Photograph of Bruce LaBruce by Maxime Ballesteros

An Interview with Auteur of Pornology, Bruce LaBruce

“Now raise your hand up out of the grave. That’s it. Raise it as a protest against all the injustices perpetrated against your kind. Raise it in solidarity with the weak and the lonely and the dispossessed of the earth, for the misfits and the sissies and the plague-ridden faggots who have been buried and forgotten by the heartless, merciless, hetero-fascist majority. Rise! Rise!” So declares Medea Yarn, the strident radical filmmaker in Bruce LaBruce’s film-within-a-film, Otto; or, Up with Dead People (2008).

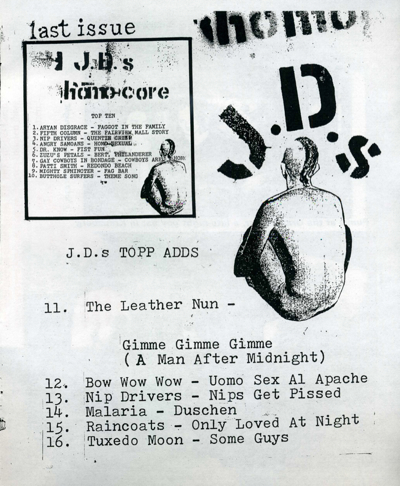

A zombie-political-porno, which, like most of La Bruce’s work, arouses, amuses, and repels at once, Otto is an incisive critique of gay consumer culture, and its mindless assimilation of bourgeoisie values. The critique has remained fundamental to the director’s queercore aesthetic since the mid-1980s, when BLAB (the artist’s chosen acronym) developed his prescient queer punk zine, J.D.s (co-edited with G.B. Jones).

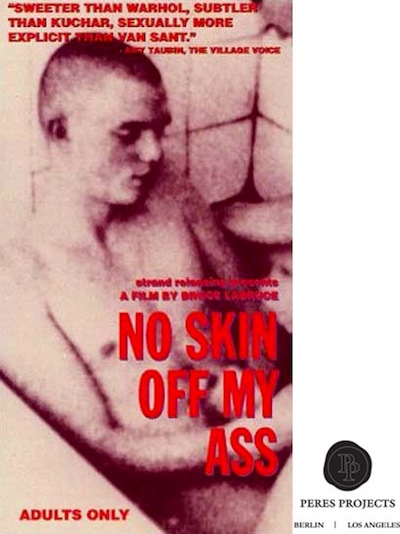

Not surprisingly, his first feature films, No Skin off My Ass (1993), Super 8½(1993), and Hustler White (1996), with their B-movie depictions of taboo desire, from a skinhead fetish to gang rape and amputee sex, cemented BLAB’s cult status as the reigning daddy of queercore film. That they also conjured the anarchic ideals of writers like Georges Bataille and Jean Genet, who similarly viewed sexual deviance as political transgression, was of course lost on many, but their trademark mix of high and low, of emotional tenderness and abject fetish, still registers as mutiny.

Certainly, anyone looking for the money shot pleasures of commercial porn will be disappointed. BLAB thwarts as he titillates for the same reason he reflexively calls attention to his medium, mashing up genres and referencing other films: to challenge our expectations, and force us to consider our spectatorship.

The trope of the social outcast in later films—be it vampire, prostitute, vagabond or terrorist—functions in much the same way, as what initially provokes our disgust often begets our (eventual) sympathy. Ironic, then, that his notoriety comes from his reputation as a pornographer, when he’s a provocateur first and foremost. True subversives, though, often function as Trojan horses, their weapons necessarily concealed. No wonder his Cuban husband calls him, half-jokingly, Brucito Subversivo—a moniker which, if not as Warholian as his elected name, evokes the same provocative irony.

Angélique Bosio’s aptly titled documentary about BLAB’s life and work, The Advocate for Fagdom (2011), traces the origins of his identification with “the misfits and the sissies and the plague-ridden faggots” from his rural upbringing as the son of farmers in Ontario, Canada to the identity politics of his film school years—both experiences he found equally alienating. In fact, many of his films satirize the totalitarian tendencies of the politically correct, exposing their hypocrisies with the same campy vigor reserved for the right wing ideologues (and gay assimilationists). To this end, the line between homage and satire can get very blurred, which is what makes his films, as Gus van Sant points out in Bosio’s doc, so complex, and yet purposely crude. The Raspberry Reich (2004), with its parade of cheeky, nonsense slogans—"The Revolution is my boyfriend!“, “Cornflakes are counter-revolutionary!”, “Fuck me for the Revolution!"—is a perfect example.

