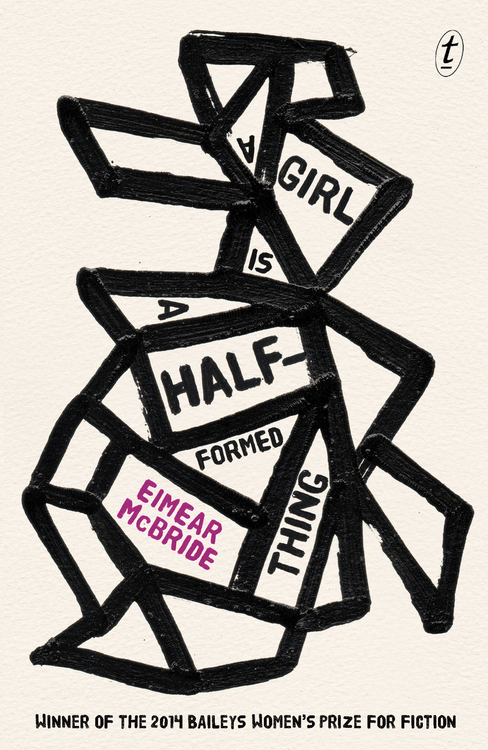

If you read Eimear McBride’s debut novel, A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing, over a short period of time—a weekend, say, or a sleepless night—you might begin to have the distinct feeling that some noisily expelled Sibyl has commandeered the schoolhouse. She dismisses the rules as absurd. She regards good behavior with disdain. In a deluge of words that rail against every make-believe protocol for existing that teachers have ever taught her, she lays bare all she’s been asked to keep quiet, every slip in her sense of self-preservation. She collars you and she works at you with a fundamentalist’s persistence.

Consider, for instance, that she insists everything real—realism, reality, the attitude of being “realistic”—is a kind of blasphemy. And she draws you into your own mostly secret apostasy. That is, she wants you to consider a world of bad influence which is chaotic, yes, and darker, absolutely, but beautiful, richer. Worth the trouble. She spells out the question and answers it for you: “What if. I could. I could make. A whole other world a whole civilization in this this city that is not home? The heresy of it. But I can. And I can choose this. Shafts of sun. Life that is this. And I can.”

ACTS OF DEFIANCE

For the best part of the year that I was fourteen I walked home from school reading, often barefoot. The school mandated that we, all girls, wear a uniform of straw hats and boxy blue dresses. And everything about it—up to and including the lip-glossy, deodorant, clean hair smells of the other girls—created the sensation of being slowly caught in the amber of a world all composure, checked impulses and neat fingernails. A world that I had absolutely no interest in inhabiting. So once I had boarded the train in the afternoons and travelled the four stops down the line, I’d find a vacant bench. I would take a book out of my bag and replace it with my shoes, scrunch my school hat into a ball, untie my hair and let it fall well past my shoulders. I proceeded to walk the twenty minutes home from the station dodging glass, gumnuts and used syringes, looking up from the pages exclusively for traffic lights. It was just about my only real act of teenage defiance. I was too obedient to rebel in any serious way against school or my parents, although I wasn’t, at the time, crazy about either. I wasn’t the kind of teenage girl who climbed out bedroom windows and shimmied down drainpipes. Although something that felt similarly subversive was happening in my mind.

Fourteen was the age that I made a ritual of walking home...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in