An Interview with Dolan Morgan

Where did Dolan Morgan come from? The stories in his first collection—just published by Aforementioned Productions—make you wonder. Here, psyches stretch the dimensions of physical space, and the most intense aspects of relationships (yearning, loss, pursuit) are played out on geographies that may feel like game boards. The weather is alive.

Morgan came from Connecticut. He grew up in a family that was both large and miniscule, in a space that was both rich and poor. He got himself out of high school early, and at age seventeen he headed to New York City and never looked back. He became a full time schoolteacher and quit in his twenties when he realized he was looking at the rest of his life. Now he designs curricula, and writes fiction and poetry. Currently, he’s thinking about hijackings as myths, as well as the literary subgenre that features monster sex.

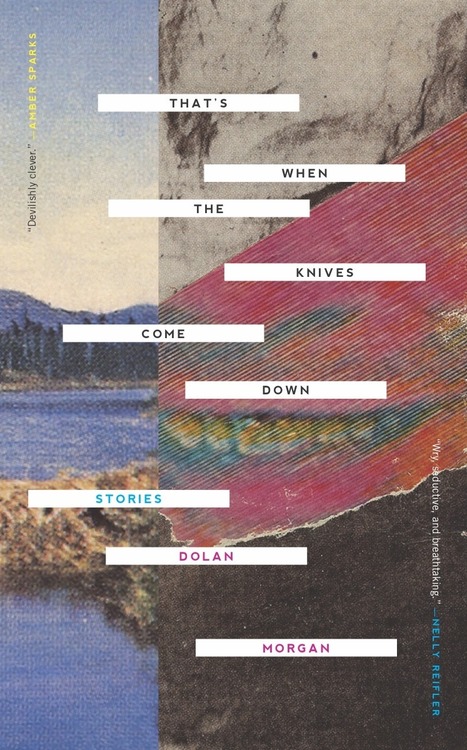

When the Knives Come Down also happens to be the first full-length, one-author work to come from Aforementioned Productions. Since 2005 they’ve been publishing work online, in chapbooks, and in an annual print journal. This is a glorious debut for both parties.

—Nelly Reifler

I. JEFF GOLDBLUM OFTEN FAILS

NELLY REIFLER: So, my first question is about your sense of That’s When the Knives Come Down as a whole. Each story has its own, complete world, and the characters and their experiences feel completely organic within those specific worlds. For me, the contrasts and echoes from story to story make the book and its arc super strong. I’m wondering if you conceived of the stories as pieces of a collection while you were writing them? Did they respond to each other? And if so, how?

DOLAN MORGAN: In some ways, the collection is just a bunch of unrelated stories without any kind of theme tethering them together. No rhyme, no reason. Just one thing after another blindly shouting at you without aim or purpose. But of course that’s not actually possible. I’m willing to admit that I’m a person and I wrote them and I have things I care about and those things shine through whether I write about goats or planets or monsters.

In an earlier iteration of the collection, I intended for all the stories to be linked around a central idea. That idea, taken broadly, was catastrophe, and in particular that everyone secretly wants disaster to happen to them. The original structure was contrived and a bit forced, and I ultimately made a lot of changes to the lineup, but that initial concept still shows up in a lot of places. Characters lust after bad choices, pray for things to go wrong, and gently nudge their lives in the direction of collapse. Likewise, I’m obsessed by good acts being the root of all evil, that somewhere behind every abomination is a series of reasonable decisions made by people trying to do the best they can. There’s that old tale about a beggar who runs into death at the market. Death points at the beggar, inspiring so much fear that the beggar borrows a friend’s horse, rides to the city and hides for the night. The friend, pissed to lose a good horse, asks Death why he scared the beggar like that. Death replies he was merely surprised to see the beggar in the market—because their appointment was for later that night in the city. The end. Anyway, it’s possible that all of my stories are that story, except that the beggar usually knows exactly what’s coming.

NR: It’s true that, in many of these stories, there’s a sense of people desperately (secretly, perhaps unconsciously) wanting to be delivered from the cages of their lives by some powerful and painful outside intervention.

Did you have readers through these different conceptual phases? If so, who was reading the stories and how did you work with them?

DM: For a lot of the stories in That’s When the Knives Come Down, I shared initial drafts with a small group of friends. They’d help locate points of confusion and amusement. I wasn’t interested in deciding if a story was good or bad, but more along the lines of: What happens if I do this? Or this? Or that? Like a science lab. I wanted to gauge effect/impact of specific maneuvers more than quality/value overall. I think this approach stems most likely from my sense of wonder/awe (abject fear?) at the chasm that exists between a person’s brain and the rest of the world. How does anyone manage to say anything to anyone. It’s a lot like Jeff Goldblum trying to teleport things in The Fly. He has two chambers, and he tries to get something in X to travel to Y. You know, like from the inside of my head into anywhere else. And in the movie, like me, Jeff Goldblum often fails. The item in the teleporter won’t translate correctly. Things aren’t received as intended. The steak tastes funny. The monkey dies. That’s how I feel most of the time, and feedback has helped me to know if I’m writing a story or accidentally transforming into a human/insect hybrid.