Titled after both the communist sexologist Wilhelm Reich and a term coined by Gudrun Ensslin (leader of the infamous 1970s German terrorist group Red Army Faction) to designate the tyrannical consumer society, the story imagines a contemporary version of the group, led by a sixth-generation Gudrun who calls her comrades to action in The Homosexual Intifada. Heterosexual herself, she declares that masturbation is counter-revolutionary, and commands her followers to fuck each other publicly (though one manages to jack off in front of a giant poster of Che Guevera in a controversial scene that offended many).

It’s a sly dance in the slipstream between revolutionary ideals and their compromised practice, and a slapstick study in “radical chic.” BLAB explains: “The problem with working within the capitalist system by making these radical political movements alluring, and even sexy, is that it plays into what Marx called commodity fetishism.” When the group of avowed vegans goes through a Burger King drive-through, the kidnapped son of a wealthy industrialist in the trunk, the parody is complete, and as with all BLAB’s work, the explicit sex is never an end to itself.

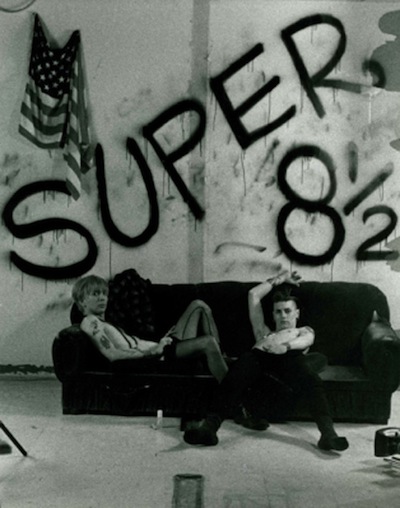

Frequently, elements of the autobiographical are conflated with campy pornographic story lines openly culled from other sources, employing the strategy of détournement to recontextualize their meaning. Super 8 ½ (1993) is the most obvious instance of this, featuring a failing triple-X director named Bruce that parodies Fellini’s 1963 masterpiece, a semi-autobiographical comedy-drama about a filmmaker in creative crisis. A poster from Warhol’s Blue Movie (1969) and clips of Elizabeth Taylor from Butterfield 8 (1960) round out the film’s self-conscious quotations, which the platinum-banged, sunglass-wearing protagonist cheekily celebrates in his declaration: “There’s no copyright on a good line. When I used to direct pornos, I’d steal titles, dialogues, entire plots. Everything came from other movies.”

Bruce LaBruce, Super 8 ½, 1993

If Super 8 ½ is also a campy rebuke to the notoriety of early films, particularly critics unable to reconcile BLAB’s hardcore, B-movie aesthetic with his complex political and avant-garde leanings, recent films like Gerontophilia (2013) and Pierrot Lunaire (2014) offer a more subtle redress. So much so that, in an ironic turnabout the artist will no doubt exploit in some future film, these works have been interpreted as evidence that BLAB has gone soft.

The interview that follows attempts to explore these reactions as well as the films themselves, and their place in BLAB’s evolving legacy. As fellow filmmaker and friend John Waters points out, regardless of what others may think, Bruce LaBruce is an auteur, perpetually ahead of his time. As such, his “pornology,” a term he devised to distinguish his work from pornography, will never achieve mainstream success. Queercore to the end, his films’ celebration of sexual deviance, social misfits, subversive love, and all things politically incorrect refuses that aspiration anyway, standing instead as testament to film that can’t be packaged for the masses. Vive la révolution!

—Jane Harris

I. FIGHTING AGAINST NATURE

JANE HARRIS: With films like Super 8 ½, Hustler White and Skin Flick/Skin Gangs, you became quite infamous for controversial pornographic, queercore storylines involving necrophilia, neo-Nazi skinheads, etc. While these films were complex allegories for political and social commentary, many critics missed this aspect in the face of their more disturbing and salacious aspects. While being about taboos, the films became taboo. Your recent work seems to have moved away from such overtly provocative and explicit narratives. Were you trying to avoid more (mis)interpretation/negative reception?

