“IT WILL KILL YOU, AND IT NEVER KNEW YOUR NAME.”

An Interview with Karen Russell About Her Syllabus

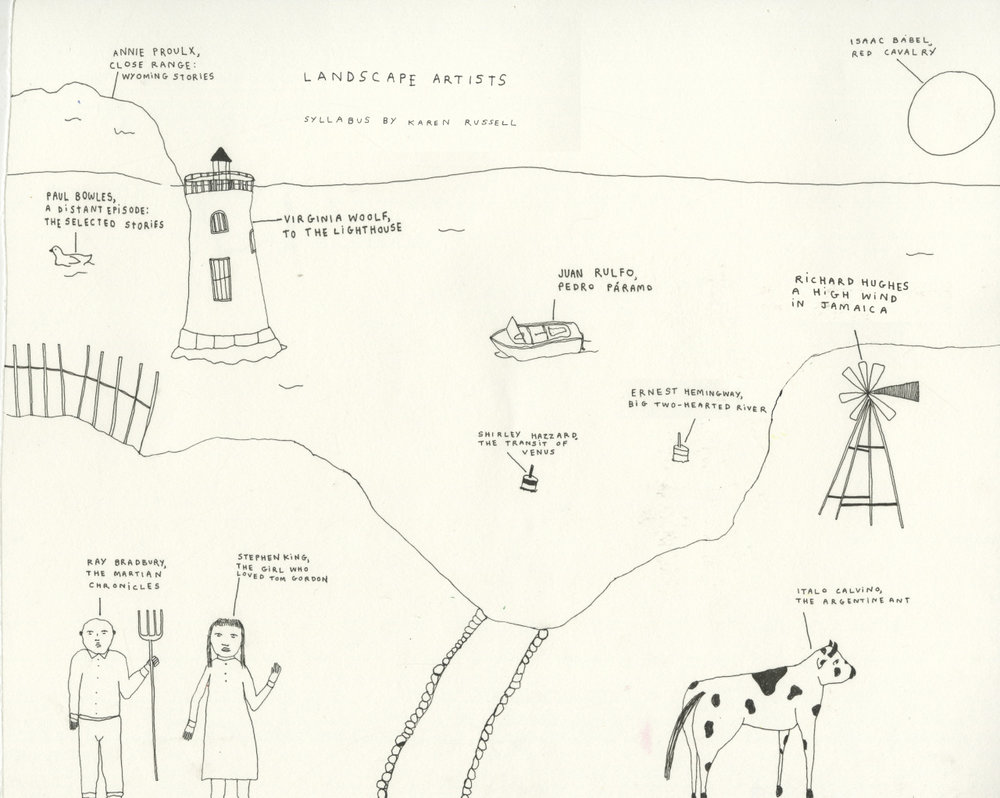

This is part of a series of conversations with writers who teach, where we discuss how they develop an idea for a course, generate a syllabus, and conduct a class. See the full syllabus here.

Karen Russell is the author of the novel Swamplandia!, a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize. She is also the author of two short story collections, Vampires in the Lemon Grove and St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, and a novella, Sleep Donation. Russell is the recipient of a 2013 MacArthur Fellowship, and she has taught at Columbia University, Bard College, and Bryn Mawr College.

—Stephanie Palumbo

I. THE SPOTS ON THE LITERARY TRAM TOUR

SP: Where did you teach this class?

KR: At the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I should tell you I’m a little bit self-conscious, because I’d never taught this class before and was afraid I had the reek of fraudulence upon me.

SP: I think most teachers feel that way.

KR: Yeah… We’ve been duped, right? [Laughs] But actually, I had a class with Bill Savage at Northwestern, on female writers of the Beat Generation like Djuna Barnes—folks that I’d never read, and he hadn’t read them either. He was upfront about it: he would teach books he wanted to read, and we’d all be co-equals. I thought of him when I was teaching at Iowa, because I’d read and loved the books on my syllabus, but I’d never taught them before.

SP: How did you choose the theme of landscape stories for your syllabus?

KR: It’s interesting—some writers start with character, but I almost always start with place. If I don’t have a three-dimensional sense of the story’s setting—if I can’t see it in my mind’s eye—I can’t even attempt to make the story come to life. If you ask me about books I love, like Rule of the Bone by Russell Banks or Anna Karenina, it’s the setting, and the sense memory of moving through the landscape of the book, that stays with me far longer than names of characters or details of plot. So I was thinking, what makes a world immersive? What makes a place a character? I realized you could teach any book under that rubric—even something by Beckett, that’s asserting it’s nowhere, definitely has its own atmosphere—so I tried to limit myself to stories set in places you can visit on the map. But I also taught Pedro Páramo, which takes place in the Mexican underworld, and they don’t have Delta flights there. [Laughs]

SP: You mentioned that this was a Sadie Hawkins class. What does that mean?

