Italian businessmen in North Beach. By age sixteen, he had rented a storefront on Hyde Street for his budding business.

In 1954, at age eighteen, Win was drafted into the army and spent two years in France. Because of his night blindness as well as his inability to drive, he spent those years working as a draftsman and designing posters. He did not waver in his dedication to his art practice, even while serving in the army; Spaulding said Win made custom drawings on the helmets of his peers. He managed to have two solo exhibitions of his graphic work while in France.

His youngest sister, Mimi, recalled Win returning home from service to the family’s apartment—by then they lived on Green Street, at the border of Chinatown and North Beach. She was eight or nine years old. “My very first memory of Win is a Saturday morning. I was sitting up watching cartoons and the doorbell rang. The door had a glass window and a curtain. I looked through the curtain and saw Win. The others were still in bed. I saw his face! I ran through the house saying, ‘Win is home! Win is home!’” For a while, he slept in the living room on a pullout couch, and later transformed a rat-infested room in the basement into his studio. He had three small kilns down there, Mimi recalled, and he employed Norman and their mother as a production assembly line, turning out small works in enamel.

I think of Win’s family walking these streets, as I walk four blocks from Portsmouth Square to the historic redbrick YWCA designed by architect Julia Morgan. Today, the Chinese Historical Society of America occupies the building and hosts an extensive archive and a gallery for cultural and art exhibits. In 2004, curator Allen Hicks—Mimi’s husband—organized a retrospective of Win’s work, focusing on his fine-arts ceramic sculptures. Allen published a comprehensive catalog with a detailed biography. He sends me a copy in the mail, and I read it in one sitting. For a moment I doubt whether I should even write this profile—it’s all here, thoughtfully assembled in The Art of Win Ng: A Retrospective—but I press on, convinced that Win’s life and work are due for another look. Despite Taylor & Ng’s success and ubiquity, and despite Win’s role at a pivotal moment in the American history of ceramics, few of my peers—even those who are artists and designers—have heard of Win Ng.

Though their business wasn’t officially incorporated until 1964, the seeds of Win Ng and Spaulding Taylor’s creative partnership had emerged in 1959, when the two met through friends at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), which was later renamed the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI).

The Bay Area in the 1950s and ’60s was a potent place for the arts. Energetically, the postwar period brought a sea change of attitudes and ideas. Practically, there was an influx of men returning from military service, ready to attend school on the GI Bill. CSFA’s faculty of this period—among them Richard Diebenkorn, Ansel Adams, and Dorothea Lange—included visiting instructors who brought influences from Japan, Germany, and creative centers of experimentation like Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

When Win returned from the army in 1956, he enrolled in classes at City College, San Francisco State, and eventually CSFA, which he attended for two semesters before graduating with a bachelor of fine arts degree in spring 1959. Spaulding enrolled at CSFA later that year, after his own army stint ended. Win had already begun his graduate studies at Mills College, but they connected in part because both lived in Bernal Heights.

At this moment in the California ceramics scene, artists like Peter Voulkos were making sculptures on a monumental scale: pinching, pushing, squishing, etching, and stacking clay. The Funk art movement was percolating at UC Davis, with Robert Arneson’s humorous, figurative work reimagining ceramics as fine art. According to Joe Meade, ceramics “had always been craft, until this moment and these makers.” As postwar consumers turned toward factory-produced goods, these artists were freed from the constraints of creating functional objects, and eschewed utility to experiment with abstract forms, new building techniques, and surface treatments. Ceramics, once seen as a lesser medium, was now front and center in fine art. “During this period grew the first radical movement to totally revolutionize the whole approach to ceramics,” wrote Artforum cofounder John Coplans in 1966.

At this important juncture, Win was working right in the middle of the swirl. “He was among the first American artists to approach clay in a nonfunctional sculptural manner,” writes Lee Nordness in his 1970 book Objects: USA. In a 1955 oral history for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Win’s CSFA classmate Carlos Villa said, “He was like the star potter of the ceramic [studio]… the pot shop, we called it.… He could do virtually anything with clay.… He did these large slabs and gorgeous—utterly gorgeous—sculpture.” In 1963, Win told Ceramics Monthly, “I don’t care what’s behind me or to the side of me or in front of me. I have a goal in mind and I’m working for that.”

As I read art history books and watch YouTube seminars about twentieth-century Bay Area art, I note only a few minor mentions of Win, despite his accolades, awards, and significant exhibitions. Was he left out because he was Chinese American? Because he was gay? Because he detoured away from the gallery and into business for himself? Perhaps it was because of the perplexing contradiction that he was said to have influenced a critical pivot in ceramics from utility to expression, yet quickly returned to functional ceramics when he started Taylor & Ng.

I crave personal, colorful details about the scene Win inhabited at CSFA, a center of San Francisco art, at a dynamic moment in the institution’s history. Who were his teachers? His classmates? Who influenced his work, and whom did he influence? Hoping for these answers, I take myself to the basement of a brick building on Hawthorne Street, just across from SFMOMA, where the school’s archives are now housed.

The SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archive’s folder on Win Ng is thin, and contains just a few exhibition flyers. Archivist Becky Alexander has pulled records from 1958 and 1959—yellowing booklets and binders with handwritten attendance records and grades inked onto the columned pages. I browse them, seeing Win’s grades in courses like Ceramics Studio, Drawing, and Western Culture (A, A, C−, respectively). In 2004, artist William T. Wiley told Allen Hicks that Win was an understated jokester: “We would sit in… design class, and [the teacher] would be calling roll. ‘Win Ng!’ she would ring out. And each day Win would respond, muttering under his breath, Who the hell is Win Ng?” Allen wrote in the catalog, “It wasn’t an identity crisis, but a jest on labels, a way to keep in check all the egos of his yet-to-become-famous classmates, himself included. It would crack Wiley up each time.”

I am thrilled by the granular detail I encounter in the record books. I see that Wayne Thiebaud and Arthur Okamura taught summer courses right before Win enrolled. In the summer of 1959, just after Win graduated, Wally Hedrick—the esteemed multimedia artist, referred to as “the godfather of Funk” (art), and a founding member of Six Gallery, where Allen Ginsberg’s seminal “Howl” reading took place—taught a precollege summer painting class on Saturday mornings. In attendance? A young, delinquent Jerry Garcia, who ultimately took an incomplete in the course.

I vibrate with each new connection to a storied Bay Area artist. I imagine Win meeting them at parties, passing them in hallways, sharing kiln space with them. I browse a decade of The Tower, a mimeographed student publication bursting with voices and humor and headlines rendered in sloppy bubble letters. I feel nostalgic for something I’ve never experienced.

I leave the building disoriented, with Friday-evening traffic in a raging crawl all around me. Mentally, I’m still in 1959. As I cross the street toward the towering rear facade of SFMOMA and try to remember where I parked, I realize suddenly that I am at the corner of Hawthorne and Howard Streets, and that the SFAI Archive is located next door to 651 Howard, the site of the first Taylor & Ng retail shop, which opened in 1967.

Though Taylor & Ng’s first shop was certainly a landmark for the business, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly where the true company headquarters were, because they had studios, warehouses, and retail stores all around San Francisco—and later throughout the Bay Area, from Brisbane to Berkeley to Fairfield.

Spaulding and Win were studio-mates first, working together in Win’s basement and backyard in Bernal Heights. Spaulding lived a few blocks away. After working alongside each other for a while, they became boyfriends.

In the summer of 1960, Spaulding was in Quebec when he learned that a serious fire had destroyed their ceramics shed. Win had fired their new backyard kiln before a proper hood and ventilation system were installed, and the resulting fire burned his feet badly; he used a wheelchair for weeks. The accident pushed them to rent a studio on Folsom Street beside the Central Freeway, at the border of the Mission District and SoMa. With rent to pay, they expanded their production of salable ceramics—plates, bowls, goblets, slab-built candle towers that looked like buildings—to fund their fine-arts practices. And thus a business was born. From the beginning, the sign above their door read TAYLOR & NG. Though they later incorporated as Environmental Ceramics, and sometimes used this mark on their early products, they always did business as Taylor & Ng.

At the new studio, they had the space to welcome people for visits and sales. They were known for their hospitality, counter to the popular conception of the lone artist, locked in his studio, waiting for inspiration to strike. “Pottery must be born in the city,” Win said in a 1966 Examiner article. “We get ideas from people… We gauge the pulse.” Their sales boasted a party atmosphere. At one, they roasted 120 whole chickens inside their kiln at seven hundred degrees, nestled into Taylor & Ng casserole dishes, which people purchased and took home, dinner and all.

In another often-told story, they invited people to a Christmas party by delivering to each guest a pigeon in a cage. The recipient was to remove from the bird’s leg either an “accepts” or a “regrets” tag, and release the pigeon to return their RSVP. “They weren’t really carrier pigeons, but people thought they were,” Spaulding said. Most just flew away after being released, but when notable columnist Herb Caen tried to return the pigeon he received, it just flew back into his home. It was a prank devised with the help of Win’s brother Ed, a falconer who kept birds in the yard at the Bernal Hill family compound. The mischievous publicity stunt worked: they made it into Caen’s weekly column, a uniquely San Francisco achievement. Caen wrote, “This is to inform Taylor & Ng that I won’t be there and please pick up your bird.” Spaulding told me with a grin that they served squab at the event.

Their successful studio sales encouraged them to ramp up production and expand their product line. Win’s younger brother Herman was brought on to run the studio; he weighed balls of clay and fired the kiln. During this time, Spaulding and Win attended art fairs with their signature spirited booth setups; at gift shows, they refused the folding tables and white satin table skirts provided by the venue in favor of wood and chicken wire, metal grid systems for shelving and display, and sheets of galvanized steel, assembled by Herman. Norman and Natalie began helping with trade shows, and later became partners in the business.

