Go Forth is a series curated by Nicolle Elizabeth and Brandon Hobson that offers a look into the publishing industry and contemporary small-press literature. See more of the series.

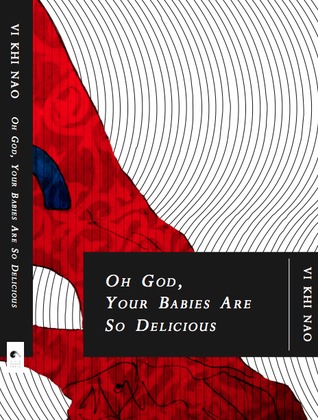

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Swans in Half Mourning, The Vanishing Point of Desire, and Oh, God, Your Babies are So Delicious. Her fiction has appeared in such journals as NOON, Ploughshares, and Glimmer Train. She received an MFA in literary arts from Brown University.

—Brandon Hobson

BRANDON HOBSON: In terms of style, some of the stories in Oh, God, Your Babies are So Delicious are very different from others. More specifically, some are much more experimental. “Colon” and “The Lesbian of Dry Cement,” for example, are numbered, terse, much different than “Cucumber” or “The Divorce”. Then there are the stories that balance between poetry and prose: the one sentence "The Problem with Literature Today" or “The Kiss.” Were these stories written over a period of time when you were experimenting with different styles, or is this change specific to this book?

VI KHI NAO: These stories, exactly thirty-four stories (to match the age of my existence), were written over the course of nine years. The story “Cucumber” was written a year ago. What do you mean by traditional?

BH: I guess in terms of storytelling, less experimental.

VKN: I think the only story that comes close to being traditional is “Tom is Handsome.” The rest float up like a distant cloud of pleasure and latexed-humor (you can only laugh if you are wearing sanitary gloves). “Colon” is numbered because the narrative is defined through the architecture of dictionary and the rhetoric of its etymology. “The Lesbian of Dry Cement” rests its spine on the sexuality of arithmetic, which controls the education of the children in the story. For some reason, I have always linked numbers to documentation and numbers to children because in the past, you had to line the children up like stairs to count them. This is a non sequitur: in Vietnamese, if you are the third child in the family, you are named Child Three. Sometimes children have to behave like calendars to mark the years for their aging parents.

BH: One of the things I love about this collection is your titles. Can you talk a little about how you came up with such fantastic titles?

VKN: The titles are born out of the voices of the writing. Sometimes a sentence would appear in my head at the beginning of writing a piece and that sentence wouldn’t leave me alone until I wrote it down. As soon as I write it down, the words march...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in