Bruce LaBruce, courtesy Peres Projects

BRUCE LABRUCE: No, not at all. In fact, Pierrot Lunaire, a film I made concurrently with Gerontophilia, has a controversial "queercore” storyline with a bit of pornographic content. It’s an adaptation of Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, which itself is a kind of precursor to “queercore” inasmuch as it is an atonal work, radical for its time, with very violent, disturbing imagery provided by 21 poems by Albert Giraud. The male character Pierrot is always played by a woman, lending it a subversive and modern gender twist. This is why I applied to it the true story of a female-to-male transsexual, who serves as a kind of allegory for all gender radicals and outcasts driven to extremes by the disapproval and hostility of the dominant order. For me, Pierrot Lunaire is quite consistent with my previous work. With Gerontophilia, I also chose a character—a young man with a fetish for the elderly—who goes against the grain of society, but I approached it in a more strictly romantic and somewhat mainstream narrative style to make it more accessible to a wider audience. But for me, the message of the film is still subversive, even using a more gentle and subtle approach.

Bruce LaBruce, Pierrot Lunaire, 2014

JH: Both Gerontophilia and Pierrot Lunaire are tragic love stories (ending in death and rejection respectively). In both films, the main protagonists (a young man in love with his elderly male patient and a transgender male in love with an unknowing cis female) are, as one character in Gerontophilia puts it, bravely and radically “fighting against nature.” Can you talk more about this shared theme and how it reflects your ongoing interests in exploring cultural taboos to expose capitalist-homophobic machinations?

BLAB: Camille Paglia has pointed out that in terms of homosexuality, not everyone is prepared for a daily struggle against nature. In some ways, people who challenge and subvert their biologically-determined body are struggling against nature. It’s a mysterious combination of nature and nurture that determines a person’s gender, and for whatever reason some people are driven to challenge their biological “destiny”. It’s a difficult struggle, and I believe it takes a lot of courage. Other people merely question or challenge the culturally-determined conventions of gender and sex roles, which is also a kind of valiant struggle. In terms of capitalism, there is a tendency under this system to reduce everything to a kind of commodity fetish, and this order tends to promote extremely conventional and uniform expressions of gender and sexuality in order to promote certain products and lifestyle choices that are commercialized and packaged under a corporate system. This necessarily entails a capitulation to heteronormativity, or in the case of the new gay movement, a “homonormativity” that doesn’t stray far from the heterosexual paradigm. Anyone who questions these normative values and conventions is subject to disapproval, hostility, or even violence.

JH: In refusing such value systems, your films have underscored an anti-assimilationist stance, a fundamental aspect of queercore culture that you helped define in the 1980s. Do you think this stance is still active in the newer work, which you describe as reflecting a “somewhat mainstream narrative style” and a “more gentle, subtle approach?”

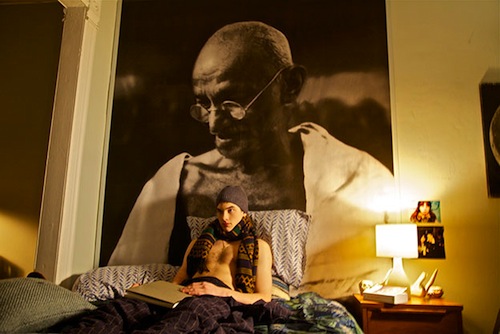

Bruce LaBruce, Gerontophilia, 2013

BLAB: Yes, indeed. I made Gerontophilia using a different method and in a different style from my previous work, but it is still totally consistent with the themes and belief system that I have always conveyed. The film is about an eighteen-year-old boy who is not gay-identified, but who nonetheless develops an intimate and sexual relationship with a much older man. But he is also portrayed as a kind of serial gerontophile who has had sex with other old men and will obviously continue to do so after the death of his love object, Mr. Peabody. The fact that he is a gentle and empathetic character actually makes his fetishistic behavior seem loving and romantic, which is a theme that runs throughout my work—people who exhibit extreme or unorthodox sexual behavior can also be affectionate and kind-hearted. Lake, the young man, transgresses barriers of race, class, age and sexual orientation to pursue his fetish. In that sense, he is a kind of gentle and conscious revolutionary, or, somewhat ironically, a saint. His girlfriend, Desiree, also has sex with an older man (her boss) and with another girl. Furthermore, Lake’s mother has sex with her boss, and then with Peabody’s son, who is black. The gentle nature of the film doesn’t preclude the idea that these characters are behaving sexually in ways that challenge societal norms.

II. SINCERITY AND SARCASM

JH: Allusions to sainthood, as a kind of ascendancy, are made in both films. Lake insists several times “I am not a saint” in Gerontophilia, and in Pierrot Lunaire, after presenting proof of his manhood—a cock obtained by violently castrating a taxi driver—to his horrified love and her father, the protagonist becomes “SAINT PIERROT”, thus ending the film. What is the significance of these allusions, and how does this trope function for you?