Taylor & Ng popped up in retail spaces, such as a show in 1966 at Dohrmann’s, a boutique glassware shop in Union Square that was later absorbed by Macy’s. The advertisement promised “bottles, jugs, pitchers, vases, bowls, weed pots, frogs, owls, rocks, rills, and other whimsies.” The verbose ad copy continues: “We asked Spaulding Taylor and Win Ng, two of San Francisco’s brilliant artist ceramists… what was meant by their phrase ‘Environmental Ceramics.’ They answered: ‘Briefly, it is another term for functional… ceramics to be used in enjoying everyday living… cooking, serving, entertaining, garden and sky-watching, animating the scene around the house.’”

During this early, experimental era, the company’s first successful piece of environmental ceramics emerged: a chicken cooker. Spaulding designed it and Win refined the first version in 1962; it was a casserole dish hand-built from rough stoneware, with a rounded bottom and a textured, chicken-shaped lid, with the beak and tail glazed a shiny brown. As Spaulding remembered it, a friend who was a buyer at the burgeoning San Francisco discount import retailer Cost Plus asked if they could make a ceramic cooker. Natalie said that stories from her childhood in China inspired the quirky avian twist: she had shared with Win and Spaulding that the poorest people—those with no dishware or kitchen—would cover a chicken in wet mud and then build a fire on top to cook it. In 1979, Win told the Examiner, “The idea of a bullet-shaped ceramic cooker bored us. We began to put heads and tails and feathers in our designs.”

In the beginning, they drove the unfired chickens north to St. Helena in Napa County, where their friend Richard Steltzner had a bigger kiln than they did. By 1966, they were factory-producing a third generation of slip-cast chicken cookers in Japan, made of the highest-quality porcelain. Other cookers quickly followed: a quail, and later a fish.

This leap to outsourcing production was a critical moment in their growth, and the story of the chicken cooker became a loose formula for Spaulding and Win’s future successes: They would accept a suggestion from someone in the know, put their own peculiar twist on it, and then ride the energy of positive reception, iterating toward a final version for mass production. Starting with the chicken cooker, they became masters of the unexpected, offering their customers both surprise and delight.

Taylor & Ng’s first retail shop opened on Howard Street in 1967, kick-starting nearly two decades of steady business growth and expansion of their offerings. The Halloween-week opening party featured an array of goods from local craftspeople and a sidewalk calliope played by Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan. The brick building—originally an industrial dye shop—had an office upstairs, a warehouse below, and a large street-level space, where Win and Spaulding expanded their artistic vision into curation and retail. They imported handmade objects and sold goods made by local craftspeople. “Taylor & Ng selects fine design… for the aware individual,” a 1969 advertisement read. “An eclectic collection of unusual objects is presented for your daily use and continuing pleasure.” Alongside peacock feathers and baskets from Poland, the ad featured a four-foot-tall redwood lion carving by Robert Kingsbury, who later became the first art director of Rolling Stone. The saucy copy concluded, “Come in and satisfy your other self.”

Their creative and entrepreneurial approaches were similarly frenetic. There was no strategy, just experimentation and iteration. Things moved so fast in what Natalie called the “young, adventurous years” that the company had to take things as they came. Mimi told of big, boisterous brainstorming dinners with the retail staff and the art department. “We all really bonded,” she said. “It was just a very carefree time.” She noted that art director Allen Wood could barely take notes fast enough to catch all the ideas flying around.

In 1971, with the publication of Herbcraft by Violet Schafer, Taylor & Ng launched its publishing imprint, Yerba Buena Press, which would go on to release fifteen titles over the next eleven years. The books—including Eggcraft, Breadcraft, and Ricecraft—were catchall, scrapbook-style gift books, boasting recipes, history, folklore, and photographs. Many featured Win’s illustrations. The authors—chefs like Rhoda Yee and Margaret Gin, and food historians like Violet and Charles Schafer—were Win and Spaulding’s friends, whom they invited to realize passion projects that would also support the company’s product line. The series was intended to make Taylor & Ng’s gourmet kitchenware more approachable and ultimately more appealing, as part of a creative lifestyle punctuated by functional, beautiful things.

