Ann DeWitt on Annie Leibovitz’s Photographs of Susan Sontag

In Greek mythology Proteus was able to change shape with relative ease—from wild boar to lion to dragon to fire to flood. But what he found difficult, and would not do unless seized or chained, was to commit to a single form, the form most his own, and carry out his function of prophecy.

— Marvin Israel, Birthday Card to Diane Arbus, 1971

In 1973, Susan Sontag said of the nation’s increasing obsession with photography, “Kodak put signs at the entrances of many towns listing what to photograph.”[1] Sontag’s own life could have populated a town and had its very own sign. But in 1973, America’s focus was on other landscapes. As Sontag notes in On Photography, photographers, laymen and otherwise, were capturing images of a once hidden middle-America through the scope of the photographic lens. The American family was embracing the photo album with a catholic philistinism, reclaiming Nature as well as the nature of time in a “program of populist transcendence.”[2] It had been that way, says Sontag, ever since the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, when the camera rode the rail West. Like so many of Sontag’s essays on aesthetics—rife with literary comparisons and insistent on bridging the gap between literature and the “craft based arts”—here Sontag stakes photography’s evolution with Whitman: “Nobody would fret about beauty and ugliness, he implies, who was accepting a sufficiently large embrace of the real, of the inclusiveness and vitality of actual American experience.”[3] “The United States,” Whitman offered, “themselves are essentially the greatest poem.” Sontag interprets the work of Walker Evans and Diane Arbus through a similarly optimistic intersection: “All facts, even mean ones, are incandescent in Whitman’s America—that ideal space, made real by history, where ‘as they emit themselves facts are showered with life.’” It was photography’s job to demystify the ordinary lives people already led behind closed doors.

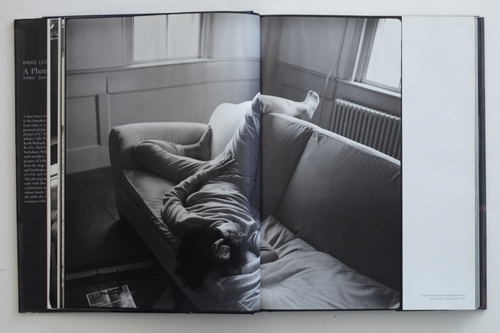

West 24th Street, New York. 1993

(While reading Sontag’s description, I picture an executive from Kodak erecting signs in front of various hangouts in a town in the Midwest, circa 1950. Red pickup trucks. A dog named Dan in front of a diner. A 24-hour store called “Stewart’s,” with a sign in the window advertising a special on Cream Soda and liter bottles of Tab.)

In an article for Artforum after Sontag’s death, Hal Foster said of Sontag’s desire to connect the aesthetic and the moral, “What could be more Arnoldian than her seriousness?”[4] For a moment, I think he is right. Sontag was a great annotator of dangerous ironies. “In the form of a photograph, the explosion of the A-bomb can be used...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in