I’ve also been very lucky to receive fantastic editorial support from magazines that gave my work a home. Ronnie Scott and Sam Cooney of Australia’s The Lifted Brow, for example, took a risk on publishing some of my stories early on—and they were both so gracious and thorough with their edits. I am forever thankful for their approach and dedication and encouragement.

This brings me to a kind of other reader: the imaginary one. When I write, I sometimes call upon internalized versions of previous feedback from people I’ve trusted. I see a sentence or phrase or paragraph or plot development, and then I run a sort of internal app in my head that models how someone might react to it. Little faces appear inside my body to declare their aesthetics. In other words, Ronnie and Sam, if you’re listening: I keep crude, fake versions of you locked away in my mind and only let them out to edit.

II. WHERE PEOPLE END AND THE ENVIRONMENT BEGINS

NR: When I think of your book, I think of geography, topography, and cartography. Can you talk about how you come to imagine (and then go about describing) such complex yet clear locations for your stories? And perhaps you can touch on what place means to you, what it stands for—or stands in for.

DM: It’s true, a lot of my work focuses on place, so much so that people are sort of tossed aside to make room for the environment as a central character. I think, in fact, this happens in every story. Cities replace spouses and birds. Landscapes speak. Organs and architectures intertwine.

At first glance, the reasons for this seem complicated, but maybe they’re not. At one of your recent readings, Nelly, you explained your own hesitation to write anything that could be perceived as even remotely autobiographical. This hesitation runs so deep, you said, that a lot of your work doesn’t have actual people in it (Elect H. Mouse State Judge being a prime example). I have a similar sort of aversion. Inventing and writing about people is not something I find inherently compelling. A lot of people love to “get into a good character” in a book or story, but I’ve never felt this way. When I read, I’m interested in waves of emotion, movement and rhythm, the interweaving of different ideas and structures, and the construction/mimicry of certain concepts and moods. A character, or the development of a persona, can contribute to this and I can enjoy that, but it’s not the main pony in the show.

Sometimes, I’m really concerned about the fact that I invest so much emotional energy into places and objects and patterns at the expense of people. Am I a cold jerk? A sociopath? But I think it actually stems from the fact that I have trouble delineating where people end and where the environment begins. When I look back on emotional connections that I’ve had with other people, our bodies and our feelings bleed into the walls and floors and items around us. The lobby, the living room, the sconces and upholstery. I see identity as a kind of dialysis between mind and environment, with the one sifting in and out of the other. There’s a sentimentality to this, of course—the idea of us leaving traces of ourselves like a sheen on everything we touch, a layer which I don’t want to ignore and hope to give voice to; but there’s also a cynicism, wherein the landscape presides over our moods and choices, so that when we look at an adversary or a friend, their anger or their love is just as much a product of themselves as it is of their electronics and blankets and childhood home. When you see people, you see places/objects, and vice versa. I mean, if a shoe can feel like a person, then I suppose I can too. Why not. It’s me and you, shoe.

NR: The abyss in “Plunge Headlong into the Abyss with Guns Blazing and Legs Tangled”: May I hear about the challenges and pleasures of writing a story in which the central thing is a non-thing? And it’s not the kind of non-thing we usually see in imaginative or speculative fiction. It’s sort of an answer to your typical fiction void. A non-non-thing.

DM: That story exists at the intersection of two trajectories in my work. The first is relatively straightforward: the use of negative space. It happens all over the collection, but especially here. When I was very little, I really loved this weird crocheted item my grandmother had around the house. I liked the way it felt in my hand, but also its deceptiveness. When you looked at it, you just saw a bunch of weird green squares. But then! But then! Suddenly Jesus would appear. In the space around the green blocks. No holograms, just wonderful needlework. It was a miracle of negative space. With the same kind of pleasure this little object gave me, I like to write about things that aren’t there. I like to see the effects of their absence or the impact of that impossibility. I like to discuss what surrounds something as much as what fills it, and to give agency to things that can’t exist. Because things that can’t exist do exist. Things that aren’t there are there. And they don’t get written about enough. I’m happy to pitch in. Let’s make little miracles around all the crap.

The other thing converging on that story is that I’m super tired of the sort of traditional, twentieth-century-style void, where people feel a “dead emptiness inside the brain,” and where they get dizzy and sick at the edge of a life without meaning. Blah, blah, blah. Buncha babies. I simply don’t understand what’s so scary about nothingness. In fact, I find it uplifting and invigorating. It makes me happy. And I feel like throughout my life, I’ve always been handed an artificial set of social choices: either 1) “Things are absurd and that’s terrible,” or 2) “Things are imbued with purpose, and that’s fantastic.” But really, what about: Things are absurd, and that’s great? And how about: Purpose is terrifying. Purpose is oppressive. Get that junk out of here.