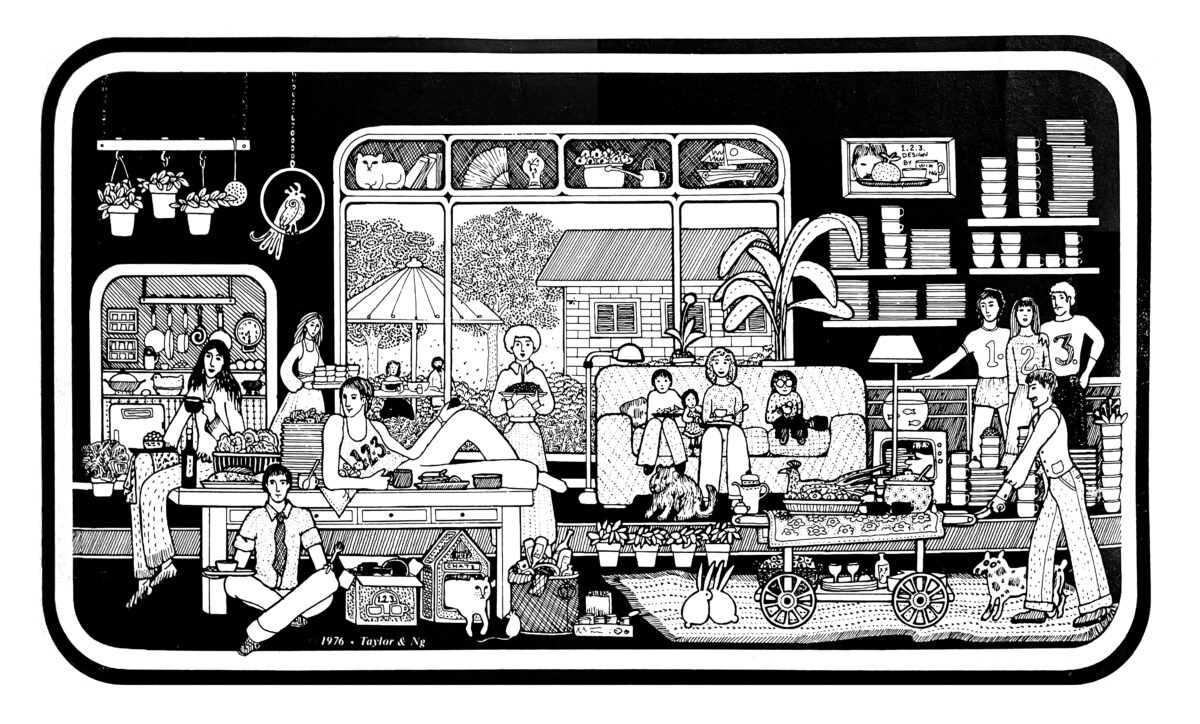

Plantcraft, published in 1973, celebrated the joy of caring for houseplants. It came with a 33 rpm vinyl record with music by composer Ken Ziegenfuss, a friend of the book’s author, Janet Cox, who was the food editor at The San Francisco Chronicle. Win’s illustrations depicted brick apartment buildings with a domestic jungle spilling out the windows, a nude guy doing yoga with a terra-cotta pot in one hand, and, to illustrate the “Propagation” section, a group of frolicking rabbits that was later adapted into a popular line of coffee mugs.

The Wild Wild Kingdom series of coffee mugs—eventually renamed Animates, and generally referred to as “the animal orgy mugs”—emerged around 1979. These mugs are arguably the company’s most recognizable objects and are many people’s first encounter with Taylor & Ng’s work (as they were for me). At first glance, the animals appear to be wrestling, hugging, and dancing. The reality of the orgy might take a few cups of coffee to recognize, which is the genius of its subtle subversion.

Taylor & Ng released twenty distinct series of mugs. Another line, simply called Tall Mugs, featured unique bulbous shapes and monochromatic, folksy drawings of nude men with horses, nude women with birds, and cats with fishing poles. Win’s illustrations were provocative and, over time, brought marginalized perspectives—queer, Chinese American, sexually revolutionized—into the mainstream via people’s bookshelves and kitchen tables. Joe Meade told me the large size and offbeat personality of the Taylor & Ng mugs were perfectly timed to the rise in popularity of herbal tea in the 1970s. “They were savvy, not just in terms of design, but in knowing what people wanted,” Joe said.