KR: I thought it would be fun if, at the end of the class, the students chose the stories we discussed. I wanted to know what these crazy smart readers found gratifying. So we had a You Pick ‘Em Day.

SP: Which stories did the students choose?

KR: “Big Two-Hearted River,” for one. In class, we take a sort of field trip of the mind together, and it’s fun to see some of the places we’ve all been to before with fresh eyes—Nathaniel Hawthorne territory, Faulkner’s county, Shirley Jackson’s terrifying “Lottery” village. The spots on the literary tram tour. I assumed Hemingway was on that itinerary, so I handed out the story without his name, but half the class wasn’t familiar with it. It reads totally differently if you remove it from the context of Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories and the war, so it became an accidental experiment to learn how much context informs your experience of a place in story. The students still loved it, but what they loved about it seemed more experiential—the animal happiness of being safe in a tent, for instance.

SP: I could easily identify the landscape in that story, but I had a harder time defining the landscape in The Transit of Venus.

KR: The Transit of Venus might be the most ambitious landscape blend we read Shirley Hazzard moves you from Australia to England to South America to America in different time periods, and it feels like the real setting for these sisters in states of dislocation is the in-between. There’s something arbitrary about the way different wars, revolutionary movements, and cultural shifts buffet these characters’ lives,and yet Hazzard seems to be building a vision of destiny.

SP: The language of the book is also quite striking.

KR: When I’m writing, I always drift into the voice of a first-person adolescent—low to the ground, with a myopic filter. It seems ambitious to take on more than that. But Hazzard writes about six different protagonists with this beautiful, symphonic omniscience. There’s an exciting dissonance between the old school aesthetics of Transit and the politics of the book. In class, we talked about the way that institutions and cultural structures shape the characters’ personalities and generate plot—what’s possible and impossible in different climates, what characters are starving for in America versus London, how ubiquitous a real person can become in her absence, that ghost sprawling across minds and continents, and how that empty space develops its own strange weather.

SP: Hazzard never exactly writes the novel’s ending—she lets the reader piece it together instead. Do you think that makes the book more engaging?

KR: I do. She sets the ending up in advance, so you want to go back to the beginning and admire what she built. Something’s conjugated in the beginning, but you’re still shocked when it happens. It’s sly, but not gimmicky. And the book is still amazingly suspenseful. There’s a kind of glorious doom in the air that feels almost Grecian, this old school prophecy that will be fulfilled. It’s funny—I think part of the reason it resonates is that it’s everyone’s situation, you know? Everyone is learning to acknowledge that it’s unbelievable yet true that their story’s going to end.

II. DARK FAIRY TALES

SP: Speaking of doomed creatures, you teach Paul Bowles’ stories.

KR: I was attracted to Bowles’ stories because he’s working on a cultural periphery, writing landscapes analogous to madness and disillusion. When he was a child, he had abusive parents and terrible illnesses, and he described his fevers like some kind of psychic refuge. He wrote that he could retreat into these feverish states, where his parents couldn’t hurt him and he felt most defended. We talked about that in class—madness as a physical refuge, as a strange sanctuary or private stronghold. So he described illness and fever in his landscapes, using natural terms. He was so good at using a shaky silhouette of a man walking out into the desert to reveal how fragile identity is, how contingent it is on things like weather. He writes about social climbers trying to firm up their egos, but by the end, men are evaporating into the sky. Whatever made them idiosyncratic doesn’t last for long. They wind up emaciated in the Sahara, less and less coherent, the sun eating them in bites.

SP: His tone is pretty matter of fact.

KR: Absolutely. Doesn’t it feel like these stories are as close to human ventriloquy of the voice of the Sahara as we’re going to get? We want to anthropomorphize mother nature, and Bowles exposes the fallacy of that very human desire in these stories—it becomes immediately clear that the Sahara isn’t any kind of mother. Bowles also includes humor and compassion in his work, so it’s not just like, the chilly gaze of the golden serpent’s eye, revealing man’s weakness, or whatever. But his humor is pretty dark.

SP: I feel like there’s an implicit condemnation of colonialism in his stories. Another author might have written racist characterizations of Middle Eastern people, but Bowles makes the Westerners responsible for their own undoing.