Rather, we’re all flying through a pointless expanse and that’s amazing. Lucky us. Our ability to comprehend the world is imperfect, limited and often incorrect—and that’s gorgeous. We are unimportant, soon to be forgotten, and miniscule; our lives barely register in proportion to the time and space that stretches out around us—and that’s a gift. It helps me care more deeply for the people in my life and struggle harder to get things done. With some joy to boot. So in this story I try to treat the abyss like a piñata. I try to make it colorful and fun. None of that maudlin crap. A papier-mâché donkey. And then I smack it again and again with a little stick to see what kind of candies I can get. I want that mawkish, tired notion of nothingness to play itself out, foolishly, and I hope to approach somewhere new by the end. A place where we can stuff our faces with nothing candies. Then, with mouths full of pointless sweets, we can start talking about what’s truly fucked about the world.

III. FAILED ATTEMPTS

NR: I often feel irrationally crestfallen when someone tells me what their favorite of my stories is (while also of course, being wildly grateful that they have bothered to read anything). I have this maternal response—like the other little ducks are being passed over. So I hesitate to speak about my favorite story in the collection. But I must, because “Nuée Ardente” is simply one of the greatest stories of the new century. It’s eerie, heartbreaking, terrifying—I can’t read it without having a powerful physical response. Like the abyss, this apocalypse isn’t something we’ve seen before: it’s far more subtle, a presence we can’t put our fingers on. How did this story begin? What were its origins? Where do you see its center of balance?

DM: You’ll forgive me, I hope, if I struggle to make myself clear here. That story was an attempt to navigate something that I myself really don’t understand and which makes me a bit uncomfortable. But I think I can carve something out. I moved to New York City in late August, 2001. Right away, I made new friends that I’m still close with today. Life in the city that year took an unexpected turn. As I remember it, there was a wardrobe that we discovered, through which you could walk forever. We passed into it and found an overcast landscape, lit only by a single streetlamp amid the snow. But wasn’t it early September? Still summer? Why should it be snowing? We played duck/duck/goose in the empty streets while a military convoy passed. Movie theaters were free. I stood at St. Vincent’s hospital, volunteering to feed doctors who expected long hours, but no patients arrived, and in fact the hours weren’t long at all, but short. A satyr took us by the hand and we were adolescents even if we weren’t. Bodegas gave free water. The end of the world came and went. It was here and then it was gone. Just like that. In the years that followed, I felt so disgusted with myself to miss it, to think on it with a kind of fondness. To wonder where it went, why it left. It’s a potentially unexplainable feeling. An ugly, but ultimately human, feeling. Some great massive otherness dropped down on the world like a blanket of unknown snow and then it was gone and I longed for it. It doesn’t matter what it really was—because for a moment it was anything. The breach of routine was so extreme as to render magic real, if only briefly. Lions talked. And it’s hard not to miss magic once it leaves, I suppose is all I can say, and that can be a despicable thing because magic expresses itself through real tragedy. I’ve only very rarely discussed this repulsive desire, but that’s what the story pivots around. Perhaps my obsession with architecture and negative space is more easily explained than I let on. I saw this same pattern spreading out into other parts of my life, and in the obsessions of the people around me, and I knew I needed to work through it in writing.

NR: Finally, I’m terribly curious: what writers did you grow up reading? And what books (or music or movies) impressed themselves on this collection the most?

DM: When I was a little kid in elementary school, my sisters begrudgingly babysat me. They were much older and would drag me along for long car rides as they went about their teenage adventures, smoking and laughing and careening through forested nights in a rundown Ford Escort. On a constant loop, they played Metallica and Ace of Base. Loudly. And they sang along, yelling out the windows. Something about the intersection of those cheesy dance songs and the raucous metal, plus the summer air and endless roads, being dragged along against our will—I think that’s an early influence on my work. I see an enormous orange block of generic American cheese wasting away in the fridge.

At that time, too, I would read just about anything I could get my hands on. I stole books constantly. From stores, from libraries. I believe all children should be taught to steal books, as a public service. I read so much that my eyes would burn. So I’d lick my fingers and rub saliva around my eyelids to lubricate them in order to continue. This caused my eyes to become caked in dirt, so I started keeping a bowl of warm water near me with a washcloth, which I would dab on my eyes at the turn of every page. Great system. Very cooling. This helped me get through the body of work of my elementary school obsession: Michael Crichton. Jurassic Park! Sphere! The Andromeda Strain! These books absolutely blew my little mind.

And in my teens, I used to meet some friends at the tiny, local drycleaner. We would sit in the old display window, write and talk about literature in between visits from customers dropping off coats and shirts. There, I became obsessed by Ionesco, especially “The Bald Soprano.” Dadaists were my foolish teenage crush. I stole a copy of Nathanael West’s complete works and have never let it go. The range from A Cool Million to The Dream Life of Balso Snell to The Day of the Locusts is insane. I thought the world had made a mistake. Joan Didion beat the shit out of me with landscapes. Later, I fell hard for that kind of standard boy’s club of writers: Calvino, Saunders, Keret, Ballard, Borges, Bolaño, DeLillo. Today, I think my biggest literary influences are robocalls from telemarketing scams. As for music, it’s fair to say that all of the stories in this collection are failed attempts to finish Mahler’s 10th symphony.