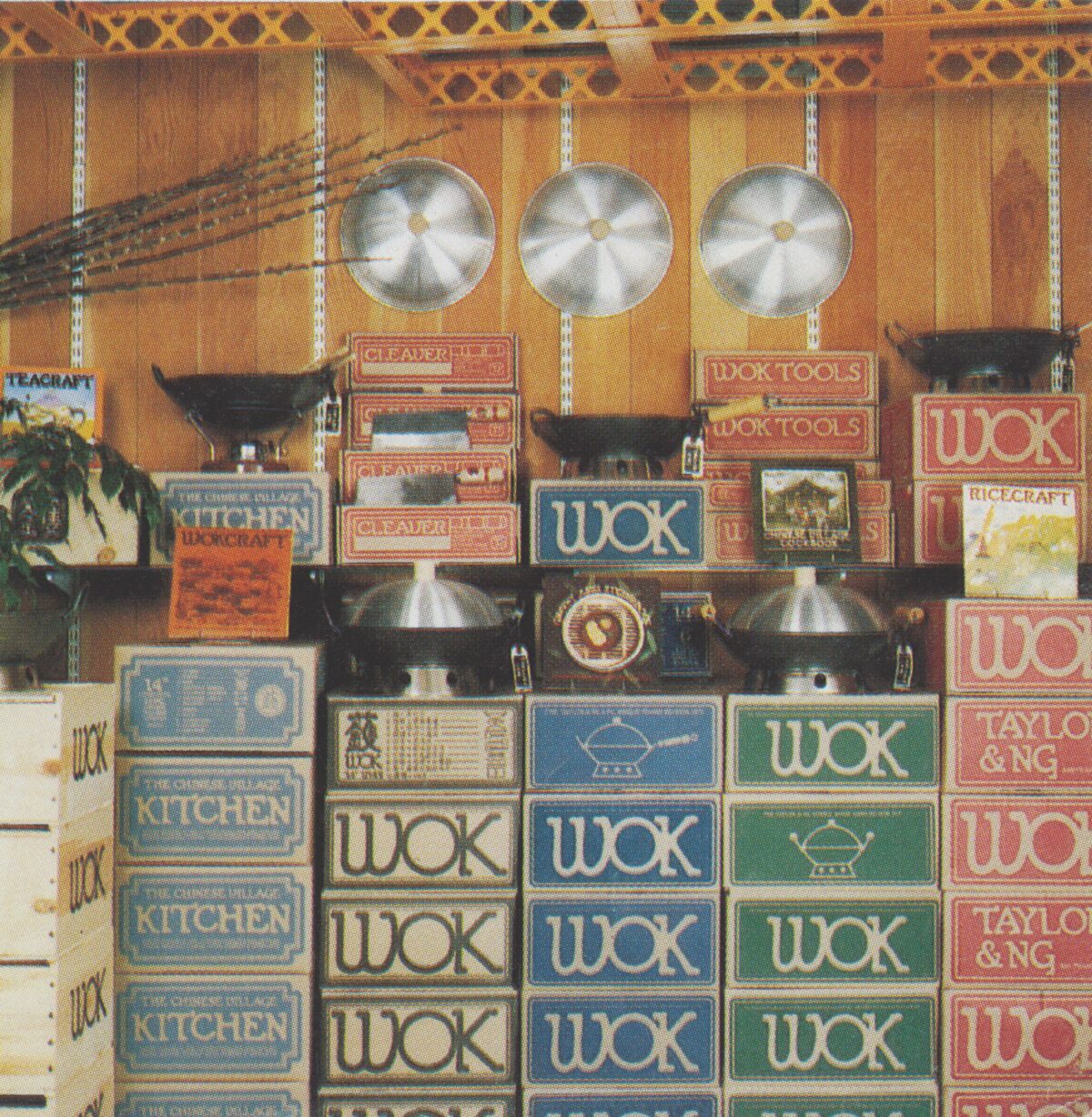

Their wok was another well-timed product release. In 1972, just as President Nixon’s visit to China reopened trade and travel after a twenty-two-year embargo, the company’s wok hit the market, with a wooden handle and a unique domed lid. The wok and its accessories—a steamer basket, tongs, and a spatula—were tidily packaged in a brightly colored cardboard box with Wokcraft, a how-to book of recipes by the Schafers, promising to demystify wok cooking and maintenance. While the individual components of the set weren’t hard to find in Chinatown kitchen supply stores, the kits in their charming boxes made it easy and appealing for the American consumer to get into wok cooking, especially once they were wholesaled to major department stores. At one point, the company’s Far East Housewares Collection—including woks, cleavers, teapots, a calligraphy set, and a tempura kit—brought in 50 percent of the company’s revenue. The wok, of course, had been around for centuries—Taylor & Ng didn’t introduce anything new, but it was part of a wave of retailers and chefs in the 1970s who were popularizing Chinese cooking with mainstream, Western audiences. Its peers included the Wok Shop, which opened in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1969 and still sells American-made woks from its original location; and Joyce Chen, a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based chef with a popular cooking show who patented a flat-bottomed wok to better fit contemporary electric stovetops.

In 1973, Taylor & Ng opened a second, larger retail location directly across the street from the original Howard Street store. Between 1974 and 1979, Taylor & Ng closed the Howard Street stores to open three others in more prime locations: in Palo Alto, California; on Market Street in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood; and in a little kiosk at Macy’s in New York City. In 1979, they opened a three-level, eight-thousand-square-foot flagship location in the Embarcadero Center, in the heart of San Francisco’s financial district. They had arrived.

Even as the business grew, Win continued his hyper-productive dedication to the fine arts. His art star had risen early; he had received notable awards for his work in ceramics as a high school student. In his twenties, he had shown his work at prestigious arts institutions throughout the US and Europe, and had solo shows in New York and San Francisco. Gallerist Ruth Braunstein referred to him as “the hot star.” His tenacious work ethic and media-agnostic, intuitive process propelled a dynamic art practice. “Work is a pleasure,” the twenty-five-year-old Win Ng told the Examiner in 1960.

Though it’s common today to be a potter-poet, a painter-builder, or a writer-musician with a day job, the art-world establishment at the time didn’t quite know what to do with Win’s multi-hyphenate approach to creative work, especially when he turned toward commercial mass production. Many artists must find additional sources of income to pay the bills, but this reality is rarely discussed, celebrated, or included in a holistic rendering of the artist as a complex human being living under capitalism. Win’s siblings said he was always entrepreneurial, and had sought opportunities to make a living through his art since he was a teenager.

The few existing artist profiles about Win describe his “departure” from fine art or his “pivot” into business, but it was really more of an expansion: he continued to make and show sculptural ceramics and later experimented with large-scale public commissions, even as the plates and bowls rolled off the production line. Carlos Villa recalled, “He was maybe the richest guy in the school, because people were either buying his work as fine art or buying it because they needed a perfectly matching set of plates and wares.” His first solo show, at age twenty-five, was in 1961 at the Mi Chou Gallery on Madison Avenue in New York, only one year after he started Taylor & Ng. The show flyer boasted of Win’s “honest, humorous, ambitious, and energetic” works that “reflect the artist’s true self.” In 1964, as the chicken cooker production was moving to Japan, Win’s show of ceramic sculptures at Braunstein’s Quay Gallery in Tiburon, California, received a write-up in Artforum—an achievement that remains a benchmark for “making it” in the art world today. He was wildly productive, agnostic of medium or context.