KR: That surprised me, because if you paraphrase the descriptions, it sounds like he fetishizes these cultures, like the worst kind of Orientalist, with lyric descriptions of hashish smoke and camels and sunsets. But it really is the opposite—you just see Western hubris. You feel a sense of schadenfreude watching the professor, who thinks he has a strong friendship with a shopkeeper and feels confident in his Arabic language skills, wind up enslaved several paragraphs later.

SP: And tongueless!

KR: You couldn’t accuse him of being melodramatic, even though if someone told me they were writing a story about a linguist whose tongue was cut out by the Reguibat tribe in the desert, I’d feel apprehension on their behalf. It feels like a dark fairy tale, and Bowles uses tone to control our expectations. He gives the protagonist a sketchy, archetypal feel by calling him “The Professor,” with no name or history appended to make him any more distinct to the reader. He’s just a floating skin.

SP: The Italo Calvino story “The Argentine Ant” also feels like a fable.

KR: It’s another story that’s both absurd and horrifying. There’s this unstoppable multiplication of ants, and humans have different theories and explanations that arise like mist in the ants’ wake. It reminds me of the Steven Millhauser story “Invasion from Outer Space,” where pollen starts falling from the sky and doesn’t stop. You cycle through the actions of people—denial, grief, rage. Everyone’s saying, This isn’t dignified, just some goddamn pollen. It’s smart way to wake us up to something horrifying that we’re mostly inured to: that time is multiplying like cancer in a body. What do you do with the foreknowledge of death, and the outrage, the helplessness that follow?That’s such a good question to leave the reader with.

SP: At the end of the story, the landscape changes when the characters leave the ant hellscape and go down to the sea. What does that shift in setting produce?

KR: It’s nice to have that breath to appreciate the horror of the ants, and it’s scary to understand that the ant-ridden village has become the characters’ home now. It gives us a sense of place, of “home” versus “away.”Sometimes I think about it like Kansas and Oz—the way that utopias have to exist in relation to the real world. In class, we all had wildly different interpretations of that ending, which ultimately probably revealed more about our own anxious hopes than about the Calvino story itself. Some students thought the beautiful white shells at the bottom of the sea were a Christian allegory or arrow to the divine. I guess I was a more literal-minded reader. It’s bones! (Laughs) Yup, we’re gonna have to deal with a lot of crawling sensations, a plague of ants, and we’ll only be relieved when we die. It’s a terrible privilege to be attacked by ants for the duration of your life on this planet.

SP: Annie Proulx is on your syllabus, and she also writes about landscapes that seem uninhabitable or unrelenting.

KR: Most people think of her as a realist even though she writes with hallucinatory detail and makes things vibrate so intensely that they feel surreal and magical. She’s faithful to jargon— cowboy slang, names of tractors, the brand of cattle—and getting those details right gives her permission for her flights, like a talking tractor or half-skinned steer. The talking tractor story, “The Bunchgrass Edge of the World,” opens with the line, “The country appeared…” The country is the character. Humans wander onto the scene for a little while, their dramas are foregrounded, and then they fall away again, and we’re back to cycling through the seasons. It’s an Alice in Wonderland resizing of priority. I don’t know many stories that are able to represent and take seriously human drama while also underscoring how fleeting and ultimately insignificant human life looks against a backdrop of the geological time that dwarfs us. It’s poignant to try to tell a family story underneath the terrifyingly vast Wyoming sky.

It’s weird—we think of nature as fragile, something we’ve destroyed, that we’re these parasites on the planet and have all but obliterated certain ecosystems, but reading her stories, you also feel that, nope, nature is resilient, sublime. It will kill you, and it never knew your name. The annihilating blue of the sky, the fatal snows. If you think you can plead your special case against that blue, good luck. It’s unsettling to read Annie, in a good way—you’re forced to contend with your own fragility.

III. BRADBURY’S BASTARD CHILDREN

SP: The humans in The Martian Chronicles are facing their own limitations as well—except they’re doing so in an alien landscape.

KR: Like the desert, Mars is hostile to human life. So to set a story there is automatically suspenseful—the landscape transforms the humans into aliens, and there’s this sense that every footstep is a violation of some primordial taboo. It’s clear that they don’t belong there. The book feels subversive to me as an adult reader.I know most people encountered the book in middle school, but the language is beautiful, shot through with this unique imagination. Ray Bradbury is part of the reading history of every writer I know. Really, we’re all Bradbury’s bastard children—he clearly sired everybody’s imagination.

SP: How does Bradbury use human activity on Mars as a metaphor?