Bruce La Bruce, Gerontophilia, 2013

BLAB: For me, images of sainthood and martyrdom are a direct expression of those same valiant individuals I’ve mentioned who challenge the status quo and go against the grain of culture and biology. In the case of Lake, the young man in Gerontophilia, his sexual fetish for the elderly is partly an expression of his empathy and love for old people who have been marginalized, abandoned and forgotten by society. His empathy translates into a sexual expression of love and tenderness. In this sense, he is a kind of saint. In his drug-induced fantasy, in which he licks and kisses the bedsores of the old man, he is associated with the saints of bygone eras who sucked the poison out of the sores of lepers. In Pierrot Lunaire, it was important for me to present Pierrot as a kind of martyr to the cause of gender radicalism. The true story it was based on happened in 1978, before a real consciousness of transgender rights emerged. Because of the strict and repressive rules of gender identity, he is forced to conceal his biological gender, and when he is found out, his sexuality and the object of his desire is denied to him. He is driven to a kind of madness by the hostility and repression forced upon him, and he acts out violently against his oppression. Representing him as a martyr, or, somewhat ironically, as a saint, is an acknowledgment of his persecution and of the untenable position a repressive society places him in.

Bruce LaBruce, Pierrot Lunaire, 2014

JH: The scene in which Lake licks and kisses the bedsores is pretty campy too, the crescendo of scary music that accompanies it nearly cueing the audience to laugh. Humor, of course, has been essential to your work, especially where blood and gore is concerned, and yet Gerontophilia, though brilliantly funny, seems less nihilistic in tone. Would you say you’re mellowing with age?

BLAB: Happily, no. When you make one movie that is a radical departure, at least in outward appearance, from your previous work, people tend to want to impose a narrative on you: that you’re going in a new direction, that you’ve gone soft, that you’ve mellowed. Pierrot Lunaire was made after Gerontophilia, and is another low-budget, sexually explicit, violent, and disturbing film. It’s presented as a fractured narrative, repetitive and imagistic, referencing the conventions of silent film. It’s also a harsh tale about an F-M transsexual who acts out violently and shockingly against the oppressive heteronormative culture that rejects him. Strangely enough, like Lake, Pierrot is portrayed as a kind of saint or martyr, but the style and mood of the film is much, much darker.

Bruce LaBruce, Pierrot Lunaire, 2014

JH: Returning to your relationship to camp again for a moment, your witty 2012 revision of Susan Sontag’s influential 1964 essay, “Notes on Camp” (“Notes on Camp/Anti-Camp”), undermines her claim that camp is essentially an “apolitical” and “disengaged” sensibility. You do this by developing new subcategories for the term—“straight camp,” “bad conservative gay camp,” “ultra-camp,” etc.—that you illustrate with characteristically irreverent examples (Madonna is bad straight camp). In an interview for Huffpost, when asked what category you fell into, you answered, “classic camp,” which you inferred was "a signifying practice invented out of necessity (both for survival and for sheer creative pleasure).” Can you talk more about how your work engages notions of camp as a political aesthetic, and what makes it "classic camp”?

BLAB: Much of my film work is classic camp inasmuch as the actors, quite often non-professional actors, play versions of their authentic selves in an obviously performative style. Also, the movies themselves are highly stylized, super-referential, and full of distancing techniques that make the viewer aware of the dynamics of spectatorship. I have an appreciation for what some people would call “bad acting,” but which I think can be much more real than the overly emotive, technical and supposedly "realistic” acting that is so prevalent in mainstream cinema. I also quite often use queer archetypes and scenarios that play into ideas of fetish, porn (which is often itself very camp), and fashion (ditto). Politically speaking, I create narratives that celebrate the outsiderness and otherness of homosexuals or transsexuals, and I use references and signifiers that are sometimes so deeply coded in homosexual or “queer” tropes that they may be difficult for the average viewer to decipher. Finally, my films often have a very strong strain of irony, or even sarcasm, which is definitely related to homosexual camp. But it is by no means straightforward: quite often I am sincere when I appear to be sarcastic, and I am sarcastic when I appear to be sincere. I also try to contradict myself at least once a day, which is a camp must.