In 1968, shortly after the opening of Taylor & Ng’s first retail shop, Win began a period of public art commissions, his first being a colorful ceramic tile mural for the front of the Maxine Hall Health Center in San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood. During a recent renovation, the mural was preserved and expanded onto a new face of the building. Spaulding assisted Win with works for several public parks in Sunnyvale, down the peninsula, including a chunky, concrete, Flintstones-esque playground structure with rounded edges, a large pond, a sculptural steel water feature, and a fountain pavilion of little concrete mountains that later became known as Fish Banks, a popular skateboarding spot in the 1980s. Spaulding had no recollection of how Win got the public art commissions. “I don’t know that he was applying for them, but he was getting them,” he said. In 1971 in Orinda, a wealthy suburb of Oakland, Win painted a mural at the new BART station. Today, his supergraphics-like mural of bold, geometric orange, black, and white stripes is chipping, peeling, and scuffed. Jennifer Easton, the current art program manager at BART, said she hopes to restore the piece in the next year.

Win explored mediums, context, and scale, following his intuition and seizing opportunities as they arose. Spaulding didn’t think Win ever considered there to be a division between fine art and commerce. Mimi said, “He saw the opportunity to make money, and that was a draw,” considering the circumstances of his upbringing. She added, “He probably felt he would get back to it.” As Allen wrote, “It is well to note that it is a Western, not Eastern, point of view that denigrates utility and makes the distinction between ‘craft’ and ‘fine art.’”

What began as Win and Spaulding’s side hustle to fund their fine-arts practices exploded into a wild success, and became their focus for decades. As the two approached their business with a sense of whimsy, and worked together to create a rich, layered, nuanced brand identity, it’s clear Win considered the company to be simply another opportunity for artistic expression.

The Taylor & Ng retail stores were an experiment in experience, offering the consumer an immersive, aesthetic encounter. “We looked at retailing from the artist and craft type of approach,” Win said in a 1979 Examiner article. “We were never satisfied with the environment in which our merchandise was placed—just our own quirk.” They arranged products like art in a gallery or museum. Mimi, who worked at a number of the retail stores, said, “He was quite particular. He would always be there, ditzing around.” International crafts imports intermingled with studio ceramics on bespoke shelves designed by Win and built by Herman. Bright screen-printed boxes were stacked into large floor displays. Spaulding loaded the top shelves with houseplants, at first to fill empty shelves after they had sold out of inventory, and later just because he liked the way they made the space feel.

Taylor & Ng served chrysanthemum tea at its stores. It sponsored an egg-decorating contest each Easter, with prizes for adults and children. Its weekly newspaper ads offered giveaways and “This week only!” deals. It hosted wok demonstrations—some hosted by the young, then unknown chef Martin Yan—at high-end department stores like Macy’s and Gump’s to help people visualize cooking with a wok at home. This type of integrated marketing may sound rote in today’s post-retail landscape of internet shopping, where social media floods our attention with advertisements disguised as “content” for one lifestyle brand after another. But at the time, consumer culture was still young, with fledgling postwar shoppers just beginning to associate their consumption with their identities. Mainstream television and magazine advertisements pitched products, not lifestyles. Taylor & Ng was selling the whole package: taste, objects, function, the feeling of a dinner party, and the idea of being a worldly collector without going farther than the shop down the street. “We’re not here to set a style,” Win said in an Examiner article. “We’re here to offer basic things, a mix, a range, so that the homeowner can create his own space.”

Taylor & Ng also fit into a growing gourmet kitchen zeitgeist, alongside enterprises like Williams Sonoma, which opened its first San Francisco shop in 1958, selling French cookware. Crate & Barrel started up in Chicago, dealing in imported kitchen goods. Julia Child’s cooking show The French Chef first aired on public access television in 1962, bringing a new kind of gourmet into homes across America. These folks all met and mingled at the same trade shows. As Win’s family and Spaulding told it, they were leading the way in innovative product design and merchandising, and a lot of companies flattered through mimicry. Herman remembered seeing the interior of a Williams Sonoma store in San Francisco and thinking that its wooden shelving looked familiar. Though the fern bar aesthetic later became widespread, Spaulding says he was the first retailer he knew to create lush jungles of tropical-houseplant interiors. With the rise in popularity of Plantcraft, Taylor & Ng began to propagate houseplants offsite at a greenhouse-roofed building on Harrison Street.

Taylor & Ng did not operate in a vacuum, nor was it the most successful home-goods business in the long term: Williams Sonoma went public in 1983 and today operates over five hundred stores between its many sub-brands, which include Pottery Barn and Rejuvenation. But the company’s unique offering was the alchemical union of Win’s and Spaulding’s creative sensibilities, drawn from their cultural context as gay artists in postwar San Francisco.