KR: He’s writing against patriotism during the Cold War. Humans land on Mars and then destroy it. Not much time elapses between landfall on Mars and the annihilation of all Martians.

SP: There’s a haunting image in one story, where a little boy is playing with a white xylophone that turns out to be a Martian ribcage.

KR: The planet is basically wiped clean of its indigenous people. I was shocked by the descriptions of these ancient, bone-white cities on Mars, and it took me an embarrassing length of time to recollect that people can visit ruins anywhere on our planet, too. It’s a case where sci-fi holds up a funhouse mirror to our own history. In case we have amnesia about the horror of the frontier, here we see another frontier and xenophobia, paranoia, aggression, madness. But we see people be really good to each other too. Bradbury seemed to be such a humanist at the same time that he is calling us out on our most despicable qualities.

SP: One of the best stories in the collection, “There Will Come Soft Rains,” isn’t set on Mars. It takes place on earth, in this automated robot house that continues to function after the family who lives in it dies.

KR: Oh, I love that one so much. It’s a haunted house story, really. Haunted by the absence of people. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, the sprinklers come on. Even in its death throes, the house is still obeying its old programming. Without the house’s occupants to block our view, we can see how they once lived, and those formerly banal rhythms—the things you’re inured to on an average Tuesday—seem precious all of a sudden, and totally weird, too.What comes to light if you evacuate a space of people? I had the class write a ventriloquy of an empty space—students wrote about movie theatres, a sunken galleon, an ice skating rink. They’re all ghost stories in some way.

SP: I love that the theme of your syllabus isn’t really landscape stories. They’re all stories about death.

KR: Oh yeah, let’s talk about what we’re really talking about. There’s a section in To the Lighthouse called “Time Passes” where there are no human characters. Things fall of shelves, teacups detonate, shadows move around. It’s a novel way to talk about the monstrous loss of World War I, a slow violence that can’t be dramatized on the news. How are you going to make the erosion caused by time passing interesting and dramatic to a reader?

SP: The film Boyhood addresses time in a similar way. The most mundane details of your life are elevated to this almost sacred place when you see how quickly time passes. Except there are people in the film, unlike Juan Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo, which takes place in a literal ghost town.

KR: I was surprised to learn Rulfo revised the book for ten years, because it feels like it must have emerged from him as a seamless bubble, written in a trance-like state.

SP: How do you help the students through it?

KR: The prose generates momentum and just sort of rolls you under, so you can surrender to the spell of the book. When you’re descending into this valley in the story, Rulfo gives you permission to be strait-jacketed into the strange logic of the story, along with the protagonist.

SP: How does he evoke that feeling?

KR: I think through the absence of objections. You might expect someone following a corpse into a valley to be like, Hey! You’re dead! How can you explain that one to me, pal? I’d prefer not to follow you into this underworld! But in fact, at no point do these characters object to even the most harrowing and illogical events in Comala, and their surrender makes the book all the more terrifying. They are prisoners, trapped in a true nightmare. And reading along, I often felt that I was similarly powerless to object to anything that might happen in Rulfo’s netherworld. Do you know that feeling from dreams? You’re aware of danger breathing down your neck, but it doesn’t seem like you have the right muscles to flee. You’re volitionless.

SP: Like Bowles and Bradbury, Rulfo addresses political and social injustice. How did you cover that in class?

KR: We talked about the feudal system he described—the way the power was structured, the way the women had zero autonomy in that economy, the way everyone was under the thumb of their don—and how that passive kind of violence felt congruous with the stupefaction that pervades every page of this book, the futility of trying to alter the horror in progress, the dream-paralysis. And we talked about the structural repetition of some scenes, the way these sleepwalkers couldn’t free themselves from the cycles of violence. Several students suggested that Páramo functions as a geopolitical critique of the way certain power structures can roll people under and hold them hostage, apparently for all time.

SP: You could apply that to other places haunted by economic inequality, like Detroit.

KR: Absolutely. There are many cities in America that feel moated by poverty, where time seems to have looped back in on itself.

SP: This book must have generated such interesting discussions. I wish I could have been a student in your class!

KR: I miss being a student so much too. That was part of the pleasure of teaching a course like this, especially at Iowa. It’s rare to go on voyages with other readers. I loved knowing that, over the weekend, everyone was tandem hang-gliding through Australia or the underworld, and we were going to group back up on Monday to discuss it.

Illustration by Josephine Demme.

Stephanie Palumbo is a documentary film and television producer, and a former assistant editor at O, the Oprah Magazine. She lives in Brooklyn with her boyfriend and cat. You can follow her @onetoughnun.