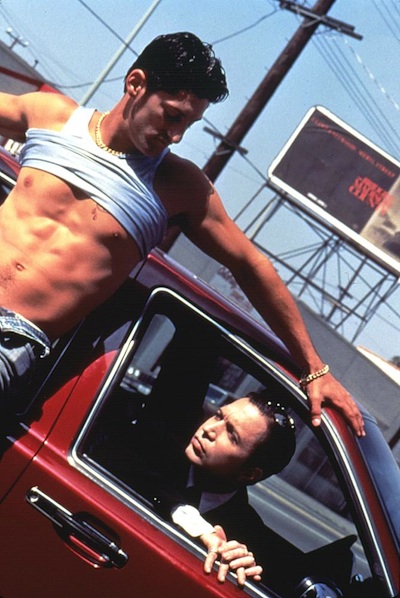

Bruce LaBruce, Hustler White, 1996

III. AMBIGUITY AND AMBIVALENCE

JH: Very often you work from existing references, namely films, which you adapt and pervert to various ends. Why do you think this has been such a key aspect of your process?

BLAB: I have always been first and foremost a cinephile, so making references to other films is second nature to me. I also went to film school in the eighties during the rise of postmodernism, so hyper-referentiality was very much part of the academic discourse. However, I also rejected the major tendencies of post-structuralism, and maintained a certain grounding in social and political realities, which included feminist and Marxist leanings and a gay militancy that questioned authority and the capitalist status quo. One of my projects with my films has always been to effect a certain kind of “detournement,” borrowed from the Situationists, to borrow or steal from other narratives and texts and “homosexualize” them, or turn them against their original intent in some way. With The Raspberry Reich, for example, I presented the signifiers and icons of revolution, which have been emptied of radical meaning or impetus by capitalist exploitation, and recontextualized them in terms of homosexual radicalism or pornographic signification. It’s a strategy that is presented both sincerely and ironically, which adds a level of ambiguity and ambivalence to the films.

JH: There’s certainly a lot of secondary references that only a cinephile would catch. For example, Otto; or, Up with Dead People, while obviously a nod to zombie films, is also a tribute to Maya Deren’s experimental gem, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). How essential is it for your ideal audience to get these obscure references?

BLAB: It’s true, many of my films have been narratives stolen and patched together from other films. No Skin off My Ass is a remake of Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park; Super 8 1/2 references Fellini’s 8 ½ and Frank Perry’s Play It as it Lays; Hustler White mashes up Warhol’s Flesh, Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, and Aldrich’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, etc. It’s significant inasmuch as quite often my movies “queer” these narratives and reconfigure them in a more politically charged context, often drawing attention to the latent homosexual subtext in classic texts.

JH: If you could correct any misconception about you or your work, what would it be?

BLAB: Certain viewers and critics are a bit surprised by the “tenderness” and “romanticism” of my new film, Gerontophilia, but that tendency has really been in my films all along, even in the ones that are overtly pornographic and/or violent. One thing I try to do with my work is to show that people who have extreme fetishes or who exist outside the constraints of “normal” society still have romantic impulses and are capable of love and tenderness. Sometimes people cannot or don’t want to acknowledge that pornographers are people too!

Bruce LaBruce, Gerontophilia, 2013

JH: Can you tell us what you’re working on next?

BLAB: Next I will be making another art film about feminist revolutionaries called Ulrike’s Brain. It is a sequel of sorts to The Raspberry Reich. I am also developing another bigger, more narrative movie that is also based on a fetish. Also, later this year I will be releasing my very own perfume, called Bruce LaBruce’s “Obscenity”!

Bruce LaBruce, photographs from exhibition, Obscenity, 2012, LaFresh Gallery, Madrid

Jane Harris is a Brooklyn-based writer whose writings have appeared in publications from Art in America and Artforum to Time Out New York, and the Village Voice. She has also contributed essays to various catalogues and monographs such as Hatje Cantz’s Examples to Follow: Expeditions in Aesthetics and Sustainability (2010); Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art Carla Gannis (2008); Phaidon’s Vitamin P: New Perspectives in Painting (2004) and Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing (2005), Universe-Rizzoli’s Curve: The Female Nude Now (2004), and Twin Palms’ Anthony Goicolea (2003). She is currently at work on the book After: The Role of The Copy in Modern Art. Ms. Harris is a member of the art history faculty at School of Visual Arts, and also curates (a recent exhibition, Crazy Lady, 2011, received positive reviews in Time Out New York and Huffpost). She is the founder of the blog(zine), janestown.net, and a sample of her fiction can be read here.