At the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society’s archives in San Francisco, there is a manila folder labeled “Party at Win Ng’s House, 1985.” Within are images taken by Robert Pruzan, a photographer and mime who diligently documented the city’s gay scene in the 1970s and 1980s. I browse the contact sheets with gloved hands, encountering a puzzling dichotomy that seems to be entirely appropriate for a party at Win’s. In the first images, elderly Chinese party guests are seated cozily around a sparsely decorated living room. In later images, two hunky dudes pose nude in a round redwood hot tub.

Win was known for keeping his personal life private. Despite San Francisco being a queer mecca, the gay civil rights movement didn’t fully blossom until the very end of the 1960s, and before that, gayness was somewhat of a liability in public life. Win’s sexuality was a bit of a public secret: known to most, but not officially acknowledged. Allen Hicks, in the retrospective catalog, wrote that Win “chose not to ‘come out.’” On the other hand, Spaulding’s husband, Tony Manglicmot, said, “I mean, everyone was out. Everyone knew about everyone else being gay.” Win and Spaulding were referred to as “partners” in the press, but always vaguely or in relation to their business. He skillfully evaded reporters’ questions about his personal life, saying work was his priority. Spaulding told me they were gay and that was that. “It was a matter of fact,” he said.

Both Win’s family and Spaulding said he never participated in gay rights activism. Michael Hunter, the queer studies scholar and tenant from Win’s house, suggested that, perhaps due to Win’s age and tendency toward privacy, he wasn’t interested in activism; he was forty in 1976, older than many of the young men flocking to the Castro, the city’s gay center. “Merce Cunningham and John Cage were very similar,” Hunter told me. “They weren’t interested in identity being part of their work.”

Win was diagnosed with HIV in 1982. According to Allen Hicks, he was one of the first people in San Francisco to receive a diagnosis; the AIDS crisis had begun just a year before, in 1981. Each person I speak to about Win’s illness bemoans the fact that it wasn’t until many years after his diagnosis that the FDA approved lifesaving antiretroviral drugs, which today remain the only way to treat AIDS. Win was characteristically private about his diagnosis, and many of his family members were unaware of it until he began showing symptoms, in the late 1980s.

San Francisco was an early center of the AIDS epidemic in the US and for many years had the highest per capita rate of cases. Then mayor Art Agnos described it as “the biggest human tragedy in the modern history of this city.” The hollowing-out of San Francisco’s gay community by the AIDS epidemic had a palpable impact on the city’s culture, and Spaulding and Tony told me this time of massive change also caused a major shift in the character of the company. “I think a lot of that… youthful energy that was part of Taylor & Ng kind of got lost during that period,” Tony said. “Selling the lifestyle ended when the designers were no longer there.” He told me that many of the designers for the company ultimately died of AIDS.

In 1983, just four years after opening its downtown flagship store, Taylor & Ng closed its retail locations and turned its focus to wholesale. The same year, Win left the day-to-day operations to return to his studio art practice; Spaulding had left the business in 1980. Natalie and Norman divorced, she left as well, and Norman took the helm. Win contributed the occasional illustration—for a holiday mug or tea towel—but focused in earnest on the creation of works for the gallery.

With time to spare, Win reactivated his half of the Belcher Street warehouse he co-owned with Spaulding, renting studio space there to other artists. In 1985, he presented a solo exhibition of ceramic sculptures, returning to show with Ruth Braunstein. The works were slab-built combinations of circles and squares, bright jewel-tone glazes applied in a quilt-like pattern. The exhibition’s press release suggests that the works “exemplify the serenity and the maturity of time.”

Win had the support and care of his family in his final years, something many other gay men dying of AIDS did not have. Norman handled the business operations, and Herman drove Win around for errands. Mimi visited him in the hospital often. “We were there all the way to the end,” Herman said.

Win died in 1991 from AIDS-related complications, after living with the illness for nearly a decade. He was fifty-five years old. As he became weaker toward the end of his life, he abandoned ceramics in favor of painting, working in acrylic and oil on different series that diverged aesthetically and materially from his previous work.

One piece from his late-life experimentation with oil painting hangs in the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. Natalie commissioned Win to paint Natalie’s Jungle in 1989, and donated it to the museum in 2022. It is part of the same series as the unfinished jungle painting that hangs in Alice’s house, though this one is brimming with life, each animal turned to look right at you with its eyes wide open. I stand before the sixteen-foot-tall painting in a chilly museum on a 105-degree summer day, looking for the weird little creatures hidden within it: a cat-fish with tabby markings, a hippo with a snail as its eye, a flamingo standing on a turtle, a monkey with a tiny banana. I wish this painting had a ladder alongside it, so I could look more closely at the phoenix, floating in the air at the top of the canvas: a mythical bird that can be born again after death.

I’ve spoken with Win’s family, and I have plenty of facts. I have dates, and addresses, and the oft-repeated narrative of his rise to success. Each person tells me he was funny, and worked hard, and was generous. I ask for more: What was it like when he walked into a room? What was it like to collaborate with him? I hear similar stories repeated from different angles: Win was a terrible driver. He liked to make lists. He usually had a long, dark cigarette dangling from his lips. He had a dry wit, they said. I have encountered this challenge within my own family: It is difficult to speak about someone you’ve lost, especially decades later. And not just because it’s painful, but because memory is strange and things fade. A person can become enshrined in lore. The stories that are repeated are the ones that stick around.

Ally said she has a fantasy of an alternative world in which her uncle is alive, they are friends, and she works alongside him at Taylor & Ng. I, too, have a fantasy of what it would be like if Win were still alive: I’d be sitting in his living room right now, my socked feet on the parquet floors, asking him questions, through a cloud of smoke, about his life and decades of work. Since I can’t call Win, I call Spaulding Taylor, and hope he will invite me over. He does.

Spaulding and Tony live north of San Francisco in Sonoma, on a lush one-acre compound they designed and built. They left San Francisco tentatively after Win’s death, thinking they’d split their time, but over the years their center shifted.

We sit at a large wooden table in their kitchen—which is not in their small home but in the massive adjacent studio building—with its large doors open to the sunny courtyard, a glittering pool at the center. Paintings cover the walls. I see a kiln in the corner, and an open bag of clay sitting on a worktable. Spaulding tells me he is losing his sight, so he works in clay more and paints less. His recent pieces rest on a homemade plywood shelf on wheels: raku-fired bowls of all sizes dressed in drippy, glimmering hues.

They walk around, pulling things to show me from drawers and shelves. Spaulding holds an original Win drawing, ink rendered in the smallest brushstrokes on rice paper, careful and delicate. I ask if they have any of the earliest studio ceramics. Tony exclaims, “The plates!” and rushes over to a cupboard to pull out a stack of stoneware plates from the Folsom Street studio days. They feature Win’s freestyle illustrations, painted in earthy glaze: a topless woman with voluminous hair, a lion, a cat fishing. I’m relieved to see these objects, because Spaulding and Win were not precious about maintaining an archive. In 1979, they told the Examiner that they had few of their early works. “I didn’t save any of them,” Spaulding says, “but we found some in other people’s garages.” Win adds: “I found one of my early ashtrays at the Salvation Army.”

We speak for hours, and they tell me what they remember. The general arc is clear, but some of the details are fuzzy; it’s been more than forty years since Spaulding left Taylor & Ng, and more than thirty since Win died. “It’s a very strange thing,” Tony says, about losing friends during the AIDS epidemic, “especially now that Spaulding is ninety and I’m seventy-one. It’s like a time capsule: all of these people got put in, and they’re all stuck in this time period, while we’ve moved on.”

Though he may be enshrined in the memories of his loved ones, and though his work lives in many households, Win Ng is far from a household name. He is mostly missing from the history books that survey Bay Area art. While his early work is in museum collections, he hasn’t had a large, solo retrospective show at any major institution, nor has his distinctly creative retail merchandising, curatorial importing, or product design work with Taylor & Ng been recognized or showcased. Many of the details on his Wikipedia page are incorrect.

In the same vein as most written history, the art-historical canon is largely oriented toward white male artists, and skims over everyone else. I was stunned to learn that even the Asian Art Museum did not present a solo exhibition of an Asian American artist’s work until 2014. In the last ten years, it has presented retrospectives featuring Carlos Villa, a Filipino American visual artist, and Bernice Bing, a Chinese American lesbian painter—both former classmates of Win’s at CSFA. I wrote to the museum to inquire about any potential plans for a Win Ng retrospective, but didn’t receive a reply.

Today, Taylor & Ng is owned by Ally’s other uncle, her mother’s brother Victor Moye. In 1994, Norman got sick and couldn’t keep the business afloat. By 1997, Taylor & Ng had filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy. Victor attended the auction and outbid two others. At the time, the company had no inventory warehouse, so he purchased the brand, its relationships with manufacturers, and its intellectual property. Today, its website sells woks, reproductions of some mugs, and miscellaneous imports.

Just inside the front door of Win’s house, there’s a redwood door to the garage. Ally and I peek inside. On one of the shelves, printed on the side of a box containing a set of deadstock tableware, I see Win’s familiar illustration style: a 1976 drawing depicting a lively multigenerational gathering in a living room with an enormous window overlooking trees outside. Each smiling person holds a plate of food, a spoon, or a stack of dishes in their hands. One man pushes a rolling cart loaded with a Taylor & Ng feast: a roast pheasant, a soup tureen, a teapot, and goblets for wine. Cats, dogs, and pet bunnies lie about. A glimpse into the kitchen reveals pots hanging from a rack and a wok and a ceramic chicken cooker on the counter. Houseplants are all around; there are paintings on the walls; it’s a joyful living tableau. The environment is filled with ceramics, “animating the scene around the house.”

It’s a scene I can imagine taking place upstairs, in Win’s living room: any number of his seven siblings, serving themselves hot food cooked by their parents on the six-burner stove. Partners, nieces, nephews, and pets. Spaulding arrives to drop Win off and stays for dinner. The chatter of a close family—siblings, business partners, neighbors, housemates—rises into a cacophony mixed with the clink and clatter of forks on plates, the hiss of steam from beneath the wok lid.